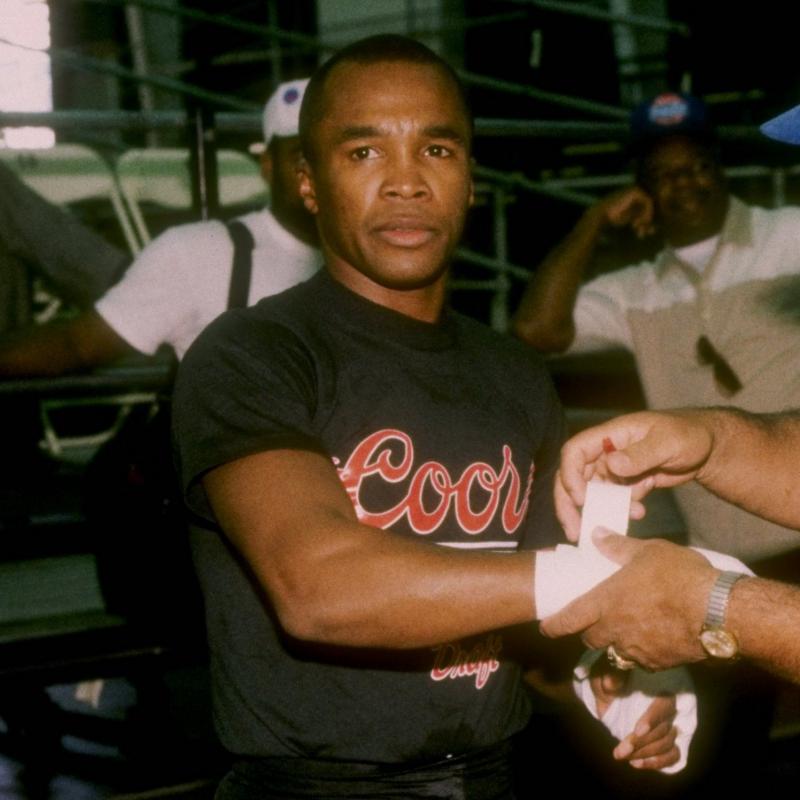

"On the Ropes" with Harry Keitt.

Boxing trainer Harry Keitt. He can be seen in the new documentary "On the Ropes" about the world of boxing at a Brooklyn neighborhood gym. Filmmakers Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen follow four boxers and Harry Keitt, their trainer, as they prepare for the 1997 Golden Gloves Tournament.

Other segments from the episode on September 7, 1999

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: SEPTEMBER 07, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 090701np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: "On The Ropes": An Interview with Boxing Trainer Harry Keitt

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: From WHYY in Philadelphia, I'm Terry Gross with FRESH AIR.

"On the Ropes" is a new documentary about a boxing center in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. The film follows three young boxers and their trainer, Harry Keitt. On today's FRESH AIR, we talk with Keitt about his own boxing career, his years in prison, and how he became a trainer determined to stop young people from making some of the mistakes he did.

And we talk with singer and actor Kris Kristofferson. His new CD features new versions of his best known songs, including "Me And Bobby McGee" and "Help Me Make it Through the Night." Also linguist Geoff Nunberg considers how youth slang is now constantly appropriated by the advertising and marketing worlds.

That's all coming up FRESH AIR.

First the news.

(NEWS BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP - "On the Ropes")

HARRY KEITT, BOXING TRAINER: I've basically been at the gym for, like, 16 years, 16 years as a fighter, now as a trainer. Any other gym is like a business venture. (INAUDIBLE) our gym is more like a family, you know what I'm saying? At times, you know, I get -- I get fed up. I say I'm going to leave this gym. See, it's hard to leave this gym. We don't have a lot of equipment. We don't have a lot of glamor. (INAUDIBLE) came from no heat to some heat, from no light to some light, the pocket missing off the pants. Sometimes the guy that don't have it, he's hungry because he's trying to get it.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: That was my guest, Harry Keitt, speaking about the work he does as a boxing trainer at the Bed-Stuy Boxing Center in Brooklyn. What we heard is an excerpt from the new documentary "On the Ropes." The film was made by Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen. Burstein trained at the Bed-Stuy Boxing Center before deciding to make the movie.

The film follows Keitt and three of his young boxers from 1996 to '98. Two of them, Tyrene Manson (ph) and Noel Santiago (ph), are shown preparing for the 1997 Golden Gloves tournament. The third, George Walton (ph), won the tournament in 1996.

Here's Keitt ringside coaching Santiago.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP - "On the Ropes")

KEITT: What's our slogan?

NOEL SANTIAGO, BOXER: (INAUDIBLE) do or die.

KEITT: What's our slogan?

SANTIAGO: (INAUDIBLE) do or die.

(CROSSTALK)

KEITT: That's right. (INAUDIBLE) go out there and fight like you never fought before. Fight like you fighting Mike Tyson. Fight like you fighting me in the ring.

UNIDENTIFIED VOICE: Even if the (INAUDIBLE)

KEITT: (INAUDIBLE) back, you know what I'm saying? You know my -- you know my specialty. Mighty (ph) shots.

(CROSSTALK)

KEITT: Who the man?

SANTIAGO: (INAUDIBLE)

KEITT: Who the man, Noel?

