Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on April 12, 2004

Transcript

DATE April 12, 2004 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

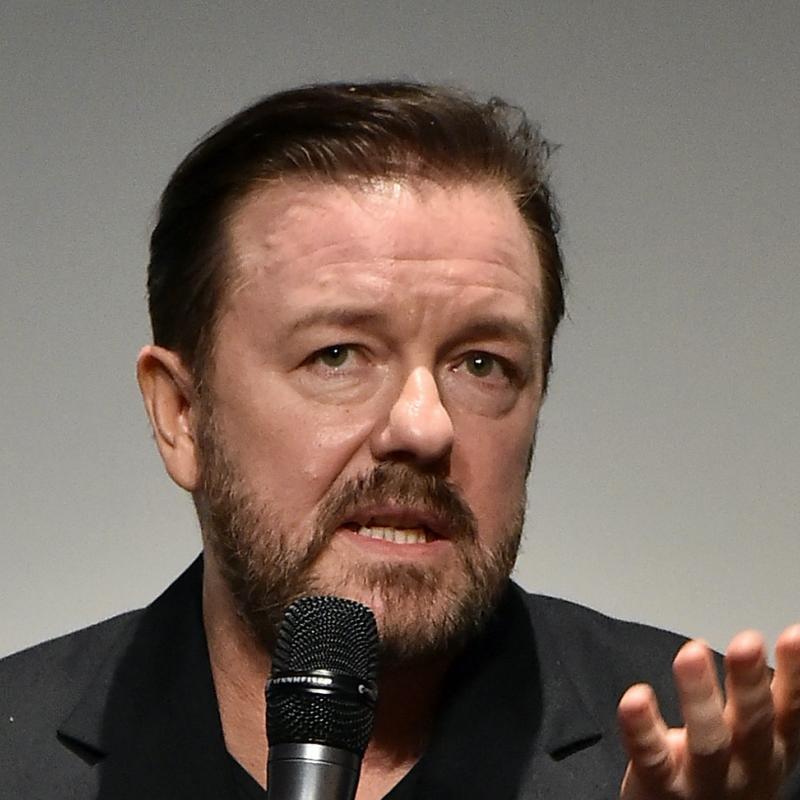

Interview: Ricky Gervais discusses his show, "The Office"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Ricky Gervais, is the co-creator and star of the hilarious sitcom

"The Office." Gervais plays David Brent, a mid-level office manager in a

small branch of a paper company who thinks he is hip, funny, smart, a wise

philosopher and a good friend to his staff. Unfortunately, he is none of

those things. He is too self-absorbed to notice that his staff constantly

winces as he holds forth. Entertainment Weekly called the character `the most

brilliantly clueless boss on the planet.' Gervais won a Golden Globe this

year for best actor in a TV comedy, and the series won for best comedy. It

also won a Peabody. The show is programmed on BBC America Thursday nights and

is out on DVD. Here's a scene in which Gervais, as office manager David

Brent, is discussing a performance evaluation form with his receptionist,

Dawn.

(Soundbite of "The Office")

Mr. RICKY GERVAIS (Actor): (As David Brent) If you had to name a role model,

someone who's influenced you, who'd it be?

Ms. LUCY DAVIS: (As Dawn) What, like a historical person?

Mr. GERVAIS: No, somebody in sort of general life.

Ms. DAVIS: Oh.

Mr. GERVAIS: Just someone who's been an influence on you.

Ms. DAVIS: I suppose my mum. She's just--she's strong, calm in the face of

adversity. Oh God, I remember when she had her hysterectomy.

Mr. GERVAIS: If it wasn't your mother, though. I mean, it doesn't even have

to be a woman. It could be a, you know...

Ms. DAVIS: Man.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

Ms. DAVIS: OK. Well, I suppose if it was a man, it would be my father.

Mr. GERVAIS: Not your father. I mean...

Ms. DAVIS: No?

Mr. GERVAIS: ...let's paint your parents as red. I'm looking for someone in

the work-related arena who's influenced...

Ms. DAVIS: Right. OK. Well, I suppose Tim then. He's always...

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, he's a friend, isn't he? Not a friend. Somebody in

authority, I mean, you know...

Ms. DAVIS: Well, then I suppose Jennifer.

Mr. GERVAIS: I thought we said not a woman, didn't we, or am I...

Ms. DAVIS: OK. Well, I suppose you're the only one who...

Mr. GERVAIS: Oh. Embarrassing. This backfired, didn't it? Oh, dear. Very

flattering. Can we put me as a...

Ms. DAVIS: OK, Tim then.

Mr. GERVAIS: We said not Tim. So do you want to put me or not?

Ms. DAVIS: OK.

Mr. GERVAIS: Right. So should I put strong-willed ...(unintelligible)?

Ms. DAVIS: OK.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: I love the distance between what the character thinks of himself and

what he's really like and...

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, the blind spot is one of my favorite things. I mean, in

life and comedy, I think it's funny and it's tragic, the way he talks about

everyone loving him, that's a strange thing to say. To wear your popularity

on your sleeve. He's one of those people that would rather hand out sort of

business cards than bother getting to know people. He wants to say, `David

Brent, great bloke, you'll love me, I'll like you in return.' Pretension is

always interesting. I love pretension. Vanity. Vanity might be my favorite.

So you put that in a man, and you put it in a 40-year-old man, and you put it

in a 40-year-old man who thinks he's the funniest, most popular man in the

world, and you can't go wrong really.

