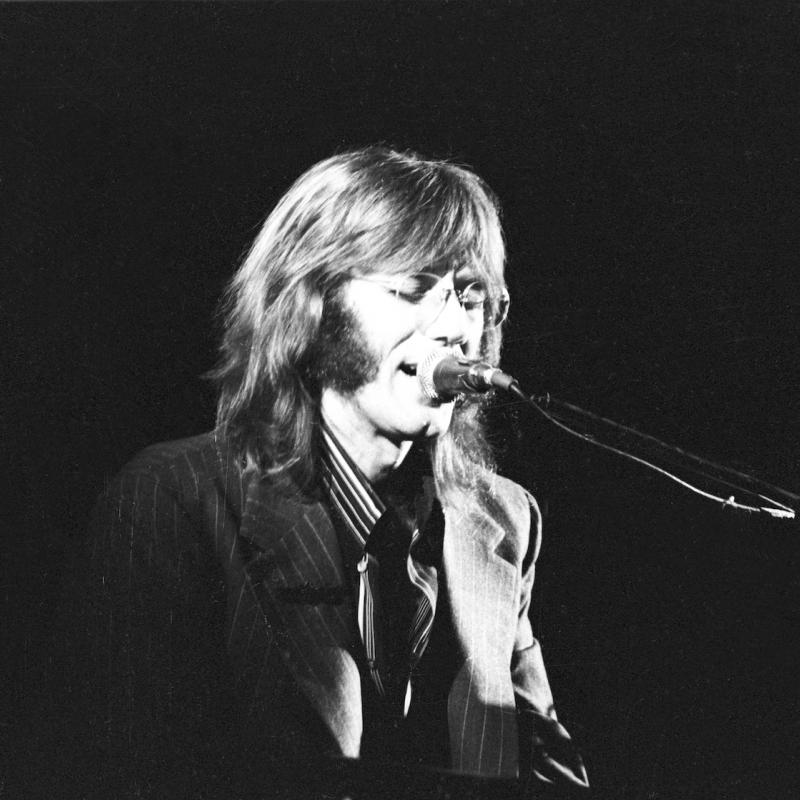

Remembering Ray Manzarek, Keyboardist For The Doors.

The mythology surrounding The Doors generally centers on its lead singer, Jim Morrison. Morrison is still considered one of rock's tortured poets, but The Doors' sound was based largely on Ray Manzarek's keyboard playing. His are the riffs immortalized in songs like "Riders on the Storm."

This interview was originally broadcast in 1998.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on May 24, 2013

Transcript

May 24, 2013

Guest: Ray Manzarek - Marcus Samuelsson

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, in for Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: Ray Manzarek, whose keyboard work helped define the distinctive sound of the '60s rock band The Doors, died Monday in Germany after a long battle with cancer. He was 74. Manzarek was raised in Chicago and grew up with a passion for jazz and blues. He kept that passion in his keyboard work as he shaped the sound of the band that backed Jim Morrison.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: The Doors had a string of hits between 1967 and Jim Morrison's death in 1971. After the demise of The Doors, Manzarek recorded with a band of his own called Nite City and in the '80s produced four albums for the L.A. punk band X. Terry spoke to Ray Manzarek in 1988 and invited him to sit at the piano during their conversation. He'd written a memoir called "Light My Fire: My Life with The Doors."

Manzarek and Jim Morrison attended UCLA film school together but didn't think of forming a band until they were both out of school.

RAY MANZAREK: Biblically, 40 days and 40 nights after we said our goodbyes after graduation, I'm sitting on the beach wondering what I'm going to do with myself. Who comes walking down the beach but James Douglas Morrison, looking great, lost 30 pounds, was down to about 135, six feet tall, Leonardo - Michelangelo's David. He had the ringlets and the curly hair starting to kind of fall over his ears in gentle locks.

And I thought, God, he looks just great. And I said Jim, Jim, come on over here, man. And I said, well, what have you been up to? So what's going on? And he said, well, I've been living up on Dennis Jacobs'(ph) rooftop, consuming a bit of LSD and writing songs.

I said, whoa, writing songs, OK, man, cool, like sing me a song. You know, he said, oh, I'm kind of shy, because I knew he was a poet, he knew I was a musician. I said sing me a song. So he sat down on the beach, dug his hands into the sand, and the sand started streaming out in little rivulets, and he kind of closed his eyes, and he began to sing in a Chet Baker, haunted whisper kind of voice.

He began to sing "Moonlight Drive," and when I heard that first stanza, let's swim to the moon, let's climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hide, I thought ooh, spooky and cool, man. I can do all kinds of stuff behind that. I could do kind of...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: Sort of let's swim to the moon, you know, let's climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hide. And I thought ooh, I can put all jazz chords, and I can put some kind of bluesy stuff.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: I thought yeah. And I could do my Ray Charles and my Muddy Waters, Otis Spann influences, and I could do just all kinds of bluesy, funky stuff behind what Jim was singing. And then he had a couple of other songs, "My Eyes Have Seen You," and "Summer's Almost Gone," and they were just, they had beautiful melodies to them that would just allow for chord changes and improvisations, and I said, man, this is incredible, let's get a rock and roll band together.

