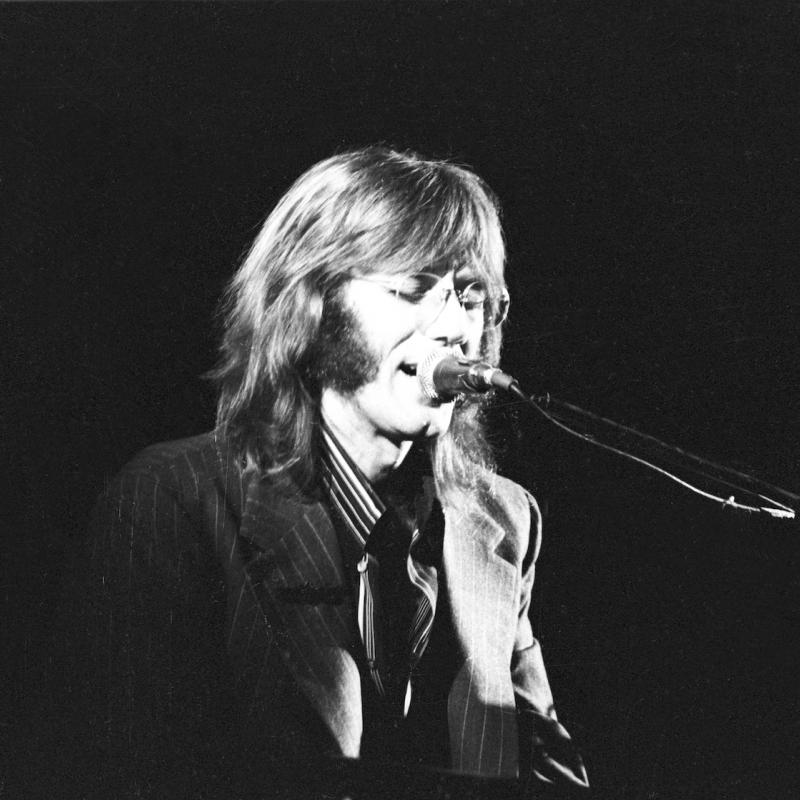

Singer and songwriter John Fogerty

We spoke with him on the occasion of an album releasethe double CD concert album Premonition. Featured on the recording is many of his biggest hits with Creedence Clearwater Revival: "Who'll Stop the Rain," "Down on the Corner," "Bad Moon Rising," and "Proud Mary." Fogerty won a Grammy Award in 1997 for his album Blue Moon, Swamp

Other segments from the episode on September 2, 2002

Transcript

DATE September 2, 2002 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: John Fogerty, lead singer of Creedence Clearwater

Revival, talks about the history of the band and about his

songwriting

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Today we conclude our series on pop and

rock of the '60s.

John Fogerty was the lead singer and songwriter with the band Creedence

Clearwater Revival. Between 1968 and '72, the year Creedence broke up, they

had several gold records, as well as eight top 10 singles, including "Proud

Mary," "Bad Moon Rising," "Green River," "Down on the Corner" and "Lookin' out

my back door." For many years, Fogerty refused to perform the songs that made

him famous because his old record company owned the rights to those songs.

But in 1998, he returned to those songs on a live CD called "Premonition." I

spoke with him in '98 when "Premonition" was released. Before we hear from

Fogerty, let's listen to one of Creedence Clearwater's signature songs.

(Soundbite of music)

CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL: (Singing) Now when I was just a little boy,

standin' to my daddy's knee, my papa said, `Son, don't let the man get you and

do what he done to me.' 'Cause he'll get you, 'cause he'll get you now, now.

And I can remember the Fourth of July, runnin' through the backwood, bare.

And I can still hear my old hound dog barkin', chasin' down a hoodoo there,

chasin' down a hoodoo there.

Born on the bayou, born on the bayou, born on the bayou. Lord, Lord...

GROSS: You've written a lot of songs inspired by the South, like "Born on the

Bayou." You were actually born in El Cerrito, California, near Berkeley, and

I'm wondering why in some of your songs you wrote first person, in the persona

of a Southerner.

Mr. JOHN FOGERTY (Singer/Songwriter): Gee, that's a good question. I think I

was trying to place myself in this mythicized and romanticized territory.

It's a mythical world, kind of, that I created. Certainly musically, it's a

mythical world, and why I used the device of first person, I think--well, to

say it another way, I think I realized that talking about the main street of

El Cerrito probably wasn't going to be something that was widely understood or

even cared about. It didn't seem very interesting to me, anyway, and the

South has always fascinated me, and that's really the reason, but--the reason

that I placed myself that way in my own songs--but if you want to ask me why

am I so fascinated about the South, I really have to confess I don't know.

GROSS: Because of the music?

