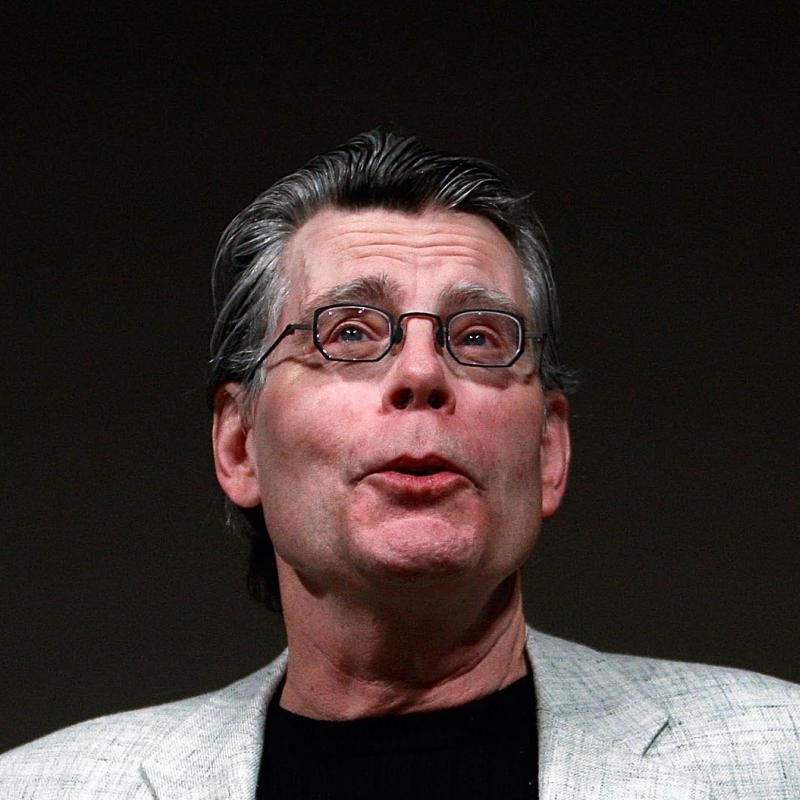

Stephen King On Growing Up, Believing In God And Getting Scared.

"The more carny it got, the better I liked it," King says of his new thriller, Joyland. The book, set in a North Carolina amusement park in 1973, is part horror novel and part supernatural thriller. King talks with Fresh Air's Terry Gross about his career writing horror, and about what scares him now.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on May 28, 2013

Transcript

May 28, 2013

Guest: Stephen King

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Stephen King, has written a new novel. It's got a horror house and a torture chamber, but it's not exactly a horror novel. It's set in an amusement park called Joyland, in 1973. The park's funhouse may be haunted by a ghost, which may explain the dead bodies; but the book isn't exactly a supernatural thriller.

King's new novel, "Joyland," combines elements of crime, horror and the supernatural. The main character is a college student who aspires to write for The New Yorker. After his heart is broken by his girlfriend, he wants to get away from his life in New England; and takes a job in North Carolina at the Joyland amusement park, where he enters a different world.

"Joyland" is published by the small press Hard Case Crime, which publishes new, hardboiled crime novels as well as lost ones from the past, with original cover art in the style of old, pulp-fiction paperbacks. We're going to talk with Stephen King about the new novel, and lots of other things.

Stephen King, welcome back to FRESH AIR. It's really a pleasure to have you back on our show. I would like you to start with a reading from "Joyland," and there's probably an official word for this page. The detective books I used to buy when I was like, in my early teens used to have this kind of page. It's like a page with a lot of like, drama in it. I want you to read that page.

STEPHEN KING: Hi, Terry, it's a pleasure; and this is the tease for "Joyland." (Reading) I stashed my basket of dirty rags and Turtle Wax by the exit door in the arcade. It was 10 past noon but right then, food wasn't what I was hungry for. I walked slowly along the track and into Horror House. I had to duck my head when I passed beneath the screaming skull, even though it was now pulled up and locked in its home position.

(Reading) My footfalls echoed on a wooden floor painted to look like stone. I could hear my breathing; it sounded harsh and dry. I was scared, OK? Tom had told me to stay away from this place, but Tom didn't run my life any more than Eddie Parks did. Between the dungeon and the torture chamber, the track descended and described a double-S curve where the cars picked up speed and whipped the riders back and forth.

