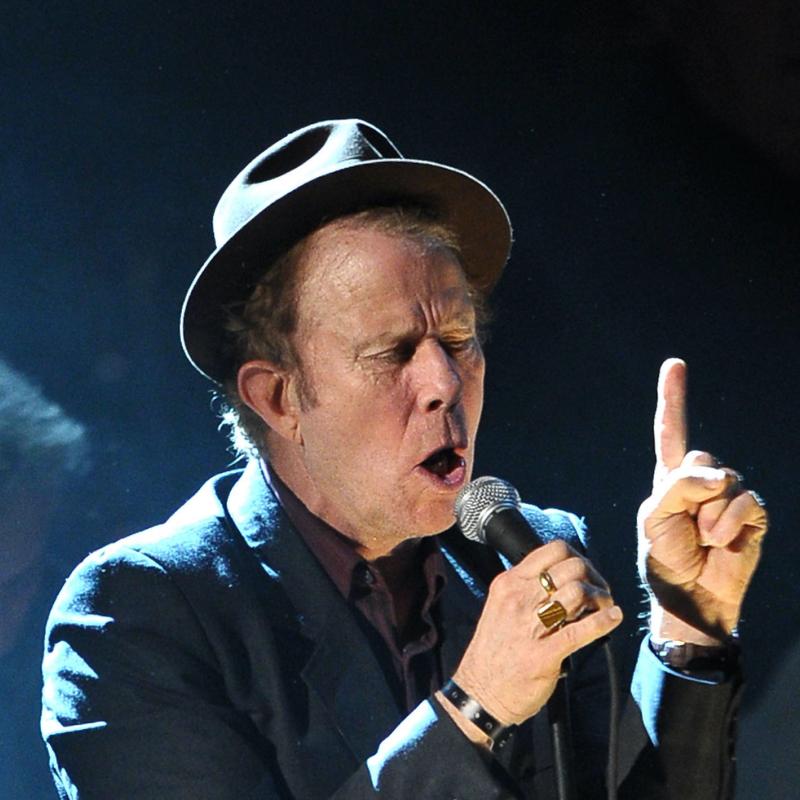

Tom Waits: A Raspy Voice Heads To The Hall Of Fame

On March 14, Tom Waits will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Fresh Air honors the gritty vocalist with highlights from a 2002 interview, in which he discussed his musical influences and his longtime collaboration with his wife, Kathleen Brennan.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on March 4, 2011

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110304

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Alice Cooper: The Gentle Man Behind The Shock Rocker

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli of tvworthwatching.com, sitting in for

Terry Gross.

On March 14th, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame will hold its 26th annual

induction ceremony. Among those to be honored are Neil Diamond, Leon Russell,

Darlene Love, Dr. John and two of our guests on today's show: Alice Cooper and

Tom Waits. We'll hear from Tom Waits in the second half of the show, but let's

start with one of the pioneers of what came to be known as shock rock.

The name Alice Cooper thrilled teenagers and scared parents in the 1970s. In

concert, his brand of theatricality was about breaking taboos and being

decadent. He wore makeup, black lingerie and a boa constrictor. He took a

hatchet to female mannequins and spit into the audience. He often ended his

performances in a guillotine.

As intentionally crude as his stage show was, some of his songs were really

catchy. A few of them became big hits, such as "I'm 18," "School's Out" and "No

More Mr. Nice Guy." Lots of bands have since copied Alice Cooper's looks and

theatrics.

Terry Gross spoke to Alice Cooper in 2007 and asked him how he transformed

himself from Vincent Furnier into Alice Cooper. But first, let's hear what may

be his most famous hit, from 1972, "School's Out."

(Soundbite of song, "School's Out")

Mr. ALICE COOPER (Musician): (Singing) Well, we got no choice, all the girls

and boys making all that noise 'cause they found new toys. Well, we can't

salute ya, can't find a flag. If that don't suit ya, that's a drag.

School's out for summer. School's out forever. School's been blown to pieces.

No more pencils, no more books, no more teachers' dirty looks.

TERRY GROSS, host:

Alice Cooper, welcome to FRESH AIR. Alice Cooper, I mean, the act, the Alice

Cooper act is - it's theater. I mean, it's not just a concert. It's theater.

It's a whole persona, and, you know, there's, like, special effects. There's a

snake.

I mean, there's - you know, over the years, you've done, you know, things with

- crude things with mannequins. Alice gets executed at the end. Why did you

want to do rock as theater as opposed to just, like, doing straight concerts

like most people were doing at that time?

Mr. COOPER: That's exactly it, right, just what you said, the idea of just

doing a straight concert with no fun in it - you know, I mean, rock and roll,

the most theatrical music in the world, and nobody was doing anything.

I would look at bands that I really admired like The Who and The Yardbirds, The

Rolling Stones, and their theatrics were built into the character. You know,

they had - like, Pete Townshend was very theatrical. Mick Jagger was very

theatrical. But I looked at the whole stage - and you have to remember, the

original band were all art students. And we looked at that, and I said: Why

aren't they painting that canvas? You've got this entire stage up there, and

nobody's doing anything with it.