And he said that's exactly what I want to do. And I said all right, man. But one thing: What do we call the band? It's got no name. We can't call it Morrison and Manzarek, I mean, you know, M&M or, you know, Two Guys from Venice Beach or something. He said no, man, we're going to call it The Doors.

And I said the what? That's ridiculous, the - oh, wait a minute, you mean like the doors of perception, the doors in your mind.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And the light bulb went on, and I said that's it, the Doors of Perception. He said no, no, just The Doors. I said like Aldous Huxley. He said yeah, but we're just The Doors.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And that was it. We were The Doors.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And that's how the band got formed.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "MOONLIGHT DRIVE")

THE DOORS: (Singing) Let's swim to the moon, uh-huh, let's climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hide. Let's swim out tonight, love. It's our turn to try, parked beside the ocean on our moonlight drive. Let's swim to the moon, uh-huh, let's climb through the tide...

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

So when you and Jim Morrison decided to create a band, that left the lead singer and keyboard player. You still needed other musicians. So you ended up finding the drummer, John Densmore, and guitarist Robby Krieger. But you became not only the keyboard player but the bass player too.

MANZAREK: Well, that was of necessity.

GROSS: Tell us that story.

MANZAREK: We had the four of us. I found John and Robby in the maharishi's meditation.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And kind of Eastern mysticism. We were into the same thing, the yoga, the same kind of yoga that The Beatles were into, and that came out of the song - the song "This is The End" comes out of that. So we were all seekers after spiritual enlightenment, and so was Jim, of course. But we didn't have a bass player.

So I applied my boogie-woogie background, my rock and roll boogie-woogie, because when discovered boogie-woogie, that was the whole thing.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And you just keep that left hand going. You don't do anything with it. It just goes and goes and goes and goes.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And the right hand does the improvisations.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: So I had done that over and over and over as a kid, so it was very easy for me to once we found the Fender Rhodes keyboard bass, 32 notes of extra low-sounding low notes, it was very easy for me to do...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: So that's what I did on the piano bass.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: Or like "Riders on the Storm."

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And that's what I did, I just over and over, repetitive bass lines that are just like boogie-woogie, it just keeps on going. And it becomes hypnotic, and that was - that's why lefty here is, thank you, he did a very good job. He's not too quick, a bit of a slow-witted fellow, lefty, but he's really strong and solid and plays what he has to play, so lefty became our bass player.

GROSS: One of the really big stories in the lore of The Doors is the concert in Miami where...

MANZAREK: Yes it is.

GROSS: ...where many people say that Jim Morrison exposed himself.

MANZAREK: Yes, they do.

GROSS: And you say he didn't exactly. But he had seen The Living Theatre a few days before and that was like the theater group was experimenting with, you know, breaking down the fourth wall and taking off their clothes in the middle of theater performances, confronting the audience and so on.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: And he was influenced by that.

MANZAREK: Yes, he was. We're in Miami. It's hot and sweaty. It's a Tennessee Williams night. It's a swamp and it's a yuck - a horrible kind of place, a seaplane hangar - and 14,000 people are packed in there, and they're sweaty, and Jim has seen The Living Theatre and he's going to do his version of The Living Theatre in front of - this is the first time he's been home.

He was born in Melbourne, Florida. This is his - virtually his hometown and he's going to show these Florida people what psychedelic West Coast shamanism and confrontation is all about.

He takes his shirt off in the middle of the set and says, you know, you people haven't come to hear a rock and roll - he's drunk as a skunk, and he didn't tell any of us what he was going to do. If only he have told somebody. He said you didn't come to hear a rock and roll band play some pretty good songs. What you came - you came to see something, didn't you? And they're all going - errrrrrrr.

He said what's you come to see? You came to see something that you've never seen before, something greater than you've ever seen. What do you want? What can I do for you? And the audience is going like this, you know, that's how the audience, it's just rumbling and rumbling. And he said OK, how about if I show you my - and all the audience goes screaming crazy.

It was like madness, and Jim takes his shirt off, holds it in front of him, reaches behind it and starts fiddling around down there, and you wonder what is he doing. And I'm thinking, oh God, he's going to take it off. And the audience is getting crazier and crazier. And then Jim whips the shirt out to the side, he said did you see it, did you see it? Look, I just showed it to you. Watch, I'm going to show it to you. Now, keep your eyes on it folks and he whips it out...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: Off to the side again.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: Off to the side again, off to the side and says, I showed it to you. You saw it, didn't you? You saw it, and you loved it, and you people loved seeing it. Isn't that what you wanted to see? And sure enough, it's what they wanted to see.