(Reading) Horror House was a dark ride but when it was in operation, this stretch was the only completely dark part. It had to be where the girl's killer had cut her throat and dumped her body. How quick he must have been, and how certain of exactly what he was going to do. I walked slowly down the double-S, thinking it would not be beyond Eddie to hear me and shut off the overhead work lights as a joke, to leave me here to feel my way past the murder site with only the sound of the wind and that one slapping board to keep me company.And suppose, just suppose, a young girl's hand reached out in that darkness and took mine.

GROSS: That's Stephen King, reading from his new novel "Joyland." So why did you want to write a crime novel? What do you like about that genre as a reader and as a writer?

KING: When I was a kid, my mother used to read Erle Stanley Gardner Perry Mason mysteries and Agatha Christie's. And I never really cared much for the courtroom drama. The Erle Stanley Gardners and the Perry Masons always seemed even as a kid to be a little bit stylized to me and a little bit fake. But I loved the Agatha Christie.

The thing that I really enjoyed was that it was all there in front of you so that when Miss Marple got everybody together in her room and said this and this and this should have been obvious to me, I'm thinking to myself, well, it should have been obvious to me too. There was a puzzle element to it, and you know, I just couldn't figure out how anybody could plot that way.

And I guess the reason why was because I was never built to be the sort of writer who plots things. I usually take a situation and go from there. So with "Joyland," there is a trail that you can follow that leads to the killer. But you know what - if you figured out who it was in advance, you were doing better than I was because I got near the end of the book before I realized who it was.

GROSS: Uh-oh.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: You might have been in trouble.

KING: No, no, that's good. I think that's good.

GROSS: Is it? Why?

KING: I don't want the reader to feel like this is all a sort of pre-fab creation. I want it to feel organic, to feel like it grew by itself. I've never seen novels as built things. I have a tendency to see them as found things so that I always feel a little bit like an archaeologist who's working to get some fragile fossil out of the ground. And the more you get out unbroken, the better you succeed.

GROSS: So this is a crime novel that's set in an amusement park in North Carolina, but there's also an element of the supernatural in it. What did an amusement park that's kind of very carny seem like a good opportunity to combine crime and the supernatural?

KING: Well, I always wanted to write a novel set in an amusement park, and in the original concept of "The Shining," that was going to be a family that was caretaking an amusement park at the close of the season, and I had sort of an idea...

GROSS: Instead of an old hotel.

KING: Instead of an old hotel, yeah, and I had a title for the book. I was going to call it "Dark Shine," and I think I had a name for the amusement park too. It might have been Skyhook or something like that, named after one of the rides. Ever since I was a little boy and I went to the Topsham Fair, I've loved the rides and the barkers. I think those people in particular, the shy bosses, they're called, they're the people who turn the tips, they're the ones who stand out in front and tell you, you know, everybody wins, folks, everybody wins, come on over, it's just a quarter of a dollar and everybody wins.

Hey Mister, you want to win this big stuffy toy for your girlfriend? She's a beauty and she deserves - you know, that kind of thing. In a way it's a little bit like revival preachers but in a secular version. So I've always been kind of fascinated by those things and in love with it, and I just kind of wanted to visit that world for a while. I had an idea for the story, which by the way has been in my head for about 20 years now.

And all it was to begin with was an image of a boy in a wheelchair, flying a kite on a beach. And that picture was just as clear in my mind as it could be; and it wanted to be a story, but it wasn't a story, it was just a picture, as clear as clear is clear. And little by little, the story built itself around it. And I thought, well, there's an amusement park down the beach from where this kid in the wheelchair is trying to fly his kite. And the name of the amusement park is Joyland.

Then I went to the Internet, which is every writer's newest crutch, and I looked at amusement parks. I wanted one that was nice and clean and sunlit, but wasn't too big. So I didn't want a Disneyworld; I didn't want a Six Flags park. And I settled on a place called Canobie Lake, which is in Massachusetts, just about the right size. [POST-BROADCAST CORRECTION: Canobie Lake is in New Hampshire.]

And I got a map of the place, and I printed it out, and then I started to think, well, this is going to be my funhouse, and it's going to be called Horror House. And this is going to be my Ferris wheel, and it's going to be called the Carolina Spin because it's going to be in Carolina, on the beach there. And little by little, these things came together.

And then as I wrote the book, this thing happened where it became less and less like a standard amusement park, and more and more like the carnies I remembered from my youth; and the more carny it got, the better I liked it, actually. And I started to go to websites that had various carny language, some of which I remembered a little bit, pitchmen called shy bosses and their concessions called shies and the little places where they sold tickets and sometimes sat down and rested were called their dog houses.