SANTIAGO: (INAUDIBLE)

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: What did boxing mean to you when you were young and first started training?

KEITT: It meant everything to me back then because, you know, because I've tried, like, basketball, football and stuff like that, and it didn't work out for me. And so when I got -- when I got into boxing, like, you know, I fell in love with the sport, you know what I'm saying, because, you know, I was the center of attention, and it wasn't a whole team, and it wasn't nothing like that. It was all about me. And so, like, you know, the boxing (INAUDIBLE) almost, like, you know, (INAUDIBLE), like, be a parent to that kid because you get -- you get the attention that you -- sometime you don't get at home. You get that personal attention. You get that loving care, and you get all of that.

GROSS: Let's talk a little bit more about what boxing means to you. I know you had started a pro career in about 1980, and you worked for several months as Muhammad Ali's sparring partner. But then your career got -- well, your professional boxing career basically ended when you were convicted on drug charges and attempted murder. I think you served four years in Sing-Sing and Attica.

What -- you shot your cousin seven times? What happened? What was that about?

KEITT: Oh, you know, that was -- that was one of them -- one of the down parts of my life, and I was -- you know, I was selling drugs, and he -- he had robbed the place and -- and I just -- you know, I just got stupid, you know what I'm saying? And I done a bad thing, and I did that. At the time, you know, I didn't think like that. At the time, I thought, you know, I was a man and I was the king of the street and stuff like that. And so when I -- when I -- when I did that, you know, it didn't -- it didn't hit me until after the fact. It didn't hit me till I was laying up in -- when I was an 8-by-4, laying in that prison cell and thinking, and all the thoughts started coming to me. I started having nightmares and stuff like that. And that's when I know I made a bad mistake. I made a terrible mistake.

GROSS: And when you got out of prison after serving your four years, I think you were homeless for a while.

KEITT: Yeah. You know, I got caught up in the drug game, and I started -- from -- from selling drugs, I started using drugs. And one thing led to another, and I, you know, became homeless on the street, not washing, eating out of the garbage can and -- you know, and I -- I just walked around the street just, like, aimlessly for, like -- like, three to four years and, you know, not -- you know, I was directionless. Ain't have no sense of purpose, no sense of being -- you know, just -- I was just out there and -- and it took me a while, you know. Took me a while to go into a drug program to get my life back in order. And so when I did that, once I got out of -- after I completed the drug program, and I told myself that a drug program was hard, and I said once I get out of this, if I -- once I graduated from the drug program, and I promised myself and I promised God I would never, ever use drugs again a day in my life.

GROSS: How did you figure out that what you really wanted to do was train young boxers?

KEITT: Oh, like, when I -- my first young fighter -- because I was training -- I made an attempt to make a comeback and...

GROSS: Oh, really? After you started boxing again?

KEITT: Yeah, I started -- I made an attempt to make a comeback. When I came back to the gym, like, after -- after the drug program, I started training again. And then I got with this guy, right, and he -- and I signed a contract to fight for him. But it was, like, you know -- you know, it takes -- when you out of the game for a long time, it takes a good while for you to get your body and mind back in shape.

And so, like, after six months -- and I was, like -- out for, like, four years -- he wanted me to fight, and I felt I wasn't ready. So he kept bugging me and bugging, bugging me, so I -- I said, "Man, listen, forget about it. I'm not fighting." So I took on the first kid.

I started training him, a kid by the name of Eric Kelly (ph). And I started training him, and he was -- he became, like -- he was, like, my first champion, and he was a -- he was a young kid, junior (INAUDIBLE) champion. I started training him. And then I started liking it because, you know, now I was on the other side of the fence. You know, now I was on the other side of the fence. And then being on that side of the fence felt good, you know? Now I felt like I really meant something, not just a boxer that's getting in the ring and stuff like that.

Now I really -- I had a purpose for being. And so when I got into -- you know, when I started training fighters, that made me feel good about myself, and that gave me more of a reason not to go back to drugs again because now I say, "Now this is what I want to do. This is -- this is going to be my job."

GROSS: Now, you said when you were younger, you really thought of yourself as, you know, king of the street, and that that ended up getting you into a lot of trouble. Are there certain attitudes that you try to change in the young boxers who you're trying to mold?

KEITT: Yeah, because sometime you have to -- you -- you -- sometime you get a fighter, you come in -- they come in the gym -- they come in the gym cocky. They come in the gym in a bad attitude. Some of them come in the gym, you know, with a lot of confidence. Some (INAUDIBLE) come in the gym with no confidence. And what you want to first get a person to believe in themselves, you know what I'm saying?

A lot of -- and boxing is a sport where the majority of people that come to box doesn't believe in theyself, you know? They got a self-esteem problem. And what you want to do, you want to build on that. You want to try to build them up, and that's what we work on that. Now, we try to not just -- we just not there just to teach a person to be a good fighter because it's not about being a good fighter. It's about being a good human being.

GROSS: Now, at the beginning of the film, you're working with a young boxer named Noel Santiago. He's a welterweight who seems very promising, but lacks self-confidence, and I think also probably lacks a little bit of discipline. And you say to him early in the film, you say, "For the next couple of weeks, put your life in my hands."

What did you want him to do by putting his life in your hands for that couple of weeks?

