Other segments from the episode on February 14, 2007

Transcript

DATE February 14, 2007 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Independent filmmaker John Waters discusses his new CD,

"A Date with John Waters," a collection of his favorite love songs

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

If you want to celebrate Valentine's Day without getting too sugary, you've

come to the right place. We're going to hear some love songs selected by John

Waters, the independent filmmaker who became famous for bad taste with his

1972 midnight movie classic, "Pink Flamingos." When his 1988 movie,

"Hairspray," was adapted into a hit Broadway musical, he crossed over to the

mainstream. That doesn't mean he's given up on transgressive movies. He now

describes himself as a filthy elder. He's put together a new CD of his

favorite love songs. The collection is called "A Date with John Waters." Some

of the tracks are really strange. Some of them are really great. Before we

talk with Waters about love, let's hear Shirley and Lee. They're best known

for their 1956 recording "Let the Good Times Roll." This is "Bewildered."

(Soundbite from "Bewildered")

SHIRLEY: (Singing) "Bewildered, life...(unintelligible)...love dream of you

Where is the love I knew? Why did we part?"

LEE: (Singing) "Bewildered..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: I asked John Waters why he included this track on his CD, "A Date with

John Waters."

Mr. JOHN WATERS: I'm a huge fan of Shirley and Lee. This song was mostly

known as a signature song by James Brown. I had never heard Shirley sing

this. Shirley and Lee, of course, had big hits with "I Feel Good" and "Let

the Good Times Roll" in the '50s, but they sang many, many, many other songs,

and I think she was the first person that introduced the nasal voice female

vocal that went on to maybe Kathy Linden, "A Thousand Stars in the Sky," and

Angel Baby, and I'm just so happy that Shirley never took her cold pill that

day, or maybe they didn't have cold pills in the '50s.

GROSS: This is a great old photo of you on the cover of your new CD, "A Date

with John Waters," and it's you kind of--it looks like you're reclining with a

very kind of "come hither" look.

Mr. WATERS: Yeah, yeah. I've been saving that picture...

GROSS: Your collar turned up...

Mr. WATERS: Yeah, my dirty collar. Everybody's pointed out the white

collar's very dirty on that jacket. Well, it did come from a thrift shop.

That was at the Dovial film festival, the first time I ever went to France, in

probably about '76, and it was taken--the picture was taken by Marsha Resnick,

who very much covered the punk rock scene in those days in New York, and I've

had that picture in a box for--since then, thinking one day I'll use this for

something.

GROSS: Did she pose you like this?

Mr. WATERS: Well, I don't remember. It was a whole photo shoot. I don't

remember really. I do remember that Gloria Swanson was at that film festival

when she was still alive, and I watched her in action, so amazingly--when you

talk to her there was paparazzi around always with her but she would never

pretend that they were there but she would put her face up to cover

unflattering angles that she could see they were taking, so it looked like she

was doing kabuki when she was talking to you but she never acknowledged there

were photographers there, but she would just block her face if she could see

they were taking it from an unflattering angle. So maybe she affected me that

way, I don't know.

GROSS: What was your idea of romantic sophistication like when you were

young?

Mr. WATERS: Mmm, when I was young. Certainly Hollywood movies. Certainly

Douglas Sirk, really. His movies were melodramas, and at the time they were

made fun of by the critics. They were called women's pictures, and they were

always with Lana Turner and Rock Hudson, and they were--people went blind or

people could never get back to the one they loved, and I think, as much as I

loved Douglas Sirk's movies, he damaged all of us from our generation because

we believed this is what love should be like when, of course, it couldn't be,

and I finally did meet Douglas Sirk, way, way later in life, at the Berlin

Film Festival with Fassbinder, and they were about the oddest couple but they

actually hung out, and I think Fassbinder made Douglas Sirk famous again by

praising his movies and remaking some of them. And that's why I put on this

album the theme song to "Imitation of Life," which is probably one of Sirk's

most famous movies, and the title song by Earl Grant. That album has been out

of print for many, many years, and collectors have been looking for that song,

so that's why I put it on here. It's a good make-out song. It's a good song

to drink and miss somebody by. I've seen--I had a friend that used to drink

heavily in my apartment and play the song over and over and over and over

missing his ex-boyfriend. So, basically, I think it's a good song for that.

It's a good Valentine's song.

GROSS: And before we hear it, I mean, just say a little bit about what the

plot is like from this 1959 movie.

Mr. WATERS: "Imitation of Life." Let me think now. It's Lana Turner. She

becomes--she's poor and then she becomes a movie star and she claws her way to

the top, always with her maid. And her maid has a daughter who passes for

white and falls in love with Troy Donahue, and he finds out that she's black,

and there's lots of racial tension all through it, and it's a real weepy--when

the maid dies and the funeral at the end of "Imitation of Life" is the most

over-the-top, tearjerking melodramatic funeral with Mahalia Jackson wailing in

the background. It's actually what I want my funeral to be like.

GROSS: Well, let's hear the theme. We're not going to think about that too

much. Let's hear the theme from "Imitation of Life," and this is Earl Grant.