And then other stuff I just made up, like calling pretty girls points. I can't remember some of the other ones; it's all mingled together now in my head.

GROSS: My guest is Stephen King. His new novel is called "Joyland." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: My guest is Stephen King. His new novel is called "Joyland." So you mentioned the boy in the wheelchair was the first image that came to you, and that boy in the novel is a 10-year-old named Mike who has muscular dystrophy, but a special kind which usually kills you in your early teens or 20s.

But Mike has the sight. What is the power that he has?

KING: He has a power to see a little bit beyond this world, and he has a very small talent compared to some of the other characters in books that I've written. He's got a little bit of precognition.

GROSS: And his grandfather in the novel is a famous preacher, third to Oral Roberts - and who's the second one you mentioned? Jimmy Swaggart.

KING: Yeah.

GROSS: And his grandfather says that the muscular dystrophy is Jesus' punishment. This preacher is not a generous person.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: He's not an emotionally generous person, and his name is Buddy Ross, and he hosts "The Buddy Ross Hour of Power" on TV. And I'm wondering if you watched preachers on TV when you were growing up and put some of that into this guy.

KING: Yeah, I watched a lot of them when I grew up, mostly because they were always running in the house where my family lived. My mother and my sister had a tendency to turn on people like Oral Roberts, and there was another guy, a real hellfire guy named Jack Van Impe. And I'm aware of people that are sort of in that same ballpark, if you will, in that same church pew today, like Pat Robertson, and they always strike me as a little bit on the shady side, people who are just as interested in making sure they get the collection plate filled as they are in saving souls.

And that's an interesting part of American life, and I've always thought that someday I would really like to write a novel about that kind of guy. And I think the reason that Buddy Ross is not a very sympathetic character in the book is that he never steps onstage in the course of the book. One thing that we do know is that Mike Ross, his grandson, likes him.

He says he's a little bit crazy on the Jesus stuff, but otherwise he seems like a pretty nice guy. And that's one thing about the characters in the stories I write. I always try to show that we all have our good side. Sometimes with some people it's very small, but it's usually there.

GROSS: Did you watch Oral Roberts for religion or for entertainment value?

KING: Mostly for entertainment and also because of the rhythm of speech. I enjoyed all those revival preachers because there's a certain poetry in the way that they speak, and I always enjoyed that. I know W.H. Auden said thou shalt not read the Bible for its prose, and I suppose you're not supposed to watch televangelists to enjoy the sound of their voice, but man, sometimes it's hard not to.

GROSS: Are you trying to make a connection in your book between the preaching that you say ends with the collection of the plate and the kind of carny pitchman?

KING: Yeah, I think it's there. It isn't overt in the book, but sure. We have a lot of carny aspects to life in America, everything from television and the movies to our religion, and we can see from the mega-churches that, my goodness, Terry, people love a show, so that you can have a nice Methodist church somewhere in Oak Park, Illinois if you want, and people are going to come, and they're going to sit there, and the organ's going to play. And that's all terrific. But what I want is down in the amen corner, Jesus jumping, I want that big choir with the people swaying from side to side, oh God, and I want the electric guitar. Then I want the preaching, you know, where the guy's going to walk back and forth and not just stand like a stick behind the pulpit. He's going to, you know, shake his fist a little bit in the air and then he's going to smile and throw his hands up and say God's good, God's great, can you give me hallelujah.

I just absolutely adore that, and it's really only about two steps from the carny pitchmen, because I like that, too.

GROSS: Is that what you had in church? What did you have in church when you were growing up?

KING: Oh no, I went to a Methodist church for years as a kid, and Methodist youth fellowship on Thursday nights, and it was all pretty - you know, think of a bottle of soda with the cap off for 24 hours.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: There weren't very many bubbles left in that stuff by then. It was pretty - it was Yankee religion, Terry, and there's really not much in the world that's any more boring than that. They tell you that you're going to go to hell, and you're half-asleep.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: What kind of preaching is that?

GROSS: But you always believed in God. You were just bored in church.

KING: Well, I guess that the jury's out on that.

GROSS: About, about which? About God?

KING: On God and the afterlife and all that. It's certainly a subject that's interested me, and I think it interests me more the older that I get. And I think we'd all like to believe that after we shuffle off this mortal coil, that there's going to be something on the other side because for most of us, I know for me, life is so rich, so colorful and sensual and full of good things, things to read, things to eat, things to watch, places to go, new experiences, that I don't want to think that you just go to darkness.

