Paying Tribute to War Photographers.

Photojournalists Horst Faas and Tim Page They've compiled and edited a book of photographs by photojournalists who lost their lives covering war in Indochina and Vietnam from the 50's to the mid 70's. The book is titled "Requiem" (Random House). It features 135 different photographers including Robert Capa, Larry Burrows, and Sean Flynn. Horst Faas was an Associated Press photographer in Vietnam and Tim Page worked in Laos and Vietnam for United Press International and "Paris-Match." They were both wounded in Vietnam.

Guests

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on November 5, 1997

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: NOVEMBER 05, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 110501np.217

Type: INTERVIEW

Head: Interview with Tim Page and Horst Faas

Sect: News; International

Time: 12:00

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

One-hundred-and-thirty-five photojournalists died or disappeared while covering the wars in Indochina, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. The new book "Requiem" is a memorial to them. It collects some of the extraordinary pictures they gave their lives for.

The book is edited by two photojournalists who were wounded in Vietnam, but survived: Tim Page and Horst Faas. Page is an English freelance photographer who first started taking pictures of war in Southeast Asia at the age of 18. He was wounded four times while covering the war in Vietnam. He's worked for wire services and magazines.

Horst Faas is a German photographer and editor with the Associated Press. He was the AP's chief photographer in Southeast Asia from 1962 to '74. He's won two Pulitzer Prizes. He's now AP's senior editor in London.

Horst and Faas knew many of the photographers represented in their book, "Requiem." I asked what impact it had on them when a colleague was killed while taking pictures. Tim answered first.

TIM PAGE, PHOTOJOURNALIST AND CO-EDITOR OF "REQUIEM": I think probably in Vietnam we became a little inured, in a certain sense. And we went on -- surfed over the trauma of it, the emotion of it, because should you let that trauma, emotion dominate your existence, then it would be damnably difficult to go back out in the field and do -- to make more pictures. Now, you didn't make light of it. You became very sad and very -- reminisced about the person -- but had make light of it or else you could not re -- go out and function again.

GROSS: How would you make light of it?

PAGE: How would you make light of it? You would josh about the person, I suppose. You would try to remember the more, you know, if you say, pornographic or slightly obtuse moments that you'd been in a place with the person. You would remember his images -- her images. You make light of something -- you stop just being sad about it, or else you -- if every death, should every death you see out there, you would have just stopped and left.

GROSS: Horst Faas, did you find that when you had a friend or a colleague who was killed in Vietnam -- a photojournalist who was killed -- would it make you any more or less cautious in your own work?

HORST FAAS, PHOTOJOURNALIST AND CO-EDITOR OF "REQUIEM": Oh, I was -- I was trying to be cautious from day one. I had covered other wars before and I knew it was dangerous. As an agency -- agency reporter and head of the photo operation of an agency as AP these days, the death of somebody always for a very brief -- I would stop all the activity. I mean, people talk to each other and they talked immediately about this person, and nothing much happened in the AP bureau. But since times grows really very short, and then everybody try to get back to work almost more determinedly than before; for the photo editor himself was possibly the one who sent the killed colleague out on the assignment.

There was a lot to do. The body had to be brought home. The family had to be informed and talked to. We attended funerals in the beginning. And we tried to bury the -- bury the mourning somehow under activity. Do you understand?

GROSS: But now wasn't that sometimes your responsibility? Weren't you often the assigning editor who had to take care of it?

FAAS: I -- it was my responsibility to deal with headquarters -- explain to headquarters what had happened and then talk to the family; talk to the wives or talk to parents and explain what happened, and go out myself to the place where a person was killed and see for myself what happened. I remember going out and trying to find one of our American photographers, Ollie Noone (ph), who had crashed -- had been shot down in a helicopter; and took three, four days of walking with troops and troops that were under continuous attack until we reached the helicopter. I found the camera which had been thrown clear, and the film inside was still intact. But there was almost nothing left of Ollie Noone (ph).

So I watched the people that deal with corpses and remains -- watched them sorting out the scene. I kept the camera and went back to Saigon and had the difficult task to explain what happened to the parents and the sisters.

GROSS: What did you say? Do you remember?

FAAS: No, I think that was very, very private. I think -- I think we try to be honest at the time. We try to be not -- we tried not to use the normal -- the normal words of mourning -- "and I'm very sorry" and so on -- "he was the greatest." No, we didn't do it. We tried to be very clinically exact -- what exactly -- what happened, how a person died, possibly saying that there was not much pain. There was just sudden death. And try to be honest, eh?