Mr. FOGERTY: Most of what I know about the South came through music,

particularly the early forms of rock 'n' roll, meaning rhythm and blues,

country blues and country music. And again, all those versions, I believe,

were pretty romanticized. You know, they were sort of rainbow-colored visions

of the South, in most cases.

GROSS: Would your father have ever said what the father says in "Born on the

Bayou": `Papa said, "Son, don't let the man get you and do what he done to

me'?

Mr. FOGERTY: Yeah, he did say that a few different ways. My dad was a

dreamer, unfortunately. He wasn't much of--he didn't find great success in

this world, but he was quite a dreamer, and pretty literate. He read all the

time, and he was inspired by all kinds of people that he passed on to me in

kind of little snippets. I can remember when I was very, very young, my

father reading the story of "Dangerous Dan McGrew" over and over. He loved

that particular poem. He really loved Ernest Hemingway. You know, he was a

product of the '30s and '40s, I guess. My parents certainly were

Depression-era people, and I learned a lot of those lessons at their knee, and

I think just by the way my dad ended up living his life, just by example,

really, he was telling me `Don't let the man get you and do what he done to

me.'

GROSS: John Fogerty, do me a favor. Can you say two words for me--`turning'

and `burning'?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, when I'm sitting here quietly in a library atmosphere, it

is `turning' and `burning,' but when I sing, it always comes out `toinin' and

`boinin.'

GROSS: Yeah. I know. That's very New Orleans, isn't it?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, you know what? I didn't know where, really, although

I've noticed--because I just did it naturally. When I wrote the words, I

wrote them to sound that way.

GROSS: And the song in question is "Proud Mary." Yeah.

Mr. FOGERTY: Right. I've also noticed, though, that Howlin' Wolf has very

much that sort of dialect in his music. I only spoke to him a couple of

times, but in his singing, you know, in the great songs that he did, he

pronounces those words that way. But yes, down in New Orleans, a lot of

people will say `toinin' and `boinin.'

GROSS: Well, why don't we pause here and listen to your new recording of

"Proud Mary" from your new album, "Premonition"? My guest is John Fogerty.

(Soundbite of cheering, applause and music)

Audience: One, two, three, four!

Mr. FOGERTY: (Singing) Left a good job in the city, workin' for the man

every night and day. And I never lost a minute of sleeping worrying about the

way things might have been.

Big wheel keep on turnin', Proud Mary keep on burnin,' rosin', rollin',

rollin' on a river.

Been a lot of places in Memphis, umped a lot of babes down in New Orleans,

then I never saw the good shot of a city till I hitched a ride on a riverboat

queen.

Big wheel keep on turnin', Proud Mary keep on burnin,' rollin', rollin',

rollin' on a river.

GROSS: The members of Creedence started performing together, I think in 1959,

when you were all in high school. Do I have that right?

Mr. FOGERTY: That's correct. Actually, we were still in the eighth grade,

three of us.

GROSS: Junior high school.

Mr. FOGERTY: Right.

GROSS: What were your early songs? What was the band like back in eighth

grade?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, we were mostly an instrumental band. I patterned myself

and my band very much around Duane Eddy, and we did several Duane Eddy

instrumentals. We also had probably 10 or more instrumentals that I had

written, not remarkably original, really, but you know, they were--I would

play--taking the pattern, basically, from Duane, I would play the melody on

the guitar and Stu, who was not yet playing bass, was playing piano, and I had

kind of showed him the rudiments of, you know, three-note chords and a little

bass line, so, you know, at that level of our development, we were certainly

learning the rudiments of music, but always with a rock 'n' roll flair, you

might say.

Rock 'n' roll has some pretty strict parameters that when you step outside

0those parameters, everyone kind of gives you that cross-finger look, like

they're holding back a vampire. So, you know, I've always kind of based

everything from the center of rock 'n' roll.

GROSS: The band's first name was Tommy Fogerty--Tommy Fogerty, that's your

brother--Tommy Fogerty & The Blue Velvets. And then the band was called--what

was the second name?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, actually originally, the three of us were the same age,

in the eighth grade, so we were just The Blue Velvets.

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. FOGERTY: And then we got the lucky happenstance to make a few records

for a little local Bay Area label, and under that guise, Tom would join us.

Tom, by that point I think was out of high school and of course, we were still

in high school, and you know, under that recording name we were Tommy Fogerty

& The Blue Velvets.

GROSS: Then what was the next name that you used?

Mr. FOGERTY: The next name on records was The Golliwogs.

GROSS: And what was The Golliwogs supposed to mean?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, this is one of those deals because you're young and

everybody else is supposedly older and wiser, and it's their record company.

The real story is, we worked on the first single, the first song for about

nine months. I mean, we had gone in there and recorded it, and we kept

pressuring the record company, `When's it coming out? When's it coming out?'