I can remember as a kid thinking to myself, oh God, I hope I don't die because I'll just have to lie down there in that box and I won't be able to play with my friends or go to baseball games or any of those things. As a kid, death seemed boring to me. As an adult, I think that it seems more like a waste of everything. Somebody once said every time a professor dies, a library burns.

And there's some of that feeling. But as far as God and church and religion and the Buddy Rosses and that sort of thing, I kind of always felt that organized religion was just basically a theological insurance scam where they're saying if you spend time with us, guess what, you're going to live forever, you're going to go to some other plain where you're going to be so happy, you'll just be happy all the time, which is also kind of a scary idea to me.

GROSS: I remember you telling me the last time we spoke that you always believed in God, and it's a choice that you made, and you just, you choose to believe it.

KING: I choose to believe it, yeah. I think that - I think that that's - I mean there's no downside to that, and the downside - if you say, well, OK, I don't believe in God, there's no evidence of God, then you're missing the stars in the sky, and you're missing the sunrises and sunsets, and you're missing the fact that bees pollinate all these crops and keep us alive and the way that everything seems to work together at the same time.

Everything is sort of built in a way that to me suggests intelligent design. But at the same time there's a lot of things in life where you say to yourself, well, if this is God's plan, it's very peculiar. And you have to wonder about that guy's personality, the big guy's personality. The thing is, like, I may have told you last time that I believe in God. What I'm saying now is I choose to believe in God, but I have serious doubts.

And you know, I refuse to be pinned down to something that I said 10 or 12 years ago. I'm totally inconsistent.

GROSS: I'm all for that.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Really. So is your interest in the supernatural connected to your interest in or questioning of God? Because they're both in some way about powers beyond our perception.

KING: Well, belief in the supernatural or belief in wild talents like precognition and telepathy and telekinesis and things like that, it seems to me that belief in those things is just very, very freeing. I can remember talking to the late Stanley Kubrick, who called when he was getting ready to start filming "The Shining," and whatever else you could say about him, he was a thinking cat.

You know, he really thought about what he was doing. He didn't just go out there and shoot film. So he said to me, Stephen, don't you feel that anybody who tells a ghost story is basically an optimist because that presupposes the idea that we go on, that we go on into another life? And I said, well, yes, I can see that, but what about hell?

And there's this long pause on the other end of the line, and then Stanley Kubrick said in this very stiff voice: I don't believe in hell.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: And to me it was the voice - to me it was the voice of somebody who was denying their own maybe deeply held belief in something that they were unable to root out. You know what the Catholic Church used to say: Give them to me when they're young and they're ours forever. And there might have been some of that in Stanley Kubrick's voice.

GROSS: It sounds very selective to decide to like believe in heaven but not hell.

KING: Yeah, I know. Well, it doesn't seem quite fair, does it? It's like only allowing one team to have their batters-ups in a baseball game. So he said I don't believe in hell, and I said no, you choose not to believe in hell. And that was the only time I ever really spoke to him on subjects theological.

GROSS: Back to the question of whether your interest in the supernatural connects to your thinking about God, and some people I know will hate this question, I'm not trying to compare God to the supernatural. However, they're both about a belief in things beyond our powers of perception.

KING: Well, you have every right in the world to connect God to the supernatural because God is a tripartite being, and one of his beings is the Holy Ghost. We've rearranged that in our minds. I'm sure that Cotton Mather would be rolling over in his grave. So now that you go to church, and they'll say Holy Spirit, which comes down to the same thing, but to me that's a milk water way of saying what was the original Christian translation of that: God is a ghost, God is a holy ghost.

And he's there, supposedly, and watches what we do, and he is sort of the ultimate, what can I say, spook, because he's there. He watches you while you're doing this, while you're doing that. And I can remember actually being in a Boston movie theater about 12 years ago or so, going to the bathroom in the middle, and going into one of those stalls in the movie theater bathroom, and there were posters on all the inside of the stall doors that had Jeff Goldblum from "The Fly."

And it had this caption that said: Jeff Goldblum is watching you poop.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: And he had this horrible, intense look in his eyes, and I was thinking, well, it isn't Jeff Goldblum that's watching us have sex with people that we're not in relationships with, or stealing stuff or this or watching us poop. It's God. So that is basically a supernatural theme. I have no problem with collating those two things together.

GROSS: Stephen King will be back in the second half of the show. His new novel is called "Joyland." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with Stephen King, who's famous for his horror novels and stories of the supernatural, including "Carrie," "The Shining," "The Stand," "The Dead Zone" and "Cujo." A new CBS summer TV series adapted from his novel "Under the Dome" premieres June 24th. His new novel is called "Joyland."