(Soundbite from "Imitation of Life")

Mr. EARL GRANT: (Singing) "What is love without the giving. Without love,

you're only living an imitation, an imitation of life. Stars above in flaming

color. Without love they're so much duller. A false creation, an imitation

of life."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Now when you were loving these Douglas Sirk movies when you were

younger--I mean, do you think that they became an influence on your

filmmaking, and I'll give you an example of a place in which I think Douglas

Sirk was definitely an influence and...

Mr. WATERS: Mmm.

GROSS: ...that's in "Polyester," in the character that Divine played who is

this like long-suffering housewife whose husband turns out to be no good

and--but she has a big heart and she's going through all these like trials and

she's misled by a handsome young man.

Mr. WATERS: Completely, it's the movie that I did that was most like Douglas

Sirk. Even the opening. The coming--going over the neighborhood and with Tab

Hunter and Debby Harry singing together. It was the movie--you know, many of

the Douglas Sirk movies, I didn't really see as a child. I saw them later in

life...

GROSS: Mm-mmm.

Mr. WATERS: ...when I was--when making my movies myself when I was an adult.

So he's influenced so many young filmmakers. I mean, you know, what was the

movie Todd made? The remake. "Far from Heaven."

GROSS: Yeah. That was great.

Mr. WATERS: That was very much a Douglas Sirk movie.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. WATERS: Yeah. And so you're right. That is the movie most of mine that

was heavily influenced by Douglas Sirk, and we all watched the movies before

we made them, and it was the first time that Divine played a real character.

We had established this fictitious character of Divine that was kind of Jane

Mansfield and Godzilla put together, and then it was a shock to people to see

him playing a fairly unattractive, miserable, weak housewife but she started

to get very good reviews because it was such an against type role but very

much a Douglas Sirk character, yes.

GROSS: Did you see Douglas Sirk's movies as unintentional camp or as really

great filmmaking?

Mr. WATERS: I think they're really great filmmaking. I think Douglas Sirk

always knew they were ironic but the style of the movies, the reflections and

the artificial light that's coming from nowhere and all the mirror shots and

that great shot where she's just looking in the television, lonely, and

reflects her own face in it. And I think that he was a very, very good

filmmaker. I think Andrew Sarris was the first critic that ever actually

praised him. He was in the '50s always got bad reviews. And then Fassbinder

I think is really the one that completely was responsible for the revival of

Douglas Sirk, and I think today he is--many, many young filmmakers, you can

see the influence of Douglas Sirk's films.

GROSS: Well, my guest is filmmaker John Waters, and he has a new CD that's a

compilation of love songs, falling in and falling out of love, and the CD is

called "A Date with John Waters."

Let's listen to another track from your CD, and I thought we could play

"Johnny, Are You Queer?" Tell us something about why you chose this and who's

performing it?

Mr. WATERS: Well, it seems like a fair question on an album. The only girls

that come on to me any more are biker girls. For some reason, they don't get

it, and I'm always--and they're rubbing up against me, and I think, `Haven't

you heard by now?' But they haven't I guess, or maybe they think that they're

going to change, I don't know. So I think it's a great funny song that's a

really fair date today. Most women I know that ended up in the arts as

actresses, most heterosexual women, their first boyfriend was gay, and they're

not sorry about that. They became friends and then they moved on and found a

great straight boyfriend, but I think it's a very common question today to ask

if a girl likes a guy, `Hey, are you queer, by the way? Just tell me now.' I

mean, it seems a fair question today. It's part of dating.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear "Johnny, Are You Queer?" featuring Josie Cotton.

(Soundbite from "Johnny, Are You Queer?")

Ms. JOSIE COTTON: (Singing) "Johnny, what's the deal, boy? Is your love for

real, boy. When the lights are low, you never hold me close. Now I saw you

today, boy, walking with them gay boys. Now you hurt me so, now I gotta know.

Johnny, are you queer? 'Cause when I see you dancing with your friends, I

can't help wondering where I stand. I'm so afraid I'll lose you..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's "Johnny, Are You Queer?" one of the tracks on John Waters' new

CD compilation which is called "A Date with John Waters," and it's a follow-up

to an album he had a couple of years ago of his favorite, and unusual,

Christmas songs.

Since your album is all about love...

Mr. WATERS: Yes.

GROSS: I mean, can I ask you like when you knew you were gay?

Mr. WATERS: Mmm. Probably the first time I saw Elvis Presley. And my

parents were appalled. I mean, before he was really famous, when he was a

rock and roll hillbilly. When he first came out on "Louisiana Hayride." Those

days. I thought, `Oh, my God, it's a space alien, something here.' But I felt

something that I realized that I was maybe responding in a way that was not

typical to the other boys in my class. Let's say I paid more attention to

Elvis than the baseball game.

GROSS: Do you have like a coming-out story of like when you told your parents

and what their reaction was?

Mr. WATERS: No, that's like coming out's too corny for me, really. I just

figured everybody else knew really. I was always amazed. I was on the cover

of a paper called Gay Times in about 1972 or something when the "Pink

Flamingos" came out. So I basically--I don't know, I always just assume--you

saw my movies. But to me, I never fit in the gay world either. I still

don't.

GROSS: In what sense do you feel like you don't?