This is all of 1964. And then finally, they tell us, `Well, the record's

here. The pressings are here.' So we rush over--actually, I rushed over to

San Francisco and I pull one--you know, it's your first real record on a

supposedly national label, Fantasy Records, and you want to look at this

thing. And you take it out of the box and I looked at it and, oh, my God, it

said The Golliwogs.'

So Max was one of the brothers that owned the company then, and I said, `Well,

jeez, Max, there's a mistake here. There's like a typo. They put The

Golliwogs.' `No, we decided to rename you guys.' `Oh. Well, why?' `Uh, see, a

golliwog is--in England, a golliwog is like a voodoo doll. It's this doll

that comes from Africa. It's really a hip thing. It's really cool, and it's

black, too. It's like from the black culture, and it's really cool. It's

like a voodoo doll, and in England, it's really a hip thing.' Of course, in

1964, the British had arrived in America, and all things English and British,

mod, etc., were very cool. Unfortunately, no one in England had ever heard of

a golliwog, either.

GROSS: My guest is John Fogerty, formerly the lead singer of Creedence

Clearwater Revival. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL: (Singing) Oh, Suzie Q, oh, Suzie Q...

GROSS: This is the final edition in our series on rock of the '60s. Let's

get back to our 1998 interview with John Fogerty, the former lead singer of

Creedence Clearwater Revival.

How did you come up with the name Creedence Clearwater Revival?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, of course, after struggling under that name for several

years, the ownership of Fantasy changed, and the very first thing we wanted to

do was change our name, and the guy that had bought the company, the new owner

of the company, agreed with us that we could change the name. I think he

hated it, too. And so we sat about for many months trying to come up with a

name, but none of it was very suitable or remarkable. The whole process

started to bog down, I think.

It was Christmas Eve and I was watching television, and two commercials came

on television, one of which was a beer commercial that really promoted its use

of the water, and they were showing this lush, green woods and this flowing

river, and you know, the place looked enchanted, and there was this beautiful

music in the background. And right after that was a black-and-white

commercial. It was an anti-pollution commercial, and it showed all kinds of

pollution and garbage in the water and that sort of thing. And at the end, it

said, `If you want to change things, write to Clean Water, Washington.' And I

was really taken by the two things, back to back, the beautiful clear water

and the, you know, terrible polluted water, and clean water stuck in my mind;

I started playing with that. Clean Water didn't seem like a very good name

for a band, but I evolved to Clearwater, and I remembered back to when we had

toyed at some point with the name Creedence.

It's not true that I ever knew this person. We did know of a man whose first

name was Creedence--pretty unusual name--and of course, I shuffled that

around. Clearwater Creedence, Creedence Clearwater. Oh! I kind of like

that. But it still didn't sound complete. Remember, this is during the era

of Jefferson Airplane and Strawberry Alarm Clock and Buffalo Springfield. So

I kept playing around with different words and I thought that what we were

really doing was having a revival, the group. We had been together a long

time, but we were now experiencing a revival, or at least I hoped so. So

finally after about probably 10 minutes of thought or even less, I had come up

with the name, and I must say that the name was much better than we were at

the time.

GROSS: Creedence Clearwater Revival had its biggest hits between 1968 and

1972, a bunch of top 10 hits, and you were based in the Bay Area, around San

Francisco. San Francisco at that time was dominated, you know, in the public

mind by groups like the Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead, the kind of

psychedelic bands. Where did you see Creedence fitting into that California

scene of the time?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, since I had grown up so much with fondness for blues and

R&B and particularly rock 'n' roll, my work ethic, you might say, was somewhat

different than what I perceived the work ethic, if you can even use that term,

of people like The Grateful Dead, and so I noticed that our music, or our

approach to music was--or at least mine--was far different than the other

bands that were becoming famous in San Francisco. But politically, I felt

very much as part of the feeling of people in the Bay Area or San Francisco,

or really my generation in general.

GROSS: You wrote some politicized songs that pertained to the draft and to

the war in Vietnam, like "Fortunate Son," which is a song about how privileged

people make wars, but the sons of the privileged are exempt from fighting

them. And "Who'll Stop the Rain" I think was perceived as an anti-Vietnam

song. I know you were in the reserves for a while. How did you end up in the

reserves?

Mr. FOGERTY: I was a very lucky guy, really. A local sergeant in a reserve

unit took pity on me and basically let me join his unit when, you know, the

unit was full and there was really no place for me to go. He basically took

pity on me and let me get into his reserve unit at the time.

GROSS: So what year was that, that you were drafted?

Mr. FOGERTY: 1966.

GROSS: So you were already recording then.

Mr. FOGERTY: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: And you didn't want to go to Vietnam, so you ended up in the reserves.

I'm wondering if being in the reserves affected your attitude toward the war

or toward the kinds of songs you wanted to write.