They hallucinated. I swear, the guy never did it. He never whipped it out. It was like, it was like in the West Coast, Jesus on a tortilla. It was one of those mass hallucinations. It was - I don't want to say the vision of Lourdes because only Bernadette saw that, but the other people believed and maybe other people said - it was one of those kind of religious hallucinations, except it was Dionysus bringing forth, calling forth snakes.

GROSS: And then you say he said to the audience, come closer, come on down here. Get with us, man.

MANZAREK: Oh, yeah, yeah. Come on, yeah, oh, come on. Sure, come on. Join us. Join us on stage. And eventually, the - sure, and they started coming on a rickety little stage, and the entire stage collapsed. Sure.

GROSS: What were you thinking?

MANZAREK: It's chaos. It's the end of the world as we know it. It's rock and roll. It's madness. It's the end of Western civilization. Dionysus has come back from 2,000, 3,000 years ago. He has called forth the snakes. The people have had a mass hallucination. They've rushed the stage trying to get their hands on Dionysus to rip and tear him apart, and I played...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: I played the riot. John and Robby left the stage, and I just played screaming, crunching organ all over the place, just the way I did when my first piano lesson - before the piano lesson when my mom and dad said play the piano, and I went...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: I did the exact same thing on the organ. I was seven years old going yaaaah and screaming on the organ.

GROSS: Was there a part of you that was saying instead of like, blah, blah, blah, Dionysus, was there a part of you that was saying my stupid buddy Jim Morrison is creating this madness, we'll be lucky if we get off the stage alive?

MANZAREK: There was a part of me that was saying we are going to get in big trouble, we're in trouble here. But you know what? It's too late to stop it.

(LAUGHTER)

MANZAREK: So why not treat it as a theatrical event, you know? But we're going to get in serious trouble, and sure enough within a week Jim had been arrested, he had been charged with indecent exposure, public profanity, open profanity, public drunkenness, lewd and lascivious behavior, and - and they read this in court - and simulation of oral copulation.

He did take is penis out and shake it.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: In the courtroom, the audience is going ehhhhhh, judge going order in the court, order in the court here. And once they read that in court, I knew it was a total fiasco because he had never done it. He didn't do it.

DAVIES: Ray Manzarek of The Doors, speaking with Terry Gross in 1998. We'll hear more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're listening to Terry's interview with keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who died on Monday. They spoke in 1998 when Manzarek's memoir, called "Light My Fire: My Life with the Doors," was published.

GROSS: In your memoir you write a little bit - you write a lot, really, about how The Doors developed their sound and how you developed your sound as the keyboard player with the group. Let's take an example of one of those songs. Why don't we look at "Light My Fire," which is...

MANZAREK: Sure.

GROSS: ...probably the most famous or one of the most famous.

MANZAREK: The most famous Doors song.

GROSS: Sure. Yeah.

MANZAREK: Yeah, probably the most famous Doors song. You know, it's that worldwide popular appeal, the most famous. And Robby Krieger is actually the writer of "Light My Fire." So the way we would work on songs is somebody would bring a song in and then everyone would go to work on it. It would be like little bees just - or little things spinning and working and weaving.

So Robby came in with a song, he said I got a new song called "Light My Fire," the first song Robby Krieger ever wrote. What a genius he is. He's just the greatest guy, a great guitar player and great songwriter. I've got a song called "Light My Fire." So he plays the song for us and it's kind of a Sonny and Cher kind of...

(Singing) Da, da, da, da, da, da, da, da, da. Light my fire.

And it's like, OK. OK. Good chords change - what are the chord changes there? And he shows me an A minor...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: ...to an F sharp minor.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And that's like, whoa, that's hip.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: That's cool. And then...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And that's when he went into the Sonny and Cher part.

(SOUNDBITE OF HUMMING)

MANZAREK: I say, no, no, no, no, no, no, we're not going to a Sonny and Cher kind of song here, man. And that was popular at the time. Densmore says, look, we've got to do a Latin kind of beat here. Let's do something in kind of a Latin groove.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And I'm doing this left-hand line. So John is doing ka-chinka-chinka-dunka. And we set up this Latin groove and then go into a hard rock four...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And Robby's only got one verse, he needs the second verse, and Morrison says, OK, let me think about it for a second. And Jim comes up with the classic line: And our love becomes a funeral pyre. You know, you know that it would be untrue, you know that I would be a liar if I were to say to you, girl, we couldn't get much higher, is Robby's. And then Jim comes: The time to hesitate is through. In other words seize the moment, seize the spiritual LSD moment. The time to hesitate is through, no time to wallow in the mire. Try now, we can only lose.

Whoa, that's kind of heavy - try now, we can only lose, meaning the worst thing that can happen to you is death, and our love becomes a funeral pyre, our love is consumed in the fires of (unintelligible) and it's like, God, Jim, what a great, great verse, man.

