'Pride And Prejudice' Meets 'Clue' At 'Pemberley'

Mystery writer P.D. James, now 91, has written a suspenseful sequel to Jane Austen's classic. Death Comes to Pemberley picks up six years after Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy have wed. Maureen Corrigan says the story is "a glorious plum pudding of a whodunit."

Contributor

Related Topic

Other segments from the episode on November 29, 2011

Transcript

November 29, 2011

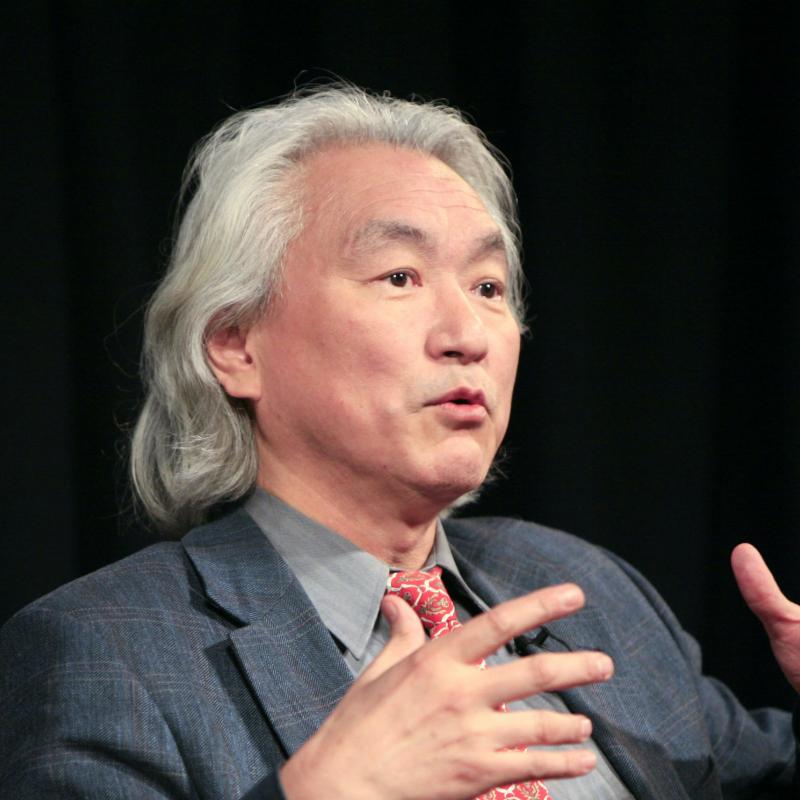

Guest: Tim Arango- Michio Kaku

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Tim Arango, is the New York Times Baghdad bureau chief. He used to cover media for the Times. In fact, you may have seen him in the documentary "Page One," about the Times media desk.

All U.S. troops will be pulled out of Iraq by the end of the year. This brings to a close a divisive chapter in American history. About 4,400 troops were killed in the war, and over $1 trillion were spent on it. But now comes a new chapter of uncertainty about the future of Iraq, the insurgency, ethnic divisions, Iraq's position in the region, and its relationship to the U.S.

I spoke with Tim Arango yesterday, as his brief stay in the U.S. was coming to a close. Tim Arango, welcome to FRESH AIR. America is leaving behind less of a presence in Iraq than was originally planned for a couple of reasons. One is financial. We don't have the money for what was originally planned. But the other is the Iraqis refuse to give American troops legal protection. Americans wanted protection against being prosecuted in Iraq. Why was that such an important issue for America, and why did Iraq refuse to say yes?

TIM ARANGO: Yeah, the interesting thing about the fact that the troops are leaving - and, you know, I've been there this year since March, and I think the expectation on all sides was that they would be able to get a deal where some troops could stay after this year. And that of course didn't happen. And so we have them leaving at a time when just about everybody involved in the discussion, from the American military leaders to the Iraqi military leaders, did not think it was a good idea that all the troops leave, that Iraq is not ready for that.

But there was always this issue in the background, which was immunity. And on the American side, it's a very fundamental and standard issue. We don't put troops anywhere in the world, whether it be Korea or Germany or any other places, where they would be subject to local laws.

TIM ARANGO, NEW YORK TIMES: And in Iraq it was this issue that they never dealt with over the summer, and then it finally came to a head in the fall. And I think for Iraq it was â it was this tortured legacy of the American involvement and, you know, issues from Abu Ghraib to the shooting by Blackwater in Nisour Square to the incident in Haditha and Anbar Province, and those issues where American troops acted badly and acted tragically and resulted in the deaths of Iraqis. And that legacy just came back to haunt this process, and the Iraqis said no way.

ARANGO: And it was an easy issue for politicians to demagogue on, particularly those that were opposed to the American involvement all along, particularly those Iraqis that are loyal to Muqtada al-Sadr.