Mr. FOGERTY: Oh, I would say very much, because you know, you quickly learn,

when you become a grunt in the military, that you're just a number. You're

just a piece of meat. You're nothing. You have no rights, you have no

privileges, you have no power over what happens to you, and that's a very

debilitating feeling, and I can remember--You know what? I can remember the

night I finally arrived at my boot camp after being shuffled around for a

couple of days, really, and it's your first day, and they keep you awake

forever, you seem like you've been awake, and somewhere around midnight or 1

in the morning, I know all my guys got marched off to get our hair cut, and

you kind of come back, you feel like you've been sexually abused, you know.

They say, `OK, go back in there.' And you go back in your barracks and

there's like 30 other people in the same boat, and you're all a bunch of ugly

eggheads. And I laid down on my bunk and I must confess, my eyes certainly

watered, is I guess what I'm trying to say. Of course, you get over that,

because you're supposed to be a man. It was probably the most forlorn feeling

I've ever had.

GROSS: Did you see your song "Who'll Stop the Rain" as an anti-war song?

Mr. FOGERTY: Yes.

GROSS: Do you want to say anything about writing this song before we hear it?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, of course, the rain is a metaphor for the gobbledygook

that comes down from the places on high, and I was feeling pretty much

powerless at the time I wrote this song, and I was trying to reflect that

really it has gone on since the beginning of time, and even at the time of the

Vietnam War, when there was so much protest in the air, I had a very

fatalistic point of view. It seemed like all the protesting in the world

wasn't going to change anything.

(Soundbite of music)

CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL: (Singing) Long as I remember, rain's been

comin' down, clouds of mystery pourin' confusion on the ground. Good men

through the ages, tryin' to find the sun, and I wonder, still I wonder, who'll

stop the rain?

I went down Virginia, seekin' shelter from the storm. Caught up in the fable,

I watched the tower grow. Five years plans a new deal, wrapped in golden

chains, and I wonder, still I wonder, who'll stop the rain?

GROSS: Did you hear from people who were fighting in Vietnam that they played

your records there a lot and that your records mattered to them while they

were in the jungle?

Mr. FOGERTY: I would hear that off and on right around the time of 1970,

'71, but I heard about it a lot more later, as I began to become an adult and

guys who were now back and settled into the community would tell me all kind

of stories about Vietnam and the music that they experienced there.

GROSS: And what did that mean to you?

Mr. FOGERTY: Well, in some cases, it was very uplifting. I am proud that

these songs meant so much. You know, I realize, of course, that all the music

at the time meant so much, and especially to Americans off in a foreign land,

in a jungle, fighting for their life. I mean, anything--these are kids, these

are guys 20 and 21 years old--anything that is a touch of home is a very

welcome memory at that time.

GROSS: John Fogerty was the lead singer of Creedence Clearwater Revival. Our

interview was recorded in 1998. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Ray Manzarek discusses his career as keyboardist for

The Doors and his memoir, "Light My Fire"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We're going to conclude our series on

rock of the '60s with this 1998 interview with Ray Manzarek.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. JIM MORRISON: (Singing) Here I come. Yeah!

GROSS: That's The Doors, one of the great psychedelic bands of the '60s. The

mythology surrounding The Doors has mostly centered around its lead singer,

Jim Morrison, considered one of rock's tortured poets and sex gods. But

instrumentally, The Doors' distinctive sound was based on the keyboard playing

of Ray Manzarek. We invited Ray Manzarek to an interview at our piano, so he

could show us how he came up with some of his now classic organ solos.

Manzarek has written a memoir called "Light My Fire: My Life With The

Doors." The memoir focuses on the years the band performed together from

1965 through '71, the year of Jim Morrison's mysterious death.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. MORRISON: (Singing) When the music's over, when the music's over, yeah,

when the music's over, turn out the lights, turn out the lights, turn out the

light. Yeah. Yeah.

GROSS: Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison attended UCLA film school together,

but they didn't think of forming a band until they were both out of school.

Mr. RAY MANZAREK (Former Keyboardist, The Doors): Biblically, 40 days and 40

nights after we said our goodbyes after graduation, I'm sitting on the beach

wondering what I'm going to do with myself. Who comes walking down the beach

but James Douglas Morrison, looking great, lost 30 pounds, was down to

about one thirty-five, six feet tall, Leonardo--Michelangelo's "David." He

had the ringlets and the curly hair starting to kind of fall over his ears in

gentle locks. And I thought, `God, he looks just great.' And I said, `Jim,

Jim, come on over here, man. Come on. It's Ray. Hey, come on.' He said,

`Ray, oh, man. Good to see you.' And, you know, we did, `Hey, buddy,' `Hey,

pal,' you know, high-five and all that kind of stuff that guys do. And I

said, `Well, what have you been up to?' And he said, `Well, I decided to stay

here in Los Angeles.' I said, `Well, good, man, cool. Tell me, so what's

going on?' And he said, `Well, I've been living up on Dennis Jacobs' rooftop,

consuming a bit of LSD and writing songs.' And I said, `Whoa, writing songs.

