The "Two Nations of Black America."

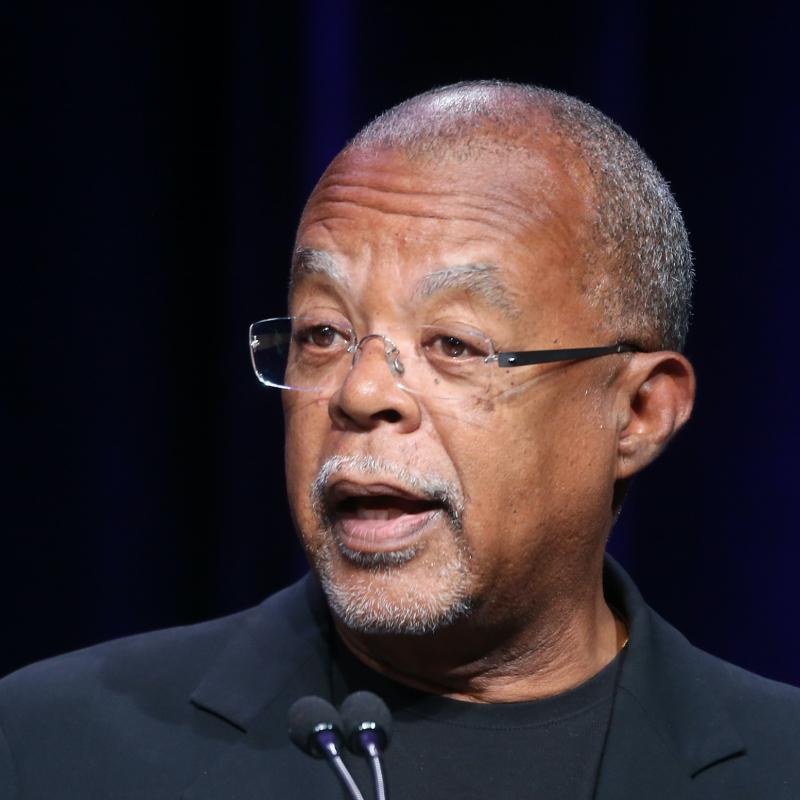

Frontline correspondent and Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Gates hosts a Frontline segment called "Two Nations of Black America" which airs Tuesday night on PBS. Today, America has the largest black middle class in its history, yet half of all black children are born into poverty. (Interview by Barbara Bogaev)

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on February 9, 1998

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 09, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 020901 NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Two Nations of Black America

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

BARBARA BOGAEV, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev sitting in for Terry Gross.

One-third of all black Americans working full-time live below the poverty line. And the economic gap between the rich and the poor is growing more rapidly in the black community than it is in the white community.

The implications of this rift for the black middle class is the topic of a Frontline documentary, airing tomorrow night on public television stations nationwide. It's hosted by Henry Louis Gates. He is the W.E.B. DuBois Professor of Humanities at Harvard and the chair of its Afro-American Studies Department.

In the program, Gates examines affirmative action, in part by telling his own personal story -- how a young black child from a poor family in Piedmont, West Virginia ended up a member of the intellectual elite.

HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR., W.E.B. DUBOIS PROFESSOR OF HUMANITIES, CHAIR, DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES, HARVARD UNIVERSITY: Well, I entered Yale in 1969, with the largest group of black people that had ever gone to Yale. The class of 1966 at Yale had six black men to graduate. The class that entered with me in 1969 -- we were members of the class of '73 -- had 96 black people. I mean, that was remarkable.

And what -- how did we get there? I mean did all of a sudden, Yale found 90 smart black people who didn't exist in 1966? Of course not. I mean, we were the affirmative action generation. We were the first large group of black people to hit the Ivy League campuses in that year, September of 1969.

That was my generation. That was my experience.

BOGAEV: Why did you revisit this story in your personal history for a documentary about the growing rift between the black middle class and the black underclass?

GATES: Well, as many people have said -- it's a cliche by now -- but it's the best of times and it's the worst of times for the African-American community. We have the largest black middle class in our history, but simultaneously, 45 percent of all black children live at or beneath the poverty line.

And no one -- no one predicted this outcome in the 1960s. I don't care if they were left or right. I don't care if they were black nationalists or socialists. How did we get there? And the only way to figure out how we got there from -- it seems to me, was to go back and to trace that affirmative action generation that hit the historically white schools in the late 1960s.

BOGAEV: What lesson do you draw from your own experience that's relevant to the -- to the issues facing black leaders today?