GROSS: So would that immunity have extended to American contractors in Iraq?

ARANGO: No. The issue of immunity for contractors in Iraq, they stopped having immunity in 2009. So that was never an issue. It was basically an issue for American troops, and not that they would be immune from a prosecution but that they would essentially be immune from Iraqi prosecution. If an American soldier over there commits a crime, the American government is supposed to prosecute them here.

GROSS: Do you think that the future of Iraq is in some ways even more important now because of the Arab Spring and the instability in the Arab world?

ARANGO: I absolutely do because the whole old order, the whole American-backed order of supporting people like Mubarak, has crumbled. And for the United States to maintain influence there, they need an ally in Iraq, and it's unclear going forward if they will have that ally. And it certainly is incredibly important.

And people tend to look at Iraq sort of as its own particular, unique case right now. They don't look at it in the context of the Arab Spring. But you see Iraq, they've had elections, you know, before Tunisia and before Egypt, and it's still unclear if they're going to become a stable democracy. So in some ways it's still a test case as to if, you know, democracy can flourish in this part of the world.

GROSS: So we're leaving Iraq, and Iraq might not even be our ally after we pull out?

ARANGO: For the time being, they are. You know, while the troops are leaving, we are still going to have our biggest diplomatic presence since - the way it's described, the biggest diplomatic mission since the Marshall Plan.

There's going to be 16,000 diplomatic personnel, whether they be diplomats from the Foreign Service or contractors. And so there's a very ambitious plan to maintain influence there. But the problem will be that they will rarely be able to get around and travel around the country and see how the country is doing and interact with ordinary Iraqis.

And I think as time goes on, we're going to see, and one of the stories I - you know, is going to be, how hard it is for the State Department to maintain that influence in that environment when they can't move around and interact with the local population.

GROSS: So America's going to be leaving behind much less of a presence than was originally planned. Can you compare for us some of the things that were planned to remain behind when the American troops pulled out, compare that with what's actually going to happen?

ARANGO: Sure. On the military side, those are the big duties that the Americans will not be able to perform, things like intelligence gathering to the degree that they were going to do training of the Iraqi military. There's still a lot of deficiencies in the Iraqi security forces and the American military.

It was envisioned that they would still play a robust role in training them. Other issues that were potentially on the table were mediating disputes in the north, particularly around Kirkuk, which is the city that's disputed by Arabs and Kurds and Turkmen and is a potential flashpoint for violence after the Americans leave, issues such as patrolling the air, issues such as securing the borders.

Many, many things that the Americans had been doing they will not be able to do. And then a final one is counterterrorism. I believe to this day they still go out and do night raids with the Iraq special forces on suspected terrorists, and that will cease.

And there was a very robust partnership between the American special forces and the Iraqi special forces, and the Iraqis, while they were in the lead on the missions, they really still, you know, up until this summer and even to this day relied on the Americans for helicopters, for example, to get to target.

So there will be many, many things in terms of securing Iraq that will not be able to be performed after they leave.

GROSS: When we started - when the American military started the counterinsurgency campaign in Iraq, part of the method was to basically pay insurgents to go over to the American side. And this was called the Awakening movement.

And it seemed to be fairly successful in getting people to switch teams, but the question was always, okay, when you stop paying these guys, what happens then? So what has happened, do you know, to a lot of the men who had been in the Awakening movement and had been on the American payroll and are no longer?

ARANGO: Yeah, the Awakening has been an interesting story for the last couple of years, particularly there was this hope among the - these are obviously Sunni fighters, former al-Qaeda fighters, formal tribal fighters, particularly in Anbar Province and other Sunni areas. And there had been this hope that they were going to be able to transform that movement into political power, but that did not happen after last year's elections.

There's been a lot of anxiety, a lot of uncertainty among the Awakening because the Iraqi government has not lived up to their promises to integrate them into either the Iraqi security forces or into other jobs. So there's a lot of disenchanted former Sunni insurgents out there.

And then on top of that, they're constantly getting assassinated. Almost every week there's a number of assassinations of former Awakening leaders, and so they feel very disenfranchised and disillusioned. And so the risk is if you continue to alienate those people, you sort of have a ready group of people willing to rejoin the insurgency.

GROSS: There's still a lot of attacks in Iraq. Are the attacks still coming from insurgents?

ARANGO: Yeah, absolutely. If - the rule of thumb is if there's an attack on Iraqi civilians in the form of a car bomb or a suicide bomb, it's generally al-Qaeda in Iraq or one of the other insurgent Sunni groups. And those are the ones that still cause a lot of bloodshed.

Aside from that, there's another level of violence, which comes in the form of assassinations, frequent assassinations, mainly in Baghdad against ministers, judges, academics, and those are generally regarded to be carried out on behalf of militias loyal to some of the politicians.