I also looked around and I said: Rock and roll is full of Peter Pans. Where's

Captain Hook? And I will gladly be Captain Hook. I always thought the villain

always got the best lines. The villain was always the one that everybody kind

of really wanted to see.

And so I created this Alice Cooper character to be all of those villains

wrapped up into one, you know, with this certain amount of tongue-in-cheek. I

definitely - you can't do horror without having a punch line. I think you need

to make the audience laugh. If you scare them, you need to make them laugh at

the same time.

GROSS: There's been so many stories over the years about how you created the

Alice Cooper persona. I'd love to hear you tell the story.

Mr. COOPER: We were a good rock band. We lived with the Pink Floyd and, you

know, we were, you know, playing gigs with The Doors and The Mothers of

Invention and all that. Nobody would record us.

Finally, Frank Zappa did record us and, you know, put us on Warner Brothers.

But there was that moment of saying: I'm - we're frustrated. We better do

something that's going to get a lot of attention.

That's when Alice was created. That's when I said: Let's create this character

that every parent in the world is going to hate. You know, Alice Cooper. It's a

guy. It's a band of guys. We're wearing makeup. We're wearing our girlfriends'

lingerie, only we've got black leather pants on and codpieces, and we have

canes.

We're more of "Clockwork Orange" than "Clockwork Orange." We were as - and we

didn't mind a little bit of violence up there. We borrowed a little bit of

"West Side Story." This was 1970, when people were easily shocked. I always

said that we were the band that drove the stake through the heart of the love

generation, you know? We were the next thing.

But the thing about it was, I looked at "Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?" you

know, Bette Davis. And I looked at that old lady with that caked makeup on and

sort of those black, smeared-on eyeliner, and I said: That's truly frightening.

That, to me, is scary.

And then we saw "Barbarella," and we saw - Anita Pallenberg played the black

queen. And I said: That's what Alice should look like, right there. And, you

know, all the guys were all straight. You know, nobody was gay. But we had no

problem, you know, wearing a piece of women's clothing.

GROSS: Dressing in things like, what, like leather corsets and wearing makeup

and...

Mr. COOPER: Well, yeah, sure. I wouldn't have any problem with that, as long

as, you know - I mean, I was very secure with my manhood. Girls loved it.

GROSS: They did?

Mr. COOPER: The girls - oh, yeah, are you kidding? Because everybody was - you

know, Neil Young and Stephen Stills, and everybody was this, you know, hippie,

hippie kind of look. And all of a sudden, here was this band of guys that were

kind of like androgynous. And this was pre-Bowie, and you're wearing a great

big boa, you know.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COOPER: And you're wearing black leather - tight black leather jeans and

boots and a switchblade and your girlfriend's slip-top that's all cut up, with

blood all over it, and black leather gloves. And this is 1968, '69. People are

going: Oh, no. My son's not going to - that's not going to be my - so that -

when they walked into their room, and that poster was in their son's room, why

do you think that poster was in there? Because mom and dad hated it so much.

BIANCULLI: If you're just joining us, we're listening to an interview Terry

Gross recorded with Alice Cooper in 2007. He'll be inducted into the Rock and

Roll Hall of Fame later this month.

Terry asked him how the band came up with its name.

Mr. COOPER: We were sitting around, and we were talking about what could we

name ourselves. Now, the obvious thing is, you know, some horrific name, you

know, Venom or something like that, you know, Husky Baby Sandwich or something,

you know.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: And we're sitting there, and I went: Alice Cooper. And it was the

first name that came out. I said: What if it was like a little old lady's name,

a little old librarian, you know? But this little old librarian is, like, a

serial killer, you know. Nobody ever suspects her. It sounds like a little

girl, Alice Cooper, a little sweet little girl, and they get us.

And we all kind of liked that idea, the fact that nobody would see us coming.

And what we were - I mean, we were actually pre-"Clockwork Orange," and

"Clockwork Orange" borrowed an awful lot of Alice Cooper: the codpieces, the

canes, the snakes, the makeup. The guy's name was Alex, not Alice. There was a

ton of Alice Cooper in "Clockwork Orange."

GROSS: You mentioned in your memoir that, as a kid, you know, you were an

athlete. You wrote for the high school paper. You were pretty popular. You were

cool. But you couldn't fight.

So when you're on stage and you were being, like, the scary villain character,

the horror character, was there any kind of compensatory aspect to it because

you couldn't fight as a kid, but here you were being this, like, scary guy?

Mr. COOPER: Well, you know, the funny thing was, was it wasn't that I couldn't

fight. It was the fact that - in fact, I was from Detroit, where you better -

you know, I got into a lot of fights when I was a kid in Detroit.

And then when we moved back to Detroit, again, back to the toughest

neighborhoods in the world, it wasn't that I couldn't fight. It was just that I

was the great diplomat. I was the dark side of Ferris Bueller.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: I could talk my way out of a sunburn, you know, and I was always

good at talking my way out of it. You know, I always said: Why would you want

to beat up me? I weigh 100 pounds. You know, the guy was going to beat me up,

and I'd go: I'll tell you what. Name me a girl in this school, and I'll get you

a date with her.