OK, man, cool. Like, sing me a song,' you know, and he said, `Oh, I'm kind of

shy,' because I knew he was a poet. He knew I was a musician.

And I said, `Sing me a song.' So he sat down on the beach, dug his hands into

the sand and the sand started streaming out in little rivulets, and he kind of

closed his eyes and he began to sing in a Chet Baker haunted whisper kind of

voice. He began to sing "Moonlight Drive," and when I heard that first

stanza, `Let's swim to the moon, let's climb through the tide, penetrate the

evening that the city sweeps to hide,' I thought, `Ooh, spooky and cool, man.

I can do all kinds of stuff behind that. I could do kind of...'

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Sort of like, let's swim to the moon, you know. Let's climb

through the tide...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...penetrate the evening that the city sweeps to hide.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I thought, `Ooh, I can put all jazz chords and I can put

some kind of bluesy stuff.'

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: I thought, `Yeah.'

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I could do my Ray Charles, you know, and my Muddy Waters,

Otis Spann influences, and I could do just all kinds of bluesy, funky stuff

behind what Jim was singing. And I said, `Man, this is incredible. Let's get

a rock 'n' roll band together,' and he said, `That's exactly what I want to

do.' And I said, `All right, man. But one thing, what do we call the band?

It's got no name. We can't call it Morrison and Manzarek. I mean, you know,

M&M or, you know, Two Guys from Venice Beach or something.' He said, `No,

man, we're going to call it The Doors.' And I said, `The what? That's

ridiculous. The Door--oh, wait a minute. You mean like the doors of

perception, the doors in your mind.'

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And the lightbulb went on and I said, `That's it, The Doors of

Perception.' He said, `No, no, just The Doors.' I said, `Like Aldous

Huxley.' He said, `Yeah, but we're just The Doors,' and that was it. We were

The Doors.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's now the band got formed.

GROSS: So when you and Jim Morrison decided to create a band that left--the

lead singer and keyboard player, you still needed other musicians.

Mr. MANZAREK: Yep.

GROSS: So you ended up finding the drummer, John Densmore, and guitarist

Robby Krieger, but you became not only the keyboard player, but the bass

player, too. It was kind of...

Mr. MANZAREK: Well, it was of necessity.

GROSS: Tell us that story.

Mr. MANZAREK: We had the four of us. I found John and Robby in the

Maharishi's meditation...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and kind of an Eastern mysticism. We were into the same

kind of yoga The Beatles were into.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that came out of--the song "This Is The End" comes out

of that. So we were all seekers after spiritual enlightenment, and so was

Jim, of course. But we didn't have a bass player, so I applied my

boogie-woogie background, my rock 'n' roll boogie-woogie, because when I

discovered boogie-woogie...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...that was the whole thing. And you just keep that left hand

going. You don't do anything with it. It just goes and goes and goes and

goes.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And the right hand does the improvisations.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So I had done that over and over and over as a kid, so it was

very easy for me to--once we found the Fender Roades keyboard bass, 32

notes of extra-low sounding low notes, it was very easy for me to do...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So that's what I did on the piano bass.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Or like "Riders On The Storm"...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's what I did. I just over and over, repetitive bass

lines that are just like boogie-woogie, just keeps on going.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And it becomes hypnotic, and that's why lefty here is--thank

you--he did a very good job. He's not too quick.

GROSS: So y...

Mr. MANZAREK: He's a bit of a slow-witted fellow, lefty, but he's really

strong and solid and plays what he has to play, so lefty became our bass

player.

GROSS: So your left hand and right hand were playing separate keyboards.

Mr. MANZAREK: Oh, of course. Yeah. I had a Fender Keyboard Bass sitting on

top of a Vox Continental Organ, and the Vox Continental Organ was what I

played with my right hand and the Fender Keyboard Bass with my left hand.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. MORRISON: (Singing) Love me one time, could not speak, love me one time,

baby, yeah, my knees got weak. Love me two times, girl, last me all through

the week. Love me two times, I'm going away. Love me two times, babe. Love

me twice today. Love me two time, babe, because I'm a-going away. Love me

two time, girl, one for tomorrow, one just for today. Love me two time, I'm

going away. Love me two times, I'm going away. Love me two times, I'm blown

away.

GROSS: My guest is Ray Manzarek, who was the keyboard player for The Doors.

More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with Ray Manzarek, who was the

keyboard player for The Doors. Our interview was recorded in 1998 after the

publication of his memoir, "Light My Fire."

In your memoir, you write a lot, really, about how The Doors developed their

sound and how you developed your sound as the keyboard player with the group.

Let's take an example of one of those songs. Why don't we look at "Light My

Fire"...

Mr. MANZAREK: Sure.

GROSS: ...which is probably the most famous or one of the most famous...

Mr. MANZAREK: The most famous Doors' song. Yeah.