And then the third level is the Shiite groups, which throughout this year have continued to attack American troops, usually with rockets and mortars against, you know, United States bases. And so the question with those folks is, who will they attack when the American troops leave? So it's still a many-layered and complex insurgency.

GROSS: So it's still not safe to serve in the Iraqi government. It's still not safe to be an Iraqi journalist and report what's going on, because those two groups are still subject to assassination threats and actual assassination.

ARANGO: Absolutely. A very prominent Iraqi journalist was murdered earlier this year named Hadi al-Madi, and I did a piece on him. He was a radio personality and one of these - he'd been an Iraqi who had been in exile and came back after 2003 with the hopes of contributing to this architecture of ideas and the language of freedom. And he was - you know, he was murdered earlier this year.

And he played a big part in sort of a burgeoning protest movement in Iraq, which did not pick up steam like in the other countries in the region.

GROSS: Now you say that there's a lot of threats by text. Like you get a text message warning you that you're, you know, you're going to be killed. Have you gotten any like that?

ARANGO: Now, but it's such a common experience among Iraqi journalists or anybody who has a role in public life who dares to speak their mind or say something that somebody objects to. It's just a universally common experience. And it's funny, I have an Iraqi cell phone, and every now and then I'll get a text, and it'll be Arabic.

And I'll run down to the newsroom, and I'll show it to one of my Iraqi colleagues, and I'll say: What does this say? Is this saying I'm going to be killed tomorrow? And it's usually always something from the cell phone company or a spam text.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Now let's keep it that way.

ARANGO: Yeah.

GROSS: So if you get a threat by text, if one gets a threat by text, is it easier to trace who sent it, or are people using, like, disposable phones?

ARANGO: No, they generally use throwaway phones. And it's gotten to the point where Iraqi journalists and others, they're so used to it that they almost, you know, disregard it.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Arango, he is the Baghdad bureau chief for the New York Times. He was formerly at the media desk and was one of the people featured in the documentary about the media desk called "Page One." Let's take a short break, and then we'll talk some more about Iraq. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Arango, the New York Times Baghdad bureau chief. You recently paid a visit to someone who was in a very famous photo that was taken in 2005. The photo was taken by Chris Hondros, one of the two photojournalists who was killed in Libya in April, in Misrata, While reporting on the uprising in Libya.

So the photo, the famous photo in question that Chris Hondros took in 2005, was after an Iraqi family drove through an American - drove through a checkpoint, and American soldiers fired on the car. The two parents were killed. There were five children in the backseat.

And the photo is of a five-year-old girl with her arms held out. Her mouth is open. She's clearly either screaming or crying. There's blood pouring down her cheek, and it looks like she's crying tears of blood. Her hands are all bloodied, and there's like drops of blood surrounding her.

Next to - oh, and the blood just perfectly matches the roses on her dress. And standing next to her in the shadows you see a soldier with a gun pointed toward the ground. What you did is you decided to track her down and see what's become of her six years later.

And when you tracked her down, you found out that she had never seen the photo. So you were the first person to show her this photo, which in some circles is a very famous photo about the damage of this war, you know, the civilians who have been killed, the children who have been killed.

So what did you think you were taking on, emotionally, when you showed it to her? And what was your reaction when you did?

ARANGO: I was not prepared for that, to be honest. I was sitting there in her living room, and it was her and myself and our photographer and one of my Iraqi colleagues, who was helping translate. And it was us sitting there with her and her guardian, which happens to be her brother-in-law.

We realized that she hadn't seen it, and they said they had never seen it. They said they had vaguely heard of this famous photograph that she was in, but they had never tried to find it or see it.

And they asked if they could see it. And I felt very uncomfortable at that moment. I was like, what should I do? And I had my translator very deliberately explain to them that this can be traumatic, are you sure you want to see it, are you sure you want to see it?

And they said they wanted to see it. And so immediately there I said OK. And so we pulled it up and showed them. And I still don't know if it was the right thing to do at the time, but it is what we did. And it was quite emotional for her to see it, but her reaction was more muted than you would think.

And I don't know if that's just a function of all the trauma that they've been through, and that a photograph, after everything they've seen, is, you know, not what we think of it as. And she became very loquacious after that. She had been very guarded before that, and then I guess emotions came flooding out, and she became very talkative and very interested in speaking about that and what she's been through. And I still don't know if it was the right thing to do, but that was what we did.

GROSS: Do you think the photo might change her life? Do you have any idea? Seeing the photo?

ARANGO: I don't think so, to be honest with you. I feel like all the trauma that they had been through - I mean, that wasn't the only thing. After that, her brother was sent to the U.S. for treatment, and he came back, and people thought that they were close to the Americans because the brother had been in the U.S.

They became a target of insurgents, and they blew up her house.

GROSS: Oh no.