KEITT: I mean it -- I mean it -- "Just relax. Trust me," you know what I'm saying? "Until you learn to -- until you learn to believe in yourself, believe in my for a minute. And if you can believe in me, then you can start -- in turn start to believe in yourself." And that's what the message I was trying to get across to him. If you can believe in anybody -- because most people that doesn't have self-esteem doesn't believe in anything, you know what I'm saying?

And in most -- most -- the majority believe in the wrong -- in the wrong thing, in the wrong people. They believe in the next-door drug dealer who's driving a Lexus or who's driving their brand-new car of that year, you know what I'm saying? They believe in those kind of people, and those kind of people is not going nowhere fast. And so -- and if I can just get him to believe in anything, you know what I'm saying, believe in something greater than the street, you know, and -- or believe in -- get to just believe in me just for a moment, and say believe that I can help you.

GROSS: Obviously, you want your boxers to win, but they're not always going to win. What do you try to teach your boxers about losing and how to handle losing?

KEITT: What I tell them, right, is -- what I tell them -- I tell them -- I tell a fighter like this. "Train hard. Train very hard. If you lose, you know what I'm saying, lose because the guy was better than you that day. Don't lose because you short-changed yourself by not doing all that you can do, not doing all the necessary running that it takes, not doing all the push-ups that it takes, not doing everything that you know you should have done to try to win." And that's what I try to get over -- get across to them. "And if you get beat, get beat because the guy was better than you, and don't get beat for no other reason."

GROSS: The most successful of your boxers in the movie "On the Ropes" is George Walton, who won the Golden Gloves and also won the Empire State Games and was in the Eastern -- I think was a finalist in the Eastern Olympic trials? Is that right?

KEITT: Eastern region.

GROSS: Eastern region.

KEITT: Eastern region of the Olympic trials, yeah.

GROSS: Now, he started fighting professionally while the film was being made, and in the film, you warn him that a lot of the people who manage professional boxers exploit them. What were your fears about what would happen to him?

KEITT: Because George (INAUDIBLE) When you got a fighter, right, and they first come to the gym, people doesn't pay attention to them. They wait for a while. They see what -- see what -- how you're going to mold them, what they're going to look like. Then when they saw (INAUDIBLE) looking real good and promising, then everybody have advice for them. And I -- and we -- and I talk to my fighters about that, and I talked to George about that. They know when "(INAUDIBLE) right now, nobody ain't paying attention to you, but when you get real good, everybody going to -- everybody going to have some advice for you. And all of a sudden, the person who's training you doesn't know a thing." And they got to him, and they told him that, you know, I didn't know much and -- and he didn't know that, and he didn't realize that. He only got to where he got because of what I taught him. And so one thing led to another. The guys came around with the money, with the suits, dining him, taking him to different places. And one thing led to another, he was gone.

GROSS: How did you feel about him breaking his relationship with you?

KEITT: I mean, it wasn't -- it wasn't a good feeling at all, you know? When you've been -- when you've been with a person, you've been part of their life for so long, and they done told you all kind of different things, and now one thing led to another, and -- and you break apart because of some outside interference that don't really have nothing to do with you, you know, it's a hurting feeling. But I mean, what can you do? You just got to move on and keep going.

GROSS: You know, in the film, the documentary, you say that you didn't want to be cut out, but if his management did cut you out, you wanted his managers to buy you out. In some ways, I felt you were kind of putting this young boxer on the spot by encouraging him to stick with you when he was by other people being encouraged to go with people who had more experience handling professional boxers.

KEITT: No, I wasn't really putting him on the spot because it's like this. If you're going to go to a doctor, right, you're not going to go to a bicycle (ph) specialist to get your heart surgery. You're going to go to somebody -- you're going to go to somebody who know what they're doing. You're going to go to a specialist. You understand what I'm saying?

GROSS: Uh-huh.

KEITT: And people that was trying to manage him didn't know a thing about boxing. They was in the music industry, you know, and music and boxing, they're both in the entertainment business, but it's different kind of entertainment. And music and boxing is two different things, and if you don't know what you're doing, all you're going to do is screw up.

GROSS: Well, during the movie, we see this young boxer, George Walton, ended up -- ending up feeling like he's being exploited by his new management. He was getting a salary, but they were keeping the purses, and he didn't feel like he was getting a share take (ph) of the money for his wins.

What was the outcome? What's George Walton doing now?

KEITT: Right now he's living in Florida, Orlando, Florida. He continue fighting. He is not with the people that was managing him anymore. They released him. So now he fought, like, maybe, like, a month ago, or a month and a half ago in Florida. Now he's his record went from 4 and 0, he's 5 and 0. I don't know when he's fighting again, but I know he'll probably be fighting again soon.

GROSS: Now, Tyrene Manson, a woman who you're shown training in "On the Ropes," was about to fight in the Golden Gloves tournament when she was convicted on charges of selling crack. She maintained her innocence through the trial. And she I believe is still in prison?

KEITT: Yes. Yes, she is.

GROSS: She's serving how long of a sentence?

KEITT: They gave her four and a half years to nine. And she -- maybe she should -- maybe -- she may be released on early work release in October.

GROSS: I don't want to put you on the spot here, but do you believe that she was innocent?