Mr. WATERS: Well, I've never been to the gym. I have no desire to. I want

to look like a junkie. I like women, too, for friends. Many of my friends

are straight. I don't know. I don't like to dance in public. There's lots

of things that I don't fit in. But I always liked all minorities that don't

get along with other minorities because then you really have a sense of humor.

So I like bars that are totally mixed--straight, gay, undecided--and that is

more fun to me because then it's more interesting.

GROSS: My guest is filmmaker John Waters. His new CD is a collection called

"A Date with John Waters."

More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is independent filmmaker John Waters. He's best known for

his midnight movie classic, "Pink Flamingos," and for his movie, "Hairspray,"

which was adapted into the hit Broadway musical. He's put together a CD of

his favorite love songs called "A Date with John Waters."

So, I want to play another selection from your compilation, "A Date with John

Walters," and this time I thought we'd play something by somebody who you've

worked with a lot, and it's the actress Mink Stole...

Mr. WATERS: Right.

GROSS: ...and the song is "Sometimes I Wish I Had a Gun." Tell us a little

about her and your working relationship with her. She's been in most of your

movies...

Mr. WATERS: Yes. Mink is...

GROSS: ...before we hear the record.

Mr. WATERS: ...Mink has been in every one of my movies, I believe, since

"Mondo Trasho." She might have missed one when she was in a different city.

But she has always been a character actress in all my films. She was usually

pitted against Divine and Divine usually won. Divine killed her many times in

my movie. She's been around forever. Her real name was Nancy Stole, and I

knew her--I lived with her in a tree fort in Provincetown, is how we first

met. And Mink was great. I mean, I never knew that Mink sang though. This

new song where I think she sings really well is brand-new. I mean, she's

doing this singing right now. She lives in Los Angeles, and she sent me this,

and I had no idea that she could sing like this. I knew Mink could act. I

knew Mink was funny. I knew Mink could do a lot of things but I never knew

she could sing in kind of a Julie London kind of way. So I was thrilled to

put her on the album, and as I say, I don't think there's any songs on this

album that are campy, even Edith Massey. I don't think anybody is going to

think Mink's song is campy, but maybe Edith Massey, who sings "Big Girls Don't

Cry." But to me, campy is so bad it's good and the same with my Christmas

album. I didn't pick any of these songs because I think they're bad. And in

Mink's case, I was just kind of wowed by her talent. I think she's great.

GROSS: Well, let's hear it. This is Mink Stole singing "Sometimes I Wish I

Had a Gun."

(Soundbite from "Sometimes I Wish I Had a Gun")

Ms. MINK STOLE: (Singing) "Sometimes I wish I had a gun, so you and I could

be alone. You'd be my hostage for the day, and you'd do just what I say. I'd

aim it at your arms and make you wrap them 'round me. I'd aim it at your lips

and make you say you love me. I'd aim it at your eyes and give a look of

love. And we'd be happy, baby. Sometimes I wish I had a gun. Sometimes I

wish I had a gun whenever you go walking by. You wouldn't give me that look

when my gun caught your eye. I'd aim it at your arms. You'd wrap them 'round

me. I'd aim it at your lips and make you want to kiss me. I'd aim it at your

eyes and give a look of love. And we'd be happy, baby. Sometimes I wish I

had a gun."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Well, since we just heard from Mink Stole, who you've worked with in a

lot of your movies, I thought this would be a good time to pay tribute to Van

Smith...

Mr. WATERS: (Unintelligible)

GROSS: ...who was a makeup artist for a lot of your films and he died in

December.

Mr. WATERS: He was more really the costume designer most of the time.

GROSS: Costume designer, yeah.

Mr. WATERS: He did makeup, too. He did makeup up to the end, but I think he

was most famous for the costumes. He did Divine's fishtail gown in "Pink

Flamingos," Ricki Lake's roach dress. He did the costumes for every movie

from "Pink Flamingos" up until "A Dirty Shame," and he was going to do my next

movie with me. He was a dear friend. He was--I always joke the Mount

Rushmore behind my films was Van Smith for the costumes and Vincent Peranio

for the production design and Pat Moran for casting. And I hope I get

obituaries that were as amazing as his. I mean, The New York Times said he

was a terrorist and an artist. Boy! That's a good review.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. WATERS: Yeah. They were pretty great, and he died just of a heart

attack. He's the only person I ever knew that got a pacemaker 10 years ago

and never went back to the doctor and continued to smoke so it wasn't about

health advice, but the doctor had told him if he continued to smoke he would

be dead in a year, and he continued to smoke and lasted 10 years. So oddly

enough, Van didn't even know he died. He just dropped dead, but he was a

major, major person in my films, and I owe him great credit for whatever

success I've had.

GROSS: How did you meet him?

Mr. WATERS: I met Van--he went to the...(unintelligible)...Institute and he

knew some of the people--I took LSD with him if you really want to know the

truth is how I met him.

GROSS: And when you took LSD together, what was the trip like? Were you...

Mr. WATERS: Which is--it wasn't just...

GROSS: ...talking about movies or...