When you were in your formative years, what were your supernatural fears, and did you always wish you had some of the supernatural powers that you've given some of your characters?

KING: I think it's built-in. I think it's just part of human nature. I've been queried a lot about where I get my ideas or how I got interested in this stuff. And at some point, a lot of interviewers just turn into Dr. Freud and put me on the couch and say: What was your childhood like?

And I say various things and I confabulate a little bit and kind of dance around the question as best as I can, but bottom line: My childhood was pretty ordinary, except from a very early age, I wanted to be scared. I just did. I was scared afterwards. I wanted a light on, because I was scared that there was something in the closet. My imagination was very active, even at a young age.

For instance, there was a radio program at the time called "Dimension X," and my mother didn't really want me to listen to that, because she felt it was too scary for me. So I would creep out of bed and go to the bedroom door and crack it open. And she loved it, so apparently, I got it from her. But I would listen at the door, and then when the program was over I'd...

(LAUGHTER)

KING: ...I'd go back to bed and quake.

GROSS: So you wanted to be scared, or, I mean, did you have a...

KING: Yeah.

GROSS: ...avoidance thing with being scared? Or did you just want to be scared?

KING: Terry, I loved it. It was a classic attraction-repulsion thing. I wanted to be scared. I wanted that reaction. And, I mean, I can self-analyze to a degree, and it might be right and it might be wrong. But here's what I really think: I wanted an emotional engagement with something that was safe, something that I could pull back from. And I basically, I had a big imagination, I wanted to put it to work, even at an early age.

So I would ask my mother to take me to movies like "Earth vs. the Flying Saucers" or "Them," where the giant ants came out of the subway drains in Los Angeles. And she was OK with that. She was down with that, because she liked it. I can remember her reading us - my brother and I - "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde." We would get the classics comic books with things like "Oliver Twist." And "Oliver Twist" was a wonderful story, but what I really liked was the death of Fagan, where, you know, he was just sort of ah, with his eyes bugging out, because the classics comic books, in a lot of cases, were just dressed-up easy horror comics. So I think it's built in. I think it's like a piece of magnetic steel that draws a needle.

GROSS: Are there things that scare you as an adult that you were not aware enough of or smart enough for when you were a kid to understand that these were frightening things?

KING: Well, you grow up, and you become frightened of different things, and they have a tendency to be real-world things.

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: It's been quite a while since I was really afraid that there was a boogeyman in my closet, although I am still very careful to keep my feet under the covers when I go to sleep, because the covers are magic, and if your feet are covered, it's like boogeyman Kryptonite.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: So I'm not as afraid of that as I used to be. The supernatural stuff doesn't get to me anymore. But here's the movie that scared me the most in the last 12 or 13 years: The movie opens with a woman in late middle-age, sitting at a table and writing a story. And the story goes something like, then the branches creaked in the - and she stops, and she says to her husband: What are those things? I can't think of them. They're in the backyard, and they're very tall, and birds land on the branches. And he says, why, Iris, those are trees. And she says, yes, how silly of me. And she writes the word, and the movie starts. That's Iris Murdoch, and she's suffering the onset of Alzheimer's disease.

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: That's the boogeyman in the closet now.

GROSS: Why is that the thing you're most afraid of?

KING: I'm afraid of losing my mind.

GROSS: Losing your memory?

KING: Mm-hmm. Well, you don't just lose your memory. You lose your mind, basically.

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: You lose your identity, your sense of who you are, where you are. If you're a block away from the house, you may forget how to get home. I think I could put up with a lot of things and a lot of pain. I have put up with a lot of pain. I got hit by a car in 1999 and got most of the bones on the right side of my body broken, and I bore up under that and I got better. But you can't get better if your mind is stolen away from you.

So here's what I'm saying: As we get older, our fears, in some way, sharpen and become more personal, because we can no longer - let's say take a book like "It" or maybe "Christine," and say these are make-believe fears. Instead, we have more of a tendency to focus on things that we know are out there. We fear for our families. We fear for our mental abilities. We fear for diseases.

You may see a dark spot on your arm or an irregular mole and say, gee, I better get that checked out. If you're woman, doing a self breast exam and you feel a lump that wasn't there before, these are very real fears. So when you ask me what I'm afraid of, I'd say I still go to see ghost movies when I get a chance or some sort of supernatural being, that kind of thing, but it doesn't scare me as it scared me when I was a child. But on the other hand, if I see a wonderful writer like Iris Murdoch losing her mind, I have more of a tendency to focus on that than how loving her husband was, which is supposed to be the uplifting part of that film.