GROSS: Could you do that? Could you deliver?

Mr. COOPER: Oh, absolutely. The girls loved us, you know.

GROSS: How would you do it? How would you get the date?

Mr. COOPER: I was just a charmer. I was an absolute charmer. I'd go to the

girl, and I'd go: Hey, look, you know, you're the best-looking girl in school.

I mean, everybody knows that. And this guy over here is going to kill me if you

don't do this. You know, could you just do me a favor and go out with this guy,

and honestly, I'll owe you a big favor after this.

You have to remember now, in high school, we were the biggest band in Phoenix.

We played at the best club in Phoenix, and we had a record on the charts when

we were in high school. We owned that school. We owned everything about it.

And on top of it, we were athletes. We were four-year lettermen. We had the

jocks covered. We had the - you know, we had the - everybody out there, and

honestly, nobody could beat me up because I was in the letterman's club. They'd

get killed by the football team. You couldn't beat up a letterman, you know.

So, I mean, honestly, we had that school so wired, it was unbelievable.

GROSS: I find it so kind of amusing that you're so, like, easy to talk to, and

you are such a charmer, and how different that is from the Alice Cooper stage

image.

Mr. COOPER: Well, the Alice character has never, ever talked to the audience. I

mean, I looked - when I created this character, I said: Well, what would he do?

What wouldn't he do?

You know, you have to remember now, Alice is my favorite rock star. I create

Alice to be - what would I want to see this character do? And I talk about

Alice in the third person because when I play Alice, I play him in the third

person.

And so would Alice say thank you? No. Alice wouldn't get up there and go: Gee,

I hope you like us tonight. Here's a song we wrote in 1968, and all this.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: Alice gets up there and grabs them by the throat and says: Come

here. You're mine. It's almost - he's almost the dominatrix, you know, and the

audience is his trick, as far as he's concerned.

BIANCULLI: Alice Cooper, speaking to Terry Gross in 2007.

More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: Let's get back to Terry's 2007 interview with Alice Cooper, one of

the artists being inducted later this month into the Rock and Roll Hall of

Fame. He had many dramatic and bloody ways to end his stage shows, and Terry

asked him to describe his favorite, which turns out to be him in a guillotine.

Mr. COOPER: There's a certain amount of real anticipation behind it. You see

that blade, it's a 40-pound blade. It's razor-sharp, and it really only misses

me by about six inches.

GROSS: It's a real guillotine?

Mr. COOPER: Oh, yeah, and it's a good trick. But if I didn't do the trick

right, it would cut my head off. I mean, it's - you have - don't try this at

home, by the way. I'm a professional.

GROSS: Can you describe the trick, or...

Mr. COOPER: In case any of you people have guillotines at home. Well, it's a

trick. It's an old vaudeville trick. In fact, you know, when guys like Groucho

Marx would come to the show - Groucho saw us as the last - he always called me,

he says: You're the last hope for vaudeville.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: And he would bring Jack Benny and George Burns and Mae West. And

people like that would come to the show because it was vaudeville to them. They

said: Ah, remember 1923? The Great Floyd used to do that. You know, the

(unintelligible). Of course, he would have doves come out of his sleeves when

he - and this was nothing new to these guys.

They would - you know, Groucho would come to the show, and he'd see it, and

he'd go (mumbles). You know, he'd insult everybody there. Excuse me, I've got

to go insult the maitre d', you know, that kind of thing. We were best of

friends, Groucho and I were. But they saw it as vaudeville, and actually,

that's what it is. It's rock and roll vaudeville.

But this generation, the last five generations have no idea what vaudeville is.

So to them, it's something new. It's some kind of strange, dark cabaret.

GROSS: So can you describe the guillotine trick, like, how it's done?

Mr. COOPER: Well, the guillotine, you actually - you are in the guillotine, in

a stock, right, and you are holding yourself up with the hands. The audience

sees your head in the stock, and there's a basket in front of you.

What they don't see is that when the guillotine comes down, at one point, you

let yourself go, and your whole body drops, OK. They don't see that. They only

see your head lop off. They see your - because they only see your head fall

down. And then there's a fake back that comes up and gives it the illusion that

your head literally comes off.

Now, we learned the trick. The Great Randy was one of the guys that helped us

with it. And it looks perfect. And then, of course, the guy, the executioner

pulls the head out, and the head is rigged so that he looks at the head, he

talks to it, and he turns around, and the head spews blood out of its mouth

into the audience, like it throws up what's left of - he's not dead yet, you

know.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: Now, it's so over the top, that if you're not laughing by now,

there's something wrong with you. Because it's...

GROSS: But the thing is, though, that some of your fans took it really

seriously, which leads to the chicken story. It leads to the chicken story.

Mr. COOPER: Yeah, yeah, which, of course...

GROSS: Tell the chicken story.

Mr. COOPER: Well, no, the chicken story was one of those things that nobody saw

that one coming. We're playing in Toronto, and my manager, Shep Gordon, who

I've been with 38 years, who was also total vaudeville, totally gets it, you

know. He's the one guy that always goes: Let's go for the Hollywood publicity

stunt, you know.