GATES: Well, it seems to me that affirmative action was -- has been an enormously positive influence in American society. The reason that the black middle class is so much bigger today than it was the year that Dr. King was assassinated, for example, is directly traceable to affirmative action. But what's happened is that the size of the black middle class has become static, almost frozen. It's not growing like we expected it to grow.

The society decided to allow some of us into the middle class, and then to shut those doors. So that we have two self-perpetuating classes within the black community: a black middle class that's larger than it's ever been, but not large enough; and this ongoing, horribly suffering black underclass. And what I'm hoping -- what many of us are hoping -- is that we can adopt a form of affirmative action that will be focused on the class differentials in America generally, and more specifically the class differentials within the African-American community.

In other words, we have to change the shape of the bell curve of class.

BOGAEV: How do you explain, then, the accelerating economic disparity and -- and emotional disparity, I suppose -- or psychological or existential disparity is what you're talking about -- between those who've benefited from affirmative action, those who've made it, and a black underclass? Does it mean that the civil rights movement has failed?

GATES: I think the civil rights movement has achieved all that it could possibly achieve, given the level of its analysis. You see, for 100 years, we thought that the most important problem facing members of the African-American community was white racism. We didn't think primarily about economic relationships. We thought about almost a primal xenophobia in the white American community. They saw a black face; they would hate that person. They would find that person ugly. They would try to punish that person. They would try to delimit the possibilities of that person.

The primary cause of our oppression was race. Whereas in fact, though it took a century between slavery and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 to achieve this -- though in fact once we could get rid of de jure segregation, the number of black people who could enter the middle class turned out to be surprisingly large, and their moving into the middle class went surprisingly quickly.

But the argument of the civil rights establishment was that all of us would plunge head-long into the middle class. And that was naive. It never was going to happen. Marcuse (ph), the philosopher -- Angela Davis' professor -- predicted this in 1958. And no one believed him. I mean, he said the civil rights movement will create a new black middle class. That will be its primary effect.

Well in 1958, that seemed like a big deal, and in retrospect, it was a big deal. I mean, don't get me wrong. The fact that we have such a large black middle class compared to the black middle class before 1968 is a wonderful thing. My concern is that that class is not growing, and the size of the black underclass is growing.

BOGAEV: How has the civil rights movement changed to accommodate this -- this growing economic disparity in the black community?

GATES: I don't think any of us knows what to do about it. I don't think that there is a realistic or effective analysis floating out there that accounts for this disparity within the African-American community. And I don't think that even many of my friends who are staunch proponents of affirmative action like I am -- I don't think that they know what to do about the class gap within the black community. That is our primary problem today.

Our primary problem is not white racism, as awful as white racism continues to be. It is our inability to figure out how to expand the size of the black middle class; how to affect both structurally and behaviorally the causes of poverty that are punishing so many people of color in this country.

And I think that many of us have been reluctant to say that the causes of poverty are both structural and behavioral, meaning there are systematic things that -- meaning that there are systemic things that we have to do, but meaning also that -- simultaneously that we need a moral revolution within the African-American community.

There are certain forms of behavior that we have to find unacceptable and intolerable within our community. There's no -- absolutely no reason for people to have dysfunctional families to the extent that African-Americans have. The out-of-wedlock birthrate is horribly high. We have to do something about that. We have to demand that each member of the black community assume responsibility for her behavior or his behavior.

We have to be firm about these things. But at the same time, lest I sound like some right-wing conservative, we have to insist that there are job opportunities opened up for every person in this country who is seriously seeking a job; has the skills for a job; and is determined to meet the requirements of the workplace.

And that is a situation which does not exist in this country today.

BOGAEV: Now, critics of affirmative action come in and respond that the '60s were all about breaking down the barriers of race, but now it's all about class. What you're saying is all about class. How -- where does that leave the race issue in affirmative action? Why have affirmative action based on skin color if we've moved into a class debate?

GATES: Well, I think that that's the question that we all have to begin to ask ourselves. I mean: should my children benefit from affirmative action? And if so, why? And if not, why not? I mean, this is a serious question. My children will probably be very successful individuals.

I mean, I would hope. They're very well educated. They're highly motivated. They come from a middle class home. Should they benefit from affirmative action in the same way, let's say, that I benefited from affirmative action as a working class person from Appalachia? Or should they benefit from affirmative action in the same way that some of their friends who live in the inner city, say, in Roxbury here in Boston benefit?

These are questions that we have to begin to ask ourselves. I tend to be much more sympathetic toward an affirmative action that includes, as one of its principles or premises, the matter of scarcity or economic relationship or class. Use whatever term that you want. But there will come a point when the black middle class will escape the necessity or escape the need for affirmative action breaks. The question is: have we arrived there yet? Probably not.