GROSS: Some of my favorite shots in "The Office" are the cutaways to the

people who work in the office, and every time David Brent is like telling a

joke or describing what a great boss he is or, you know, how funny he is,

everybody's like averting their eyes and looking at their shoes or staring at

the wall or just, like...

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, that--well, yeah, comedy's...

GROSS: They're so...

Mr. GERVAIS: Comedy's contextual. I mean, the funniest thing in the office

aren't the people who are actually funny. They're the people who aren't

funny. It's the faux pas. It's the failure that's amusing. I learned a lot

from Laurel and Hardy. The funny thing wasn't Stan saying something stupid.

It was the cut to Ollie, who then looked at him like he was the worst person

in the world, and then he looked at us, as if to say, `Why am I with this

idiot?' When Brent tells a bad joke, it's the fact that it goes to other

people not laughing.

GROSS: But you've created this story about life in an office. Have you ever

worked in an office?

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: You did?

Mr. GERVAIS: I worked in an office for eight years. That's where I got it

all from. I was a middle manager. I went to management training seminars

where they speak as--talk rubbish for two days. Yeah, I worked in an office

for seven or eight years.

GROSS: What kind of office was it?

Mr. GERVAIS: The office in the series is based on the office I worked in. We

actually shot the demo in my old office, that very generic open plan thing. I

worked around reception for a while, then I was a publicity officer, then I

was assistant events manager, then I was events manager for about five years.

So it was all going in.

GROSS: So where was this?

Mr. GERVAIS: This was the University of London Union in London.

GROSS: Are any of the story lines in "The Office" based on things that have

happened to you?

Mr. GERVAIS: Oh, let me think. Let's see. Well, the episode four in series

one where we had the guy come in to train people, I remember the first

training session I went to, it was held by some other managers when I was

just, I think, on reception, and they weren't really trained for it, and I

remember they did role playing, and I remember the time thinking, `This is

ridiculous,' because they sort of divvied it up between them and said, `OK,

I'm gonna play a bad hotel manager. You play the customer.' And it started

off, `I'd like to complain about my room.' `Well, I don't care.' `Well, you

should. You're the manager.' `Well, go to another hotel then.' `Well, I

will.' And they went, `That's the wrong way to do it.' And then they said,

`OK, now we do it the right way to do it.' And he comes in and says, `I'd

like to complain about my room.' `Oh, I'm very sorry, sir. What's up with

it?' `Oh, it's just dirty.' `Oh, well, I'll have someone clean it and you

can have it for free.' Brilliant. It was like as black and white as that,

and I remember thinking, `I don't know what the moral is.' So I quite like

spoofing role-playing.

GROSS: Why don't we hear that scene? And in this scene, David Brent is

role-playing with the guy who's running the seminar, and David Brent is

supposed to be playing the customer, and the guy running the seminar is the

hotel clerk.

(Soundbite from "The Office")

Mr. GERVAIS: (As David Brent) I'd like to make a complaint, please.

Mr. VINCENT FRANKLIN: Don't care.

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, I am staying in the hotel, so...

Mr. FRANKLIN: I don't care. It's not my shift.

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, you're an ambassador for the hotel.

Mr. FRANKLIN: I don't care. I don't care what you say.

Mr. GERVAIS: I think you'll care when I tell you what the complaint is.

Mr. FRANKLIN: I don't care.

Mr. GERVAIS: I think there's been a rape up there! I got his attention. Get

their attention. OK?

Mr. FRANKLIN: Right, so there were some interesting points...

Mr. GERVAIS: Very interesting points.

Mr. FRANKLIN: ...(unintelligible) up there. It's not...

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

Mr. FRANKLIN: ...quite the point I was trying to make, David.

Mr. GERVAIS: Different points to be made. OK?

Mr. FRANKLIN: I'm more interested, really, in customer care...

Mr. GERVAIS: So am I.

Mr. FRANKLIN: ...and the way that we would deal with somebody that...

Mr. GERVAIS: I phased--maybe I should--as I thought, I should play the hotel

manager, 'cause I'm used to that. I phased you. But you have a go. See if

you can phase me. OK?

Mr. FRANKLIN: Yeah, all right.

Mr. GERVAIS: OK?

Mr. FRANKLIN: Hello. I wish to make a complaint.

Mr. GERVAIS: Not interested.

Mr. FRANKLIN: My room is an absolute disgrace.

Mr. GERVAIS: Don't care.

Mr. FRANKLIN: Look, the bathroom doesn't appear to have been cleaned and

it...

Mr. GERVAIS: What room are you in?

Mr. FRANKLIN: Three six two.

Mr. GERVAIS: There is no 362 in this hotel. Sometimes the complaints will be

false. OK? Good.

GROSS: David completely misses the point in that, but that's so typical of

him.

Mr. GERVAIS: Of course, because he wants to be top dog. He wants to be the

center of attention. He couldn't--you know, he hires this guy, but then he

wants to be in charge, so he's just a child, you know. It's his football, and

he's got to be, you know, the most important player.

GROSS: Now later in this same seminar, David turns the discussion into

basically a Q&A about himself, and then...

Mr. GERVAIS: Yes.

GROSS: ...he reveals he used to be in a band and then he takes out his guitar

and he starts playing some songs.

Mr. GERVAIS: Awful.

GROSS: Awful. In fact, let me play some of the song.