He - we just - we were going to go on between John Lennon and The Doors. Now,

you have to remember, nobody's ever heard of us. But he promoted the concert,

and 60,000 people there, and we didn't get paid. Our payment was that we went

on at the end, between the two biggest acts.

So in the end of our show, we always used to do a thing where we would open up

a feather pillow and CO2 cartridges, and the whole stage was a flurry of

feathers. In the middle of all this, all of a sudden, I look down, and there's

a chicken. Somebody threw a chicken onstage.

Now, it never occurred to me - here's a guy, let's see, I've got my keys. I've

got my tickets. I got my drugs. I got my chicken. I got...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: Who would bring a chicken to a rock concert? It wasn't us. We

didn't bring it. I mean, I didn't - I'd never thought of using a chicken on

stage.

So there's this white chicken, and being from Detroit, never being on a farm in

my life, it had feathers, it had wings, it was a bird, it should be able to

fly. Is that not logical? I - oh, yeah.

GROSS: Oh, I understand.

Mr. COOPER: And I pick it up, and I kind of like softly, you know, throw it

into the audience, where it didn't fly as much as it plummeted into the

audience, and the audience tore it to pieces.

The next day in the paper: Alice Cooper rips chicken apart and drinks the

blood. I was the new geek of all time. Of course, nobody had a picture of it,

because it didn't happen. Now, I got a call the next day from Frank Zappa, who

was producing me at the time, and he goes: Alice, did you kill a chicken

onstage last night? And I went: No. He said: Well, don't tell anybody. They

love it. He says, everybody's talking about it.

GROSS: I guess there's a part of me that wonders if, in a way, Alice wasn't the

villain here in the sense that maybe the fans were kind of behaving the way

they thought you wanted them to behave, or the way they were expected to behave

at an Alice Cooper concert. You know, a chicken, yeah. We're villains, too.

Let's get the chicken.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: That could - you know, be it. And it also could be the fact that

they were the ones that were high. We weren't.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: We were in the band. We didn't get high. We drank a little beer.

That was about it.

GROSS: Can I just name a few names to you and get your really short take on

them?

Mr. COOPER: Sure.

GROSS: Great. KISS.

Mr. COOPER: KISS, we told KISS where to buy their makeup. Everybody wanted

there to be a huge feud between KISS and us, because they were the great

copycats. Alice came out with the makeup. KISS came out with the makeup. Their

very first statement was: If one Alice works, then four ought to work.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COOPER: Now, my joke with them - and they're friends of mine - was they use

pyro. I never used pyro. I said: As long as you guys do - don't do my show and

do different records, there's room for us both out here. Just don't be Alice

Cooper.

So they turned into four comic-book characters. They were like the X-Men,

whereas Alice Cooper was Phantom of the Opera, you know. I always used to

laugh, and I'd say: When you guys can't think of anything clever to do, you

just blow something up.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: OK. Marilyn Manson.

Mr. COOPER: Marilyn Manson, you know, understood what Alice was, looked at it

and said: I'm just going to up the ante. I'm going to be Marilyn Manson. OK:

Alice Cooper, Marilyn Manson. OK. Let me see, a girl's name. Gee, I wish I

would've thought of that. Makeup - oh, wait a minute, I did that.

But he said: OK, my thing is: Now, Alice did makeup, snakes and violence, mock

violence on stage. OK, what am I going to do? OK, I'm going to be a devil

worshipper, drug addict, duh, duh, duh. That'll get him.

What he does is very stylistic. I don't - I think he's missing the sense of

humor in it, and I certainly object to a lot of the things when it comes to

tearing pages out of the Bible. And he became an anti-Alice as soon as he heard

I was Christian.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. COOPER: He's publicly said: Alice is - I hate Alice now. Why? Because he's

Christian.

GROSS: And I want to ask you about Frank Sinatra, and here's why: In a concert

film from 1973, you come out first in a white tuxedo, singing "The Lady is a

Tramp," a song Sinatra made famous.

Mr. COOPER: (Singing) She gets too hungry for dinner at eight. Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. COOPER: Well, he was the first punk.

GROSS: Wait, wait, wait. Then you say, in the middle of the song, you go: I've

had enough of this. And you act, like, really angry, and you strip out of the

tuxedo and start getting into Alice Cooper drag. But I figured you must love

Sinatra.

Mr. COOPER: Love Sinatra. It was - he actually was a friend. And Frank Sinatra

totally got Alice Cooper. In fact, all of the Hollywood guys, the old pros, got

Alice Cooper. They got it. They understood what it was. They saw the image.

They said: Oh, I get it. OK, cool. He's playing this thing to the hilt. Way to

go. And the hit records keep coming.

Frank Sinatra did one of my songs. He did "You and Me" at the Hollywood Bowl

one night. I actually got along quite well with Frank Sinatra. He looked at me

as an original, and, of course, everybody - you can't beat Sinatra. He's the

best voice of all time.

GROSS: Well, Alice Cooper, it's really been fun talking with you.

Mr. COOPER: Well, thank you very much. We hit on some fun stuff.