I tend to think that we need three generations of affirmative action benefit to make the -- make solid the perpetuation of middle class status. But when will that -- when will that third generation manifest itself? Am I the first generation? Am I the second generation? Are my daughters the third generation? And then, what do you do then?

Well, I am concerned that we cannot survive as a community, to use that metaphor, unless the size of the middle class within the African- American people increases. And the only way that it can increase is through affirmative action.

BOGAEV: My guest is Henry Louis Gates, Jr. He's the DuBois Professor of the Humanities and the chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Harvard University.

Tomorrow night, he hosts a PBS Frontline documentary that measures the success of the civil rights movement. It's called "The Two Nations of Black America." We're going to take a break for a minute, and then we'll talk some more.

This is FRESH AIR.

If you're just joining us, my guest is Harvard University Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. He serves as a correspondent for the PBS series Frontline. Tomorrow night on Frontline, he hosts a documentary on the rift in the black community between the black middle class and the black poor. The show is titled The Two Nations of Black America.

You explore a number of issues of identity in the Frontline piece -- both the identity of -- the idea of the monolith of the black community as a whole, and also personal identity. And you pose an interesting question to Cornell West. He's a philosopher and a professor at Harvard. You ask what it means to be black now as opposed to what it meant to be black in the '60s. How did he answer?

GATES: He said that we had a much more unified community in 1967 than we do today. We have much more fragmentation; much more nihilism; much more despair. You see, we were united by -- we were united by white racism, as terrible as that might sound. But we were. You see, we had a common enemy and the enemy was clear. If we could just get rid of George Wallace and Orville Faubus and Bull Connors, everything would -- would be better. We could reach the promised land.

The problem is that we did. The problem is that we did get rid of those symbols of -- and -- of de jure segregation and of de jure segregation itself. And what was the result? Well, what was the result was that some of us entered the middle class and a lot of us stayed behind. We had spent 100 years trying to get rid of legal segregation, and we thought that once we did, all of our problems would be solved, and that is because of our own failures of analysis of the complexities of the American system.

And we confused what turns out to have been class distinctions or class differentials or class suppression with racial oppression. We -- and we missed the boat, I think, by that confusion or because of that confusion. And many of us now are trying to do something about it. I don't think anyone seriously wants a socialist revolution or believes that that's even possible.

The question becomes: how can we redistribute wealth in this country in such a way to diminish the size of the underclass black and white? That is the moral and political problem, I think, confronting our generation of African-American intellectuals.

BOGAEV: I find it really interesting that you -- you say in the program that you feel alienated from the people that you're trying to reach out to -- a young, urban, black culture. And you mention gangster rap -- that that, in particular, just confounds you. And it just occurred to me that every middle-aged person feels alienated from the popular culture of young people, whether it's music or their social -- their social habits and their social context.

GATES: Our parents were alienated from us. I remember when I grew an afro -- my father, particularly my uncle, thought it was the ugliest thing that he had ever seen. They thought all of our romantic notions about Africa and about black identity were just total rubbish. They thought the race was falling apart.

So I think that the generation alienation is part and parcel of the African-American experience like every other experience. I don't think that that's new. But I think that the -- what I feel alienated from is not the younger generation of African-American people. After all, I make my living teaching the younger generation, and younger generations, whether they're black or white. And I'm very close to my students, black and white.

I don't feel that form of alienation. I feel a form of alienation from a certain lifestyle. And it's a lifestyle that is so counter, so opposed to the values that the members of my community shared when I was that age, and continued to share beyond, through my college years. That we believed in the future; we believed in ourselves as a people; we thought that things would get better. And they -- we thought that they would get better if we worked together.

And we -- we had hope. We cherished hope. As Cornell says in his latest book "Restoring Hope," our challenge is how to restore the hope that we enjoyed, that we experienced as members of the African-American community in the 1950s and 1960s, and throughout much of the 1970s. The depth of despair is shocking.

It is the depth of alienation. It is the depth of fragmentation within the black community that frightens me; that alienates me; that makes me wonder: what does a gangster lifestyle have to do with the African-American experience that I love, that I cherish, and indeed that I teach and write about?

Where did this come from? What's it a symbol of? What's it a function of? And, what do we do about it? That's what worries me. There is clearly a difference between the fabric of African-American society and faith and hope and belief structures of the 1960s and those same things today. And that's worrisome.

BOGAEV: Well, one conclusion of the Frontline program is that we -- meaning America -- needs the same kind of interracial coalition that was at the center of the civil rights movement 30 years ago. And one of your commentators, the urban sociologist William Julius Wilson (ph), says in response to that, that that will be very difficult because people of different races are even more divided than they were in the '60s now. They're even less able or less willing to work together than back then.