Mr. WATERS: Well, gee, I don't remember, you know. When LSD--we were the

chair. Let's just say that it wasn't just Van and myself. It was Divine,

David Lochary, Pat Moran and many of the people that were the nucleus of the

making of my films, and Van was an art student at the time, and I remember two

of the things that Van did was, he really was responsible for Divine's look,

and I said to him once, `Just do something weird to his hairline,' and Van was

the one that thought up shaving his hairline back basically to leave more room

for eye makeup. Van believed that the human face did not have enough space on

it for the eyebrows that he wanted to put on.

And another thing I remember, when Divine was still Glen Milstead and didn't

completely believe he was Divine yet, I had moved to San Francisco and then

the films had caught on "Mondo Trasho" and "Multiple Maniacs at the Palace

Theatre," and a guy named Sebastian who was the promoter there, a great guy,

said, `Bring Divine out. Bring him out here and we'll make him a star here.'

So he had no money. Divine was home and I said to Van, `Get him, let's do

this.' So Van thought up this Divine look, put Divine in full drag, put him on

an airplane. He did not have one penny in his pitiful pocketbook that cost a

nickel from a thrift shop, and he went to San Francisco, got off the plane,

was received by the Cockettes, that were a bearded transvestite group, very

popular in San Francisco at the time, and he never went back. He was Divine

from then on, and I think Van gave Divine confidence to believe that he could

really do this, and I think that that was very, very important.

GROSS: You know, you mentioned that when you first met Van Smith you were all

tripping, and there's parts of "Pink Flamingos" that are really like a very

bad trip.

Mr. WATERS: Or a very good trip.

GROSS: Well, in your opinion.

Mr. WATERS: Certainly, we weren't tripping when we made those movies. That

would have been impossible.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. WATERS: You know, my mother always says, `Don't tell LSD stories to

young people.' But basically, nothing bad happened to me on LSD. If I had a

child today, and they told me they were taking LSD, I'd be uptight, but it

gave me confidence in a weird way, but many friends maybe that I took LSD with

at the time went on and became drug addicts and are dead so--but I think the

experiences we had certainly did give some influence on the look of Divine,

certainly. And when we used to take LSD, Divine would come in, unshaven, with

stubble, and put a towel around his head like a hat and shower curtain rings

as earrings and do Dionne Warwick's entire album while we were tripping while

the acid was coming off. So it was an experience you do remember, let's put

it that way.

GROSS: Van Smith must have designed a lot of really great, like

cheap--because you didn't have much of a budget--makeup and designs...

Mr. WATERS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...for the people in your movies.

Mr. WATERS: But the thing was--the tradition was that Van and I joked about,

on every movie, including the last one, there was a tradition that one of the

stars cried when they saw their costumes the first day. It always happened.

We waited to see who it would be.

GROSS: Can you give me an example?

Mr. WATERS: Ruth Brown in "Hairspray." Christina Ricci in "Pecker." You

know, really, I can go through each movie, and they said, `I'm not

wearing'--and Divine would always--and Van, this is how--he was so good with

talent. He would say, `Shut up. You're wearing it.' And they didn't know

what to say.

GROSS: John Waters will be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR.

I'm Terry Gross back with John Waters, the independent filmmaker who made his

reputation as the king of bad taste with his 1972 film, "Pink Flamingos." His

1988 film, "Hairspray," was adapted into the hit Broadway musical. He's put

together a CD of his favorite love songs called "A Date with John Waters."

Let's pick up where we left off.

So you said earlier that when you were young, you got your idea of romantic

sophistication from movies, particularly Douglas Sirk's movies. What other

movies really kind of helped you develop...

Mr. WATERS: Certainly....

GROSS: ...your idea of what romantic love was like?

Mr. WATERS: Well, I don't say they developed it in a healthy way, but

certainly "Peyton Place," "The Bramble Bush," those kind of movies, "The

Carpetbaggers," anything that Tennessee Williams wrote was really a huge, huge

influence on me, certainly. Even the movies they made of his where they took

out all of the good parts and had to change it. So certainly I was always

impressed by doomed love, and that's what most movies were about. Melodrama

is always about that. So I think mental health is later in life realizing

that you don't want that in your life. Basically if you can see that--I

believe that John Money, who was a sexologist, a very famous one in Baltimore

who died recently, he coined the phrase "Love Maps." That everybody has a type

and you're going to continue to go at that type for the rest of your life.

But if that type brings you pain, all your mental health is you can see it

coming and you decide whether you want that pain or you avoid it. I don't

think anybody completely changes. I think that you learn to make peace with

your neurosis, and certainly you learn how to deal with them and don't let

them make you unhappy.

GROSS: Is yours...

Mr. WATERS: That's my mental health.

GROSS: Is there a certain type that you've learned not to fall for?

Mr. WATERS: Well, anybody that says to me they want to go to a premiere with

me is a bad date, basically. You know, the kind I love is when they say,

`I've never really seen some of your movies.' That's like--that's great

romance to me. I can fall in love then because then they, you know, they

don't want to be in the movie, they don't want to go to a premiere with you.

I mean, going to a premiere is work. I usually think that being "plus one" in

that situation is fairly uncomfortable evening. And for me, I have to worry

if that person is having fun or not or they're feeling left alone. Or, you

know, the photographers sometimes yell, `Date, step out,' which is really

rude, if they're not famous. Or sometimes they yell if I'm with somebody

younger than me, `Is that your son, John?' And I always say, `Yeah, it is.