GROSS: My guest is Stephen King. His new novel is called "Joyland." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Stephen King, and his new novel is called "Joyland." And it's published by the crime press, Hard Case Crime.

So, you know, you mentioned your car accident from 1999. Are you still in chronic pain as a result of that?

KING: I guess I am, but I don't think about it very much anymore. I exercise a lot, and I try to stay as mobile as I possibly can. I can remember the doctor saying to me, well, after the accident I asked the guy: Will I ever be able to play tennis again? And he said no, but you'll be able to walk. Well, I can play tennis again, and I think that...

GROSS: Wow. Really?

KING: Well, you know it...

GROSS: I mean, your leg was crushed, basically.

KING: It was crushed. But I think that doctors have a tendency to lowball, so that if you get a little more than they say, you say, wow. I'm really beating the odds here. I'm doing a terrific job. But you just go ahead and you do the therapy and you bear the pain, because you're told that if you do the therapy and bear the pain, things will get better. And that actually seems to be the case.

GROSS: So one time when we spoke after the accident, you were saying, you know, you had had an addiction problem with pills, and you'd kicked that. You were clean. And then you're in this horrible accident and you're own painkillers that are addictive. And as much as you wanted to not take them, like, after a certain kind of accidental like the one you are in, you really need help.

KING: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: You really need painkillers. So were you able to successfully get off of them?

KING: Yeah. This was - I had the accident in 1999, and at that time, Oxycontin hadn't been on the market very long - two years, maybe three. You could check me on that, but it wasn't a long time. And I was a mess, Terry. I mean, the muscles were just hanging off what remained of my leg, and they talked very seriously about amputating the leg and ended up doing something called a fasciotomy instead that let out just enough of the blood and the swelling so that I could keep the leg. But it was broken everywhere. You couldn't even count the brakes.

He said that - the doctor that worked on me said it was like marbles in a sack. And the pain was terrible, and they said, you know, we have this wonderful drug called Oxycontin, and we think that it's going to be a game-changer for you. And it was. And I loved that stuff. I loved the fact that I was able to finish the book that I had been working on, called "On Writing."

The pain was terrible, but the pills made the pain better. They helped the physical pain, but they also cheered you up the way that...

(LAUGHTER)

KING: ...addictive drugs do. So by, I would say, two years down the road, post-accident, I was a total junkie again. I was using probably somewhere between 280 and 400 milligrams of Oxy a day, and my leg hurt as bad as it ever did, because your brain basically wants that dope and refers the pain or creates the pain so that you'll continue to get it.

And finally, that just had to stop. That's all. And I kicked it. And it's not, for anybody out there who's doing Oxy, who thinks you can't kick it, you absolutely can. It's a three-week process. It's a physical process where you shiver and shake. They don't call it kicking the habit for nothing. But when it's done, it's done, and there's no residual urge to use that I ever felt. So I've been clean - totally clean for a long time now.

GROSS: Do you think your writing has changed, or what you want to write about has changed in the years since the accident?

KING: I don't know. I'm on the inside.

GROSS: Because at first you said you weren't going to write for a while, but, you know, you're still writing.

KING: Yeah. But the thing is, when I said that I wasn't going to write or when I was going to retire, I was doing a lot of Oxycontin for pain, and I was still having a lot of pain. And it's a depressive drug, anyway, and I was kind of a depressed human being because the therapy was painful. The recovery was slow, and the whole thing just seemed like too much work. And I thought, well, I'll concentrate on getting better, and I probably won't want to write anymore.

But as health and vitality came back, the urge to write came back. Now, here's the thing: I'm on the inside, and I am not the best person to ask if my writing changed after that accident. I don't really know the answer to that. I do know that since then I've - that was close. That was really being close to stepping out, the accident. And a couple of years later, I had double pneumonia. And that was close to stepping out of this life, as well. And I think you have a couple of close brushes with death like that. It probably has...

(LAUGHTER)

KING: Somebody said the prospect of eminent death has a wonderful clarifying effect on the mind. And I don't know if that's true, but I do think it probably causes some changes, some evolution in the way a person works. But on a day-by-day basis, I just still enjoy doing what I'm doing.

GROSS: Since, you know, we've talked a little bit about your interest in the supernatural and in whether or not there is an afterlife, did you have any of those, you know, like near-death experiences that are, you know, sometimes described by people who came very close to dying, but were then revived?