So we've got verse, chorus, verse, chorus, and then it's time for solos. So anyway, the verse goes...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: You know how that goes. You've heard it a million times. And then into the chorus...

(Singing) Come on baby light my fire.

So it's time then for some solos. We've done a verse, chorus, verse, chorus. Now what do we do? We've got to play some solos. We've got to stretch out. Here's where John Coltrane comes in. Here's where The Doors' jazz background - John's a jazz drummer. I'm a jazz piano player. Robby's a flamenco guitar player. And we all said, you know, we're in A minor. Let's see. What do we do?

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: It ends up on an E, so how about...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: "My Favorite Things," John Coltrane. It's "My Favorite Things," except Coltrane's doing it in D minor.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: But the left hand is exactly the same thing. It's in three, one, two, three, one, two, three, A minor. The Doors' "Light My Fire" is in four. We're going from A minor to B minor.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: So it's the same thing as...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And that's how the solo comes about. And then we just go...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: So it's John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things." And Coltrane's "Ole Coltrane," and then...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: That's the chord structure. Then I would solo over it, Robby would solo over it, and at the end of our two solos, we'd go into a - a three against four.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And I'm keeping the left hand going exactly as it goes. That hasn't changed. That's the four. On top of it is three.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And into the turnaround.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: And we're back at verse one and verse two, and we're back into our Latin groove. So it's basically a jazz structure. It's verse chorus, verse chorus, state the theme, take a long solo, come back to stating the theme again. And that's how "Light My Fire" came about. The only thing left to do was to come up with that little turnaround thing. I hadn't had that yet.

And we said, now, how do we start the song? Do we just jump on A minor to an F? Should we - are we going to do that, vamp a little bit? I said no, no, no, we need something more. We can't just vamp a little bit. And I started this, I took my Bach back to work, put my Bach hat on and came up with a circle of fifths. So I started like this...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: Like a Bach thing, like...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: So same kind of thing.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MANZAREK: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, B flat. I'm on - so I'm in G, D, F, up to B flat, E flat, A flat to the A to A major, A major, yeah, that's it, and then we'll go to the A minor. I'm thinking all this to myself. So that's how the introduction came about.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "LIGHT MY FIRE")

MANZAREK: F, B flat, E flat, A flat, A - and the drums and everything. Jim comes in singing. And the Latinesque and then into hard rock. So that's how "Light My Fire" goes. That's the creation of "Light My Fire."

DAVIES: Ray Manzarek on FRESH AIR, recorded in 1998. That was when his memoir about his life with The Doors was published. Manzarek died Monday. He was 74. I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, in for Terry Gross. Chef Marcus Samuelsson, owner of the acclaimed Red Rooster restaurant in Harlem, recently received a prestigious James Beard Award for his memoir, called "Yes, Chef," which is now out in paperback. The book's, in part, about what it takes to be a master chef - the insults and abuse suffered in training, and the demands of running a business.

It's also, in part, the story of his remarkable life. He was born in rural Ethiopia, and orphaned at age 3, when his mother died in a tuberculosis epidemic. Samuelsson and his sister were adopted by a Swedish couple, and raised there. He trained in some of Europe's finest restaurants before eventually making his way to New York. Marcus Samuelsson has written several cookbooks. I spoke to him last year, when "Yes, Chef" was published.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

DAVIES: You know, when you think of people who are accomplished athletes - I mean, they've learned a technique, and they have trained. But they also began with natural ability; you know, speed and reflexes, and hand-eye coordination. And I'm wondering, do chefs, do you think - are they born with certain natural abilities, which give them, you know, the tools they need to develop that craft?

MARCUS SAMUELSSON: That's a great question. I do think that it's a combination of both, right? A chef is part an athlete, as you explained, but it's also an artist, but it's also this wonderful thing with curiosity and craftsmanship. If you're not curious and want us to keep evolving, it's not going to happen.

But you also have to protect and develop a sense of taste, right. It's such a specific job, being a chef, because people want to know your opinion, how you're going to approach this piece of salmon, how you're going to approach the asparagus in spring. It's nothing generic.

I do think, you know, for me, certain things I was born with was this desire of being connected to food, again looking here from when we didn't have any food also looking from my grandma's time where really the two world wars was really like, you know, she didn't have a lot, either. So she had to make a lot.

But then being a chef, where you're around the best ingredients possible. So all these threes were very important for me, for my narrative of being a chef.

DAVIES: So you worked at a restaurant, you went to a cooking school in Sweden, then you went to one of the better restaurants in the country. Then you went to Interlaken in Switzerland and from there other places.

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: Do you want to describe maybe one of the more colorful chefs that you worked for? There was this character Paul Griggs(ph) who I think was an Englishman, right?