KEITT: Sure, I did. And I think the only reason why she went to prison is if she would have (ph) never took the witness stand because they didn't really have nothing on her, you know what I'm saying, because she didn't do nothing. I knew Tyrene. I knew the woman. I knew her very well. And I knew her situation at home. I knew her conditions of her living and everything else. And she was just trying to make all ends meet.

GROSS: What kind of advice did you give her during her trial, when she really wanted her mind to be in the ring, because she was training for the Golden Gloves, and yet she was facing this really important court battle? What did you tell her?

KEITT: I tell her "Just stay calm and just relax and just believe in God and believe in yourself." And you know -- and when -- Tyrene was so angry and so upset, she wanted to fight. And when they did put her on the witness stand, she lost it, you know what I'm saying, because she was angry. She wanted to fight. So if you look at her in the trial on the witness stand, she was fighting with the DA. Then she had her fight. See, she couldn't fight -- since they wouldn't let her go fight in the ring, she took all her anger out on the DA, on the district attorney, and that's where she lost it at on the stand, by being angry, not because she was guilty.

GROSS: And some of that is actually shown in the film, "On the Ropes." Is Tyrene Manson still training while she's in prison?

KEITT: Yes, every day. I mean, every single day she trains, you know? Every day, I think she does so many thousand of push-ups. Because I went to visit her, and her stomach is, like, hard as a rock, or like trying to bend a wall, you know? So (INAUDIBLE) there, walking around 112 pounds. I mean, put on some -- eat fast and gain some weight because when Tyrene get out, you all going to have to watch out.

GROSS: My guest, Harry Keitt, is a boxing trainer at the Bed-Stuy Boxing Center in Brooklyn. He's at the center of the new documentary "On the Ropes."

We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(ID BREAK)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Harry Keitt. He's a trainer at the Bedford-Stuyvesant Boxing Center, and he's the central figure in the new documentary "On the Ropes." The film follows him and three of his boxers as the boxers prepare for the 1997 Golden Gloves tournament.

Who trained you?

KEITT: A man by the name of George Washington.

GROSS: And what did -- did you like him a lot?

KEITT: Oh, George was like a father, and he was like the father I never had because because, you know, I never -- when I was a kid, I never saw my father. So George was -- he made me feel like I could knock the world down. He made me feel like I could go up against the army by myself.

And when George was in my corner -- I mean, George got this kind of voice that he know he -- I mean, even if I -- say I got beat the first round, in the second round I came out and sometime I just knocked the guy out because he made me feel like I can just -- I can just knock out King Kong. He's -- I mean, because he got this gravel-type voice, say "Come on, Harry. You can knock this kid out. You know, just walk him -- just walk to him, stalk him and walk him down." And 9 times out of 10, I did that.

GROSS: What did you have the most trouble with when you were fighting?

KEITT: Myself. Myself hanging out and -- we were doing drugs, smoking weed and stuff like that. I mean, like, all the stuff that I ask of my kids, you know what I'm saying, I didn't do when I was a fighter. And so -- and that's why I ask so much of the kids that I'm training because a lot of stuff I know I lacked, and a lot of stuff I didn't do it when I was a fighter. So now I ask -- I ask more of them than I asked of myself at the time when I was a fighter.

GROSS: Could your trainer tell when you were doing drugs?

KEITT: Sure, he knew. He knew. But see, he knew certain things I did. From being a fighter or from being anything, you know when a person is doing whatever, you know what I mean? I can tell when a person is not running. I can tell when a person basically almost having sex or anything because I can tell by their layers (ph). I can tell how they're breathing. You know, I can tell anybody anything what they're doing and what they're not doing.

GROSS: Now, I understand you don't get paid for your work as a trainer?

KEITT: No. I would like to, but you know, at the gym, we -- at the gym I just happen to work at is a non-profit organization, you know what I'm saying? We don't get no kind of profit. We don't have -- we don't get nothing from nobody. And the only (INAUDIBLE) we don't get nothing from nobody, and the reason why we're able to work because we have dedicated trainers that put their time and their efforts into the gym and into the kids and we don't get -- and so, like, sometime we -- when you do -- when you do bring up somebody that's great or that's good, you know what I'm saying, I think -- not that I think -- I mean, you do want to go along with that person. You want to be with that person and...

GROSS: You want to share in their success...

KEITT: Well, sure. Sure.

GROSS: ... both the glory of it and the money of it.

KEITT: Because you shared in the -- you shared in it -- you shared in bringing him up, you know? You brought him up from no -- from nothing, you know what I'm saying? So you just have -- you should have the right to go to the rest of the way with that person.

GROSS: So how do you make a living, if you're not getting paid for the boxing?

KEITT: Oh, right now I work at this -- I work at a club in Manhattan. I'm a bouncer, you know? I'm looking to get another job soon doing construction work, but right now I'm a bouncer working three days a week. And I do -- and I'm at the gym -- and I'm at the gym six days a week, you know? And some day, I be so tired, but I'm saying but I -- no, because I know when George was doing it, George was -- because at the time when I was a fighter, George -- I was to be the last fight because I was -- I was a heavyweight. And George wouldn't get home till, like, 2:00 o'clock in the morning out of Madison Square Garden, and he had to be to work 6:00 o'clock in the morning in New Jersey. And so -- so you know, that's why -- that's where I get my strength from.

GROSS: What kind of music is it at the club?