Do you think that's true? And why, if the real problem is class, is it true?

GATES: Well I think that it's -- boy, that's a tough one. The -- the historic liberal coalition, of course, has fallen apart -- between blacks and liberal Jewish people and liberal members of the WASP community et cetera, et cetera; become fissured. There was an old joke in West Virginia that there were so many political splinters in the Democratic Party they didn't have factions -- they had fractions. And we have a fractionated liberal coalition, I think -- or the remnants of that coalition.

And we have to figure out how to put it back together, because the problems are beyond race or religion or one -- the interests of one group. We have to figure out -- just like a successful marriage -- I mean, we have to figure out common ground.

We have to figure out ways to disagree about issues where we can't produce a consensus and identify what the problems are that are afflicting the society, like unemployment; like poverty. And then, adopt a common program toward addressing those problems.

But we can't do it from the safety of our little ghettos, whether they're religious ghettos, or ethnic ghettos, or gender-based ghettos. We have to figure out a way to agree to disagree and to re-forge those coalitions. And many of us are trying to do that, without a doubt.

Many of us are working hard to re-cement the relationships between the liberal Jewish community and the African-American civil rights leadership. And that, of course, fell apart because of affirmative action, by and large. And we need to figure out ways to put that back together.

BOGAEV: You teach young people at Harvard. Do you have people -- students -- coming to you and saying, grappling with the same issues that you raise in this program? Who am I? What's my responsibility to people who haven't made it? What does it mean to be black now, in 1998?

GATES: Oh, every day. I mean, the degree of guilt about one's own individual -- the degree of guilt about one's individual success at a place like Harvard is enormous. And so what I tell them, and I think what my colleagues tell them, is that the most important thing you can do for the black community -- the blackest thing that you can do -- is to be successful. Bust the books. Get straight As. Go to law school if that's what you want to do. Become a professor if that's what you want to do. That is a fundamental part of the African-American experience.

I read a poll recently. It was a Gallup Poll of inner-city black kids. And it said, basically, I'm paraphrasing here, but "list things white." And on that list included the following: getting straight A's; speaking standard English; visiting the Smithsonian Institution. Now, if anyone had said anything like that when I was growing up, first of all, your mother would have beat your behind and then secondly they would have checked you into a mental institution.

I mean, this is alarming that these things -- that success, individual success, would be identified as something white -- that is, alien to the African-American community. That is sad. And that is worrisome. We've internalized racist stereotypes of -- about ourselves. And we have to fight, as leaders of the African-American community, against this internalization process; against those stereotypes which many of us live out every day.

BOGAEV: Henry Louis Gates, I really want to thank you very much for talking today on FRESH AIR.

GATES: Well, thank you. Thank you very much for having me.

BOGAEV: Henry Louis Gates is the W.E.B. DuBois Professor of Humanities at Harvard. He hosts the Frontline documentary, The Two Nations of Black America, tomorrow night on public television stations nationwide.

I'm Barbara Bogaev and this is FRESH AIR.

Dateline: Barbara Bogaev

Guest: Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

High: Frontline correspondent and Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Gates hosts a Frontline segment called "Two Nations of Black America" which airs Tuesday night on PBS. Today, America has the largest black middle class in its history, yet half of all black children are born into poverty.

Spec: Race Relations; Business; Economy; Politics; Government; Poverty; African-Americans

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Two Nations of Black America

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 09, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 020902NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Thalidomide Comeback

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:30

BARBARA BOGAEV, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev, sitting in for Terry Gross.

In the late 1950s and early '60s, the drug thalidomide was widely prescribed to pregnant women in Europe, Japan, Australia, and Canada as a treatment for morning sickness. The 12,000 babies born to these women had tragic birth defects, including malformed and missing limbs, brain damage, and internal injuries.

Thalidomide was banned in 1961 in most countries, but scientists continued to experiment with the drug as a powerful treatment for leprosy, cancer, blindness, and most recently AIDS. Now, the FDA is considering approving thalidomide for the first time in the United States.

My guest, Sheryl Gay Stolberg, says that no one is more worried about the return of thalidomide than the men and women who have suffered its side effects for the last 40 years -- the now-grown thalidomide babies.

Stolberg is a science reporter in the Washington bureau of the New York Times. She says that thalidomide was so toxic in utero that many women who took it miscarried.

SHERYL GAY STOLBERG, NEW YORK TIMES SCIENCE REPORTER: This drug is disastrously destructive in pregnancy. The tiniest amount, if taken during the right window of time -- or maybe the wrong window of time -- in early pregnancy, is just simply lethal to the fetus.