GROSS: Sure. Yeah.

Mr. MANZAREK: The most famous Doors' song. You know, Robby Krieger's

actually the writer of "Light My Fire." So Robby came in with a song. He

said, `I've got a new song called "Light My Fire."' He plays the song for us,

and it's kind of a Sonny and Cher kind of, `Dun, da, dun, da, dun, da, da, da,

da, dun, dah, light my fire.' And I was like, `OK, OK, good chords. You

know, what are the chord changes there?' and he shows me, an A-minor...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...to an F-sharp minor.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's like, whoa, that's hip.

(Soundbite Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: That's cool. And then...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's when he went into the Sonny and Cher part.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Da, da, da, da, da, da, da. And we said, `No, no, no, no, no,

no, we're not going to do this Sonny and Cher kind of song here, man.' And

that was popular at the time. Densmore says, `Look, we've got to do a Latin

kind of a beat here. Let's do something in kind of a Latin groove.'

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I'm doing this left-hand line. So John's doing

ka-ka-chooka-chooka doo-dah, you know. And we set up this Latin groove and

then go into a hard rock four...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And Robby's only got one verse. He needs a second verse, and

Morrison says, `OK, let me think about it for a second,' and Jim comes up with

the classic line, `And our love becomes a funeral pyre.' You know, `You know

that it would be untrue, you know that I would be a liar if I were to say to

you, "Girl, we couldn't get much higher"' is Robby's, and Jim comes, `The time

to hesitate is through.' In other words, seize the moment. Seize the

spiritual LSD moment. `The time to hesitate is through. No time to wallow

in the mire. Try now, we can only lose.' Whoa, that's kind of heavy. `Try

now, we can only lose,' meaning the worst thing that can happen to you is

death, `And our love becomes a funeral pyre.' Our love is consumed in the

fires of Ogney(ph). And it's like, `God, Jim, what a great verse, man.'

So we've got verse, chorus, verse, chorus, and then it's time for solo. So

anyway, the verse goes--John goes...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...eh, ah, doo, dah--you know how that goes. You've heard it a

million times.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And then into the chorus, `Come on, baby, light my fire.'

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So it's time then for some solos. We've done a verse, chorus,

verse, chorus. Now what do we do? We've got to play some solos. We've got

to stretch out. Here's where John Coltrane comes in. Here's where The Doors'

jazz background--John's a jazz drummer. I'm a jazz piano player. Robby's a

flamenco guitar player. And we all said, `You know, we're in A-minor. Let's

see, what do we do?' Da, da, da, da, da.

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: It ends up on an E, so how about...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: "My Favorite Things," John Coltrane. It's "My Favorite

Things," except Coltrane's doing it in D-minor...

(Soundbite of Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: But the left hand is exactly the same thing.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: It's in three, one, two, three, one, two, three, A-minor.

The Doors' "Light My Fire" is in four. We're going from A-minor to B-minor.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So it's the same thing as...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's how the solo comes about, and then we just go...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So it's John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things."

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And Coltrane's "Ole Coltrane" and then...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: That's the chord structure. Then I would solo over it.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Robby would solo over it, and at the end of our two solos, we'd

go into a...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...three against four...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and I'm keeping the left hand going exactly as it goes.

That hasn't changed. That's the four. On top of it is three.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And into the turnaround.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And we're back at verse one and verse two.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And we're back into our Latin groove, so it's basically a jazz

structure. It's verse, chorus, verse, chorus, state the theme, take a long

solo, come back to stating the theme again. And that's how "Light My Fire"

came about. The only thing left to do was to come up with that little

turnaround thing. I hadn't had that yet. And we said, `Now how do we start

the song? Do we just jump on an A-minor to an F-sharp? You know, are we

going to do that? Vamp a little bit?' I said, `No, no, no. We need

something more. We can't just vamp a little bit.' And I started--I put my

Bach back to work, put my Bach hat on and came up with a circle of fifths.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So I started like this...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Like a Bach thing, like...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So same kind of thing.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. B-flat, so I'm in G, D, F,

up to B-flat...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...E-flat...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...A-flat to the A to A-major, A-major. Yeah. That's it. And

then we'll go to the A-minor. I'm thinking all this to myself. So that's how

the introduction came about.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: F, B-flat, E-flat, A-flat, A...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and the drums and everything. Jim comes in singing.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And the Latinesque and then into hard rock. So that's how

"Light My Fire" goes. That's the creation of "Light My Fire."

GROSS: And you come up with this great organ solo in the middle...

Mr. MANZAREK: Oh, that was just luck.

GROSS: ...which is, of course, cut out of the single.

Mr. MANZAREK: Right, exactly.

GROSS: Because your producer figured, we've got to get this on the radio.

Mr. MANZAREK: Right.

GROSS: So we've got to do a singles version...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah. We had to cut down six...

GROSS: ...and it was--What?--six or seven-minute track.