GROSS: Were you ever in a position where you had assigned a photographer to do someplace to take pictures and they were killed on that particular job?

FAAS: All the -- no assignment was an assignment where people were ordered to go to places. We generally assessed the day-to-day situation and then photographers would go out according to their preferences. I had Vietnamese would rather go out with Vietnamese troops. We had other Vietnamese photographers who loved the American Marines.

If they did so, then let them go up there. They were all -- almost all equally good. There were no bad photographers around. There was nobody who was second -- second category. There's no room for mediocre talent in situations like this.

GROSS: Did you ever try to talk an AP photographer out of going to a certain place?

FAAS: Oh, yes, many times. I mean, I myself -- I myself spent about 50 percent of my working life in Vietnam in the field. That means I would go out for five days and then stay in Saigon for five days and play the editor for the others, and then go out myself again and leave another photographer in -- at the editing desk. We took turns. So we all had -- we all had our experiences there.

I, being a little bit on the senior side already -- in these days, I was 30 and older so -- but older than many of the young colleagues, including my friend Page. I tried to warn people. I tried to instill to them that they shouldn't go with bad troops. They should rather pull back and take care of themselves and look out for photos when situations became dicey and never ever be foolishly risking -- risking chances.

GROSS: What are "bad troops"?

FAAS: Bad troops are the troops that don't take care of themselves -- Marines that don't dig in; patrols that don't put out points; companies that go through the jungle in single-file without having flanks out; troops that handle their weapons sloppishly (ph); artillery observers that don't check out the town properly; and so on.

GROSS: Did you find that when you traveled with troops that they looked after you? Or that -- did they see you as a burden -- you know, someone who's not a member of the military who's tagging along?

FAAS: That was one of the main, main features of a good combat correspondent, combat photographer, not to be a burden to the troops. It started was being equipped and dressed and -- like soldiers. It means you had to have the right boots and you have to have your own overnight gear and you have to carry your own food. The only thing you don't carry is your weapon. You had to protect yourself with a steel helmet and a flak jacket just like they did.

And when there was danger, you could not count on them putting a shield around you and defending you. No, you had to just run with them and hope for the best. But it was not our role ever to participate in the fighting.

On the other side, among the communist photographers, that was their prime role. They were soldiers foremost and reporters, propagandists -- photographers secondary.

GROSS: When you were photographing combat, what kind of rules of thumb could you use to know when to take pictures and when to just run for cover?

PAGE: I think it's a cross purpose. You learn where you can -- it's -- it's a sixth or seventh nature. You learn where you can take pictures from and be safe simultaneously. You learn how to move, where to position yourself. You learn how to shoot on the run, and this was the advantage of today's all-thinking and seeing camera and autofocus. You learn to anticipate. You learn to try to sort of preempt what's going to go on and where you can place yourself.

It becomes -- it becomes a sixth or seventh sense in the end. You just automatically know where -- you know that a rubber tree won't a bullet, so you don't hide behind the rubber tree. Admittedly, the opposition can't see you behind the rubber tree, but stray weaponry will come through that rubber tree.

GROSS: What were the editorial standards of the newspapers and magazines you were working for in terms of how explicit you could -- your photographers could show death and dying -- the carnage of war?

PAGE: Life magazine at that time, I think, who I was doing a lot of work for, were consistently running images. I mean, not just my images, but I mean, Larry's images and other very good photographers' images, which were as close to the edge as you can get. There were -- I mean, there were pictures of people actually being killed for -- I mean, I'm not saying like the Capa's image in Spain and the Spanish Civil War -- but there were pictures. I mean, Larry Burrows spread of Yankee Papa 13. There were -- and not -- the images in there where people did die.

I think the contentious area is where those were -- you had American or South Vietnamese troops interrogating and torturing suspects. And these always were kind of borderline issues. And the issue which was always kept to the fore of our minds, which was mainly Horst's concern, was not to release pictures into the media stream on the wire or have them printed in magazines before next-of-kin of those who had been killed or seriously wounded were released and before the next-of-kin were actually notified.