(Soundbite of "The Office"; music)

Mr. GERVAIS: (Singing as David Brent) Spacemen came down to answer some

things. The world gathered round, from paupers to kings. I'll answer your

questions, I'll answer them true. I'll show you the way. You know what to

do. Who is wrong and who is right? Yellow, brown, black or white? Spaceman,

he answered, you no longer mind. I've opened your eyes. You're now

color-blind.

Racial. So...

(Singing) She's the serpent, who guards the gates of hell. Yeah.

(Soundbite of applause; guitar)

Mr. GERVAIS: (Singing) Pretty girl on the hood of a Cadillac, yeah. She's

broken down on Freeway 9. I take a look and her engine started and leave her

purring and I role on by. Bye-bye. Free love on the free love freeway...

Unidentified Man #1: That's what it is.

Mr. GERVAIS: (Singing) ...and love is free and the freeway is long. I got

some hot love on the hot love highway. Ain't going home 'cause my baby's

gone.

Unidentified Man #2: (Singing) She's dead.

Mr. GERVAIS: She's not dead. (Singing) Long time later see a cowboy crying.

He says, `Hey buddy, what can I do?' Says, `I lived a good life. I've had

about a thousand women.' I said, `So why the tears?' He says, `'Cause none

of them was you.'

Unidentified Man #3: What, you?

Mr. GERVAIS: No, he's looking at a photograph.

Unidentified Man #3: Of you?

Mr. GERVAIS: No, of his girlfriend. The video would have shown it.

Unidentified Man #3: Sorry.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

Unidentified Man #3: He sounds a bit gay at the moment.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. GERVAIS: (Singing) Free love on the free love freeway. The love is free

and the freeway's long.

GROSS: That's Ricky Gervais as David Brent in a scene from the British sitcom

"The Office," which is on BBC America, and is also now on DVD.

Now, Ricky, I know you used to be in a band.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: Are any of these songs you used to do for real?

Mr. GERVAIS: No, no, no, no.

GROSS: Good. I was really hoping you'd say that.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah. No, of course not. No, I wrote those especially for the

show, and they weren't spoof songs. They were meant to be sort of like more

inappropriate. "Freelove Freeway," I'm fascinated when British people who've

never been out of their own town start writing songs about what it would be

like to cross America. You know, they might as well talk about space travel.

And I just thought it was--again, the joke there wasn't that he was bad or the

songs were comical, it was the fact that it was so inappropriate. He's meant

to be leading a training session, but he wants to show off. And I love that.

Same as, like, people who take a guitar to a party. I just want to go, `What

are you doing?' You know, it's just like, `Shut up.' So, no, I just

thought--I just found it amusing that, again, a 40-year-old man is meant to be

doing something about customer care, just wants to talk about being Bruce

Springsteen.

GROSS: The other great thing about this scene is he does all these horrible

things that make you so uncomfortable when a bad performer is singing in a

small room.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: He looks people in the eyes in a sort of dreamy way and...

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah. Excruciating, isn't it?

GROSS: Exactly.

Mr. GERVAIS: Absolutely excruciating. The white man overbite to show he's

really getting into it.

GROSS: Oh, yes. He bites his lips to show how sensitive he's being.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. Yeah, awful.

GROSS: Now as a musician yourself, is this something that you've done or that

you've just...

Mr. GERVAIS: Stop you there. Failed musician. Let's get it right.

GROSS: OK. That's fine.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: Is this something that you fear you've done yourself?

Mr. GERVAIS: Failed musician, I'll have you know. Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: So is this some...

Mr. GERVAIS: No, no, I hope I was never like that, and it was...

GROSS: But you've seen people be that way.

Mr. GERVAIS: And I wasn't 40, so I hope there's enough distance between me

and David Brent.

GROSS: My guest is Ricky Gervais, co-star and--star and co-creator of the BBC

America sitcom "The Office." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Ricky Gervais, co-creator and star of the British sitcom

"The Office."

"The Office" is shot as a mock documentary, because, you know, we're not only

seeing the scenes in the office, there are scenes in which the individual

characters are talking one-on-one behind the scenes with the camera, sharing

their insights into the office and their opinions of theirselves and their

personal philosophies. Why did you want to shoot it as a mock documentary?

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, that sort of seemed the most obvious way to shoot it, for

a few reasons. One, we'd come out of, in England, about five years where

docu-soaps were like the biggest thing on television. Normal people being

followed around at work, and there was one called "Hotel," one called

"Airport," and if you shoot like 10 people in a job, one of them's usually the

character, and they were getting a bit famous. They were getting their Andy

Warhol 15 minutes. And I was fascinated by that, that celebrity, that D-list

celebrity, people's just quest for fame on any level. I've always been

fascinated with why people just want to be famous. You speak to people, like,

`Oh, I want to be famous,' and you say, `As what?' They go, `It doesn't

matter.' And I've never understood that.

And I've thought the best way to shoot it would be with their consent. So if

it was a close narrative and this guy was going around, you'd think, `Well,

why is he acting like that?' Well, because the camera's there, you go, `Oh, I

get it. He thinks he's brilliant. He thinks the camera's his friend, and he

doesn't learn.' You know, if he just sat down and said, `Get the cameras out

of there, life would be OK. But because he thinks this is his salvation, it's

so much worse.' So that's why really. It just wrung out the awful,

cringeworthy nature of the whole thing. And particularly when he looks down

the lens at you, you suddenly go, `Oh God, he's looking at me,' and it makes

it even more awful to watch, 'cause it suddenly draws you in, 'cause

embarrassment is sort of catching. If someone embarrassed themselves, you're

sort of embarrassed as well.