ARANGO: And her brother was killed. So that wasn't the only moment for her that we saw in the photograph. And I don't know what that does to people over a long period of time. She's been taken out of school. She's been on medication. The way it could change her life, and this is what I've gone to in my head, is the number of people who came forward and sent me emails who wanted to help her, and maybe that will lead to something.

And I'm still trying to, you know, direct people to the right way without being a - taking a big role myself in that. But a number of people came forward and wanted to provide assistance.

GROSS: OK, so Americans helped her brother and flew him to the United States for medical treatment, to save him and then help him recover, and their home was blown up, and he was killed because of that help. Is it still the same now? If she got American help, would that make her a target? Or is it safer to get American help now?

ARANGO: It's safer now. It's not safe. I mean, that's the thing about Iraq in every way you look at it. It's safer, but not safe. And there's still that worry that any relationship to the Americans makes you a target, and you see that throughout all facets of Iraqi society, including the many people who have worked for the military over the years that are out of jobs. They're very nervous, as well.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Arango, the New York Times Baghdad bureau chief. So you used to be on the media desk at the New York Times. How did you get from media desk to Baghdad?

ARANGO: I raised my hand, basically.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

ARANGO: It was the summer of 2009, and there was a transition going on in the Baghdad bureau, and people were leaving. Some people were going to the Kabul bureau. And they needed new people to go and, you know, and work in the bureau and cover Iraq.

And it was something I always wanted to do, and that was why I always wanted to work for the New York Times, in the sense that it's a place where you can have a long and varied career covering many different things. And I always wanted to go abroad and cover a conflict.

GROSS: Why?

ARANGO: That's a very good question. I think it's a bit of a sense of adventure. It's a bit of sense of doing something substantial and something that gives you a certain satisfaction of being engaged in the big issues of the world. That's basically what it is, and I just sort of had that urging to go off into the world and do something different.

GROSS: Meanwhile, while you were in Baghdad reporting on Iraq, the News Corps phone-hacking story broke, and you'd covered News Corps when you were at the media desk of the Times. And there were several stories in the past few months where your name appeared with others on the byline, stories about News Corps and the scandal. So were you continuing to cover it from Iraq, or were you just, like, feeding information that you already had from previous reporting you'd done?

ARANGO: Yeah, it was funny because I'd covered the Murdochs for years, and even before the Times, I had been at the New York Post, covering the media. And so if you cover media at the New York Post, you get to know Rupert in a certain sense, and you get to know the Murdoch family. And so I had those relationships.

And so I brought them with me to the Times, and I covered that, and right before I left in March, I had done a long, long profile of James Murdoch. And so when the story broke initially, they asked me to reach out to a few people I knew. And so I would, and I'd send some feeds.

But then one day I got a call. It was about 7 o'clock at night in Baghdad, which was like noon in New York. And I was about to have dinner, and they said actually, we need you to write a front page story tomorrow on James Murdoch and what the scandal means for him and succession.

And after initially panicking a little bit, I just, you know, I stayed up all night and did it. And it was lucky because I had those relationships, and I could call on them. And I also had done a lot of reporting - a profile of James Murdoch that I did right before I left. And so I could draw on some of that and the people I had met.

I had gone to London, and, you know, somehow I put it together. But it was funny to be covering that from there. And I - you know, it would have even funnier if they had put a Baghdad dateline on it, but they didn't.

GROSS: So today's your last day at home and that you're making another stop in the United States for a story that you're working on. And then it's off again to Baghdad. At this point, when you're on the verge of returning to Baghdad, what are your feelings about going back? Looking forward to it, anxiety?

ARANGO: A little of both. The hardest part is the comings and the goings. It's when you leave, it's saying goodbye to, you know, your family and your friends and your dog. And then when you get there, it takes a couple days to get connected to the story again.

And then when you come back, it takes a few days when you get back to get Iraq out of your head. But after, you know, a short period of time, it's like when you're here, I don't think about Iraq, and when I'm in Iraq, you know, you don't think as much about here.

But you have to get yourself in that headspace, particularly, like, right now I'm in Vermont, and I drove to the studio, and it's just normal. When you're over there, you're in, like, a couple cars. You have armed guards. You're always sort of on edge a little bit wherever you're going because, you know, there is always that risk of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and you're always - it's trying to turn off the voices in your head when you're there and just sort of let go a bit and turn it over because you have to do your job, and you can't always be thinking about what's in this car's trunk, or what is under this guy's shirt.

Do you know what I mean? It's trying to get to a point where you can just do your job and let go of those thoughts, and it's hard.

GROSS: Well, thank you for your reporting. I wish you safe travels and safe reporting. And be well. I really appreciate your doing this interview during your limited stay in the United States. Thank you.