So that was -- but that was almost like self-censorship in the sense that it was to protect. I mean, not to protect, but to make sure the next-of-kin -- the first thing, they didn't know about the death of their son or father or whatever -- husband -- before officialdom got to them, they didn't see it splattered across the front page of the local newspaper. That was just a thing for the feelings of the next-of-kin.

GROSS: My guests are photojournalists Tim Page and Horst Faas. Their new book "Requiem" is a collection of photos taken by photojournalists who died in the war in Vietnam.

More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

BREAK

Back with photojournalists Tim Page and Horst Faas. Their new book "Requiem" is a collection of photos taken by photojournalists who died covering the war in Vietnam. Both Page and Faas were wounded while covering the war.

David Halberstam wrote a piece in Vanity Fair in which he talked about you, Horst Faas, and he described you as one of the first photographers in Vietnam to use a Leica, which enabled the photographer to look forward instead of down. Would you describe what that difference was and how that affected your safety and your photographs?

FAAS: Well, I wasn't the first one to use Leicas. Larry Burrows arrived at almost at the same time, had considerably more Leicas than I had because at the time AP was still working with large (ph) cameras and I carried one or two with my own Leicas in there.

Well, a Leica camera is a camera we can keep both eyes open. You can look with the free eye that doesn't look sort of (unintelligible) all directions. It's like backwards -- and sometimes also backwards. And you can look through the viewfinder and see your picture.

So it may be sports photography or it may be war photography, the Leica camera appeared to me a camera that made it possible that you were at all times aware of things happening around you.

GROSS: Jim Page, did you use that, too?

PAGE: Initially, nay. After I'd made my first -- had my first spread in Life magazine in mid-'65, almost the first thing I did with all this new-found wealth was buy two Leicas in Hong Kong. But it has to be said that almost the first foreign -- one of the first foreign photojournalists to be killed in Indochina, Robert Capa -- I mean, of World War II fame and Spanish Civil War fame -- also used Leicas. I mean, they have been the -- the camera of choice for war photography since -- I mean, they were used by the Germans in the Second World War. I mean, (unintelligible) magazine consistently had photographers using Leicas and Contaxes.

I mean, the Contax looks much like the Leica -- much -- similar technology in lenses. But it's always been the strongest -- it's kind of the Rolex of the cameras -- the Rolex cum Volkswagen.

FAAS: The other wonderful thing with the Leica was that you could actually take it apart like a rifle, clean it out, dry it out, put it together again with a set of little screwdrivers. And it would work again -- something that is impossible with today's electronic chip cameras.

GROSS: Drying it out when you're in the middle of the jungle was probably a good -- good thing to do.

FAAS: No, it happened very often that you fell into a water hole on the river and ...

PAGE: Bomb craters.

FAAS: ... you couldn't -- you couldn't operate any more. Your whole being there was useless. And at that time, the troops will take a little break. You'd take your cameras apart and put it on a black piece of plastic and hope the sun comes out and dries your cameras out. If not, they go back in a plastic bag and you wait until the next stop and then spread them out again.

So sometimes it took a day or two or three to get the stuff working again, and then you were back in operation.

GROSS: Well, I can imagine how you must have felt, though, when your camera wasn't operating and you're caught in combat and wondering, or at least I'd be wondering: What am I doing here?

FAAS: That's right. Yeah.

PAGE: You spend most of your time saying that anyway.

FAAS: I could, of course, become a word reporter that goes for nights. When you're out in a military situation, you can't take pictures at night with flash lights. So at night and in bad weather and dark weather, the cameras went back into the fish-tackling boxes, which was waterproof and I would just use my mind and try to keep quotes there and write down little stories. And many a times, I came back without photos, but there's a good memory of a good tale; and would sit down at the typewriter and write my story for the AP.

GROSS: Horst Faas, earlier we were talking about your responsibility as an editor at the AP, dealing with a photojournalist's death -- calling the family, dealing with the remains of the body. I'm wondering, when a reporter who worked with you at the AP died what it was like for you to develop their last roles of film, if you were able to find film on their bodies or in their cameras after their death?

FAAS: Well, that's very difficult to say. I mean, of course you hope that there is something on this camera that would be worthwhile to be sent out and be a last testimony to a man's talent. This whole book is a little bit like that. We try to not revive their name -- the memory of their names and the memories of their birthplaces and their background. What we tried to do is we remind of the great talent that was lost out there -- talent that wrote a very important chapter in the history of photojournalism in this century.