GROSS: I've got to get in another scene here, and this is a scene from the

second season of "The Office," which is now out on DVD, and in this season,

two branches of this paper office have merged so that there are new people in

David Brent's office now, and the manager from the second office is now David

Brent's boss, but David Brent is still overseeing, you know, some of the new

people that have come in. And, you know, he thinks he's so funny and he's

been telling this, like off-color joke about the virility of black men, and a

lot of people have been really offended by it. They've complained to his

boss. So here he is with the new people on the staff trying to explain

himself.

(Soundbite of "The Office")

Mr. GERVAIS: (As David Brent) Now some of you maybe didn't understand the

jokes I was making, or misinterpreted one and went to Jennifer. OK. Little

bit annoyed that you thought you'd go to Jennifer and not me. Who was it that

complai--and it's not a witch hunt. Just who was it that--OK, well, two of

you. Good. Right. Why did you think you'd go to Jennifer but not me?

Unidentified Woman #1: Because I don't know you and I didn't like the kind of

joke you were telling.

Mr. GERVAIS: So--wow.

Unidentified Woman #1: And I don't think somebody in your position should be

laughing at black people.

Mr. GERVAIS: It's funny that only two of you thought that, out of everyone,

but, you know, everyone's...

Unidentified Man #4: I didn't like it either.

Mr. GERVAIS: Right. Proves my point. Swindon, you're new. You don't

know me.

Unidentified Man #5: I'm not new and I found it quite offensive.

Mr. GERVAIS: Right. Well, he didn't, so...

Unidentified Woman #1: But what's he got to do with it?

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, if he doesn't mind us laughing at him, what harm's been

done, is what...

Unidentified Woman #1: Well, why is it that only black people should be

offended by racism?

Mr. GERVAIS: Good point. Yeah. First sensible thing you've said all day.

Yeah. Because I say, `Come on, come all, we're all the same, yeah.'

That's...

Unidentified Woman #1: So is that why you've only got one black guy in the

whole organization?

Mr. GERVAIS: Wrong. Yeah. Indian fellow in the warehouse, and there used to

be one--Indian fellow who used to work up here. Lovely chap. He left.

Didn't like it. Up to him, you know. If I had my way, the place would be

full of them. Wouldn't it, Gareth?

Unidentified Man #6: Yeah, well, half and half.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah. You are half and half, aren't you?

Unidentified Man #7: I'm mixed race, yes.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah. That is my favorite, yeah. Yeah. That is what I'm

trying to--that's the melting pot, please. So there's your racist for you.

GROSS: That's a scene from "The Office," season two. My guest is Ricky

Gervais, who plays David Brent and co-created the series.

Ricky Gervais, I love that scene. He's just doing absolutely everything

wrong. As if telling a joke wasn't problem enough, he just keeps...

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...getting himself deeper and deeper, and he has no idea what's wrong

with anything that he says, and I'm wondering what kind of situations you've

seen like this.

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, the thing is, another theme about it is obviously men as

boys, boredom, underachievement, wasting your life. But one of the other

scenes is those people who know what political correctness is and, you know,

David Brent isn't a racist, he isn't a homophobe, he isn't particularly

sexist, but to make sure you know he isn't, he acts inappropriately over the

top. He goes too far, you know. If he just acted normally, no one would

accuse him of those things, but he wants to overcompensate. Like when the

black guy comes, every chance he gets he sidles up to him and says things

like, `Oh, Denzel Washington's good, isn't he?' The guy goes--then he goes,

`Not my favorite, though. My favorite actor of all time is Sidney Poitier.'

And, of course, he's just trying to get in black references. He wants to go

up to him and go, `I'm not racist. I'm not a racist.' And it's just--he

doesn't know how to behave.

GROSS: You created this character of David Brent for a short that Steve

Merchant, your co-creator on the series, was filming. So was this a character

that you were already doing before you even did that short film?

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah. Well, no, no, it was a character I already had, and then

Stephen said, `That would make a good character for a sitcom basically,' and

so we shot a little demo of "The Office." We went back to where I used to

work, in my old office, and I sort of ad libbed around David Brent, and we got

20 minutes out of it in about a day, and we cut it together, and just to see

how it would look. And that's what we showed to the BBC.

GROSS: How did you first start performing?

Mr. GERVAIS: Sort of by accident. I was the head of speech at a local radio

station. And then...

GROSS: Does that mean like head of talk programming, head of speech?

Mr. GERVAIS: Exactly. Yeah. And I started popping up on air just doing bits

and pieces and, you know, got a few e-mails saying, `He's a funny guy. Who's

that?' And then they gave my own show. And then when I was doing my own

show, someone from Channel 4 phoned and said, `We're starting this new thing.

Do you want to do an audition?' And I did the 11:00 show. So it all sort of

started from there really.

GROSS: Can you describe what your radio show was like?

Mr. GERVAIS: Oh. Oh, dear, what was it like? It wasn't like any other radio

show. It's--I don't consider myself a broadcaster. I don't really think I'm

that articulate. I'm lazy. I barely open my mouth when I talk. I'm not very

good at deejaying, so that gives you some idea.

GROSS: Sounds great.

Mr. GERVAIS: It was a couple of blokes in a room talking like we did in a

pub, as opposed to going, `It's fast approaching 9:23. Well, coming up is

Radiohead. Those guys are great.' And when I first started, I sort of opened

the mike for the first time and I went, `And that's David Bowie,' and one mate

said, `Why are you talking like that?' I went, `I don't know.' And then I

just sort of put my feet up and started talking normally.