Yeah.' Just say anything, I don't care. But when I've heard them say that,

`Date, step out,' God, talk about rude.

GROSS: Well, I've been choosing the records. It's your turn. I want you to

choose something from "A Date with John Waters."

Mr. WATERS: Well, to me, you know--let me think, something--hmm. I'm trying

to think of one that is underplayed on the album, certainly. How about

Clarence Frogman--no, how about--I know one. I think one that would be great

on this show, because it's the most upbeat one, it's the most crazy one to me.

It's called "If I Knew You Were Coming I'd Have Baked a Cake." And that is

what I feel like. The next morning, if you're with somebody and you had a

great night and everything, and you get up in the morning. And it's like an

insane woman in 1950 if she knew later that she was having an affair and

somebody really cute was coming over, and she has to make food because she's

too nervous to be around the kitchen. And that's what it sounds like. So I

really like this song. And I've read a lot about the woman who sings it,

Eileen Barton, who I knew nothing about. And for a while on YouTube there is

an old really--and I found this out way after I picked her to be on the

album--a great shot of her in very early television, like a kinescope

lip-syncing the song while she makes a cake with two children behind her. And

she only died last year. And, of course, like all the stars from this era,

she claimed she never got one penny for the song or anything, which is always

very, very sad. But, hey, I bought the record in the right way, so I didn't

rip her off.

But I just wish sometimes--a lot of these singers that I picked on the song, I

did research on them afterwards and thought they all just died within the last

year or two. And so I kind of wished I had met them. But at the same time,

Eileen Barton might have thought, `Well, who is John Waters?' And then google

me and think, `Oh, my God! The last person I want my record associated with.'

GROSS: Well, I'm glad you explained why you chose her because I was going to

ask you, because it seems like, `What is this album--what is this track doing

on here?' So now we know. Let's hear it. This is Eileen Barton singing "If I

Knew You Were Coming I'd Have Baked a Cake.'

(Soundbite from "If I Knew You Were Coming I'd Have Baked a Cake")

(Soundbite of knocking)

Ms. EILEEN BARTON: Come in. Well, well, well, look who's here I haven't

seen you in many a year.

(Singing) "If I knew you were coming, I'd have baked a cake, baked a cake,

baked a cake. If I knew you were coming, I'd have baked a cake. Ha-chi-do,

ha-chi-do, ha-chi-do. Had you dropped me a letter, I'd have hired a band,

brand-new band in the land. Had you dropped me a letter, I'd a hired a band

and spread the welcome mat for you. Oh, I don't know where you came from

'cause I don't know where you've been. But it really doesn't matter, grab a

chair and fill your platter and dig, dig, dig right in. If I knew you were

coming, I'd have baked a cake..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's music from John Waters' new CD, "A Date with John Waters,"

which is a collection of love songs that he's chosen.

John, I always knew that song because like my mother always used to hum it and

sing it a little bit.

Mr. WATERS: Yeah, well, you won't...

GROSS: But I'm sure I'd never heard the original before.

Mr. WATERS: But I bet that you will hum that song accidently later today

after hearing it. You can't get it out of your head. And that's what makes a

hit really. And I believe this is probably from the same genre that was

Rosemary Clooney, "Come On To My House, Come On, Come On." It seems like that

kind of song, which is peppy and crazy and so wholesome that she might just

spontaneously combust in the kitchen and just splatter all over the wall.

GROSS: One of the current developments in your life is that the film musical

adaptation of the Broadway musical adaptation of your movie "Hairspray" is...

Mr. WATERS: Yep, is coming this summer. Yeah.

GROSS: ...is coming this summer with John Travolta in the role of the mother

that Divine originated and Harvey Fierstein played on Broadway.

Mr. WATERS: Yeah.

GROSS: So it's kind of like "The Producers," in a sense, that like the movie

inspired the Broadway musical, which inspired a musical based on...

Mr. WATERS: Well, it's different though.

GROSS: How is it different, yeah?

Mr. WATERS: And here's why I think it's different, because the movie of "The

Producers" was very much the exact play of "The Producers."

GROSS: Right.

Mr. WATERS: For this to work, it had to be reinvented again. Which I've

only read the script, and it seems like it had to be. The Broadway musical

reinvented my original movie, and I think the new movie of "Hairspray" has to

reimagine and reinvent the musical, which I think it has. I was on the set.

I'm in it. I play the flasher, of course. And I was shot with Mr. Travolta

in the trailer as he got into drag, which was--the experience is not that

different from Harvey or Divine doing it. It's still a long process. I have

high hopes for it. Who knows? I don't know what it's going to be like, but

"Cry Baby" is coming to Broadway now, so you never know what's going to happen

to them. They seem to at least--my films last. None of them are giant hits

when they come out, but they're like, in publishing what they call a "back

list." They stay in print. They're in boxed sets. They come out in every

country. They're rereleased. And you just can't get rid of them.

GROSS: Have you had no involvement in the screen adaptation outside of being

in it?

Mr. WATERS: Well, certainly they asked me to call John Travolta to talk him

into it, which I did. I certainly...