SAMUELSSON: Yes, I mean, what - coming to Switzerland for me was life-changing because for the first time, I was in a truly international place. I mean, the guests were Americans or Swiss or Japanese or come from, you know, Dubai. So you always had to execute at the highest level. So you were taught right away very, very high standards. And this kitchen was run by an incredible chef called Herr Stokar.

And he was this classic sort of French chef that you think about. He was - he spoke both German, Swiss-German, French, English. He spoke every language. And Paul, that was my chef that was truly the guy that was - the sous chef in my section of the kitchen, he was very...

DAVIES: Sous chef meaning what, like a deputy chef?

SAMUELSSON: Yeah, sous chef, the word sous is under, it means under the main chef, right, so it's right under the executive chef. Every day, you know, you could get fired. Every day you were up for being fired. And Chef Paul's job was to prepare his section so Mr. Stokar, the big chef, could never walk into our section and so Mr. Paul would never get embarrassed, right.

And so it was completely top-down in fear, but it's also about discipline and love for the ingredients and respect for the guests. So, you know, I choose to look at all of this rigid training as a mass blessing to me because it gave me discipline, which is very important, which gave me incredible amount of work ethic, which you have to have, and you become very humble, and you learn a lot.

DAVIES: I think a lot of people, perhaps from cooking shows and things like Chef Gordon Ramsey picture the typical executive chef as this, you know, kind of raving semi-lunatic. I mean, how common are those kind of outbursts of temper in the kitchen?

SAMUELSSON: Well, I mean, you know, chefs are very colorful, and back in the day, you could basically treat your employee however you wanted. You know, I've got plates thrown at me, I've got scallop marks in my face that I got thrown at me.

But not for one second would I challenge the chef for that. I was in. I was committed. And I knew that these guys, these incredible master chefs from France, from Germany, from Switzerland, sat on that sense of knowledge, and that humbling - it was a humbling experience.

This was also about not being seen but just getting the work done. I took pride in not being fired. When we made mistakes, the chef just looked at you and said you're fired, almost like in a Donald Trump show or something like that. But and I just wanted to make sure that I would not be on that - I would not get the pink slip.

DAVIES: There's so much going on in a kitchen and so many skills to learn, from how to, you know, be careful and pick just the right ingredients to how to kind of cut them and slice them and the techniques of cooking and searing and all this stuff. Can you think of an example in one of these apprenticeships where someone taught you something, and you said wow, that's it, that's important, I get this?

SAMUELSSON: Oh absolutely. You know, in Switzerland, I had this chef that taught me how to break down a lamb completely and not like when you look at the bones, when you debone the whole lamb that the meat and the pieces of meat was completely separated, and the bone of the lamb was completely just - it was almost like a surgeon, you know.

And he was just laughing at me, and he was calling me all kinds of names, and I just knew, if I'm just going to be quiet and just keep having him screaming in my ear, and I'll just watch and become a really good studier of a craft, I'm going to know in two months how to make that, to debone a whole lamb.

And that's something that I can take with me for the rest of my life. So who cares? It's a fair tradeoff. If he wants to yell at me, I'll take it.

DAVIES: Now, you also did a couple of tours on a cruise ship, cooking on a cruise ship.

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: Now that's, I think, a very different kind of experience. What did you get out of that?

SAMUELSSON: I saw the world for the first time. I always wanted to see the world. I learned how to eat really good Filipino food because the Filipino crew cooked incredible food at the crew mess every day. But I also realized for the first time that all the great food was not owned by Europe.

There were places like Singapore. There were places like Acapulco, wonderful places in South America. Yes, the food that I'm so passionate about could come from Europe, specifically from France, but it could also come from a wonderful sort of taqueria y Fonda in Mexico that didn't exist - of course it existed for generations but not in our vocabulary as chefs , that street food could be just as yum and delicious as the highest art of French cooking.

DAVIES: So you were learning your lessons about tastes and flavors not from what you were making for the guests on the cruise...

SAMUELSSON: Absolutely.

DAVIES: But what you were getting going ashore at street stands.

SAMUELSSON: Absolutely, and I learned incredible, again, work ethic. On the cruise ship, we worked breakfast, lunch and dinner seven days a week for five months, right? So then you do that, breakfast, lunch and dinner seven days a week, you know, you become - your skills get honed every day. You train, and it's very tough, it's very, very tough.

DAVIES: Marcus Samuelsson's memoir is called "Yes, Chef." We'll talk more after break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR and we're listening to my interview recorded last year with Chef Marcus Samuelsson. His memoir "Yes, Chef" has just won a James Beard Award.

You got to New York and started at this restaurant, Aquavit. You want to tell us a little bit about that place?