GROSS: You have a couple of comedy shows that you've done, stand-up...

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...one called "Animals" and one called "Politics."

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

GROSS: Tell us about "Politics." Are you actually political in it?

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, the joke is, I pretend to be. I come out like I'm gonna

try and change people's attitudes and, of course, I get everything wrong. And

so, for example, when I talk about Nelson Mandela, I say, `Nelson Mandela,

incarcerated for a quarter of a century, came out in 1990, so he's been out

for about 14 years, and he hasn't reoffended. I really think he's going

straight this time, which shows you prison does work.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: That's really funny.

Mr. GERVAIS: So it's stuff like that.

GROSS: So you kind of specialize on people who are incomprehending.

Mr. GERVAIS: Well, yeah. The jokes--I think the important thing is, the

joke's always got to be me. However subtle that is or obvious, I think at the

end of the day, a comedian's got to be the target, otherwise he's cold and

he's vain and he's less funny.

GROSS: Well, Ricky Gervais, a pleasure to meet you. Thank you so much for

talking with us.

Mr. GERVAIS: Thank you very much.

GROSS: Ricky Gervais stars in "The Office." It's shown on BBC America and is

now on DVD. I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "The Office"; music)

Mr. GERVAIS: (Singing) Going on, 'cause my baby's gone. She's gone. Yeah.

My baby's gone. She's gone, yeah. Gone away. She's gone. She's gone, yeah.

She's just gone. She's gone.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

Unidentified Man #8: That's pretty.

Mr. GERVAIS: Yeah.

Unidentified Man #8: Pretty, yeah.

(Announcements)

GROSS: Coming up, Tom Perotta talks about his new novel "Little Children,"

about a young wife raising her child in the suburbs, convinced she is living

the wrong life. Perotta also wrote the novel "Election," which was adapted

into the film of the same name.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Tom Perotta discusses his book "Little Children"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

"Little Children" is a new satirical novel about a young woman who is married,

raising her child in an upper middle-class suburb and she can't understand how

she wound up in the life she's living. She believes she's found some larger

drama and meaning in her life when she meets Todd, a father at the playground

who seems to be as alienated as she is. They begin an affair and think

they're falling in love. The author of "Little Children" is Tom Perrotta who

also wrote "Election," a satirical novel about a high school election which

was adapted into a film starring Matthew Broderick and Reese Witherspoon.

Perrotta's novel "The Wishbones" was about a musician who wants to be a rock

star but is stuck playing weddings.

In The New York Times book review of "Little Children," Will Blythe wrote,

`"Little Children" is an extraordinary novel about adultery and child raising

in a generic American suburb.' Here's a reading from the beginning of the

novel.

Mr. TOM PERROTTA (Author): `The young mothers were telling each other how

tired they were. This was one of their favorite topics, along with the

eating, sleeping and defecating habits of their offspring, the merits of

certain local nursery schools and the difficulty of sticking to an exercise

routine.

`Smiling politely to mask a familiar feeling of desperation, Sarah reminded

herself to think like an anthropologist. "I'm a researcher studying the

behavior of boring suburban women. I am not a boring suburban woman myself."

`"Jerry(ph) and I started watching that Jim Carrey movie the other

night,"--this was Cheryl(ph), mother of Christian(ph), a husky

three-and-a-half-year-old who swaggered around the playground like a mafia

chieftain, shooting the younger children with any object that could plausibly

stand in as a gun--a straw, a half-eaten banana, even a Barbie doll that had

been abandoned in the sandbox. Sarah despised the boy and found it hard to

look his mother in the eye. "The Pet Guy?" inquired Mary Anne, mother of

Troy(ph) and Isabelle(ph). "I don't get it. Since when did passing gas

become so hilarious?" "Only since there was human life on earth," Sarah

thought, wishing she had the guts to say it out loud. Mary Anne was one of

those depressing super moms, a tiny, elaborately made-up woman who dressed in

Spandex workout clothes, drove an SUV the size of a UPS van and listened to

conservative talk radio all day. No matter how many hints Sarah dropped to

the contrary, Mary Anne refused to believe that any of the other mothers

thought any less of Rush Limbaugh or any more of Hillary Clinton than she did.

Every day Sarah came to the playground determined to set her straight, and

every day she chickened out.'

GROSS: That's Tom Perrotta reading from his new novel "Little Children."

Tom, the main characters in this novel are kind of living the wrong life, like

Sarah, the main character who you were just reading about. This is not the

life she wanted. She didn't plan on being a mother living in the suburbs. In

college she had been bisexual, she had an affair with a woman, she was

immersed in critical gender studies, she worked at a rape crisis hotline, she

was hoping to be a feminist film critic. I think a lot of people feel that

they ended up in the wrong life. How did she get there?

Mr. PERROTTA: Well, I think she got there the way a lot of people get where

they end up. The years after college were particularly lonely for her. She

was directionless. She tried graduate school, was very excited for a while

but then didn't like teaching very much, worked at Starbucks, had some

affairs. And somehow there was a man at Starbucks, an older guy, who was also

a little bit lost who found his way toward her. And, you know, they fell in

love, so she thought, got married and suddenly found herself in the exact--I

mean, she didn't have a profession, he did. Basically, there was a kind of

economic determinism to it that's almost 19th century to her.