ARANGO: Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: Tim Arango is the Baghdad bureau chief for the New York Times. We recorded our interview yesterday. You can see the photo we were talking about, taken by Chris Hondros, on our website, freshair.npr.org, where you'll also find links to Tim Arango's recent articles. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. In the future, computers may be able to interface with your mind, cars may drive themselves, scientists may be able to grow new kidneys and other organs.

My guest Michio Kaku has written a new book about scientific innovations in the works, based on rapid advances in computers, biotechnology and artificial intelligence. It's called "Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100." Kaku is a quantum physicist who describes his work as grappling with the equations that govern the subatomic particles at which the universe is created. He co-founded string field theory. He's a professor of theoretical physics at the City University of New York. One of his previous books, "Physics of the Impossible,: was the basis of a Science Channel TV show "Sci-fi Science: Physics of the Impossible." Michio Kaku, welcome to FRESH AIR. Let's look at some of the inventions you think might be ready for use within the next 30 years. Why don't we start with Internet contact lenses.

MICHIO KAKU: That's right. The rate at which we are miniaturizing the Internet, it'll be inside our contact lens. So you blink and you go online. If you talk to somebody you'll see their biography appear right next to their name. And if they speak Chinese to you, you'll see instantaneous translation of Chinese into English. Now, of course, the first people to buy these contact lenses will be college students studying for final examinations. They will simply blink and see all the exam questions right in their contact lens.

KAKU: The next people to buy these things would be people looking for job.

GROSS: Wait, wait, wait. Won't they see all the answers too...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

KAKU: Well...

GROSS: ...if these contact lenses are so great?

KAKU: Yes. I'm a professor and it means that we have to change the way we grill our students. No longer will long strips of memorization, but concepts and principles have to be stressed. And people who are looking for a job will also buy these contact lens. In a cocktail party, you will know exactly who to suck up to at any cocktail party. You'll have a complete read-out of who they are. And actors and actresses - they'll never flub a line. They'll simply see all their lines right inside their contacts lens. Now, these things already exist in some form. I work for Discovery Channel, the science channel sometimes, hosting the documentaries, and I took a film crew down to Fort Benning, Georgia to look at the military's version of these Internet lenses. You place it on your helmet - it's a tiny lens - you flip it down, and immediately you see the Internet of the battlefield. Enemy forces, friendly forces, artillery, armor, aircraft, all of it right inside your eyeball.

GROSS: How can you extrapolate everything that you did from what the military is using now? You know, that actors will use it to...

KAKU: Well, I'm not...

GROSS: ...to act and will go to a cocktail party and see everybody's biography when we meet them.

KAKU: Well, I'm a physicist, and we have something called Moore's Law, which says a computer power doubles every 18 months. So every Christmas, we more or less assume that our toys and appliances are more or less twice as powerful as the previous Christmas. For example, your cellphone has more computer power than all of NASA when they put two men on the moon in 1969. And a birthday card that sings Happy Birthday to you - that birthday card has a chip in it with more computer power than all the Allied Forces of 1945. Hitler, Stalin, Churchill would have killed to get that chip that you simply throw away in the garbage. Because of Moore's Law, we physicists can project 10, 15 years into the future with near mathematical precision.

And prototypes have already been made of Internet glasses, Internet lenses, and also even a prototype of an Internet contact lens. And so, eventually, everyone will have it and we will live in what is called augmented reality. And so, this will be part of life. Everything we see around us will be annotated, footnoted and we'll love it.

GROSS: You sure of that?

KAKU: I'm sure, because how many times have we bumped into somebody and we say, who is this person? Jim, John, Jay, I know this person. In the future, you will know exactly who you are talking to and if you see an object you don't understand you'll immediately understand what that object is, and this is going to have a revolutionary effect.

GROSS: One of the things you write about is how our minds, our brains might in the future be able to interface with artificial intelligence. I guess I have no idea how that would work.

KAKU: Well, on several levels. Already at Brown University they've taken stroke victims and put a chip in their brains and connected the chip to a laptop computer. And these individuals who are paralyzed can now read e-mail, write e-mail, surf the Web, play video games, guide wheelchairs. Anything you can do on a computer they can do as well, except they're trapped inside a paralyzed body. And we can also use this to control robotic arms.

GROSS: Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. Let's back up.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So they're having a thought like move this chair or type this letter. How does that thought get translated into the computer?

KAKU: What they do is they simply attach a chip into the brain and then you are allowed to look on a computer screen where the cursor is located. Then it's like riding a bicycle. Painfully you have to learn that certain thoughts control the movement of the cursor - moving it left, right, up and down. It takes awhile - it takes a few hours. But after a while by looking at the cursor, you realize that certain thoughts will move the cursor in certain directions. And after a while, you can simply move the cursor in any way to do, for example, crossword puzzles or to play video games. But it does take a while because the architecture of the brain is still not mapped out yet. That'll take many more decades before we have a roadmap neuron for neuron, and can attach these things directly.