So when a man died, we looked back at his work and we tried to assess what he had achieved and what he had done in his life time. The last role of film was simply like the last paragraph of a story.

Of course, it's sad and of course it's -- everybody comes and looks at it and tries to understand what happened. There's a picture of a young Indian who traveled via Singapore who desperately wanted to be a reporter/photographer with the AP. He lived only 14 days.

When he was on his last military mission, he was up front at the point of a company on a patrol and a mine blasted into the company. He didn't have the experience to know that one mine seldom comes alone, so he stood up and photographed American medics helping dying soldiers. And while he took his last six, seven, eight pictures, a second mine exploded and cut him down -- standing up at the time taking these pictures.

So I remember very well his last roll of 18 negatives, and the last picture shows clearly that he stood and that he took a picture that he was -- he went out there to take -- combat, that is. The picture almost explained his death. These last 18 negatives, I remember, were sent on orders from headquarters to the then-general manager/president of the AP with a very -- with a very detailed explanation how Charlie Chilapa died. Our president wanted to know how it happened again that an AP man died; what could we do better to prevent the repetition of this?

Well, there was no answer to my report because nothing was done wrong except that the man shouldn't have stood up after a first mine. So he had -- the last pictures were telling the tale and as it happens, they are about the only pictures that I remembered of Charlie Chilapa, one of which is published -- his last picture and date and published in our book, together with my slightly apologetic message to President Ross Gallagher (ph), why Charlie Chilapa died.

GROSS: Horst Faas and Tim Page edited the new book Requiem which collects the work of photojournalists who were killed while covering the war in Vietnam. They'll be back in the second half of our show.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

BREAK

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with photojournalists Tim Page and Horst Faas. Their new book "Requiem" is a collection of pictures taken by photojournalists who died covering the war in Vietnam.

Tim Page is a freelance photographer. Horst Faas is the Associated Press' senior editor in London and was their chief photographer in Southeast Asia during the war. Page and Faas were both wounded while covering the war.

Well, Tim Page, I believe that you were injured and returned to combat more times than any other photojournalist in Vietnam.

PAGE: I was hit four times, in one train wreck, and one motorcycle wreck, and one car wreck. After three woundings -- two of them relatively minor -- I mean, in combat or out in the field -- the third time was very serious when the American Coast Guard cutter shot up by American planes. I got 400 pieces of shrapnel in my body.

At that point, Time-Life paid for me to leave the country, and I immediate -- I was reassigned -- I was given a contract to work out of the Paris office and cover the Six Day War and other conflicts in the west. But I had to go back in '68 after the -- during the Tet offensive, just after the Tet offensive. I couldn't stand there and watch the Tet offensive go on, as it were, live on television and seeing the pictures in Life magazine or -- and all my buddies and friends' pictures being used. And I'm sitting in Los Angeles (unintelligble) in neutral.

And I took a one-way ticket back to Vietnam, arriving just in time for the second Tet offensive, when the press corps lost about eight people in three days. And instantly, I arrive with 50 cents in my pocket, and within four days I had six pages in Life magazine.

It's -- it was something that was bigger than we were. I mean, speaking from the freelance point of view. It was the war to be in. And providing you went out enough and got to wars where it was hitting the fan, then you could guarantee getting decent spreads into magazines and sell your images, be it to AP or UPI or to one of the other agencies. Or you would have a commission from assignment to one of the major magazines.

And that's what you're being paid for, or you were trying to break into that world so you became a known photographer.

GROSS: You were wounded several times -- four or five times -- in Vietnam; kept going back for more. Did you ever feel like you were tempting fate? That you'd come so close that you should just stay away?

PAGE: Yeah, in '67, it got to that point. I mean, Sean Flynn, Errol Flynn's son and myself were sitting in a bunker, just inside the Demilitarized Zone -- the DMZ -- on the south side. And we'd gone in with some South Vietnamese airborne forces to retrieve bodies and wounded from -- when they'd been ambushed the night before. And we were caught by North Vietnamese artillery. And then by -- immediately after that, by friendly fire -- American Phantom bombers came in and strafed and bombed us.

And Sean and I ended up in a little tiny house -- a shelter underneath the house -- cowering, just terrified. We both made a pact we were going to get out of there very, very soon. And I got out within six weeks of that event and Sean left within a couple of months of that event.

GROSS: But Sean ended up dying in Vietnam. He was ...