KING: I never saw the white light. I'm sorry. I can't tell a lie. I never saw the white light. So, no, I can't say that I've ever had a near-death experience where, you know, angels rose fluttering from the end of my hospital bed or anything. I just felt really sick, and I had a couple of - my wife would say - bad drug interactions where I started to rave. And I don't remember any of those things. And that's it, man. I'm just glad to be alive now, and I'm very curious about what, if anything, comes next. But I'll wait. I'll wait.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I hope you'll be waiting a really, really long time.

KING: Yeah. From your lips to God's ear.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: If there is a God, right?

(LAUGHTER)

KING: If there is a God.

GROSS: So...

KING: What do you think, Terry? Is there, or is there not?

GROSS: Oh, I'm not even - I'm not going there.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: You're not even going there.

GROSS: It's my show. I don't have to go there.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: That's right. I have to go there, because I have to promote my book. And because I have to promote my book, I have to talk about whether or not I think there's a God. Well, I just don't know, actually.

GROSS: I think that's a fair bargain, don't you?

KING: Yeah.

GROSS: You've got a book, and you've got to answer that question.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: That's right. You know, the whole thing is a little bit like a carnie, isn't it? The whole book promotion deal or the movie promotion deal. You do this thing, and it's inside the tent. So then you have to kind of come out and do a little cooch dance to get people to come inside.

GROSS: I know. I know. I know you must feel that way. From my point of view, on the other side of the mic, this is, like, this is my chance to talk to you about things I'd love to talk with you about. And I know the reason why you're here is that you've got a book to promote. But to me, it's like what a wonderful opportunity to have this conversation.

KING: I don't mind. I mean, people generally go in a barbershop or in a diner and get a cup of coffee and start talking about these things. And it's kind of like, hey, see you later. I've got a job to do. But this is your job and my job, so I get to talk about all these things. It's kind of cool.

GROSS: I want to point out to our listeners the cover of "Joyland" - which is your new crime novel on the Hard Case Crime press. First of all, I want to ask you - this is not - you're the kind of successful writer that can get a really large advance for a book. I doubt Hard Case Crime can pay you the kind of advance that you get because, I mean, they're this really little press devoted to a certain type - like a certain niche of, like, the hard-boiled crime novel. They love those, like, old-fashioned pulp covers. Your book has one of those.

KING: Yeah.

GROSS: They do, like, original paperbacks and I think some, like, republications of paperbacks. Why did you want to write for them? It's not going to be - you know, it's not going to be your biggest moneymaker. Because of...

KING: It's - it - Hard Case Crime is a throwback to the books that I loved as a kid. We lived way out in the country and my mother would go once a week shopping and she would go to the Red and White or the A&P to pick up her groceries. And I would immediately beat feet to Robert's Drug Store where they had a couple of those turnaround wire racks with the hardboiled paperbacks that usually featured a girl in scanty clothing on the front.

She'd usually, you know, be kind of dressed like a cigarette girl and it'd be a Lucky Strike hanging from one corner of her mouth. And she'd have an automatic pistol in her hand.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: The teaser line that I always loved the most was for a novel called "Liz," where it said: She hit the gutter and bounced lower.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That's great.

KING: I love that. And, you know, the one on the front of "Joyland" says: Who dares enter the funhouse of fear?

GROSS: And I want to mention there's a teaser line. There's a limited edition hardcover version of the book though the book is largely paperback.

KING: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And the teaser line on the hardcover version is: Beyond the lights, there is only darkness. I like that.

KING: I wrote that line.

GROSS: Did you? I like that.

KING: Yeah, I wrote that line.

GROSS: And that's the lights of the amusement park that it's set in.

KING: What is it? Beyond the light there's only darkness.

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: Read the line again.

GROSS: You like it that much you want to hear it again? OK.

KING: I didn't hear the end of it.

GROSS: Beyond the lights there is only darkness.

KING: Can I write or what? God.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: Just kidding.

GROSS: Stephen King, I want to thank you so much for talking with us. It's really been great to talk with you again. And I'm so glad to hear that, in spite of the car accident, like, you're playing tennis and stuff like that. That's great.

KING: Yeah. Yeah, it's good to be alive, Terry. And some time when you're up here we'll play doubles.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Oh. Yeah. I'll tell you who will win that one.

KING: How about shuffleboard? Maybe shuffleboard.

GROSS: That's right. And ping pong.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: Pac Man.

GROSS: Pac Man. Even better.

KING: It's been a pleasure. Thank you so much.