GROSS: What did you tell him? What did you tell him?

Mr. WATERS: Well, I just talked to him about the role, how basically it was

a role that both Divine and Harvey did as a person, very much as a character

role. Because Divine said the thing at the very beginning, that was true, `No

one can call me a drag queen. What drag queen would allow themselves to look

like this?' basically. It's an anti-drag queen drag role, basically.

GROSS: Like a frumpy homemaker.

Mr. WATERS: So, yeah, exactly. I mean, the first day on the set, when

Divine was dressed like that, I didn't recognize him. And the real housewives

in the community were saying, `Hi, do you believe they're making a movie?'

Talking to him, they just thought he was one of them. They didn't even

recognize him. So I think that--and John Travolta talked about how he grew up

in New Jersey, so he was younger than me, but his sister was my age and wore a

beehive. And we're from a similar community of East Baltimore, where this

was, so I think he understood it. And he was great. He was a funny guy on

the phone, that's all.

And New Line wanted me, certainly I showed Adam Shankman, the director. I had

meetings with all the people that were doing the costumes, the makeup. And

they came to Baltimore, and I showed them all the neighborhoods, I gave them a

tour. And so I've been involved that way from the very beginning with the

producers and everything, but I didn't want to write it. I made that movie.

I made that movie already, and I'm proud of it. And I was involved in the

musical. And I hope this is a big hit.

GROSS: Now, you live in Baltimore, and that's where "Hairspray" is set. And,

you know, I know you probably have other places, too, but you're still partly

based in Baltimore.

Mr. WATERS: No, I'm complete. My house, my office, everything is there. My

inspiration is there.

GROSS: Yeah, and now, you know, Baltimore for the past few years has been

home of the HBO series, "The Wire." And I was wondering if you've ever, you

know, go on the set or if you're interested in the series or anything?

Mr. WATERS: Well, certainly I think it's the best show on television.

Certainly many of the people that started with me are the main people in that

show. Vincent Peranio, who built a trailer for "Pink Flamingos" for 100 bucks

is the production designer of that show. Pat Moran, who has cast me from the

very beginning, cast the show.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. WATERS: She won the Emmy for "Homicide." Most of the crew has worked

with me. So, yeah, I know everybody on the show. I'm friends with David

Simon. I think it's a great, great show. And the only person I have to argue

with sometimes is the mayor, who is now the governor, who always is worried

about the image of Baltimore from the show. And I always tell him, `When I'm

away and I see those crack houses, I'm home sick. You know, not everyone

likes tall ships. I hate tall ships.' So, you know, not everybody wants to

come. Think of it, everybody that Barry Levinson has made movies about,

anti-Semitism, aluminum, you know, home improvement rip-off salesmen. I've

made movies about killer housewives. The television shows are about junkies.

But everybody likes the extremes of Baltimore. That seems to be what's

interesting, all creative people about the city, because it is an extreme city

but in a good way. It doesn't care about anybody else. It can't imagine why

you would want to leave. People say, `Oh, they're moving to New York.' And

people would say, `Why?' They're amazed by that, which I think is kind of

great and touching. And we have managed to embrace the things that many

cities, chamber of commerces use to hide. And we've embraced them with humor,

and I think that's why the city is such a good place to live.

GROSS: Well, I want to close with another track from your CD compilation "A

Date with John Waters," and I thought we could choose the opening track, which

is by far the sweetest. And...

Mr. WATERS: It's scary, those...(unintelligible).

GROSS: ...and it's Patience and Prudence singing "Tonight You Belong to Me."

Tell us why you chose it.

Mr. WATERS: Well, I chose it because it was the first record I ever

shoplifted, which is always a personal magic memory. But at the same time, I

think they're scary almost. They're almost like--I loved Rhoda Penmark in

"The Bad Seed" as a child, and this is kind of my visualization of them, or

also Damien or any of these "Children of the Damned," any of these singers.

And they are so sweet and they're singing a song called "Tonight You Belong to

Me," which is a little inappropriate for a child song. I've read later that

they were very angry that their father was, I think, owned the record company

and he couldn't let them go on "Ed Sullivan." And when I was doing a signing

in LA, one of them said that Prudence still lives in LA and is bitter. So I

don't know what that means, but I hope that if--Prudence, if you're

living--you've been a huge influence on me. It was the first song I ever

taught my little sister. I used to play when she was a baby, the first music

she ever responded to. So it's been a song that's been in my life for very

early memories, and I've always had great ones about it.

GROSS: John Waters, it's really great to talk with you, again.

Mr. WATERS: Thank you.

GROSS: John Waters' new CD of love songs is called "A Date with John Waters."

(Soundbite from "Tonight You Belong to Me")

PATIENCE AND PRUDENCE: (Singing) "I know you..."

Unidentified Backup Singers: (Singing) "I know..."

PATIENCE AND PRUDENCE: (Singing) "...belong to somebody new, but tonight you

belong to me. Although..."

Backup Singers: (Singing) "Although..."

PATIENCE AND PRUDENCE: (Singing) "...we're apart, you're part of my heart,

and tonight you belong to me. Way down by the stream, how sweet it will seem,

once more just to dream in the moonlight. I know..."