I also think there's something about the generation, that's my generation, of

people that went to college in the '80s and '90s when feminism was still, I

think, a really dynamic force in American culture. And, you know, we, in our

minds, imagined a whole different set of social arrangements and family

arrangements. And something happened, you know. I mean, when I was first a

parent and at the playground, I was suddenly surprised to find myself often

the only stay-at-home dad. You know, I wasn't a full-time stay-at-home dad

but I was doing about half-time child care. And if I took my kids to the

playground during the workday, I was usually the only man there. And I think

that, in the same way that I probably felt surprised by that and a little bit,

you know, like what had happened? Where was the world that we thought we were

entering? I think someone like Sarah, who was, you know, really in the

vanguard of this sort of thing, probably felt it quite a bit more acutely than

I did.

GROSS: Well, I want to get back in a minute to you being the only dad in the

playground but, first, I want to talk about another father, a father in your

novel who is the father in the playground. He's one of the few guys who goes

there with his kid, and he ends up having an affair with Sarah. But he, too,

feels like he's not quite in the right life. His thing when he was in college

was football and now he's studying for the bar exam kind of

unenthusiastically. How did he get stuck in the wrong life?

Mr. PERROTTA: Well, he's not sure about that. His mother died when he was

in high school and he'd become a sort of high achiever in the wake of that.

And life had been completely effortless for him through--he's a very

good-looking guy, very smart guy. He married this beautiful woman, he got

accepted into law school. And at some point between finishing law school and

passing the bar, you know, they had a kid. His wife was working full-time, he

was home with the kid. And what seemed to happen to Todd was that he just

lost interest in the adult trajectory that he'd been on. I mean, in some

ways, he's a male version of one of those women CEOs who suddenly decides that

she doesn't want to, you know, run the company, she wants to be home with her

kids. In some sense, parenthood does appeal to him. I mean, in a way, his

wrong life is the exact opposite wrong life of Sarah's. I mean, he's a man

who's supposed to have a high-powered career who somehow has decided he likes

the rhythms of being home with the kid all day and likes the rhythms of

adolescence, likes the rhythms of sports. He likes everything but the rhythms

of responsible adulthood.

GROSS: Do you feel like you're living the right life?

Mr. PERROTTA: I feel like I am now. I think that I was one of those people

who was very shaken by parenthood, not so much because I didn't like it

because I really did enjoy it and I found it kind of thrilling and mesmerizing

the way a lot of people of my generation, you know, do. At the same time, I

wasn't where I wanted to be professionally and, you know, I was shocked by the

time burdens that were placed on me. And, you know, I had gone to great

lengths to, you know, invent myself as somebody who, you know, had a certain

level of coolness, or so I thought. You know, I think parenthood is about the

least cool role you can take on. And so for anybody who has any sort of, I

think, you know, bohemian leanings or aspirations or self-delusions--you know,

you can put it in all those ways--parenthood is a jolt to, you know, the very

fiber of your being.

GROSS: I'm sure that's true and why is that? What is it that's so, like,

uncool about parenthood, unhip about parenthood?

Mr. PERROTTA: Well, for one thing, right, coolness must have something to do

with a kind of--I mean, there's a certain sexual component to it and, as a

parent, you know, your sexuality is, I think, you know, for good reasons, you

know, it goes on the back burner. You know, probably even at home but

certainly in a kind of public way.

But then, you know, you have to argue with your kids, you have to, you know,

try and mollify them when they're screaming, you have to walk around with, you

know, vomit on your shirt. In fact, you know, one of the roots of this novel

was a strange event that happened to me when my daughter was very young and I

used to carry her around in a backpack which I really enjoyed. But one night

I was out for a walk with her and this guy who was a teen-ager just started

taunting me from a doorway. He would call me--he would say, `Hey, you look

like an idiot' or something like that. And I remember getting like, you know,

oddly enraged and sort of forgetting for a second that I had my daughter on my

back. And, you know, I turned and said, `Who are you talking to?' And, you

know, we had this sort of odd, heated exchange which is not something that's

common in my life. And at a point, he just started laughing and said, `What

are you gonna do, fight me with that thing on your back?' You know, that

thing on my back being my daughter.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. PERROTTA: And I thought, you know, what's the matter with me? Why am I

acting like a, you know, angry 16-year-old when I'm, you know, 30 years old

and I have a small child on my back? And it was just a moment that really

stuck with me. And about 10 years ago I tried to write a story that was

called This Thing on my Back that was about, you know, somebody kind of very

reluct--well, no, it's not even reluctantly, it's just somebody finding out

that his, you know, adolescent identity was still burning inside of him while

he was, you know, a responsible adult with a child to care for.

GROSS: How old are your children now?

Mr. PERROTTA: My daughter's 10 and my son is seven.

GROSS: In the acknowledgements to your new novel, "Little Children," you end

it by saying, `Mainly, though, I'd like to thank Nina(ph) and Luke(ph) for

letting me tag along at the playground.' So I assume that Nina and Luke are

your children, that you spent a lot of time taking them to the playground and

using that as inadvertent research for your novel. You have a really funny

paragraph about what the few men who come to the playground with their

children are like, what they look like and how they behave. I'm going to ask

you to read that paragraph for us from "Little Children."

Mr. PERROTTA: OK. "Most of the men who showed up at the playground during

the work day were marginal types: middle-aged trolls with beards and pot

bellies, studiously whimsical academics who insisted on going down the slide

with their kids, pitch-hitting grandfathers providing emergency day care,

sheepish blue-collar guys who wouldn't meet anyone's eyes, the occasional

cooler-than-thou hipster with a flexible schedule."

GROSS: Were you the occasional cooler-than-thou hipster with the flexible

schedule?