There is a certain window of days in early pregnancy where if you took even one dose of thalidomide, it simply interrupted whatever was developing at the time. So, if the legs were developing or the arms or the kidneys -- whatever organ -- if thalidomide was taken, it just simply wreaked havoc on the development of those organs.

BOGAEV: Twelve-thousand babies were born to women who took thalidomide during pregnancy in the late '50s and the early '60s. What was the effect on the babies born to those women? And you've outlined some of them. Why don't you give us a better idea of what the outcome was.

STOLBERG: Well, the effects were wide-ranging, honestly. First of all, some of those babies were never born. Some died. Some were born with massive internal injuries. Some were born with brain damage. But what most people remember of the thalidomide babies were those who were born with a condition -- a very rare condition known as fauxcomilia (ph) -- literally seal-flipper limbs.

And this is a condition in which the arms and legs are truncated, distorted. They look like seal flippers. And some of these babies were born with little more than heads and trunks. Some, like one of the -- the women that I met, were born with a -- she has arms that just -- are two hands, really, that extend from her shoulders; and tiny little feet attached to her hips, curled upward with, I think, seven or eight toes on each foot.

That's really what people remember of the thalidomide babies -- were the ones that were born so grossly deformed.

BOGAEV: The link between these birth defects and thalidomide was finally made in 1961. How quickly did the countries where thalidomide was available act?

STOLBERG: Well, Germany acted right away -- on the very same day that a West German newspaper featured an article about the German doctor who uncovered the link between thalidomide and birth defects. On that same day, West Germany pulled the drug off the market. Britain followed just a few days later. In Canada, however, the drug remained on the market until March of 1962 -- four months after the original discoveries were made.

BOGAEV: It's really an interesting history of thalidomide in the U.S. It was never marketed here. It wasn't approved here. Why did the FDA reject it way back when?

STOLBERG: Well, what happened was this. The drug had been allowed in pharmacies in West Germany and in other countries in Europe and elsewhere -- Australia and Japan. And one of the companies that held the license to market thalidomide, a company named Richardson-Merrill (ph), was trying to market it here in the United States; came to the FDA with an application for approval. And a very young FDA medical officer -- a Canadian by the name of Frances Kelsey (ph) -- held the approval up.

Now, she was very young at the time, and in fact she jokes now -- she's in her 80s now -- that the agency gave this to her 'cause it was an easy one. And she was brand new and they didn't want to give her anything too -- too difficult.

So, she held this application up because she was concerned about a side effect of the drug -- something that had evidenced itself in testing called peripheral neuropathy (ph); in essence, numbness or tingling of the hands and feet.

And Dr. Kelsey held up the approval of thalidomide for so long that the scandal erupted over birth defects while the application was still pending. And so, of course, it never got approved.

BOGAEV: Now thalidomide was banned, then, in the '60s. How and why did scientists continue to experiment with it? I mean, is that -- is that common that a drug is banned for one use, but is further researched?

STOLBERG: Well, what's interesting is that thalidomide was banned. Most people thought it simply went away. In fact, it was the sale of thalidomide that was banned, and not thalidomide itself. And so, samples remained and the drug company continued to manufacture it for experimental use.

And what happened was in the 1960s, in the mid-'60s, an Israeli doctor decided that he was going to give thalidomide to his leprosy patients because they were having trouble sleeping. And after all, thalidomide was a sedative.

He gave the drug to these patients and lo and behold their lesions cleared up -- almost overnight. Well, this was startling. And so soon, more inquiries took place; more study. And within 10 years, by 1975, thalidomide was considered the standard treatment for leprosy by the World Health Organization, and the Public Heath Service of the United States even began importing the drug from Germany for leprosy patients and distributing it with very strict controls out of a federal hospital for leprosy patients in Carville, Louisiana.

BOGAEV: So all these years, thalidomide has been -- has been, in a limited sense, available.

STOLBERG: That's true. It's been available in a very limited sense. Few people knew it. It wasn't advertised and there aren't that many leprosy patients around, at least not in the United States. And so, it was simply quietly distributed to those who needed it, under very strict government control. But it was now allowed in the pharmacies.

BOGAEV: The story broke, at least in the media, when people with HIV started -- started using it for a number of treatments. Was that what spurred the FDA to reconsider it, and reconsider it quickly?

STOLBERG: That is what spurred the FDA to reconsider it. What happened was this: in 1991, an immunologist by the name of Gila Caplan (ph) at Rockefeller University in New York began looking at thalidomide. She was an expert in leprosy. She is an expert in leprosy. And she was interested in how precisely thalidomide worked.