BIANCULLI: Alice Cooper, speaking to Terry Gross in 2007. On March 14th, he'll

be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. We'll hear from another

inductee, Tom Waits, in the second half of the show.

I'm David Bianculli, and this is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

134230317

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110304

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Tom Waits: A Raspy Voice Heads To The Hall Of Fame

(Soundbite of music)

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli sitting in for Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of song, "Misery Is The River Of The World")

Another of the inductees in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year, along

with Alice Cooper, is singer-songwriter Tom Waits. Critic Daniel Durchholz

described his voice as sounding, and I quote, "like it was soaked in a vat of

bourbon, left hanging in the smokehouse for a few months, and then taken

outside and run over with a car."

Here is that voice singing "Misery Is The River Of The World."

(Soundbite of song, "Misery Is The River Of The World")

Mr. TOM WAITS (Musician): (Singing) The higher that the monkey can climb, the

more he shows his tail. Call no man happy 'til he dies. There's no milk at the

bottom of the pail.

God builds a church. The devil builds a chapel like the thistles that are

growing 'round the trunk of a tree. All the good in the world you can put

inside a thimble and still have room for you and me.

If there's one thing you can say about mankind, there's nothing kind about man.

You can drive out nature with a pitch fork. But it always comes roaring back

again.

Misery's the river of the world. Misery's the river of the world. Misery's the

river of the world.

BIANCULLI: Tom Waits is one of the true eccentrics of pop music. The people he

sings about are usually outlaws, drunks, hobos, and losers. The darkness of his

lyrics is accentuated by the rumble and rasp of his voice; a voice that sounded

old even when he was young.

Waits has been recording since 1973. His songs have been used on the

soundtracks of several films and he's acted in the movies "Down By Law," "Short

Cuts," "Wolfen," "Bram Stoker's Dracula" and "Coffee and Cigarettes."

Terry spoke with Tom Waits in 2002.

TERRY GROSS: Some of your music writing seems influenced by the German songs of

Kurt Weill. Have you listened a lot to him? Do you feel like he's influenced

your writing?

Mr. WAITS: Well, you know, I hadn't really listen to him until I had people

tell me that I sounded somewhat like him or had some influence in there, so I

said, well I better start listening to this stuff and...

GROSS: What did you think?

Mr. WAITS: Yeah, I liked it. It was really â a lot of it's really angry. And I

guess I like beautiful melodies telling me terrible things.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Well put. Yeah.

Mr. WAITS: And, so it works for me, you know.

GROSS: What was the music that you grew up listening to because your parents

were listening to it? I mean before you were old enough to choose music

yourself. What was the music in your house?

Mr. WAITS: Really, Mariachi music, I guess. My dad only played a Mexican radio

station and then, you know, Frank Sinatra and later Harry Belafonte. And then,

you know, I would go over to my friends' houses and I would go into the den

with their dads and find out what they were listening to. That's what I was

really - I couldn't wait to be an old man.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: I was about 13, you know, I didn't really identify with the music of

my own generation but I was very curious about the music of others. And I think

I responded to the song forms themselves. You know, cakewalks and waltzes and

barcaroles and parlor songs and all that stuff, I think I â which is just

really nothing more than Jell-O molds for music, you know. But I seemed to like

the old stuff: Cole Porter and, you know, Oscars(ph) and Hammerstein and

Gershwin - all that stuff. I like melody.

GROSS: So when you were 13 being more interested in the music of your friends'

parents then in your friends' music, what was the music of your generation that

didn't interest you?

Mr. WAITS: You know, like the Strawberry Alarm Clock, or I didn't really or...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. WAITS: But later I liked that stuff, you know like The Animals and Blue

Cheer and, you know, Led Zeppelin and all that stuff, and The Yardbirds and,

you know, of course, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles and Bob Dylan and James

Brown, I was really hot on James Brown.

GROSS: Now you said your father listened mostly to the Mexican station and to

Mariachi music.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah.

GROSS: Was your father Mexican?

Mr. WAITS: No my dad's from Texas. He grew up in a place called Sulphur

Springs, Texas. And my mom's from Oregon. She listened to church music, you

know, all that Brother Springer and all the...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: She used to send money into all the preachers, you know. And, but

the early songs I remember was "Abilene." When I heard "Abilene" on the radio

it really moved me. And then I heard, you know, Abilene, Abilene, prettiest

town I've ever seen. Women there don't treat you mean. And "Abilene," I just

thought that was the greatest lyric, you know, women there don't treat you

mean. And then, you know, "Detroit City," last night I went to sleep in Detroit

City...

(Singing) And I dreamed about the cotton fields back home.

I liked songs with the names of towns in them.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: And I think I like songs with weather in them.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: And something to eat.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: So I feel like there's a certain anatomical aspect to a song that I

respond to. I think, oh yeah, I can go into that world. There's something to

eat, there's the name of a street.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: There's a - OK, and there's a saloon, OK. So I think probably that's

why I put things like that in my songs.

GROSS: I want to play another track from "Blood Money" and this is called "A

Good Man Is Hard To Find." This is Tom Waits.

Mr. WAITS: Sure.