KEITT: They play '80s music in Manhattan. You play music from the '80s. But it's crowded all the time and stuff like that. It's a great club, you know. But for me, as a person, I just -- because I don't like -- you know, I like to work -- I'm an early morning guy, and I can't sleep in the daytime, and I'm an early morning guy. I like to, you know, get up, like, 5:00 or 6:00 o'clock in the morning. Those are my hours because, you know, as a fighter, I used to get up, like, 4:30, 5:00 o'clock in the morning to go do road work, because I'm an early morning person. I'm not a kind of person that lay in bed all day. I don't like laying in bed, so I like to get up early in the morning, do what I got to do, and that's it.

GROSS: What's the greatest success any of your boxers have gone on to?

KEITT: Oh, I have a fighter right now, and he's 16 years old. He's number one in the world, a fighter by the name of Mark Ineen (ph). He's number one in the world right now.

GROSS: Number one among...

KEITT: The juniors. He's 16 years old. This is his last year as a junior. He won the junior -- he won the JO (ph) nationals in Marquette (ph), Michigan, and he won the junior worlds in Mexico. So right now he's rated number one in the world.

GROSS: And what are you hoping for him?

KEITT: It's -- like, he's one of -- he's one of my -- one of the kids that I don't have no problem on. He gets up and runs. I mean, he does it all, you know? I tell him what to do, he just go out there and do it, and he tries his best because he like the feeling of winning. He like the feeling of being -- raising his hands in the ring. And believe me, he's -- when he came in the gym, he was a fat little pudgy kid...

GROSS: (laughs)

KEITT: ... and he was an un -- he was an un-adult kid that then rose to the top, you know, and now he get great respect. He's one of them kids. He got a 80 average in his school, and he works hard for what he wants, and he knows exactly what he wants. And he's one of them kids, he got his -- he got a good head on his shoulder. He's not in the street. I mean, he -- a kid like that, you would want him for a son.

GROSS: Harry Keitt, thank you very much for talking with us.

KEITT: Thank you.

GROSS: And good luck to you.

KEITT: All right.

GROSS: Harry Keitt is a trainer at the Bed-Stuy Boxing Center. He's featured in the new documentary, "On the Ropes," directed by Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Harry Keitt

High: Boxing trainer Harry Keitt can be seen in the new documentary "On the Ropes" about the world of boxing at a Brooklyn neighborhood gym. Harry discusses the movie and his boxing and training career.

Spec: Sports; Entertainment; Harry Keitt

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: "On The Ropes": An Interview with Boxing Trainer Harry Keitt

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: SEPTEMBER 07, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 090702NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: An Interview with Kris Kristofferson

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:30

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Songwriter, singer, and actor Kris Kristofferson has a new CD in which he does new versions of his best-known songs, songs like "Me and Bobby McGee," "For the Good Times," and "Help Me Make It Through the Night."

Kristofferson first came to Nashville in the '60s after being a Rhodes scholar and serving in the military. His first job in the music industry was working as a janitor at Columbia Records, where he met Johnny Cash, who became his good friend, recorded Kristofferson's songs, and convinced Kristofferson to start recording himself.

Kristofferson is well known for his acting as well as his singing. Recently he appeared in the John Sayles films "Lone Star" and "Limbo," as well as "Payback" and "A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries."

Right now, he's getting back to normal after having triple bypass heart surgery three months ago.

Let's get started with his new version of perhaps his best-known song, "Me and Bobby McGee."

(AUDIO CLIP: EXCERPT, "ME AND BOBBY McGEE," KRIS KRISTOFFERSON)

GROSS: Kris Kristofferson, welcome to FRESH AIR.

KRIS KRISTOFFERSON: Thanks, Terry.

GROSS: Let me ask you a little bit about the song that we just heard, "Me and Bobby McGee." What first inspired that song?

KRISTOFFERSON: Fred Foster, who owned Monument Records and Combine, called me up, said he had a song title for me that was "Me and Bobby McKee." I thought he said "McGee," but actually he -- there was a girl named Bobbie McKee who was Boodle O'Bryant's (ph) secretary, and they were in the same building, (INAUDIBLE)...

GROSS: Boodle O'Bryant wrote a lot of songs for the Everly Brothers.

KRISTOFFERSON: Yes, he did, you're right on it. And anyway, he said, "The hook is, Bobbie McKee is a she," you know. And I thought that sounded like the worst idea I'd ever heard of. (laughs)

But I wanted to write for -- write something for him. I had not had anything recorded since I'd gone to work for his company, and so I set out to write the song. And hid from him for a few months, and went back in and into our studio up there at Combine with Billy Swann (ph) and made a demo of it. And everybody liked the song.

GROSS: (laughs) The most famous line from the song is, "Freedom's just another word for nothing left to lose." What inspired that line?

KRISTOFFERSON: Well, that's what the song was really about to me, was the double-edged sword, you know, that freedom is. And when I wrote that, some of my songwriter friends in Nashville told me to take it out of the song, said it was -- that it didn't fit, that the rest of the imagery was so real and concrete that it was out of place to put a little philosophical line in there.

GROSS: Tell me if I remember correctly. Did you have a house that burned down at about the time you wrote this song?

KRISTOFFERSON: No, no, I had had -- I tell you what I had. I was living in a condemned building at the time, and in a -- you know, thing that cost me, I think, $50 a month. And somebody had broken into it during the week that I was down in the Gulf of Mexico, and trashed the place and stole what little I had to steal.