Well, what she found out was that thalidomide inhibited a crucial protein that helps regulate the body's immune response -- a protein called tuminocrosis (ph) factor alpha. Well, once she discovered this, the implications were enormous, because a drug that could help regulate the immune response could be useful for a wide variety of things: auto-immune diseases and graft versus host disease, in which people who get organ transplants reject those transplants; and of course AIDS, the most notorious disease of the immune system that we have.

And so, AIDS drug buyers clubs in New York and in San Francisco began importing the drug for patients. And they were going to Brazil to get the drug. Brazil had already licensed the drug for leprosy patients, and so it was readily available there. And the FDA, as it has throughout the AIDS epidemic, kind of looked the other way.

They -- they allowed the drug to be imported. They wouldn't allow it to be sold here, but there are rules governing the importing of drugs from other countries, and they -- they allowed this to go on all the while, you know, knowing that the drug was not allowed in American pharmacies.

And then after a time, it became clear to the agency that it was going to have to do something. The drug was being distributed through the black market and through AIDS drug buyers clubs. You could even buy it over the Internet. Then 60 Minutes broke a story about the birth of new thalidomide babies in Brazil, and suddenly the agency, I think, was feeling pressured about allowing too much of this drug into the states without proper regulation. They wanted to regulate it.

BOGAEV: Cheryl Gay Stolberg is my guest. She's a science reporter in the Washington bureau of the New York Times. We're talking about the return of thalidomide. We'll hear more after this break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Back with New York Times science reporter Sheryl Gay Stolberg. She's been covering the story of the controversial return of thalidomide.

Now, a number of parties are very worried about this new development -- about the resurgence of thalidomide. And obviously -- or the most obvious party are the babies -- now the grown victims of thalidomide. You write about one, Randy Warren, who's the founder and head of Thalidomide Victims Association of Canada. And his group's position -- their initial reaction to the news that thalidomide might again come on the marketplace, was: "we will never accept a world with thalidomide in it."

How -- how does he articulate, or how did he articulate, that position in the face of all its known uses? I mean, this sounds like a really good drug.

STOLBERG: Well, his -- that was his initial position. But over time, this group, the Thalidomide Victims of Canada, which is, I think, really an extraordinary group for what they've done. This group really took a hard look at themselves and at thalidomide and at its uses. And they came to a very subtle, I would say nuanced, position. And it was this: we will never accept a world with thalidomide in it. Meaning, we hate this drug. We don't want this drug to be in our world.

But at the same time, they recognize that the drug could help people -- thousands of people. And they felt that they, of all people, could not stand in the way of a drug that could help others, even if it was the very same drug that had maimed them. And so they -- and at the same time, they realized that this drug was coming back with or without them.

AIDS drug buyers clubs were already bringing it into this country. It could be sold on the Internet. And this, to them, was -- was really a prescription for danger and for disaster and for the birth of more thalidomide babies -- the thing that they really wanted to avoid more than anything.

So in the end, having the drug put back on the market with strict controls from the FDA became preferable to them than unfettered distribution on the black market.

BOGAEV: Randy Warren has a particularly -- I don't know if it's particularly harrowing, considering what other thalidomide victims have gone through -- but his sounds pretty torturous. I think he spent his first eight years of his life in the hospital?

STOLBERG: Yeah, he has a harrowing story, and at the same time it's a typical story, given what the thalidomide victims have gone through. He did spend the first eight years of his life in the hospital. He was born with arms that are two inches shorter than they should be, and with four fingers on each hand. He was born without thumbs. He has two stumps for legs, and they are attached to little feet that are kind of positioned awkwardly, such that they're really unusable as feet.

And he went through all kinds of surgeries; surgeries to correct ear deformities. He -- doctors actually severed his forefingers from his hands and repositioned them to create thumbs. They also tried to get him to fit into artificial limbs, which he really hated. And many of the thalidomide babies were pressed into wearing artificial limbs, and they all have rejected them, saying that they just -- they just didn't work for them.

Randy really carries around the burden of being deformed. He said to me once that it's not like you're handicapped or you're an amputee. He said you're deformed. It's different. People stare a lot. And I think life has been -- has been very difficult for him.

BOGAEV: But yet, Randy Warren is now, I guess you call him a consultant or adviser to Seljean (ph), the company that is looking to get a license of distribution of thalidomide.

STOLBERG: I wouldn't call him a consultant because that implies he's being paid for his work. I think what happened -- what happened was that Randy Warren wanted his voice heard. He decided that if the United States was going to bring thalidomide back, they were going to have to listen to him, and listen to his views. And he wanted to engage the drug company in discussions about this. He wanted to make sure that the drug company was doing everything it possibly could to keep this drug out of the hands of pregnant women.