(Soundbite of song, "A Good Man Is Hard To Find")

Mr. WAITS: (Singing) Well, I always play Russian roulette in my head, 17 black

or 29 red. How far from the gutter? How far from the pew? I will always

remember to forget about you.

A good man is hard to find. Only strangers sleep in my bed. And my favorite

words are good-bye. And my favorite color is red.

GROSS: Now, I want to ask you about your voice. You have a very raspy singing

voice. Was that a sound that you strove for, you know, that you worked on

having? Or is it what naturally developed?

Mr. WAITS: It's an old man thing. I couldn't wait to be an old man.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: Old man with a deep voice.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: No, I scream into a pillow.

GROSS: Well, you know, John Mahoney, the actor?

Mr. WAITS: Sure. Yeah.

GROSS: He told me he actually did stuff like that.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah?

GROSS: That he wanted a distinctive voice.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: And so he used to do these exercises that he practiced in a closet of

just like shouting and trying to, you know, like growl a lot and...

Mr. WAITS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...it actually permanently did something to his vocal chords as a result

of it.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah, hooray. I'm all for it.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Was, say, Louis Armstrong an influence on you?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah, yeah. Sure. You know, you can't ignore the influence of

someone like Louis Armstrong. It's a, you know, he's like a river. He's like a

country to be explored in of itself and but, yeah, he was like, he came out of

the ground just like a potato, you know, he's completely natural. And, yeah,

sure, I love those tunes. And, but this one, this "A Good Man Is Hard To Find,"

was, you know, was an attempt to kind of tip my hat somewhat to that.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah.

GROSS: Have you ever worried about hurting your voice by...

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I've hurt it. Yeah, I have hurt it. But I have a voice doctor in

New York who used to treat Frank Sinatra and various people. He said, oh you're

doing fine, don't worry about it.

GROSS: Oh, that's good.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Now you once said that you wish you could have been a part of the Brill

Building era in which people like Carole King and Leiber and Stoller and Ellie

Greenwich and Jeff Barry were writing songs for singers and for vocal groups.

What do you think you would have liked about that?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I guess writing at gunpoint sounds really exciting to me, those

kinds of deadlines.

I went into a rehearsal building on Times Square in New York one afternoon and

I - in a really tiny little room. In fact, it was probably smaller than the

room I'm in right now, which is a little larger than a phone booth. There was

just enough room for a little spinet piano and then you could just barely close

the door. And there you were. And it was, and you could hear every kind of

music coming to you, through the walls and through the windows and underneath

the door.

And you heard African bands and you heard like, you know, comedians and you'd

hear applause every now and then and you'd hear tap dancers. And I think I just

like the whole melange of it, you know, how it all kind of mixes together.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: I like turning on two radios at the same time and listening to them.

I like hearing things incorrectly. I think that's how I get a lot of ideas is

by mishearing something.

GROSS: Well, what was your first instrument?

Mr. WAITS: I don't know. I don't know, probably a box or something.

GROSS: But, I mean the first instrument instrument.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, my dad gave me a guitar when I was about nine and, you know, I

learned "El Paso." And actually, I learned it in Spanish because he wouldn't

purchase any, you know, like English-speaking records.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: He didn't like them. And, in fact, I remember going by...

GROSS: This is your father?

Mr. WAITS: This is my dad, yeah. We went by a stop sign once. There was a guy

in a hotrod was, you know, with the ducktail and everything, greased down hair

combed way back. And he's gunning the motor and we're in the station wagon and

he looked over at the guy like you know, and then he looked over at me as if to

say don't get any ideas, you know?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: And, but I yeah, so I had a guitar. I learned three chords. I

thought I knew everything and then it kind of grew from there.

GROSS: Now you dropped out of high school. Why did you drop out? Is there

something that you wanted to do instead or did you just hate going?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I wanted to go into the world.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: Enough of this.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: I didn't like the ceiling in the rooms. I didn't like the holes in

the ceiling, the little tiny holes and the corkboard and the little - the long

stick used for opening the windows.

GROSS: Oh God, yeah we had one of those in my elementary school. Yeah.

Mr. WAITS: Ah, I just hated all that stuff.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: I was real sensitive to my visual surroundings and I just, you know,

I just wanted to get out of there.

GROSS: Did you ever do the street musician thing?

Mr. WAITS: I didn't, but when I see people do it I say, aw, man, I should have

done that. That's how you really get your chops together, you know. But my

first gigs, my first big gigs were opening a show for Frank Zappa and I think

that was difficult. I was kind of like the rectal thermometer for the audience.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WAITS: And it was a little awkward for me. I was alone and I was performing

in front of large groups of people and they were verbally abusive. And I think

it - I'm like a dog, I was beat as a dog, so.

GROSS: Is there a point in your career that you see as a turning point from

getting to where you are now from where you were when you started performing?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah. Probably, well, I got married, really, you know, that was

it. You know, I mean that's like the most important thing I ever did. And then,

Kathleen, really was the one who encouraged me to produce my own records, you

know?

GROSS: Mm-hmm. What kind of music background is she from?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, gee, I don't know. She's got like opera in there and she was

going to be a nun, you know, so we changed all that.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Yeah, I guess so.