Mr. MANZAREK: ...seven minutes--we had to cut down seven minutes to two

minutes and--under three minutes, you know, two minutes and 45 seconds, 2:50

would be ideal.

GROSS: So he calls you into the office, plays you his version...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah. Well...

GROSS: ...his edited version.

Mr. MANZAREK: ...Paul Rothchild, a brilliant genius, producer, and Bruce

Botnick was our engineer. Those two guys were--those were Door number five,

Door number six. Without those two guys--there were six Doors in the

recording studio, the four musicians and Paul Rothchild and Bruce Botnick.

Without them, we never would have done nearly what we did. Paul said, `I'm

going to make an edit here. I'm going to do some edits. I'm going to cut

"Light My Fire" down from seven minutes to 2:45, 2:50,' and I said, `Good

luck, man. I don't see how you're going to do it.' Two days later, Rothchild

calls and said, `OK, man, I got it.' I said, `You got it? How did you do it

so fast? You've got a thousand cuts.' And he said, `No, no, no. Just come

on in. I'm not going to tell you what I did, how I did it. I just want you

to listen to it.'

So the song starts. We're all in the control room on the big speakers at

Sunset Sound. The song starts...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: We're at the regular introduction and then it's into...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and it's going along and then `Come on, baby, light my

fire.' And that's going along. Now we're into the second verse. `The time

to hesitate is through, no time to wallow in the mire. Try now, we can only

lose. Our love becomes a funeral pyre.' Everything's going exactly--`Come

on, baby, light my fire.' Nothing has changed. Everything is exactly the

same. `Come on, baby, light my fire. Try to set the night on fire.' Now

it's time for the solos. I think, `Where's the edit, man?' And we're into

the solos.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I thought, `I don't know where he's going to cut. This is

insane.' And all of a sudden, where I'm supposed to go...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...you know, play my organ solo, what happens, it goes...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: It goes to the end of the solos...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and then back into the turnaround, and there's like not a

solo. There's no solos where--I'm out. I've got three minutes of solo.

Robby's got two and a half minutes of solo. It's all gone. It just goes,

dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, and turnaround...

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I think, `Oh, no, what's'--and then we go back into verse

number three.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And then we do that exactly as the song is, and then verse

number four. `It's time to hesitate, no time to wallow in the mire. Our

love becomes a funeral pyre. Come on, baby, light my fire. Come on, baby,

light my fire. Try to set the night on fire, try to set the night on fire,

try to set the night on fire.' And it's the end of the song, and that's it.

It's two minutes and 45 seconds long, and there are no solos in the entire

song, and I thought, `I'm going to kill this guy.' Or I looked at Robby and

Robby said, `You want to kill him? Let's kill him.' And Paul said, `Hold it,

hold it. Listen, I know the solos aren't there, but just think. You don't

know the song. You've never heard the song. You're 17 years old. You're in

Poughkeepsie, you're in Des Moines, you're in Missoula, Montana, you've never

heard of The Doors. All you know is a two minute and 45 second song is going

to come on the radio. It's called "Light My Fire." Does that work?' And we

all looked at each other and said, `You know what, man? You're right. It

does. It works.'

(Soundbite of "Light My Fire")

THE DOORS: (Singing) You know that it would be untrue, you know that I would

be a liar if I was to say to you, `Girl, we couldn't get much higher.' Come

on, baby, light my fire. Come on, baby, light...

GROSS: My guest is Ray Manzarek, who was the keyboard player for The Doors.

More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

THE DOORS: (Singing) Oh, show me the way to the next whiskey bar. Oh, don't

ask why. Oh, don't ask why. Show me the way to the next whiskey bar. Oh,

don't ask why. Oh, don't ask why. For if we don't find the next whiskey bar,

I tell you we must die, I tell you we must die, I tell you, I tell you, I tell

you we must die. Oh, mou...

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with Ray Manzarek. He was the

keyboard player for The Doors. Our interview was recorded in 1998 after the

publication of his memoir, "Light My Fire."

One of the really big stories and the lure of The Doors is the concert in

Miami...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yes, it is.

GROSS: ...where many people say that Jim Morrison exposed himself and...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yes, they do.

GROSS: ...you say he didn't exactly. But he had seen The Living Theater a

few days before, and that was like the theater group who was experimenting

with, you know, breaking down the fourth wall and taking off their clothes in

the middle of theater performances, confronting the audience and so on, and he

was influenced by that.

(Manzarek plays piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Yes, he was.

GROSS: So...

Mr. MANZAREK: Go ahead.

GROSS: Well, what did he say to the audience that got the audience so excited

and so expecting him to expose himself?

Mr. MANZAREK: Well, what he said, I don't know if I can say that on the radio

here. My goodness.

GROSS: Well, we'll do the clean version of what he said.