I remember it was a very liberating feeling to me, because everything was gone. And there was no where to go but up. I had also alienated my family at the time, my wife had left me, and I was separated, you know, from my kids. And I think I'd been disowned by my parents by that time.

And it was pretty liberating, not having any expectations or anything to live up to.

GROSS: How did Janis Joplin end up recording this song?

KRISTOFFERSON: Bobby Neuwirth (ph) taught Janis the song, I believe, and I think he'd heard it when Roger Miller had recorded it. I first heard that she had sung the song when I came back from -- I'd been down in Peru making a movie with Dennis Hopper, singing "Bobby McGee," as a matter of fact, in the film.

And somebody told me she had sung it in a concert, I think it was in Nashville. And then later Bobby introduced me to her. We lived out at her house for about a month or so. And we became close friends, but I never did hear her sing it. I never heard her tape of it till the day after she died. Paul Rothschild played it for me.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Kris Kristofferson, songwriter, singer, and actor.

What year did you first get to Nashville, and what was it like when you got there?

KRISTOFFERSON: I first went there in June of 1965, and was on my way back from a three-year tour in the Army in Germany, and was on my way to the career course down in Fort Benning, and from there to -- supposedly to teach English at -- literature at West Point.

And since my military obligation was already fulfilled, I decided I was going to get out of the Army and be a songwriter. I had spent a couple weeks there just on tour -- I mean, just -- you know, I was on leave and got shown around to some of the songwriters' sessions and got a glimpse of the life.

I've always felt like I was really lucky to have been exposed to Nashville at that time, because I'm sure it's different now.

GROSS: There must have been some kind of life-changing thought that happened to you, since you'd been on this military career track. Your father had been a military career man. Was it a sudden change of heart, or what, that made you think, I'm not going to teach at West Point, I'm going to try writing songs in Nashville?

KRISTOFFERSON: Well, I had never intended to make the military a career, or academic life. I always thought that I would -- I hoped that I would be a writer and be able to have a creative life, you know. And then -- well, when -- after I graduated from college, I went to Oxford for a couple of years, and then I went in the military for almost five years.

And by that time I had a family, and, you know, wife and a daughter, and I think I sort of despaired of ever making my living as an artist, until I went to Nashville. I went there because in my last year in the Army over in Germany, I'd formed a band and started writing songs again. I'd been writing songs all my life, but started really escaping into it during the last year I was over there in Germany.

And went to Nashville to try to peddle the songs. And then when I got there, it was so different from any life that I'd been in before, just hanging out with these people who stayed up for three or four days at a time, you know, and nights, and were writing songs all the time. I think I wrote four songs during the first week I was there.

And it was just so exciting to me, it was like a lifeboat, you know, it was like my salvation.

GROSS: My guest is songwriter, singer, and actor Kris Kristofferson. His new CD is called "The Austin Sessions." We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Kris Kristofferson is my guest, songwriter, singer, and actor. He has a new CD on which he does new versions of some of his best-known older songs, and it's called "The Austin Sessions."

How did you start making movies? Did you think one day, I'm going to act?

KRISTOFFERSON: When I started performing my own songs in my first -- the first place I ever played was at Troubadour Club in Los Angeles that was kind of a hangout like the Bitter End in New York. And I think at the time, there were -- there was more people looking for new blood, because I got a lot of offers just off of performing there.

And eventually Harry Dean Stanton gave me a script. I didn't even know he was an actor at the time. I thought he just sang in the bar there at the Troubadour. But he helped me do a screen test for a film that was called "Cisco Pike." And I got to putting my music in it. And I was the lead in it, in a film with Gene Hackman and Karen Black and Harry Dean.

And it just went on from there.

GROSS: Compare the roles that you get now with what you got early on. You're often playing the heavy now.

KRISTOFFERSON: Yes, I think that's thanks to John Sayles...

GROSS: And "Lone Star."

KRISTOFFERSON: In "Lone Star," yes, I...

GROSS: Yes, where you played a sadistic sheriff.

KRISTOFFERSON: Yes, it was so different from most of the roles that I'd played before that, that I think people finally thought I was acting. (laughs) I'm not sure anybody thought that I ever acted before then.

GROSS: (laughs) Well, I thought I'd play a short scene from "Payback," which just came out on video. And in this movie, Mel Gibson is a con man who's getting revenge on the people who conned him out of $70,000 and also shot him and left him for dead.

You play somebody who heads a crime syndicate. And Mel Gibson has kidnapped your son and is holding him hostage until you deliver the $70,000. But now you've got Mel Gibson tied up, and you're trying to get him to tell you where he's holding your son. And here you are threatening him.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "PAYBACK")

KRISTOFFERSON: Here it is. Hundred and thirty thousand. That's as close as you're ever gonna get to it. But I'll make you a deal. Tell me where John is, and I'll finish you quick. I promise you won't have to find out what your left ball tastes like.

But if there's even a bruise on him, I'll make this last three weeks. I'll give you a blood transfusion to keep you alive if I have to.

Where is he?

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: That's Kris Kristofferson in a scene from "Payback."

How'd you get this part?