Tom Waits, thank you so much. It's really been great to talk with you. Thank

you.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, we're all done?

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, OK. Nice talking to you, Terry.

BIANCULLI: Tom Waits, speaking to Terry Gross in 2002. The 26th Annual Rock and

Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony will be held March 14th.

Next week, we'll feature interviews with other artists to be honored at that

same ceremony: Darlene Love, Neil Diamond and Dr. John.

Coming up, a look at the new onslaught of reality shows on broadcast

television.

This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

134236977

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110304

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

'Next Great Restaurant': Delicious Reality TV

(Soundbite of music)

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm TV critic David Bianculli.

On broadcast television, the February ratings sweeps ended Wednesday. Sweeps

periods are when the networks compete aggressively to attract the largest

audiences because those are the numbers used to set advertising rates for the

next three months.

That's why now that the February sweeps are over, almost all network shows are

reruns - and it's also why we're about to face a new onslaught of reality TV

shows.

Reality shows are a low-cost, low-risk way of rolling the dice and hoping for a

sudden hit. If it doesn't catch on, no big deal. You finish out the cycle and

replace it with something else, or scrap it immediately if the ratings are that

low. But if it hits big, it's a major moneymaker.

Yet, a decade into the current cycle of broadcast TV reality shows, much of the

novelty has worn off.

Even the durable programs have to rely on tricks to keep audiences coming back.

Donald Trump's "The Apprentice" series, on NBC, has upped the ante with

celebrity editions for a while now - even though its definition of celebrity is

way too generous.

This Sunday, the newest cycle of "Celebrity Apprentice" premieres, and the

loosest cannon in its arsenal is Gary Busey, whose level of quirkiness has

fueled other reality shows in the past. So here he is, misbehaving again, with

predictable unpredictability.

And that's the problem with reality TV this year: Even when the programs aren't

familiar reruns, the contestants are. On CBS, we have former "Survivor"

contestants Russell and Boston Rob fighting it out on new teams. On the same

network's "The Amazing Race," we have 16 losing teams from former editions,

lining up to try, try again.

Another problem is that even a new show can seem old, because its parts are so

familiar. ABC this weekend launches "Secret Millionaire," which is an

unwatchable rip-off of the nearly as manipulative "Undercover Boss" on CBS. Is

there any broadcast TV reality show with a spark of originality these days?

Yes, there is - and, like "Secret Millionaire" and "Celebrity Apprentice" and

"The Amazing Race," it shows up this Sunday. It's NBC's "America's Next Great

Restaurant," and it comes from the producers of Bravo's "Top Chef."

There are two variations that make this new show stand out. One, is that

instead of having cooks compete for prizes, or a dream job in a top restaurant

- as they do on "Top Chef" and Gordon Ramsay's "Hell's Kitchen" - this time

they compete for investors and the chance to launch a dream business.

That's a familiar idea, too, from such shows as ABC's "Shark Tank," but in

"America's Next Great Restaurant," all the contestants are competing in the

same category for the backing to open a chain of three restaurants. They're

trying to impress the likes of chefs Bobby Flay and Curtis Stone, and this

time, the panel isn't just judging, it's mentoring. Here's the way the narrator

describes it in Sunday's premiere.

(Soundbite of NBC's "America's Next Great Restaurant")

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Man: Each week, the contestants will work side-by-side with the

investors to further develop their concepts. They'll hire chefs, design a

uniform, operate their own food truck and build their restaurant. And each

week, someone will go home.

Mr. BOBBY FLAY (Chef): I'm sorry. We will not be investing in your restaurant.

Unidentified Woman #1: I know that I'm a good chef.

Unidentified Woman #2: I'm going to miss her (unintelligible) so much.

Unidentified Man: The stakes couldn't be any higher.

BIANCULLI: The stakes, in that context, don't refer to juicy grilled pieces of

meat - but those come later, along with casual restaurants built around grilled

cheese sandwiches, Indian fusion and meatballs.

In episode one, the judges hear the pitches, taste the food and select the

finalists. In week two, the contestants are taken to an open-air mall to set up

booths and serve one sample item to a crowd of 1,000 people, each of whom has a

vote. And the judges are checking them out too - passing judgment on everything

from the food to the logo and even the name.

Here are Bobby Flay and Curtis Stone sampling the wares of one contestant who

is serving up small bowls of meatballs. He's nervous as the judges taste a

sample, happy as they ask for more, then nervous again as they turn around and

start questioning some of the customers, asking them specifically about the

name he's chosen for his would-be restaurant.

(Soundbite of NBC's "America's Next Great Restaurant")

(Soundbite of applause)

Unidentified Woman #3: Thank you very much. Thank you.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. CURTIS STONE (Chef): What have we got here?

Mr. FLAY: (Unintelligible).

Mr. JOSEPH GALLUZZI (Contestant, "America's Next Great Restaurant"): We've got

saucy balls, sir. How are you?

Mr. STONE: The amount of sauce compared with the meatball, they really are

saucy balls.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. GALLUZZI: Thank you. Thank you.

Mr. FLAY: Tell us about the name and the logo.