PAGE: No, he was captured. The whole of this book, and the memorial process -- remember, this process started back in 1979, so it -- 1989 -- when I went to Cambodia to unearth or to try to discover the fate of what had happened to Dana Stone (ph) and Sean Flynn -- two photographers. Sean was working at the time for Time and Dana (ph) was working for CBS.

And they were captured by North Vietnamese cum Viet Cong reconnaissance troops, very close to the South Vietnamese border in Cambodia. And were given, after that point, to Khmer Rouge about four or five months later, and were held for something just over a year, and were finally executed. And a French student who was doing his research on journalism in Southeast Asia managed through the Freedom of Information Act to get details about their demise -- these declassified documents from the CIA and DIA -- and sent me copies of these things.

And I tried to get as close to the site as possible where they had been executed and held. And at that point, I decided I was going to try to build a memorial to all the media who had been killed or wounded or missing in Indochina from all sides, not just, as you say, from the West, but from the Vietnamese side -- North Vietnamese, Viet Cong side, liberation front.

GROSS: Tim, what was the last wound that you got in Vietnam and why did you stay...

PAGE: I didn't stay. I mean, on the last wound, I took a piece of shrapnel in my brain, and they took out of my brain 200 -- about the size of an orange -- 200 cubic centimeters of brain, which left me paralyzed -- hemiplegic on the left side -- for over a year.

When I was brought out of the field by helicopter and on the way to the next medical post, I was declared dead and they had to jump start my heart a couple of times. And the hemorrhage at the point when they started to open my head up -- as I say, I've got the size of a large orange -- and I was dead at that time, so I'm told. I mean, I can't actually recall much about that, to be quite honest.

GROSS: How good has your recovery been?

PAGE: There's a bit of a limp. I don't think you ever really recover from something like that. You always -- yeah, you recover physically. I'm as -- I mean, I've been back to Vietnam 27 times. I was there this year for three or four weeks. But my agility is no -- is totally -- has always been impaired since.

Mentally, I suppose it gives you the strength to go on and do other things. Maybe something like this project. I mean, one can only say that there but the grace of God go I. I mean, one is alive and you can't sit and see certain -- somehow weep and gnash and wail about that -- that dilemma in the past. It's over.

GROSS: Horst Faas, you were wounded in Vietnam. What was your wound and what impact did that have on your life, your work, your commitment to war photojournalism?

FAAS: Well it was -- I was wounded in December, 1967 by a big rocket fragment that tore through my legs. And thanks to an American medic who somehow pulled me back and thanks to a tank driver who moved forward and loaded me and brought me back to some clearing and thanks to a helicopter pilot who came in and picked me up together with some other woundeds and thanks to surgeons who decided not to cut off my leg as they intended to do first, I was aware that I was on the way to recovery four or five days later.

And the only decision I made at that time was not to go to Honolulu or New York or anywhere, but to stay in Vietnam -- one reason being that I had total trust in military surgeons who were dealing with these problems day in, day out. And secondly, I tried to avoid having my legs broken again at the New York head office and being made a photo editor at headquarters, 'cause that would have ended the great days of photography, eh?

There's -- being in Vietnam and being around a major story of the time was always a great shot of adrenalin and we -- to put it frankly, we enjoyed ourselves much of the time.

GROSS: Horst Faas, when you look at the photographs that are collected in the new book "Requiem," I wonder what it makes you think of in terms of the impact of the work of these photojournalists?

FAAS: Well, some of the pictures were among the most-published pictures of the decade, if not of the century. Other pictures that we show in the book were not published at all, so had no impact. I think impact comes with the number of publications and the scope and the importance of the publications.

If you mean in terms of politics, we were not concerned with politics. We were not concerned with protest. We were not concerned with analyzing -- analyzing an event as far as it's good or bad. We're just trying to report what was happening and try to report fair and even-handed. And I think most of the -- most of the photographers that have their pictures in this book were good and fair reporters.

GROSS: I want to thank you both very much ...

FAAS: It's our pleasure.

GROSS: ... for talking with us about your book "Requiem" and about your own work in Vietnam. Thank you.

PAGE: Thank you kindly.

GROSS: Horst Faas and Tim Page edited the new book "Requiem," a collection of pictures taken by photojournalists who died covering the war in Vietnam.

Coming up, a Buddhist monk who was exiled from Vietnam for opposing the war.

This is FRESH AIR.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Washington D.C.