GROSS: What you are describing sounds like a really painstaking process. Like if you wanted...

KAKU: It takes a few hours, but after that somebody who is totally paralyzed, cannot communicate with their loved ones, cannot do anything except vegetate, all of a sudden can control objects around them, write e-mail, surf the Web, anything you can do on the Internet, they can also do. And previously they were trapped. And in animals, for example, we've even taken it one step further. Monkeys have been connected at Duke University to robotic arms, so they control robotic arms and can even grab bananas and eat bananas by controlling a mechanical arm that is connected to their brain.

Now in Japan, they've actually connected a robot called ASIMO - one of the world's most advanced robots in the world - to a worker who puts on a helmet and the worker then can actually control the upper body motions of ASIMO. And this could also be the future of the space program. It's very dangerous to put astronauts in the moon base where there's radiation, solar flares, micrometeorites. It'd be much better to put robots on the moon and have them mentally connected to astronauts on the Earth.

GROSS: So let me ask you, if you take the kind of focused mind that you're talking about and you take away all the technology and think about what the mind can do, does that make a powerful argument for meditation?

KAKU: Well, the mind is powerful if it focuses and reduces distractions and you can increase learning capabilities. But you will have to enhance it using radio and using computers, especially if you get into very complicated things like memory. However, two months ago, history was made with a mouse brain. They actually were able to input memory directly into a mouse. This is the first time in history it's been done. It's something right out of science fiction. What they did was they looked at the hippocampus of a mouse and tape-recorded impulses as it learned a task. That's the gateway for memory: All memories first go through the hippocampus. They tape-recorded the impulses. Then they gave it a chemical which made the mouse forget the task. Then they took this tape-recording - this set of impulses - shot it back into the mouse, and the mouse immediately knew how to do the task. So this is the first time it's been demonstrated that you can actually tape-record a memory and then reinsert the memory into a mouse and have the mouse perform the task that it previously forgot.

Now the implications of this are enormous, because of all memories goes through this hippocampus, this is also how our brain functions and it means that memories in principle - it hasn't been done, of course, but memories in principle might be tape-recorded and then shot right back into your brain or somebody else's brain. So that somebody, for example, can learn calculus without having to study too hard.

GROSS: Well, how do you recorded memory? What is - how do you measure a memory? Yeah.

KAKU: What they've done is since we do not really understand the architecture of the brain, reverse engineering is still science fiction. What they've done is they've simply taken the impulses, the impulses that go through this part of the brain which is the gateway, the gateway to memories. So all new memories have to go through this gateway and you can simply tape-record impulses as it goes through the gateway and then later reinsert the tape-recorded message. And in the coming decades, as we get better and better at it, we may actually be able to record whole sequences of memories, like vacations, for example.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Michio Kaku. He's a theoretical physicist, a co-founder of string field theory, and author of the new book "Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100." Let's take a short break here, then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Michio Kaku. He's a theoretical physicist, who is a co-founder of string field theory, and his new book is called "Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100."

Now when you were in high school - and you're kind of famous for this - you built a particle accelerator in your mother's garage. What is a particle accelerator?

KAKU: Well, it's an atom smasher. The biggest one in the world is much bigger than the one I built in high school. It's 17 miles in circumference and it creates a mini Big Bang to re-create the conditions of the early universe. What I did when I was 16 years old is I went to Westinghouse, I got 400 pounds of Transformers steel, 22 miles of copper wire and I assembled a six kilowatt, 2.3 mini electron volt of electron accelerator in the garage. When it was finished, I would plug it in. There was this huge crackling sound as I consumed six kilowatts of power. I blew out every circuit breaker in the house. All the lights were plunged in darkness. And my poor mom would come home every night, see the lights flicker and die and say to herself: Why couldn't I have a son who plays baseball? And for God's sake, why can't he find a nice Japanese girlfriend? What's wrong with him? Why does he build these machines in the garage? Well, I love to build machines. It got me into Harvard, so I can't complain, and that began my career as a physicist.

GROSS: So you ended up as a student being mentored by Edward Teller. Teller being known as the father of the hydrogen bomb. He worked on the Manhattan Project, which developed the atom bomb. When you started studying with him did you think about going into nuclear weapons development as a career?

KAKU: Well, he very strongly urged me to go into nuclear weapons design. I was in high school. I was playing with antimatter. Antimatter naturally occurs from a substance called sodium 22. I put antimatter in a magnetic field and photographed the tracks of antimatter. I went to the National Science Fair and I met Edward Teller. In fact, I was on television with Edward Teller. I didn't have to explain to Edward Teller what antimatter was. He immediately knew what it was. He immediately knew what I was doing and he offered me a scholarship to Harvard.