Mr. GALLUZZI: Putting grandma up there. To me, it shows that you're going to

have a nice home-cooked meal here.

Mr. STONE: Do you think that the name saucy balls, do you think there's anyone

that might find it a little bit bad taste?

Mr. GALLUZZI: I think we'll attract a lot more people than we'll offend with

that name.

Mr. FLAY: You want another one? You all right?

Mr. STONE: Yeah.

Mr. GALLUZZI: Woo. Yeah.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. FLAY: Well, the food is delicious. Does it offend anybody? Nobody's

offended by it?

Unidentified Woman #4: No, it's not that offensive, but...

Unidentified Woman #5: No. Like if you're with friend but it's, you wouldn't be

like hey, grandma, let's go eat a saucy ball, you know?

BIANCULLI: I suspect that with this show, as with "American Idol," a finalist

need not win to succeed. After a few weeks of exposure on a show like this,

they might find other investors eager to help them make their dreams come true.

But for that to happen, "America's Next Great Restaurant" has to last a few

weeks. And most new TV shows, like most new restaurants, fail quickly.

But "America's Next Great Restaurant" - with a tone that is more positive than

negative - is one show I expect will beat the odds. The judges are sincere and

likable, the show taps into a common dream, it makes me smile - and at times,

it even makes me hungry.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: Coming up, film critic David Edelstein reviews a new French film,

"Of Gods and Men."

This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

134205599

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110304

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

'Of Gods And Men': A Moving Test Of Faith

(Soundbite of music)

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

The story of the kidnapping and subsequent death in 1996 of seven French monks

in Algeria is the basis for the new French film "Of Gods and Men." The monks

were kidnapped by an armed Islamic terrorist group, but it remains unclear who

actually murdered them. The film won the grand prize at last year's Cannes Film

Festival.

Film critic David Edelstein has a review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN: "Of Gods and Men" is the English title of Xavier Beauvois's

stark drama, "Des hommes et des dieux," which is, of course, "Of Men and Gods."

It's a small reversal, but it bothers me. The film is foremost about men:

French Trappist monks in the mid-1990s doing good works in a poor Algerian hill

town. It centers on whether they should stay in their monastery while Islamic

terrorists are roaming the countryside killing foreigners and non-

fundamentalists.

In answer to the monks' prayers for guidance, there is no sign from on high,

and no moment in the film you might call transcendental - heavenly light or

soaring music or anything that suggests divine intervention. It's all rather

plain and down-to-earth. Faith, the film implies, is hard won, and the battle

to discern God's will never ends.

What is that will? The Islamic extremists' god is intolerant and cruel; the

monks' compassionate and nonjudgmental. The focus, throughout, is on the human

perception of the almighty. So: of men and gods.

Whatever the film's title, the monks' intransigence is controversial - even,

early on, within the fold. They're seen praying and chanting, toiling in the

fields, teaching and giving medical aid and affectionately interacting with the

locals - all while debating whether they should, indeed, get out.

The country's military officials strongly urge them to flee; and some of the

brothers feel their exit is inevitable. But the abbot, Brother Christian,

played by Lambert Wilson, quietly refuses to let go of his mission. He does not

even accept the military's offer of armed guards at night. He says he'll lock

the door.

It's a mark of the movie's power that you rarely feel like slapping Brother

Christian and dragging him to a departing plane. It's also a mark of its even,

lucid spirit that this view of Christian missionaries bringing Western

civilization to the Arab world doesn't play like old-fashioned colonialist

propaganda.

Director Beauvois shows over and over how the brothers accept the locals'

faith. Brother Christian studies the Quran, and even says goodbye to a village

friend with Insha'Allah, meaning, God be with you. He attends the Muslim

equivalent of a christening and doesn't flinch at prayers asking Allah for help

against the people of the unbelievers. The great old French actor Michael

Lonsdale plays the gentlest monk, the physician who also counsels a young

village woman on love. They are men who see themselves as representatives of

their loving god.

"Of Gods and Men" has a somewhat monotonous structure; basically, we're waiting

for the bad guys to show up. But the brothers' debates pull you in. One says he

didn't become a monk to have his throat slit. Another asks whether martyrdom

will truly serve a higher purpose. Brother Christian is adamant that quote,

"the good shepherd doesn't abandon his flock for the wolves."

After the final decision is made, Beauvois delivers a tour-de-force sequence in

which his camera holds on each man alone with his own thoughts - and even

though they're listening to the now over-familiar overture from "Swan Lake,"

it's so moving, you can nudge out of your mind the vision of Natalie Portman

swooning in a flutter of bloody feathers. Even ye of little faith will be

envious when the brother played by Michael Lonsdale's says, I'm not scared of

death. I'm a free man.

BIANCULLI: David Edelstein is film critic for New York magazine.

Lambert Wilson, one of the stars of the film "Of Gods and Men," is well-known

in France for his many roles in movies, TV shows and musicals. Here he is

singing on his collection of French songs recorded in 2007.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. LAMBERT WILSON (Actor): (Singing) (Foreign language spoken)

BIANCULLI: For Terry Gross, I'm David Bianculli.

(Soundbite of music)

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

134239573

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.