KRISTOFFERSON: Well, they had actually finished the film, and apparently weren't satisfied with the way it worked. And they created this character for me to play, and I went in and shot a week, and I told Mel, I said, "You know, there's no -- not any pressure on me. The whole film doesn't work, and you're expecting me to repair it in a week." (laughs)

GROSS: (laughs)

KRISTOFFERSON: But I think I got it because of playing Charlie Wade, you know, in the "Lone Star."

GROSS: I would imagine it's a lot of fun to be in a movie like this, in which there's a lot of really good, snappy, hard-boiled writing.

KRISTOFFERSON: Yes, it was. And good people, you know, like my friend James Coburn and Mel Gibson, you know. It was -- I liked the whole script. I liked it from the moment he walked up and took the money out of that beggar's hat. (laughs)

GROSS: Yes, yes, yes. (laugh) It's a really well-written and directed film.

KRISTOFFERSON: Yes.

GROSS: It also must be fun to be terrorizing Mel Gibson. (laughs)

KRISTOFFERSON: Yes, well -- (laughs) Well, I don't know, it was so late at night when we did that, I -- my brain sort of locked up there for a while, and I can remember he was sit -- it was, like, 4:00 in the morning, and he was sitting there with his -- painfully in the chair while that guy was smashing his toes with a hammer, you know.

And I sort of just -- my brain was paralyzed for a moment there. I said, "You know, this usually happens to me about once in every film. I get to a point where I just can't imagine that I'll ever act in anything again, that I find myself uniquely unequipped to be an actor." (laughs)

GROSS: (laughs)

KRISTOFFERSON: I says, "But usually it takes longer to get to it than this." This was my first night.

GROSS: Did people panic when you said that?

KRISTOFFERSON: Not really. I don't think anybody was afraid that I couldn't do it.

GROSS: Well, I'd like to close with another song from your new CD, "The Austin Sessions." And this is a song called "The Pilgrim, Chapter 33."

Now, this song is quoted in "Taxi Driver." The Cybill Shepherd character, Betsy, buys the record for Travis, the taxi driver played by Robert DeNiro, and she says that he reminds her of the character in the song, and she quotes the line, "He's a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction."

How did this song end up in "Taxi Driver"?

KRISTOFFERSON: I don't know. I always felt like that was the nicest thing that Marty Scorsese ever did to me. (laughs)

GROSS: Well, I guess you had already worked with him in "Alice Doesn't Live Here Any More."

KRISTOFFERSON: I worked -- yes, yes, but I worked -- but I didn't know it was going to be in that one. And God, he had -- there's DeNiro, holding up my album, and they're quoting me like Bob Dylan or something. It was -- I still think that's one of the sweetest things I have ever seen anybody do for anybody in the business.

GROSS: And who did you write the song about?

KRISTOFFERSON: Well, I wrote it about myself and about a lot of friends of mine that I thought were -- you know, Rambling Jack Elliot (ph), Chris Gantry, Johnny Cash, and everybody I knew at the time. And a lot of us were 33 at the time. That's why it's called "Chapter 33."

And Dennis Hopper. I remember when we were down in Peru, every time that you would tell somebody you were 33 years old, they'd say, "Ah, the age of Christ." So that sort of fit the pattern of it.

GROSS: So were you referring at all to how you and a lot of people you knew were kind of self-invented?

KRISTOFFERSON: Oh, yes. Yes. Partly truth and partly fiction, you know. I've always felt that I and many of the people I admire are figments of our own imagination. I always felt that Willy (ph) Nelson, Muhammad Ali, were particularly successful at that, at imagining themselves and living up to what they imagined themselves to be.

GROSS: And your...

KRISTOFFERSON: I remember when I first saw Muhammad Ali, he was Cassius Clay, he was a little skinny light heavyweight over in Rome. And he was telling everybody he was going to be the biggest, the best, you know, he was the next Joe Louis. And, oh, he imagined himself right up into that.

GROSS: Do you feel you did that too?

KRISTOFFERSON: I think I did. When I think back to when I first was writing my first songs, you know, like when I was 11 years old, down in Brownsville, Texas, I think that I imagined myself into a pretty full life after that. I was certainly not equipped by God to be a football player, but I got to be one. And I got to be a Ranger and a paratrooper and a helicopter pilot, you know, and a boxer, and a lot of things that I don't think I was built to do. I just imagined them.

GROSS: Kris Kristofferson. His new CD, "The Austin Sessions," features new versions of his best-known song, including the song that's quoted in "Taxi Driver."

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "TAXI DRIVER")

ROBERT DeNIRO, ACTOR: You want to go to a movie with me?

CYBILL SHEPHERD, ACTRESS: I have to go back to work now.

DeNIRO: I don't mean now, I mean, like, another time, though?

SHEPHERD: Sure. You know what you remind me of?

DeNIRO: What?

SHEPHERD: That song by Kris Kristofferson.

DeNIRO: Who's that?

SHEPHERD: Thee songwriter. "He's a prophet, he's a prophet and a pusher, partly truth, partly fiction, walking contradiction."

DeNIRO: You saying that about me?

SHEPHERD: Well, that's what I've been talking about.

DeNIRO: I'm no pusher. I never have pushed.