However, you know, he had an ulterior motive as well. Let's be very frank about this. There's a book written by a New York Times reporter called "Star Warriors," and it's about a scholarship that Edward Teller was promoting. I was a recipient of that scholarship. And later it came out that the purpose of the scholarship in part was to create a cadre core of young bright scientists to propel a Star Wars program. These are young physicists just like me, who fell under his wing and were shepherded into the weapons program.

And when I got my bachelors degree from Harvard he made a pitch. He made a very big pitch. I could go to Los Alamos, I could go to Livermore, I could go to MIT and study nuclear weapons design. Unfortunately for him, I decided that I wanted to work in things that were not so destructive but perhaps had even more power, and that is an explosion called the Big Bang, which was infinitely more powerful than a hydrogen bomb.

GROSS: You're Japanese and your father was born in Japan. Did the fact that atom bombs were used on the country of your father's birth affect your decision at all? I mean understanding...

KAKU: Well, my parents...

GROSS: ...like the destructive power of it and maybe knowing something about all the civilians who were killed?

KAKU: Well, my parents were actually born in California. However, they were sent back to Japan, which was very common for immigrant families, and they grew up in Japan. They were U.S. citizens, born in California but raised in Japan. And then they came back to California at the wrong time. They came back to California before Pearl Harbor and when Pearl Harbor hit there was all this hysteria. And my parents were then locked up and shipped out to a relocation camp, along with 110,000 other Japanese-Americans. And my parents were citizens, and yet they, too, were rounded up and sent off to the camp. They lived from 1942 to 1946 behind barbed wire and machine guns.

All civil liberties were stripped from them, and they spent the war years basically locked up behind barbed wire. Now, the fact that the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima had an impact on me, being Japanese-Americans. But I said to myself that maybe there's some good that can come out of this. Maybe science can liberate us from poverty, disease, oppression, ignorance.

And I firmly believe this. I believe that science is the engine of prosperity, that if you look around at the wealth of civilization today, it's the wealth that comes from science. And by being a scientist, I can be part of this grand search for knowledge which will liberate because this knowledge will create prosperity. And much of the problems of human society comes out of scarcity.

And I think that by creating a world of plenty, by creating institutions and organizations that promote knowledge and promote understanding, I think I could be part of being in a better world.

GROSS: Now, among your accomplishments is that you are a cofounder of String Field Theory. I'm going to ask you to explain what that is in the absolute simplest way possible...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: ...simplest and briefest way possible.

KAKU: Okay. Well, Einstein spent the last 30 years of his life chasing after a theory of everything, an equation perhaps no more than one inch long, that would allow him to, quote, "read the mind of God," one theory which would summarize all physical law into a single expression.

Well, today we think we have the theory. It's called string theory. Very controversial, but we're testing the periphery of it with huge machines like the one in Geneva, Switzerland, the Large Hadron Collider. Now, what I've done is I've taken all the equations of string theory, which fill up an entire volume, a gigantic book of equations, and I've summarized it into one equation, one inch long. That's my equation. It's called String Field Theory.

The language of physics is something called field theory. We have magnetic fields, gravitational fields, electric fields. That's the language of physics. But string theory was this hodgepodge of little equations and rules of thumb, and what I decided to do was create a field theory of strings, just like we have a field theory of magnetism, a field theory of electricity, a field theory of gravity. And that's what I did.

We can summarize electricity, magnetism and gravity into equations one inch long, and that's the power of field theory. And so I said to myself: I will create a field theory of strings. And when I did it one day, it was incredible, realizing that on a sheet of paper I can write down an equation which summarized almost all physical knowledge. That was power, the power of mathematics.

GROSS: If I asked you what the theory is, would I understand your answer?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

KAKU: Well, very simply, that all the sub-atomic particles - neutrons, protons, quarks - are nothing but musical notes on a tiny rubber band, that when you twang the rubber band, it changes from one frequency to another. So it changes from an electron to a neutrino. And you twang it enough, it can turn into all the subatomic particles we see in the world.

So all the subatomic particles that make up our body are nothing but different notes on many, many, many tiny little violin strings, little rubber bands, and that physics is nothing but the laws of harmony of these vibrating strings. Chemistry is nothing but the melodies you can play on these vibrating strings. The universe is a symphony of strings, and the mind of God that Einstein wrote eloquently about the last 30 years of his life, is cosmic music resonating through 11-dimensional hyperspace. That is the mind of God.

GROSS: How do you know you're right? How do you know the equation is correct?

KAKU: Well, no matter how beautiful the theory, one irritating fact can dismiss the entire formulism, so it has to be proven. So that's where we hope the Large Hadron Collider, the biggest machine that science ever built, will create what are called sparticles. Sparticles are super-particles. They are partners of ordinary particles. We're made out of the lowest octave of the string, but these little rubber bands have higher octaves - that is, new particles that have been seen yet.