Mr. PERROTTA: I was somewhere between the hipster with a flexible schedule

and the studiously whimsical academic. But there was some part of me that was

also the sheepish blue-collar guy that wouldn't meet anyone's eye.

GROSS: All right. What was it like to be one of the few fathers regularly at

the playground with your children?

Mr. PERROTTA: You know, probably some women who were at the playground would

deny this, but I was actually I thought made to feel somewhat unwelcome.

There was just some sense of, you know, `What is he doing here?' And if you

tried to strike up a conversation, sometimes there was a little bit of reserve

or coolness.

But what did happen and I think is something I tried to use in the novel was

that occasionally there would be a woman who, for some other reason, was not

part of, you know, this sort of the core female society, the core mother group

of the playground. And occasionally I would get into conversations with these

women who, for whatever reasons, were also outsiders. And that's the dynamic,

I think, between Todd and Sarah, they both feel somehow excluded from this

core maternal click at the playground and it creates a kind of instant bond of

intimacy between them.

GROSS: My guest is Tom Perrotta. His new novel is called "Little Children."

We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Tom Perrotta, author of "Election" and "The Wishbones."

His new novel, "Little Children," is a satirical novel about a woman, Sarah,

who once thought she'd be a feminist film critic and is now feeling quite

alienated as a wife and mother in the suburbs. She's attracted to a young

father named Todd whom she met at the playground.

There's a section in which Sarah goes shopping for a bathing suit and she

wants to get a bathing suit that makes her look very attractive which was

difficult. And I think most women agree that buying a good bathing suit is a

real challenge and it's something a lot of women are particularly

self-conscious about. What kind of thinking did you do to try to write that

scene from a woman's perspective?

Mr. PERROTTA: You know, I think for men, it's very interesting the point

where you realize how, you know, nervous and anxious women get about these

things because, of course, for most men, I think the idea of a woman in a

bathing suit is, you know, kind of a very exciting thing and--due to the fact

that women are probably much harder on themselves and their bodies than men

are at a certain point. So I think that--again, it seems like a pretty

pervasive thing. I mean, I read some catalogs, you know, and--for instance,

if you read, you know, the Lands' End catalog, there's a very kind of--you

know, the voice of the catalog is, you know, `This is coverage, this is going

to, you know, save you from certain embarrassing issues that will conceal the

problem areas.' I mean, you know, it was really just right there in the

forefront. And maybe, you know, I was reading something that men don't

normally pay attention to. You know, we're just supposed to look at the

pictures, but it was, you know, right out in the front, you know. And I've

certainly heard women, you know, talk about the bathing suit dilemma.

GROSS: Do you want to read that paragraph?

Mr. PERROTTA: Sure.

GROSS: In this paragraph, Sarah is shopping with her young daughter Lucy(ph).

And while she's, you know, trying to find a good bathing suit, she also has to

keep track of where her daughter is.

Mr. PERROTTA: That's right. And I should say that Sarah is hoping to go to

the town pool and reconnect with Todd after their first intense flirtation, so

she's given this a lot of thought.

"When she finally made her selections, she dragged Lucy into the fitting room

and told her to stay put while she tried the suits on over her generously cut

gray cotton panties which kept poking out and spoiling the effect. Not that

there was much to spoil. The first suit hugged her hips and waist perfectly

but looked about three sizes too big on top. The second fit nicely across her

chest but drooped off her ass like a tote bag. She thought the third suit

looked OK. It was a black one-piece, daringly low-cut with a series of oval

cutouts traveling up the side. But when she left the fitting room to consult

with the saleslady in front of the three-way mirror, the woman hesitated for a

long time before answering. `I wouldn't,' she said finally."

GROSS: Yeah, I love that. You know when the saleslady, who needs to sell you

clothes, thinks something looks bad, it really looks bad.

Mr. PERROTTA: I know. Usually she'll say she would. OK.

GROSS: Thanks for reading that. Did you talk with your wife a lot about

certain things, you know, before writing the book or while writing the book,

just to get, you know, into a kind of female point of view of things?

Mr. PERROTTA: I think, you know, when you live with somebody, you get their

point of view...

GROSS: Good point.

Mr. PERROTTA: ...kind of around the clock. I'm sure I had to ask her certain

questions and she'd be very happy to help me if I did, but I think it's more

like, you know, a steady stream of information that I get from her and from,

you know, other women friends.

GROSS: You refer to "Madame Bovary" a lot in the book and, in fact, Sarah's

reading group is reading "Madame Bovary." Did you reread "Madame Bovary"

before writing "Little Children"?

Mr. PERROTTA: I did, yeah.

GROSS: And, you know, for Sarah, she finds it's just a very different book

than the book she remembers reading when she was younger. She's identifying

with it in a different way and seeing meaning in it that she didn't see the

first time around. Did it read differently to you than it did the first time

around?