GROSS: Thank you so much. Be well. Stephen King's new novel, "Joyland," will be published June 4th. You can read an excerpt and see both book covers on our website freshair.npr.org. Next week is also the release date for a new CD of songs from King's music theater collaboration with John Mellencamp called "Ghost Brothers of Darkland County" and a new CBS summer TV series adapted from King's novel "Under the Dome" premiers June 24th.

Coming up, Ken Tucker reviews Vampire Weekend's new album. This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: The band Vampire Weekend has released its third album called "Modern Vampires of the City." The band's chief lyricist, singer Ezra Koenig, has said that he's come to think of this new album as the third of a trilogy about growing up and maturing. Rock critic Ken Tucker has a review.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "OBVIOUS BICYCLE")

EZRA KOENIG: (Singing) Morning's come. You watch the red sunrise. The early day still flickers in your eyes. Oh, you ought to spare your face the razor because no one's going to spare the time for you. No one's going to watch you as you...

KEN TUCKER, BYLINE: Vampire Weekend is the New York City quartet that has carved out its own sense of immaculate melancholy for our era as surely as Steely Dan once did for Upstate New York in the '70s. Vampire Weekend, characterized most immediately by the earnest, concise, but sometimes surprisingly expansive vocals of Ezra Koenig, makes atmospheric music. The atmosphere is one that calls attention to confusion, doubt and a feeling of purposeful aimlessness, all presented within exceedingly well-crafted choruses and precisely metered lyrics.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "DON'T LIE")

KOENIG: (Singing) One look sent knees to the ground. Young bloods can't be settling down. Young hearts need the pressure to pound. So hold me close my baby. Don't lie. I want him to know God's love's dying. Is he ready to go? It's the last time running through snow where the vaults are full and fire explodes. I want to know, does it bother you? The low click of the ticking clock. There's a lifetime right in front of you. And everyone I know.

TUCKER: Throughout this album there are nods and bows - but never full commitments - to religion and a spiritual life. The way the singer asks to be held in your everlasting arms; the way he fetishizes a crucified or satanic red right hand in a song called "Worship You"; the way they deploy the Latin phrase for "to God"; the way he gets a thrill, in "Unbelievers," that only an invocation of the unearthly harmony of the Everly Brothers can do proper justice.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "UNBELIEVERS")

KOENIG: (Singing) Got a little soul. The world is a cold, cold place to be. Want a little warmth but who's going to save a little warmth for me? We know the fire awaits unbelievers, all of the sinners the same. Girl, you and I will die unbelievers bound to the tracks of the train. If I'm born again I know that the world will disagree. Want a little grace but who's going to say a little grace for me?

(Singing) We know the fire awaits unbelievers, all of the sinners the same. Girl, you and I will die unbelievers, bound to the tracks of the train. I'm not excited...

TUCKER: Ultimately, however, the quest pursued on "Modern Vampires of the City" is not a religious one so much as a venture that Vampire Weekend makes to musically invoke the grandeur of pop. The big, booming drum sound that predominates here, the jittery and sometimes organ-like keyboards, these are sounds rooted in the comforts of pop history that provide Vampire Weekend with its secular faith.

This is an album that finds sustenance in invoking songs ranging from Desmond Dekker's "Israelites" to The Rolling Stones' "19th Nervous Breakdown." It finds release in periodic explosions of rock 'n' roll.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG)

KOENIG: (Singing) You torched a Saab like a pile of leaves. I'd gone to find some better wheels. Four five meter running around the bend when the government agents surround you again. If dying young won't change your mind, then you're baby, baby, baby right on time. Out of control but you're playing the role. You think you can go to the 18th hole. Or will you flip-flop the day of the championship? Try to go it alone on your own for a bit.

(Singing) If dying young won't change your mind, baby, baby, baby, you're right on time.

TUCKER: Like the New York-based, Whit Stillman-directed films that have frequently seemed like the cinematic predecessors to Vampire Weekend's post-prep-school music, these guys make eloquent, plaintive noise about the fellowship of people sharing their breakdowns with each other, and exchanging precisely worded jokes about the vulgar challenges of modern life. They don't find their redemption in communal worship so much as they do in the company of clever, yet fundamentally sincere people such as themselves.

GROSS: Ken Tucker reviewed "Modern Vampires of the City," the new album from Vampire Weekend. You can download podcasts of our show on our website, freshair.npr.org. And you can follow us on Twitter @nprfreshair and on Tumblr at nprfreshair.tumblr.com.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.