They're called sparticles or super-particles for short, and we hope to create them with the Large Hadron Collider. It's still a bet. We physicists are taking bets as to whether or not the Large Hadron Collider is powerful enough to create sparticles, but if it does, that could change the whole landscape of modern physics.

GROSS: Sounds exciting.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

KAKU: Yeah, it's exciting.

GROSS: I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

KAKU: Oh, my pleasure.

GROSS: Michio Kaku is a professor of theoretical physics at the City University of New York. He co-founded String Field Theory. His new book is called "Physics of the Future." You can read an excerpt on our website: freshair.npr.org. Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews P.D. James' new mystery novel, which is James' sequel to Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice." This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: P.D. James pretty much epitomizes the term living legend among mystery writers. At 91, she's the author of 20 books. In recognition of her great contributions to mystery literature, James, who is from a middle-class background, was given the title "Baroness James of Holland Park" in 1991. Now James has decided to pay tribute to a writer whose works has stayed with her throughout her long life.

James' latest novel is called "Death Comes to Pemberley," and it's a sequel to Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice." Book critic Maureen Corrigan has a review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN, BYLINE: During the 50-plus years that Agatha Christie actively reigned as the queen of crime, it became something of a tradition in England to give one of her novels as a holiday present. In fact, she and her publishers popularized the slogan: A Christie for Christmas. Dame Agatha died in 1976, but the association of murder most foul and the yuletide season lingers.

This year, British mystery lovers in particular have a glorious plum pudding of a whodunit awaiting them. P.D. James has taken up the challenge of feeding readers' holiday hunger for homicide. What's even more tantalizing is the fact that James' latest mystery is also a tribute, of sorts, to one of her most cherished authors, Jane Austen. James' new novel is called "Death Comes to Pemberley." Think "Pride and Prejudice" meets "Clue."

To enjoy this mystery - which I did, enormously - you must take it on its own terms: "Death Comes to Pemberley" is a sequel to "Pride and Prejudice," written in the spirit of what Graham Greene famously called an entertainment. James is having fun in her own intelligent, literate way, and this novel is an invitation to her readers to join in the revels.

In so many ways, James and Austen are suspense sisters under the skin. Money, one of Austen's chief themes, certainly lies at the heart of many a crime in James' mysteries. Another commonality is that James' writing style has always had something of the 18th century about it: Think of all that formal, balanced poetry her detective, Adam Dalgliesh, cranks out.

Naturally, then, James is adept at spinning out those skewering epigrams that we associate with Austen. You'll recall the immortal first line of "Pride and Prejudice": It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. Well, James is much too wise to go toe to toe with Austen on that line, but she does produce some gentle Enlightenment zingers of her own.

Speaking of the odious Mr. Collins, the narrator here tells us that his canny wife, Charlotte consistently congratulated him on qualities he did not possess in the hope that, flattered by her praise and approval, he would acquire them.

There's something even more profound, however, that James brings to her reading of Austen. In "Death Comes to Pemberley," she ferrets out the alternative noir tales that lurk in the corners of "Pride and Prejudice," commonly thought of as Austen's sunniest novel. Ruinous matches, early deaths, the Napoleonic Wars, socially enforced female vulnerability: Austen keeps these shadows at bay, while James noses deep into them.

"Death Comes to Pemberley" takes place six years after Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy have wed. Lizzie has dutifully produced an heir and a spare, and seems, at first, to have lost her girlish sass and sparkle. But marriage does tend to drain life out of our intrepid literary heroines. Consider Jo March or Bella Swan.

On a dark and stormy night before the annual great ball at Pemberley, a carriage careens up the drive, and out stumbles Elizabeth's ne'er do well sister, Lydia, shrieking hysterically about her missing husband, Wickham. The men of the manor launch a search party and, later that night, in the middle of some blasted woods, Wickham is spotted, spattered with blood and bending over the body of...

But, I won't let the identity of that corpse out of the cupboard. As Austen did in her elegant spoof "Northanger Abbey," James clearly enjoys muddying her Wellies here in the Gothic literary terrain of ghosts and ancestral mansions and curses. Throughout the mystery that unfolds, she ingeniously works in characters and themes, great and small, from "Pride and Prejudice," and also gives erudite nods to the history of forensics and jury trials in Great Britain.

I cautioned earlier that "Death Comes to Pemberley" should be read in the spirit of an entertainment, but certainly even entertainments have the power to be moving. James has said in interviews that crime fiction and the novels of Jane Austen have been two of her life's abiding passions. To think of P.D. James, at age 91, so successfully uniting those passions between the covers of one book is a thought to warm a reader's heart in the dead of winter.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She reviewed "Death Comes to Pemberley" by P.D. James. You can read an excerpt on our website freshair.npr.org, where you can also download podcasts of our show.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.