Backup Singers: (Singing) "I know..."

(End of soundbite)

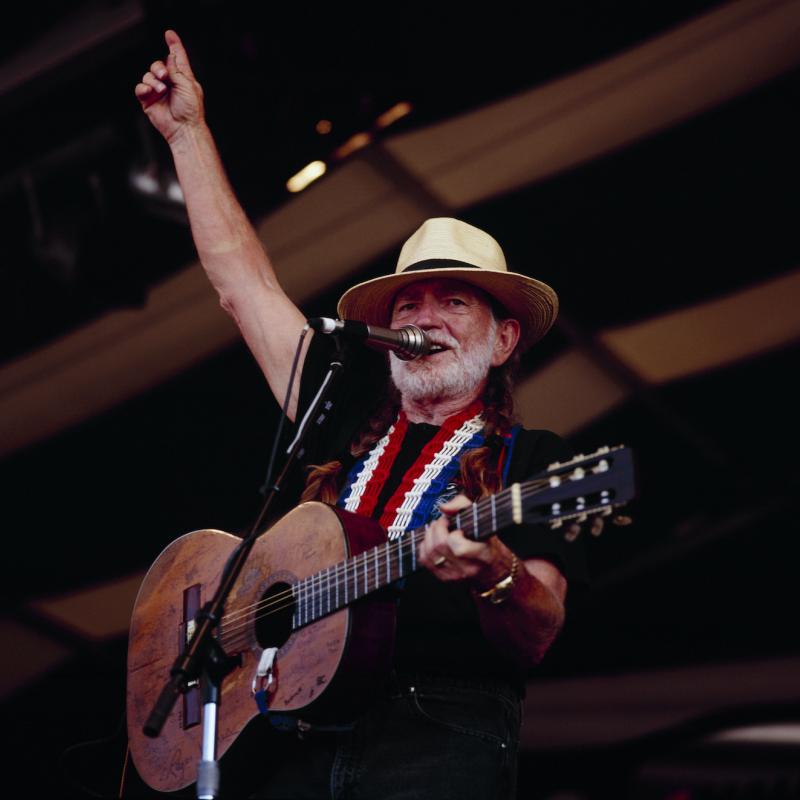

GROSS: Coming up on this Valentine's Day, Willie Nelson talks about writing

two songs about heartbreak.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Willie Nelson describes writing two of his songs

TERRY GROSS, host:

Valentine's Day is a time to celebrate love or wallow in heartbreak. So for

those of you obsessing with what went wrong, we have two songs about

heartbreak, and Willie Nelson is going to tell us about writing them. Here he

is on a 1961 demo recording, doing his song, "Opportunity to Cry."

(Soundbite from "Opportunity to Cry" by Willie Nelson)

Mr. WILLIE NELSON: (Singing) "Just watch the sun rise on the other side of

town. Once more I've waited and once more you've let me down. This would be

a perfect time for me to die. I'd like to take this opportunity to cry. You

gave your word, now I'll return it to you with this suggestion as to what you

can do. Just exchange the words `I love you' to `Goodbye' while I take this

opportunity to cry. I'd like to see you but I'm afraid that I..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Willie Nelson and a demo recording he made of his own song in

1961 when he was trying to interest people in recording his songs.

What was the fate of that song? Did anybody ever do it?

Mr. NELSON: I don't think everybody--anybody done it but me. I've recorded

it maybe a couple of times since then on, you know, various, a couple

different albums. I don't remember what they were right at the moment, but it

was one of those really sad, almost pitiful songs.

GROSS: You know, in talking about country songs, like country songs have

certain conventions in a way. You know, a lot of country songs are about

cheating or drinking too much or falling in love. I guess you could say the

same thing about rock songs, but there's also like a subcategory of country

songs where like you're feeling so bad, you're just overwhelmed with

self-pity, and one of the most self-pitying of the self-pitying songs is a

song that you wrote that's included on your demo sessions that I really want

to play and hear the story behind, and so here it comes. This is Willie

Nelson singing a very self-pitying song.

(Soundbite from a Willie Nelson song)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "If I only had one arm to hold you, better yet, if I

had none at all. Then I wouldn't have two arms that ached for you. And

there'd be one less memory to recall. If I'd only had one ear..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: And then in the next verse, you imagine having only one eye, so you'd

have only one eye to cry. Did you think...

Mr. NELSON: That's pitiful, isn't it?

GROSS: Yes, so self-pitying. Did you think that, when you sat down to write

this, that you would write the ultimate self-pitying song?

Mr. NELSON: Actually, I didn't sit down to write that one. The way that

song happened, I was lying in bed with Shirley, and I woke up in the middle of

the night wanting a cigarette and her head was on my arm, so I had to reach

over on the side of the bed and get a cigarette and put it in my mouth, and

then get a match with that one hand and then try to strike that one match. So

it all started from that.

GROSS: Oh, because you only had one arm. Really? Is this really what

happened?

Mr. NELSON: It's true. That's a true story. And so from the one arm, I

went into the one eye, one ear, one leg.

GROSS: That's really funny.

That was an excerpt of our 2006 interview with Willie Nelson.