And through that process, which began really as a very adversarial process, he developed kind of a bond with this drug company. The new company is called Seljean. And he -- he and the company realized that in a way they had similar goals. Certainly, the company did not want to be responsible for the births of any more thalidomide babies; nor did Warren.

And so when the company was drafting its materials for the distribution of thalidomide, they would run the materials by Warren. And they would say: "Randy, what do you think?" And for instance, in the warning labels, the initial warning that Seljean proposed said: "avoid pregnancy." Well, Warren thought that was all wrong. He wanted it to say: "do not get pregnant." And the company ultimately agreed.

BOGAEV: Other people have fears of thalidomide approval creating a slippery slope. For instance, doctors prescribing thalidomide for minor disorders or this specific company, Seljean, marketing the drug overseas in the third world. Are there precedents in recent history of that kind of behavior?

STOLBERG: Well, the company says it has no plan to market the drug overseas. As for prescribing it for minor disorders, you know, when a drug is approved in this country, a doctor can prescribe it for anything he or she wants. And that has always been the subtext with thalidomide. It's always been the big fear.

In fact, when thalidomide is approved, it will be approved not for AIDS, but for leprosy. But everyone knows that the big market for this drug is in AIDS. And so, most doctors who prescribe it will in fact be prescribing it for something other than its intended use.

Now, will doctors start prescribing it for, say, sleeplessness? I have to say, I don't think so. There's plenty of drugs out there for sleeplessness. And if you were a doctor, would you really prescribe this drug, knowing the potential harm that it could cause, for something as trivial as sleeplessness? Probably not, for the simple reason that you don't want to get sued.

BOGAEV: What do the doctors that you've talked to think about the resurgence of thalidomide? They're the ones who are really faced with difficult ethical decisions when it -- when it comes to prescribing it for women -- for their women patients.

STOLBERG: Well, I would say doctors are reacting cautiously. A doctor's first obligation is to try to help his or her patients. And so for patients who really need this drug, I think doctors will be willing to prescribe it. But I think doctors are nervous about it.

I interviewed one doctor whose been prescribing thalidomide for a patient of his who has a very rare disorder called Bischette's (ph) Syndrome. And thalidomide really is the only drug that works for this woman. And she's been getting it under the same special program that has afforded leprosy patients an opportunity to receive this drug.

Now, he told me that another patient that this woman knows came to him and said, you know: "would you help me?" And he agreed to help her too -- get the drug. But he said, you know: "no more. I'm not doing this anymore because I don't want to take the risk." Doctors are afraid of getting sued and that's a big motivator in the practice of medicine right now. You don't want to get sued.

And a drug like this that can cause such disastrous problems, I think is going to be looked upon very cautiously by the medical community. The drug company estimates that in the first year, about 10,000 people will probably take thalidomide -- roughly one-tenth or about 1,000 of them women of childbearing age; most of them AIDS patients.

BOGAEV: Isn't there a gender bias issue here though? I mean, the subtext is, it's pretty demeaning to women. The assumption is they can't control their sex life.

STOLBERG: Oh, yeah. I mean, women's health activists are, you know, livid about this; about this idea that women should be excluded from getting a drug that they need and could benefit from, for exactly that reason. It's exactly as you stated. The assumption is that women can't control their sex lives, and that's an assumption that women's health activists are really urging doctors not to make. But unfortunately, this is the real world and I think some doctors are going to make that assumption.

BOGAEV: It must just be inconceivable to Randy Warren and other thalidomide victims that there might be another generation.

STOLBERG: You know, it is. It's terrifying to them. And it's very -- it's very sad and painful for them. You know, these -- these thalidomide babies were all born within a few years of one another. And in a way, they're like families. They're all each other have. They're growing older now. They're all in their mid-30s. Some of their parents are growing older and dying. And they always thought -- Randy Warren once said this to me, he said: "we always thought we would be the only generation."

And now suddenly they're bracing themselves for the next generation, and thinking: "if another baby is born, who will be there to help?" And their answer is: "we will."

BOGAEV: Sheryl Gay Stolberg, I want to thank you very much for talking with me on FRESH AIR.

STOLBERG: Thank you.

BOGAEV: Sheryl Gay Stolberg is a science reporter for the New York Times.

This is FRESH AIR.

Dateline: Barbara Bogaev, Philadelphia

Guest: Sheryl Gay Stolberg

High: New York Times science correspondent Sheryl Gay Stolberg talks about the comeback of the drug Thalidomide. In the 1960s the drug was banned worldwide after it produced a generation of babies with missing and stunted limbs. But it is now showing promise in treating leprosy and several other ailments, including AIDS.