SHEPHERD: No, no. Just the part about the contradictions. You are that.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

(AUDIO CLIP: EXCERPT, "THE PILGRIM, CHAPTER 33")

GROSS: Coming up, linguist Geoff Nunberg on how advertisers appropriate youth slang.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Kris Kristofferson

High: Singer and actor Kris Kristofferson can be seen in the recent John Sayles movie, "Limbo." He discusses his acting career and his first album out in about five years, "The Austin Sessions."

Spec: Music Industry; Movie Industry; "The Austin Sessions"; Kris Kristofferson

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: An Interview with Kris Kristofferson

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: SEPTEMBER 07, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 090703NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Youth Slang for Adults

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:52

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: As the new school year starts, our linguist, Geoff Nunberg, has been thinking about youth slang and how adults try to keep up with it.

GEOFF NUNBERG, LINGUIST: What are we up to by now, gen Z? It's September, and the registration lines at colleges are filling up with the new freshmen of the class of -- are you ready for this? -- 2003.

By way of helping its faculty get their heads around that number, Beloit College has assembled its annual list of how students born in 1981 differ from their elders in their frame of reference.

For them, John Lennon and John Belushi have always been dead. The musical "Cats" has been on Broadway all their lives. And Yugoslavia has never existed.

And the students have replied with their own list of things that they know about that their elders don't, trapper keepers, Tina Yothers, wax on, wax off.

Of course, you could have made lists like this for any generation in the past. Still, there's one thing that does make the class of 2003 different from earlier generations. They've never known what it was like to be young in an age when older people didn't hang on their every word.

What brought this to mind was a piece in "The New Yorker" a few weeks ago about a pair of young marketing consultants who specialize in taking corporate clients on guided tours of the youth culture of New York's outer boroughs. They'll take a group of Ford executives from Detroit, say, and give them a quick immersion course. They warn them off wearing Dock shoes and pink polo shirts, and they teach them a little current slang, use "wack" (ph) to mean bad, and "dope" to mean good.

Then they all go off to visit hip-hop stores and pass out free CDs to lure kids into stopping to talk about their language, their fashion, and, by the bye, the brands they like.

Thee tour has evidently become the latest hot ticket in the world of marketing.

The kids in the class of 2003 may find it surprising to know that there was a time when this would have been considered a pretty weird thing to do. For the last 300 years, it's been a part of the natural course of getting older that at a certain age you stop using your own slang and start deploring the slang and habits of the next generation.

Jonathan Swift condemned the slang of the young fops of his period as "barbarous mutilations." Victorians liked to compare slang to a pestilence. Around 1850, Dickens' friend George Salah (ph) described it as "sewerage." And 50 years later, another writer compared the fashions and slang of young people to "the mud and slime that is brought to the surface by the stir of the lower life from the saloon and the gutter."

By the 20th century, older people had begun to lighten up a little on youth and its language, but they were still pretty critical. H.L. Mencken ridiculed flapper slang and described the flapper as "a young and foolish girl full of wild surmises and inclined to revolt against the precepts of her elders."

And 30 years later, the culture of '50s rock and roll evoked reactions that ranged from hysteria to comic ridicule. Frank Sinatra was quoted in "Thee San Francisco Examiner" as calling rock and roll "the martial music of sideburned delinquents all over the earth."

I have my doubts as to whether he actually uttered those very words, but there's no question he shared the sentiment.

Another critic deplored the tendency of white youth to adopt "a slang full of coarse Negro phrases." And on a lighter note, Steve Allen did a regular shtick on his weekly comedy show giving poetic readings of the lyrics to rock 'n' roll songs like "Rama Lama Ding Dong," a song that was by the Edsels, whose name presumably had no endorsement from the Ford management of that period.

It's hard to pick the exact moment when all of this invective started to wind down. Some people would point to the Beatles and Dylan, when the language, music, and culture of young people began to appeal to a general audience. Or maybe the turning point came a little earlier than that, in 1961, when Joey D. and the Starlighters released "Peppermint Twist," and middle-aged New Yorkers began to line up outside the doors of the Peppermint Lounge. Or you could pick the year 1968, when "Hair" opened on Broadway.

It took a while for the tirades to die out, of course. In the '60s, there were still people denouncing the Twist as a "jungle dance," and people said similar things about the dress and language of Woodstock a few years later.

In the end, though, all these condemnations were doomed to fade away under the benign tolerance of market capitalism. You can still find people who deplore the way kids dress and talk nowadays, but it's a safe bet they don't work for Ford or Nike or the Gap.

It has to leave you feeling a little sorry for those kids who are lined up at the college registration desks. Whatever they wear, whatever they say, there's no one left to scandalize. There's no style they can come up with that the marketeers can't appropriate, repackage, and sell back to them with an air pump in the tongue.

There's nowhere to hide when Microsoft and Motorola are all over them hawking cool stuff. Maybe that's why today's young people have been driven to tattoos, piercing, and general self-mutilation. At least those aren't signs you can stick a brand on.

GROSS: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center.

FRESH AIR's interviews and reviews are produced by Naomi Person, Phyllis Meyers (ph), and Amy Sallett, with Monique Nazareth and Anne-Marie Boldonado (ph). Research assistance from Sarah Scherr (ph). Roberta Shorrock directs the show.

I'm Terry Gross.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Geoff Nunberg

High: Linguist Geoff Nunberg discusses slang.

Spec: Lifestyles; Youth; Education

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Youth Slang for Adults

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.