Guest: Horst Faas, photojournalist; Tim Page, photojournalist

High: Photojournalists Horst Faas and Tim Page. They've compiled and edited a book of photographs by photojournalists who lost their lives covering war in Indochina and Vietnam from the '50s to the mid-'70s. The book is titled "Requiem" (Random House). It features 135 different photographers including Robert Capa, Larry Burrows, and Sean Flynn. Horst Faas was an Associated Press photographer in Vietnam and Tim Page worked in Laos and Vietnam for United Press International and "Paris-Match." They were both wounded in Vietnam.

Spec: War; Violence; Photojournalism

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story:

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: NOVEMBER 05, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 110502NP.217

Type: INTERVIEW

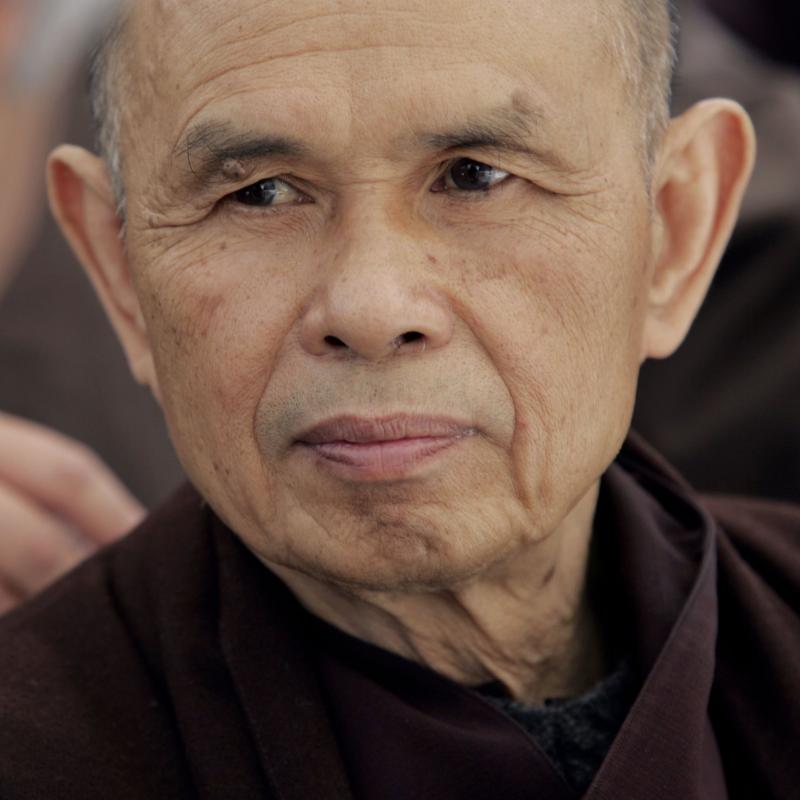

Head: Interview with Thich Nhat Hanh

Sect: News; International

Time: 12:45

FRESH AIR

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Thich Nhat Hanh is a Buddhist monk who was born in Vietnam in 1926 and has been a monk since the age of 16. He was exiled from his country in 1966 for speaking out against the war on a trip to America where he met with influential leaders of the war and the opposition. Thich Nhat Hanh led the Vietnamese-Buddhist peace delegation to the Paris peace talks.

Now, he lives in a retreat center he founded in France. His book, "Living Buddha, Living Christ," has just come out in paperback. While still living in Vietnam, he started a movement started "Engaged Buddhism" which combined meditation and anti-war work. Engaged Buddhism came out of his experiences meditating in a monastery while the war went on around him.

THICH NHAT HANH, BUDDHIST MONK, ANTIWAR ACTIVIST, AND AUTHOR, "LIVING BUDDHA, LIVING CHRIST": Like in a situation where you are sitting in your meditation at home, and if you hear the bombs falling around and the people die and got wounded. And then you cannot just continue to sit there without doing anything to help. So you begin to suffer and as you continue to suffer you try to find out a way to continue your practice while you can help the people who suffer.

And that is this situation where Engaged Buddhism was born. We try to do things out there, and that means to practice out there in the situation of suffering in the poor. And yet we could maintain our practice -- not losing our practice while being busy helping people. And that is the real -- the real setting in which Engaged Buddhism was born.

GROSS: What were some of the things that you did during wartime in Vietnam to help other people?