Mr. PERROTTA: Well, I'm certainly reading it through her eyes and I think,

you know, her journey kind of reflected--or my journey reflected hers. I

mean, to read a lot of novels in an academic context in the mid- to late '80s,

early '90s meant that you often got a feminist interpretation, particularly in

a novel like "Madame Bovary" where, you know, a previous generation would've

talked about it on a level of craft and style and, you know, Flau Bert's

doctrines of the novel, I think a lot of us read it through a kind of feminist

lens of here's a woman who, for all sorts of cultural and economic reasons,

you know, is trapped and has this one means to rebel but even that is kind of,

you know, doesn't give her any room. And, you know, she suffocates despite

her best efforts to rebel against this, you know, oppressive society whereas

Sarah, you know, would've been the first one to, you know, have approved of

that reading. She'd been a critical gender studies major and speaks a lot

about her teachers and their thoughts about phallocentrism and, you know, male

domination of the culture. But instead, her second time around, she's reading

it as if she were Madame Bovary. She's completely identifying with the

character. And her reading of it in the end is not that Madame Bovary was

wrong to want some love to save her from the tedium of her life, she just

didn't find a partner worthy of that passion. And Sarah, for a brief moment,

thinks she has found a partner worthy of that passion and that partner's Todd.

GROSS: My guest is Tom Perrotta. His new novel is called "Little Children."

We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Tom Perrotta. His new novel, "Little Children," is a

satire about marriage and parenthood in the suburbs.

You've written about different stages of life from high school in "Election"

to college to young adulthood, young parenthood. Do you think that your

writing style has changed when telling stories of people of different ages?

Mr. PERROTTA: Yeah, and I'm not sure what to attribute that to, but I look

back at "Bad Haircut" recently which is a book that means a lot to me. I

wrote it when I was--I started when I was in my late twenties and...

GROSS: It's a collection of short stories.

Mr. PERROTTA: Short stories about a boy growing up. It's almost like

snapshots of this boy from age eight to age 18. And occasionally, you know,

I'll read it in public or I'll go back and look at it, and the style is very

different from the style in this book. It's much more kind of Hemingway-esque

or Carver-esque. The sentences are very short, very clipped. There's not a

whole lot of, you know, internal monologue for the main character. Even

though it's done in first person, it's done in that minimalist style of, you

know, here's what happened, here's what someone said.

There was a lot of irony generated by, you know, the way that the sort of bare

bones of the story are juxtaposed. But, you know, the style is a lot more

sort of choppy and less fluid and less internal than what you get in "Little

Children." And, you know, I might say that that's because, you know, these

older characters have richer inner lives and I couldn't write about them in

the same way. That's one possible answer, and the other is just that, you

know, that minimalist voice which I really admired and loved in Carver and

Hemingway wasn't completely mine and that, you know, now I'm beginning to grow

into a voice that's a little more my own.

GROSS: You know, you've said that one of your interests is, you know, writing

in a period that's obsessed with youth culture. And you started writing when

you were in your twenties--you started publishing I should say--Yes?--when you

were in your twenties?

Mr. PERROTTA: Well, actually, I started...

GROSS: Thirties?

Mr. PERROTTA: ...writing those stories when I was in my twenties, but they

didn't get published until I was in my early thirties, "Bad Haircut."

GROSS: Has it been difficult for you to make that transition out of youth

culture? As a writer and as a person to not be, like, the young person

anymore or the young writer?

Mr. PERROTTA: No, I just practice denial on an extreme level. You know...

GROSS: Well, I guess I'm wondering, like, what's your approach to, like,

getting older in a culture that is so kind of youth-obsessed and so in denial

about getting older?

Mr. PERROTTA: Well, I think, like a lot of people my age, there is that kind

of denial. I mean, I know that when my first kid was born, you know, one of

the first things I did was get a mountain bike and--at some period, you know,

where, you know, I think I take way better care of my body now, spend a lot

more time exercising now than I did when I was young. And, you know, I

was--at least until a couple years ago, you know, I was the kind of person

who, you know, I would still get carded and, you know, when I'd go take out

books from the library in the college where I taught, they'd say, `Oh, you're

not a student?' But recently I've started to go gray and I don't get that

anymore. You know, I'm trying to do it with some combination of, you know,

grace and defiance, you know.

As for the writing, I mean, I have to say that I'm still a little bit 10 years

behind. I mean, I'm in my early 40s, but the characters in "Little Children"

are in their early 30s. I do think I'm still looking backwards and trying to

figure out, you know, what it is that I've gone through. And that seems OK

for a writer to look backwards in that sense.

GROSS: Are you wondering what it's going to be like to watch your kids go

through the periods in life that you've already written about? And you'll be

in the position of parental authority figure.

Mr. PERROTTA: Yeah, I do wonder about that. And, you know, my hope is just

that--you know, I really do think I grew up--you know, I was in high school in

the mid-'70s. I think it was a time of, you know, just really the

deepest--I mean, well, it's probably a hangover from the deep generation gap

of the '60s. I think, you know, it seems much easier for parents to be close

to their kids and to feel like they're on the same cultural page with them

right now than when I was younger. So I'm hoping in a way that the kind of

difficulties that I went through with my parents, which were just garden

variety--they didn't, you know, understand why I wore my hair the way I did,

what kind of clothes I wore, the music I listened to and there were just a lot

of kind of superficial clashes, whereas, you know, now it seems to me that

it's easier for kids to be close to their parents. In fact, a friend of mine

who is a dean at a college was saying that a lot more parents come and, you

know, stay with their kids, you know, in their room in college. You know, one

mother would come every weekend and sleep on the couch and it was all right

with all the roommates. And I'm not saying I'm going to be that kind of

father, I just mean that I think there's a little bit less that sense of

parents as kind of an unwelcome alien intrusion into the world of kids, but

maybe I'm being very optimistic 'cause I don't want to, you know, be on the

wrong end of that divide.

GROSS: Well, Tom Perrotta, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. PERROTTA: Oh, well, thanks for having me, Terry. I enjoyed it.

GROSS: Tom Perrotta's new novel is called "Little Children."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.