SAMUELSSON: I got to New York and Aquavit and Aquavit at this time was very well-known in Sweden. It was a big deal like for us as Swedes to have a restaurant in New York City, and this was such an amazing time. It was just also the development really, what I think of these New York chefs, like, you know, Jean Georges was very young, Danielle, Alfred Portale, Bobby Flay was just coming up, so the city was just bustling with these young chefs - American chefs, also and French chefs sort of figuring out what should the New York food scene look like. So to be there in the middle of all that, watching this sort of in front of me but also being eventually becoming part of that is an amazing journey, you know, the fact that we got three stars after I became a chef was obviously a big deal. I became the executive chef because the chef before me, Jan Sendel, passed away...

DAVIES: Right. That was quite a remarkable story. You at the age of 24...

SAMUELSSON: Yeah.

DAVIES: ...became the executive chef of this really well - well, quite well-regarded restaurant.

SAMUELSSON: Absolutely.

DAVIES: And then the big break was when you got a three star review, I think it was from Ruth Reichl. Is that right?

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: And that was a huge thing for you to get a three star review from The New York Times. At this point you had become to develop some of your own innovative stuff. What were some things you were cooking dinner there that was - that you...

SAMUELSSON: Well, it was always for me about keep asking myself questions: Will I be this young cook that would just take in these French dishes and doing it? And I was like, no. I refuse that. I have to have authorship in my food. I have to figure out what is me, what is my story, what is my take on this. And I started to build up this Scandinavian building block, where we were really pickling and preserving, you know, this sort of it has to be a strong narrative of seafood in there. Game was very, very important because that's what we grew up with, a lot of game meat. So game meat, pickling and preserving and this sort of balance between sweet and sour and seafood became sort of pillars that I hung up every day showing. So a dish could be like salt cured duck with potato pancake and lingonberry ginger vinaigrette, that would have been a duck dish that would have been an appetizer back then. And, you know, I salt cured it the way my grandmother taught me. I seared it the way I was taught in France. The lingonberry jam I knew how to do but I added in more ginger the way I may be experienced it in Asia. And the potato cake was roasted the way I've seen them similar in Switzerland.

DAVIES: The other thing you write about is how you spent all of this time going through Chinatown and other parts of New York picking up new flavors.

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: I mean you also went to Ethiopia and became reacquainted with the land of your birth and got Ethiopian dishes and spices. I mean that's a lot of stuff to bring together, isn't it?

SAMUELSSON: Well, you know, first of all, I mean I fell in love with Aquavit but I also fell in love with New York and all of New York - that other New York, Queens, Brooklyn and Chinatown. And Chinatown spoke to me so well because there's something that I've experienced in other places on the boat, but to have one place to go down to and constantly be put in front of ingredients that I wasn't familiar with, that was my way of wow, being curious and saying wow, what happens if I take jackfruit and put it on a sorbet? Sometimes good. Sometimes not so good. What is galangal, because I've had this flavor before to Kaffir lime leaf in a sorbet and so on. So the narrative of non-European food spoke to me, probably because I came from Africa but I didn't know where to get it from. And Asia then became, the Asian and the Chinese culture and going to K-Town, Koreatown, on 32nd Street, became these places for me where I could just wow, buy a bunch of ingredients, try them out in my kitchen at Aquavit and eventually put them on the menu. You know, it became a lab and, you know, it was driven with a lot of love and passion.

Getting to Ethiopia was much later and I felt that it was time for me to start, you know, when in New York when an Ethiopian person responded to me I didn't know that, first of all. Why are you talking to me? I felt like wow, I'm Swedish. But, of course, for any person who is in New York City, when they look at me they see I'm an Ethiopian man. So it took me a while. So I really learned about Ethiopia from the Ethiopian community here in New York and then eventually I warmed up to the idea of you know what? I have to learn more about myself.

DAVIES: I have to ask you about the honor of being chosen to cook for President Obama's first state dinner.

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: You want to talk a little bit about developing that menu?

SAMUELSSON: I remember that first development menu that we made; I just started to ask myself questions, you know, it's for the Indian prime minister. I also watched, you know, the evolution of Michelle Obama's wonderful initiative with the garden. So I started thinking about the food, not necessarily as like what will be the best food that I cook but actually from a serving point of view wouldn't it be better if it will be something that speaks towards India? Something that speak towards her commitment to the garden? Wouldn't it be better to do something that highlights America and American wines because I looked a little bit at former state dinners and they were all French food whether they, you know, and that I think makes sense if it's a French prime minister coming, but not necessarily for the Indian prime minister. So our state dinner was historical in many ways. It was Obama's first but it was also the first time where we really didn't serve French food at the state dinner.

DAVIES: So what was your menu? What did you serve?

SAMUELSSON: Well, the menu, you know, for me it was important also to sort of bring it to the sense of it's a dinner party, right? So we started what could be a better dinner party than breaking bread? So I started with a bread course, which was sort of the first time there. So I have both cornbread and Indian chapatti that you can sort dip in sambal and chutney. And I thought it would envision this way of these people maybe not knowing each other on the table but sort of passing the sense of hey, let's break bread. So we started with the bread course. Then we had a salad course where the salad was actually picked from the first lady's garden.