THICH NHAT HANH: We trained young monks, young nuns, and young people so that they become social and peace workers; come into the area where there are victims of war and to help them; to care for the wounded; to resettle the refugees; and to set up new places for these people to live; to build school for our children; to build a health center to care for the people. We did all sort of things, but the essential is that we did that as practitioners, and not just social workers alone.

GROSS: You know, the image of mindful breathing and so on is an image of stillness. And in wartime, there's often the need for flee as fast as you possibly can. Were those two things compatible? Were you able to practice stillness and the ability to run for your life when you needed to?

THICH NHAT HANH: That is a matter of training. The practice is the practice of mindfulness. Mindfulness is the energy that help you to be aware of what is going on. Like when you walk, you can walk mindfully. When you drink, you can drink mindfully. And it works when you run, you can run mindfully -- done in mindfully is quite different from just running. And that is why mindfulness doesn't mean that you have to slow down or you do things very slowly. The essential is that you are mindful -- you are yourself while you do things, whether you do it slowly or quickly.

So when you try to help refugees and if they got lost in their panics and their fear, and if you also get lost in the panic and the fear, you cannot help them a lot. Therefore, you have to be yourself. You have to maintain some kind of calm, solitude in you in order to be a real helper. That is why the practice is so important while you are a social activist.

GROSS: So even when you're running for your life, if you practice that kind of mindful running, there is a calm within you, even though you're moving quickly.

THICH NHAT HANH: Yes, I used to tell people about a boat of refugees crossing now to Thailand or to Malaysia. The boat people usually get a storm halfway or things like that, and then if -- if you panic, the boat can turn over and everyone can die. But if there is one person sitting on the boat that is calm enough, they can inspire confidence and peace, and then the whole boatload can be saved just because of one -- that one person.

So that calm, that serenity, that peace that can help you to see clearly and to know what you must do and what you must not do is very important. And to practice mindfulness is to become someone like that, for the sake of many people.

GROSS: During the war in Vietnam, when the Americans were in Vietnam, several Buddhist monks burned themselves in protest. I mean, they set themselves on fire and committed suicide to protest the war. As a Buddhist monk yourself, I'm wondering what you thought of that as a way of calling attention to the war?

THICH NHAT HANH: Before -- I think before burning themselves, they had tried other ways; trying to express their desire that the war be stopped; that people sit down and negotiate to end the war. But because of the fact that the warring parties did not listen to them, and their sound -- their voices are lost in the sounds of bombs and mortars, that is why they had to take that kind of tragic, drastic measure.

And some people say that it is an act of suicide or despair, but it's not really so because when you are motivated by the desire to end war and to help the people who suffer -- suffering that is really the energy of compassion that motivate you to do it. And burning oneself alive is just one means in order to make our aspiration understood to the world.

GROSS: Did you know those monks?

THICH NHAT HANH: I knew quite a few of them, like the monk Thit Quan Acor (ph) who was the most -- the first who immolated himself. I stay with him in his monastery for many months and we knew each other quite well. And I knew that he was a very kind, good-hearted monk. I met him in Yetan (ph) and then I met him again in the vicinity of Saigon. They are totally dedicated people. And if they sacrifice themselves, that is really for the sake of (unintelligible) and the people.

GROSS: My guest is Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, who was exiled from his home in Vietnam because he opposed the war.

We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

BREAK

GROSS: Back with Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk who became nationally known during a 1966 trip to the United States in which he spoke out against the war and met with influential leaders, including Robert McNamara and Martin Luther King.

Your trip to America to protest the American presence in Vietnam resulted in your exile from South Vietnam. What -- were you actually given an official reason for being exiled?

THICH NHAT HANH: Well, I did not intend to come and to stay for a long time in the west. In fact, I was invited by a (unintelligible) university to deliver a series of talks. And we really took the opportunity to speak about the war -- the (unintelligible) that was not heard by people outside of Vietnam because the Buddhist in Vietnam represent the majority who do not side themselves with any warring parties.

And what we wanted, really, is not a victory, but the end of the war. So what I told people over here at that time did not please any warring party in Vietnam. That is why I was not allowed to go home. And it was very hard for me because all my friends were there -- all my work was there. And I had to stay on.

But because I was already practicing as a monk, I -- mindfulness practice told me that you have to live each day of your life properly. So my practice at that time was to realize that the wonders of life were already there. In Europe, while trying to do something to end the war in Vietnam, I (unintelligible) my life and getting in touch with these wonderful, refreshing and healing inside of me and outside of me.