(Soundbite from a Willie Nelson song)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "And if I had been born with but one eye, then I'd

only have one eye to cry. And if half of my heart turned ashes, maybe half of

my heartaches would die. If I'd only had one leg to stand on, then a much

truer picture she'd see. Because then I more closely resemble the half a man

she made me. The half a man she made of me."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Coming up, Valentine's Day cards. Our linguist Geoff Nunberg has been

thinking about why we still send them.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Linguist Geoff Nunberg describes the connection

between postal system and Valentine's Day

TERRY GROSS, host:

Even in the age of e-mail, if you were fortunate enough to receive a Valentine

today, odds are it was written on paper rather than in pixels. In fact, as

our linguist Geoff Nunberg observes, the history of Valentine's Day as an

American holiday has always been intimately connected with our postal system.

Mr. GEOFF NUNBERG: When a new communication system is introduced, it can

take a while to grasp its implications. When Thomas Edison invented his

improved telephone receiver in 1877, he thought it would become a medium for

broadcasting concerts and plays to remote auditoriums. For 25 years after

radio was developed at the end of the 19th century, people chiefly regarded it

as a means of ship-to-shore communication.

And then there's the US postal system. For the first half century of its

founding, its main function was to circulate newspapers to a national

audience. Not that you couldn't send letters, too, but the rates were much

higher than for periodicals. In 1840, sending a letter from Boston to

Richmond cost 25 cents a sheet, at a time when the average laborer made 75

cents a day. In fact, the postal inspectors were always on the lookout for

people who sent each other newspapers at the cheaper rate and added coded

personal messages by putting pin pricks in certain letters.

That all changed in 1845 when Congress enacted the first in a series of laws

that sharply reduced the cost of sending letters. The new rates led to a vast

surge in personal correspondence. They set up a communications revolution

that the historian David Henkin has chronicled in an engaging new book called

"The Postal Age." The cheaper postage didn't simply enable Americans to keep

in touch with one another, in what was becoming the most mobile society on

earth. It was also used by businesses who made mass mailings of circulars and

by swindlers who sent out letters promoting get-rich-quick schemes. People

sent each other portraits of themselves made with a recently developed

daguerreotype process. They sent seeds and sprigs to distance friends and

family eager for the smells of home. And, oh, yes, they also sent

Valentine's.

St. Valentine's Day was an ancient European holiday, of course. Back in

England, people drew lots to divine their future mates and exchange love notes

and poetry. But before the 1840s, Puritan Americans almost completely

disregarded the holiday, like the other saints days of the old world. But the

drop in postal rates set off what contemporaries described as a Valentine

mania. By the late 1850s, Americans were buying three million ready-made

Valentine's every year, paying anything from a penny to several hundred

dollars for elaborate affairs adorned with gold rings or precious stones.

People sent cards to numerous objects of their affection, often taking

advantage of the possibilities for anonymity that the mail provided.

That was alarming to moralists who worried that the postal system in general

promoted promiscuity, illicit assignations and the distribution of

pornography. Actually, they weren't entirely wrong about that.

But fully half of the Valentine's traffic consisted of comic or insulting

cards that people sent anonymously to annoying neighbors or unpopular school

masters. By the time the Valentine craze tapered off a few decades later,

people were sending each other cards for Christmas, Easter and on their

birthdays, as the greeting card became a fixture of American life.

In a lot of ways, the development of e-mails has followed the same course that

the postal system did. For one thing, the implications of the new system

weren't clearly understood at first. The first e-mail software was designed

for sending files and programs over a network. And once e-mail and other

forms of electronic communication became widely available, they were rapidly

adapted to almost all the purposes that cheap mail had served. E-mail has

ushered in a new age of personal correspondence, but it's also facilitated

swindles, junk mail, pornography and anonymous hookups and erotic connections.

In short, e-mail is used for just about everything that delighted and trouble

people about the postal system in the mid-19th century.

But following on the heels of cheap long distance rates, e-mail puts a final

kibosh on the personal letter. Nowadays the only personal messages that most

people will regularly go to the trouble of putting in the post are the ones

that serve a ritual function, like thank-you notes, letters of condolence or

greeting cards. True, you can send a Valentine electronically, and some sites

will even allow you to do it anonymously, though you might want to think long

and hard about plighting your troth to anybody stupid enough to open the

attachment on an anonymous e-mail.

But for most of us, those kinds of messages can't do their magical work if

they don't physically originate with a sender. It's like getting an

electronic postcard from friends who are visiting Turkey, it may be nice to

hear from them but you're not going to print it out and stick it up on your

refrigerator door. Those remaining postal rituals are a vestigial sign of the

allure that letters once exerted on the American imagination. In fact, letter

is about the only word for correspondence that has resisted digitization. We

talk about e-mail and electronic notes and messages, but sending somebody a

letter still means putting a piece of paper in an envelope.

It's true that nowadays the only pieces of paper we can expect to find in our

mailbox that still bear a handwritten signature were generally printed by

Hallmark. But maybe it's appropriate that the cards that signal the opening

of the postal age should be among its last remnants as it draws to a close.

GROSS: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist who teaches at the school of information

at the University of California at Berkeley. His recent book on the language

of politics is called "Talking Right."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.