And then we did a lentil soup. I wanted to make this commitment to humble ingredients that would taste just delicious because it was cooked and prepared with spice in a certain way. So I did red lentil soup and then we had really a vegetarian course, which was pumpkin dumplings with a little bit of tomato, jam and greens or green prawn that was really taken from a New Orleans, was taken from Louisiana.

So we did this sort of beautiful shrimp dish with a curry spices and then we did a pumpkin tart for dessert with an little bit of Indian Garam masala spices, all served with American wines.

DAVIES: We have just a bit of time left and I do want to ask you about the Red Rooster. The restaurant...

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: ...that you've opened in Harlem. Now, one of the interesting things, when you look at the menu you see some Swedish dishes and you see some Ethiopian food, and of course some very traditional kind of soul food things.

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: And I'm wondering when you take something like fried chicken...

SAMUELSSON: Yes.

DAVIES: ...you give it an original take. And that must be tricky because people are, you know, it's a food that people have a great love for in a traditional way. You want to talk about what - what is your fried chicken? What do you do?

SAMUELSSON: Yeah. No, fried chicken was obviously one of the things that you're going to open a restaurant in Harlem - there's about 500,000 people in Harlem; I knew there was about 250,000 fried chicken experts. And I wanted to, again, have some authorship in mine. Right?

So I ate a lot of fried chicken. I started going to a place called Charles in Harlem to try the original and great fried chicken and then I said, OK, what's our take on this? What's going to be my take on this and how are we going to develop it so it's better but yet there's some familiarity?

I looked at fried chicken like a great foie gras from France. Again, how do you have authorship on this? And I started to make some decisions right away. I want to cure it the way my grandmother cure it, in lemon and salt. I want to marinate it with a little bit of African influence, like coconut milk, and buttermilk. And then the chef in me started to think about it.

I've got to fry it on both low and high heat. That's how you get it to cook through and crispy. Now, the flour can be classic flour with a little bit of hint of corn in there, but most and more than anything, spices. So next to the fried chicken I have to create a spice blend. So we call it the chicken shake. The chicken shake has my spice blend and has lots of barberry from Ethiopia.

And all of these different steps, cooking it on low heat to high heat, giving it the chicken shake on top of it, marinate it both in buttermilk and coconut milk, letting it sit in the water and the lemon the way my grandmother did, all of that gives us a authorship and a license to call it the Red Rooster fried chicken.

Specific ways and decisions that we have to take. Otherwise we're not chefs. You have to have a point of view; you have to have a take on a dish like fried chicken.

DAVIES: Right. And one of the details was you fry it in day-old oil? Is that right? Why?

SAMUELSSON: Day-old oil that's been seasoned. And day-old back in the day, because obviously it was cooked before in something so the flavors of what's cooked before took shape in the oil, right? We don't really do it that way. We infuse our oil with a little bit of garlic and rosemary to add lots of great flavors.

DAVIES: So it's not literally old oil; it tastes like it's been around.

SAMUELSSON: Yes, absolutely. Like most good things. Like a good pair of vintage shoes. They feel easier to walk in than a brand pair of shoes.

DAVIES: Well, Marcus Samuelsson, it's been interesting. Thanks so much.

SAMUELSSON: Thank you very much for having me.

DAVIES: Marcus Samuelsson's owns the Red Rooster restaurant in Harlem. His memoir, "Yes, Chef," has won a James Beard Award and is coming out in paperback. Coming up, David Edelstein reviews the films "Frances Ha" and "Before Midnight." This is FRESH AIR.

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: Film critic David Edelstein has a review of two new American independent films. Noah Baumbach's "Frances Ha" stars Greta Gerwig as a free-spirited New York dancer, and Richard Linklater's "Before Midnight" revisits characters played by Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy for their third go-round at finding emotional fulfillment. Here's David.

DAVID EDELSTEIN, BYLINE: Lately, I've been re-watching vintage Francois Truffaut movies, and I've been struck by the resurgent influence on American independent films of the French New Wave of the late '50s and '60s. The Truffaut borrowings are fairly explicit in Noah Baumbach's "Frances Ha," while Richard Linklater's "Before Midnight" takes its cues from Eric Rohmer's gentle, but expansive talk-fests. Mainstream movies seem machine-tooled nowadays, so the impulse to reach back to an age of free-form filmmaking feels especially liberating.

Not that "Frances Ha" isn't also annoying. It's an ode to Baumbach's girlfriend Greta Gerwig, who co-wrote the picture and plays Frances, a would-be dancer not terribly light on her feet - she's adorably galumphy. She's also childlike, almost pre-sexual, holding fast to her apartment-mate and best friend, Sophie, played by Mickey Sumner. They hold hands, sometimes sleep in the same bed.