So in the process of working to end the war, I also practice the nursing myself and making friends and realizing that life over here is also wonderful, not just in Vietnam. And the dream start to come back.

GROSS: You ended up creating a Buddhist community in France, near the Bordeaux region. And I'm wondering what you wanted that community to be like? How you shaped it -- what you wanted it to have?

THICH NHAT HANH: First of all, I did not have the intention to picture Buddhist medication in the west, because my -- what I intended to do in the west is just to plead for an end to the war. But while I stay in the west, we need friends in order to help us to do the work, and that is why in the process of working together to end the war, I shared a practice with them.

So in the -- at the office of the Vietnamese Buddhist peace delegation to the Paris Peace talks, we really taught this in order to nourish ourselves while we continue to serve the cause of peace. And later on, many people urge us to set up a practice center so that they can get deeper into the practice. And that is why we founded the meditation center in south of France.

And now people from many, many countries come every year in the practice.

GROSS: When you teach mindfulness, you're in part teaching breathing, and breathing is really central to meditation. Why is breathing so important?

THICH NHAT HANH: In our daily life, sometime -- very often, our body is there but our mind is not there. Our mind can get lost in the past, in the future, in our worries and anxieties and fear. And you are not really there, alive. Our breath is something like a bridge linking body and mind, and as soon as you go back to your -- your breath and breathing in and out mindfully, you bring you body and mind together, and there you are again fully alive. And if you are really there, fully alive, you have a chance to touch life in that moment -- the wonders of life in that moment.

Suppose you want to enjoy the beautiful sunrise. You have to be there in order for -- to enjoy, and breathing in and breathing out mindfully can help you to be truly there. And if you are truly there and the beautiful sunrise will be there also because in the practice, we learn that life is valuable only in the present moment. And if you miss the present moment, you miss your appointment with life.

GROSS: I know that you run special retreats for refugees and for Vietnam veterans. And I'm wondering if you have a special way of teaching meditation and mindfulness to people who have been traumatized by violence in their life, by either having committed violence or being victim of violence?

THICH NHAT HANH: The practice is born from the suffering. You have to understand to know the nature of the suffering in order to offer the right practice. You know, there was -- I remember a war veteran who had committed something atrocious in Vietnam. He saw several friends of his killed in the war. He got very angry. He want to retaliate it. He push explosive -- he mix explosive in food. He made some dish and he left it entrance of a village. And he hided himself and he saw children coming and taking the sandwich and ate them.

And a few minutes after that, the children begin to cry and to crawl on earth. And their parents came and try to bring them to the hospital and he himself he knew that nothing can be done in order to help these children.

Ten years, 15 years after he return to America, he continue to suffer because of that. And he told us later, another trip, that every time he found himself in a room with children, he couldn't bear it -- had to run out of room right away. And it was with a lot of patience that we could help him to say these things, to express these things.

GROSS: Mmm-hm. Mmm-hm.

THICH NHAT HANH: And then I said -- I said there is a way that can help you to get out of this. You know that in the past, you have killed a number of children, but in the present moment there are things you can do in order to save children. And we proposed to him that children are dying in this very moment a little bit everywhere, and if he is aware of that; if he is given an opportunity to do something to save the children, and then he will not be caught in that kind of complex of guilt, and it was that kind of practice that can help people like him to restore joy -- the joy of living.

GROSS: I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

THICH NHAT HANH: Thank you.

GROSS: Thich Nhat Hanh is a Vietnamese Buddhist monk now living in France. His book Living Buddha, Living Christ has just been published in paperback.

I'm Terry Gross.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Washington D.C.

Guest: Thich Nhat Hanh, Buddhist monk

High: Writer and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh. Nhat Hanh became a Buddhist monk at age 16, worked globally for peace in his native Vietnam during the war, and has written over 75 books on peace. Some of his best-known are "Peace is in Every Step," "Being Peace," and "The Miracle of Mindfulness." His 1995 book, "Living Buddha, Living Christ" (Riverhead) is now available in paperback.

Spec: Religion; War; Violence

Copy: Content and programming copyright (c) 1997 National Public Radio, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. under license from National Public Radio, Inc. Formatting copyright (c) 1997 Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission. For further information please contact NPR's Business Affairs at (202) 414-2954

End-Story:

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.