Spec: Drugs; Health and Medicine; AIDS; Pregnancy; Thalidomide

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Thalidomide Comeback

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 09, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 020903NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Birthday Letters

Sect: News; International

Time: 12:55

BARBARA BOGAEV, HOST: The publication of a new volume of poetry isn't usually considered news. But a few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a front page story about British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes' new volume "Birthday Letters."

Book critic Maureen Corrigan tells us why these poems deserve to make headlines.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN, FRESH AIR COMMENTATOR: In life, you've gotta choose sides. You can't root for both Clinton and Starr, Duke and North Carolina, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. The bitterly opposing Plath/Hughes camps rallied immediately after Plath's suicide in February of 1963. Plath partisans see her as the fiery, but fragile genius, who was driven to take her own life when the awful Hughes deserted her for another woman.

Hughes' defenders, a much smaller band, regard him as a casualty of Plath's emotional instability -- a stoic gentleman who's been buried alive next to his vengeful wife for the past 35 years.

Time has not been on Hughes' side. As he stiffened into Britain's craggy poet laureate, Plath remains young and smiling -- ever the blond American innocent -- a gifted Gidget destined to fall victim to corrupt European sensibilities.

Hughes' resolute silence about Plath hasn't helped his cause either. Except for a few letters to the press and introductions to his wife's posthumously published work, he's remained mum on the subject of Sylvia. In a 1989 letter to one of Plath's biographers, Hughes explained his decision to keep silent:

"I preferred it on the whole," he writes, "to allowing myself to be dragged out into the bull ring and teased and pricked and goaded into vomiting up every detail of my life with Sylvia for the higher entertainment of 100,000 English lit profs."

But now, to the astonishment of the literati on both sides of the Atlantic, Hughes has just published a volume of 88 poems entitled Birthday Letters, which chronicles the course of his intimate relationship with Plath from their meeting in Cambridge, England in 1956 to his mandatory attendance at her decades-long wake.

Almost all are narrative poems directly addressed to Plath -- some responding to her greatest poems, like "Daddy." Hughes has been secretly writing these poems for years, and even if they were nothing more than jingles, they'd be big news. But they're marvelous -- baffled and angry, vivid and raw. Some poets create their subjects; others have their subjects thrust upon them. In Birthday Letters, Hughes finally has bowed to his fate.

The introductory poem, "Fulbright Scholars," depicts the young Hughes staring at a newspaper photo of Plath, whom he hasn't yet met. As he stares, he munches on a peach -- the first fresh peach this Brit, raised on war rations, has ever tasted. Hughes writes: "at 25, I was dumbfounded afresh by my ignorance of the simplest things."

That's pretty much Hughes' persona throughout this volume. Confounded by Plath's sophisticated demons, he's just a regular Yorkshire lad struggling to make things right. A few years into their marriage, the unwitting Hughes makes Plath a writing table out of an elm plank. "I revealed a perfect landing pad for your inspiration," he writes in the poem "The Table." "I did not know I had made and fitted a door opening downwards into your daddy's grave."

Those lines hinted at Hughes' over-arching argument in Birthday Letters; that is, that before he left Plath for another woman, she left him for her dead father, Otto -- the man Hughes believes she felt compelled to join through suicide.

Well, after enduring decades of blame for Plath's death, maybe Hughes is entitled to mount a self-serving defense. What's of even greater interest here, though, are his declarations of abiding love for Plath and his fierce sense of protectiveness towards her.

In "The Literary Life," perhaps the most extraordinary poem in this volume, Hughes remembers Plath's despair when the American poet Marianne Moore dismissed some of her early work. After Plath's death, Hughes once again meets Moore, who now daintily praises Plath's posthumous poetry. "And I listened," Hughes writes, "heavy as a graveyard, while she searched for the grave where she could lay down her little wreath."

All those years of living in the shadow of "Lady Lazarus" clearly have taught the once-taciturn Hughes a thing or two about the pleasures of giving way to fury.

BOGAEV: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University.

Dateline: Maureen Corrigan; Barbara Bogaev, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Book Critic Maureen Corrigan reviews "Birthday Letters" by English poet Ted Hughes. This is the much anticipated collection by Hughes who was once married to American poet Sylvia Plath. Many blame Hughes for Plath's suicide in 1963 after he left her for another woman.

Spec: Books; Authors; History; Divorce; Poetry; Ariel; Birthday Letters; The Bell Jar; Suicide

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Birthday Letters

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.