The movie centers on how grown-up life wallops Frances. She loses the dancing gig that pays her rent. Sophie pulls away. The camera holds on Frances' face as she takes each blow. But she galumphs on. Critics have acclaimed the film as Baumbach's most generous, after a series of hate letters to humankind like "Margot at the Wedding" and "Greenberg." But the old Baumbach condescension to his characters is there, in the way sundry New York snobs fail to recognize Frances' magic.

He's very attached to the notion that for a scene to be dramatic, it has to build to a humiliation. The French New Wave borrowings are hit-and-miss. The black-and-white cinematography is radiant, and I loved the traveling shot of Frances bounding and twirling along a sidewalk. But Baumbach appropriates one of my favorite scores - Georges Delerue's wistful waltz from "King of Hearts" - and periodically cranks it up for quick shots of enchantment.

He does pull off a wonderful trick. He combines - seamlessly - French New Wave exuberance with the homegrown American genre known as mumblecore, in which youngish characters grope to express something definite in a world of indecision. The scenes with Frances and Sophie are messy, wavering in ways I've never seen.

And almost as fine are scenes in which Frances lolls around an apartment she comes to share with two self-indulgent, but funny rich boys. When Baumbach's touch is glancing, when he cuts before the humiliation, the movie zings.

"Before Midnight" is a more daring feat. It's Linklater's third film with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, whose characters Jesse and Celine met on a train in 1995's "Before Sunrise," and got reacquainted under tense circumstances nine years later in "Before Sunset."

This is a very different movie. Jesse and Celine have been together nearly a decade. They live in France and have two golden-ringleted little girls, and the magic of discovery has worn off. Jesse is a successful novelist, and doesn't seem fully present. He escapes into his career and lets Celine tend to the girls. But Celine isn't one to hide her disappointment, or her desire to measure their old life against their new.

(SOUNDBITE OF MOVIE, "BEFORE MIDNIGHT")

JULIE DELPY: (as Celine) Hey. Can I ask you a question?

ETHAN HAWKE: (as Jesse) Sure.

DELPY: (as Celine) If we were meeting for the first time today on a train, would you find me attractive?

HAWKE: (as Jesse) Of course.

DELPY: (as Celine) No, but really, right now as I am? Would you start talking to me? Would you ask me to get off the train with you?

HAWKE: (as Jesse) Well, I mean, you're asking a theoretical question. I mean, what would my life situation be? I mean, technically, wouldn't I be cheating on you?

DELPY: (as Celine) OK. Why can't you just say yes?

HAWKE: (as Jesse) No, no, no. I did. I said of course.

DELPY: (as Celine) No, no, no. I wanted you to say something romantic, and you blew it. OK?

HAWKE: (as Jesse) Oh, oh, OK. OK. All right. Wait. If I saw you on a train, OK, listen. I would lock eyes with you.

DELPY: (as Celine) Uh-huh.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) And I would walk right up to you and say, hey, baby. You are making me as horny as a billy goat in pepper patch.

DELPY: (as Celine) Oh! Stop it. That's disgusting. Billy goat. No. The truth is, OK, you failed the test. And the fact is...

(as Jesse) No!

(as Celine) ...you would not pick me up on a train. You would not even notice me, a fat-ass, middle-aged mom losing her hair.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) OK, losing your hair.

DELPY: (as Celine) Yeah, that's me.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) You set me up to fail on this one.

DELPY: (as Celine) OK. True.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) You did, all right?

DELPY: (as Celine) True, true, true.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) All right. But in the real world, Baldy, OK, on game day, when it mattered, I did talk to you on a train. OK? I did that. It was the best thing I ever did, all right?

DELPY: (as Celine) Really?

HAWKE: (as Jesse) Yeah.

DELPY: (as Celine) Look at the goats.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) Hey.

DELPY: (as Celine) Hello.

HAWKE: (as Jesse) Yeah.

EDELSTEIN: Hawke and Delpy worked with Linklater on the script, and when you watch these exchanges - which zig and zag, in lengthy, single takes - you almost believe they're thinking up the lines as they go along. The film is set on a Greek island, where they're on holiday, and like Eric Rohmer, Linklater uses the landscape - here cliffs and crags and ancient buildings - to underscore Celine's longing for permanence and Jesse's for flight.

He wants to move to Chicago to be closer to his son from a previous marriage. Celine, who feels increasingly erased, isn't so sure. Movies are full of people meeting and marrying. They're full of tortured breakups. The middle ground of "Before Midnight" is less explored. At times, the film's down-to-earthiness, its severe naturalism seems inadequate for capturing the immensity of the emotions.

But the characters' thinking and groping and sometimes cutting each other dead in real time offers a different kind of amazement. Where else do single shots of two people talking feel this full?

DAVIES: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine. You can download podcasts of our show at freshair.npr.org. Follow us on Twitter @nprfreshair, and on Tumblr at nprfreshair.tumblr.com.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.