Mr. MANZAREK: OK, it's the C-word. He said the C-word, ladies and

gentlemen. We won't go any further than that. We're in Miami. It's hot and

sweaty. It's a Tennessee Williams night. It's a swamp and it's a yuck, a

horrible kind of place, a seaplane hanger, and 14,000 people are packed in

there, and they're sweaty and Jim has seen The Living Theater, and he's going

to do his version of The Living Theater in front of--this is the first time

he's been home. He was born in Melbourne, Florida. This is virtually his

hometown, and he's going to show these Florida people what psychedelic West

Coast shamanism and confrontation is all about.

He takes his shirt off in the middle of the set and says, `You know, you

people haven't come to hear a rock 'n' roll'--he's drunk as a skunk and he

didn't tell any of us what he was going to do. If only he'd have told

somebody. He said, `You didn't come to hear a rock 'n' roll band play some

pretty good songs. You came to see something, didn't you?' And they're all

going (makes noise). He said, `What'd you come to see? You came to see

something that you've never seen before, something greater than you've ever

seen. What do you want? What can I do for you?' And the audience is going

like this, you know. I'm playing the piano right now inside the strings.

That's how the audience--it's just rumbling and rumbling. And he said, `OK,

how about if I show you my C-word?' and all the audience goes screaming crazy.

It was like madness.

And Jim takes his shirt off, holds it in front of him, reaches behind it and

starts fiddling around down there, and you wonder, `What is he doing?' And I'm

thinking, `Oh, God, he's going to take it off' and the audience is getting

crazier and crazier. And then Jim whips the shirt out to the side and he

said, `Did you see it? Did you see it? Look, I just showed it to you.

Watch, I'm going to show you my C-word again. I'm going to show it to you.

Now keep your eyes on it, folks,' and he whips it out. Oh, off to the side

again, off to the side again, off to the side and says, `I showed it to you.

You saw it, didn't you? You saw it and you loved it and you people loved

seeing it. Isn't that what you wanted to see?' And sure enough, it's what

they wanted to see. They hallucinated. I swear the guy never did it. He

never whipped it out. It was like on the West Coast, Jesus on a tortilla. It

was one of those mass hallucinations. It was--I don't want to say the vision

of Lourdes because only Bernadette saw that, but the other people believed,

and maybe other people saw it. It was one of those kind of religious

hallucinations; except it was Dionysis bringing forth, calling forth snakes.

GROSS: And then you say he said to the audience, `Come closer, come on down

here.'

Mr. MANZAREK: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. Come on down.

GROSS: `Get with us, man.'

Mr. MANZAREK: Sure. `Come on, join us. Join us onstage.' Sure. And they

started coming on a rickety little stage, and the entire stage collapsed.

Sure.

GROSS: Toward the end of The Doors' life as a band, Jim Morrison could only

play like three nights in a row, and he'd just be kind of either spent or just

too--What?--too depressed or manic to--one or the other--to play after that?

Mr. MANZAREK: No. It wasn't too manic. No, the manic side--no, it was his

energy was giving out.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MANZAREK: He was depleting his energy with alcohol, and physically, on

the first night, he was fine. The second night, he was halfway drinking too

much, and by the third night, the booze would catch up with him and he was

just kind of hanging on to the microphone, and he had lost his chi is what he

had lost.

GROSS: When he went to Paris for what you thought would be some rest and

relaxation, he ended up dying there...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah.

GROSS: ...mysteriously...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yes.

GROSS: ...at the age of 27.

Mr. MANZAREK: Yes.

GROSS: So did you have to reinvent yourself after Jim Morrison died and that

was the end of The Doors?

Mr. MANZAREK: No. I just had to get on to the next thing. I was the same

person I was before. You know, my psychedelic and cosmic vision formed when I

was 25 is the exact same one I have today. What I'm telling you today is what

I would have told you two weeks after Jim Morrison died. I'm the exact same

person. You know, once you open the doors of perception, you know, `Ray, do

you still take acid?' No, I don't take acid. `Do you still get high

anymore?' You don't need to. Once you open the doors of perception, the

doors of perception are cleansed. They stay cleansed. They stay open, and

you see life as an infinite voyage of joy and adventure and strangeness and

darkness and wildness and craziness and softness and beauty. So that's how I

live my life and I haven't changed. I didn't really have to reinvent myself.

It took a long time to get over Jim's death, however, you know. That was a

sad, sad period for me.

GROSS: Ray Manzarek, recorded in 1998, after the publication of his memoir,

"Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors." We hope you enjoyed our series on

pop and rock of the '60s.

THE DOORS: (Singing) People are strange when you're a stranger, faces look

ugly when you're alone. Women...

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

THE DOORS: (Singing) ...no one remembers your name when you're strange, when

you're strange, when you're strange. People are strange when you're a

stranger, faces look ugly when you're alone. Women seem wicked when you're

unwanted. Streets are uneven when you're down.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.