New Memoir Describes Elvis Friendship

Elvis Presley confidant Jerry Schilling talks about his new book, Me and a Guy Named Elvis: My Lifelong Friendship with Elvis Presley. When Schilling was 12 years old, he met the teenaged Elvis Presley at a north Memphis pickup football game. As Presley rose to fame, Schilling joined him on the rise, eventually becoming creative affairs director for Elvis Presley Enterprises.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on August 14, 2006

Transcript

DATE August 14, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Boston Globe reporter Charlie Savage discusses

presidential power and changes in Justice Department

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, senior writer for the Philadelphia Daily

News, sitting in for Terry Gross.

Earlier this year, my guest, Charlie Savage, wrote a series of stories for the

Boston Globe that have touched off a national debate about the constitutional

limits of presidential power. Savage wrote that more than any other

president, George W. Bush had effectively decided that he would ignore parts

of bills enacted by Congress by issuing what are called "signing statements."

Since Savage's stories appeared, several influential legal voices have

condemned the practice, and pending legislation would allow Congress to

challenge its use. We've invited Charlie Savage back to FRESH AIR for an

update on the issue and to discuss an analysis he's written of changes in the

Justice Department's civil rights division. Charlie Savage is legal affairs

correspondent for the Boston Globe.

I asked him to explain what signing statements are.

Mr. CHARLIE SAVAGE: A signing statement is an official document that a

president enters in the Federal Register on the day that he signs a bill, and

it consists of a legal interpretation of the bill he's just signed along with

instructions to the military or the civilian bureaucracy in the federal

government about how they are to implement the bill now that it has become

law. Often these signing statements have been used, especially since the

1980s, to not just describe the meaning of the bill and the purpose of the

bill but also to raise constitutional concerns about sections of the bill. In

other words, to say that this bill may have created 10 new laws, but laws 3

and 7, I think, are unconstitutional and can be discarded or don't need to be

obeyed or enforced as Congress wrote them.

President Bush has used signing statements to challenge, at this point, I

believe the figure is more than 800 laws, or 800 provisions contained in more

than 100 bills, which is more frequent use of that mechanism than all previous

presidents in American history combined. And at the same time, he's only

vetoed a single bill, which is the least amount of vetoes since the 1800s.

DAVIES: And unlike a veto, Congress gets no chance to argue back. It's, in

effect, a final word.

Mr. SAVAGE: Correct. It's an override-proof veto and it's also a line-item

veto, because instead of having to take the whole deal that Congress hands

him, the president can say, `I will take the parts I like and discard the

parts I don't like.' And so, in two different levels, it's much more powerful

than a constitutional veto.

DAVIES: What are some of the substantive areas that the president has used

this method on?

Mr. SAVAGE: Overwhelmingly, the laws that President Bush has raised

constitutional concerns about are laws that place restrictions or requirements

on his own powers as president. Many of them involve rules and regulations

for the military, for example, famously the torture ban. Also restrictions

against using US troops that are stationed in Columbia to engage in combat

against rebels. Other sorts of national security provisions such as oversight

requirements that were put in the Patriot Act reauthorization bill in March,

as well as many restrictions and requirements on the civilian side of the

executive branch, such as whistleblower protections for executive branch

employees who bring information to Congress without the president's

permission, affirmative action provisions, safeguards against political

interference in federally funded research.

DAVIES: One of the areas that you mentioned President Bush had used a signing

statement to make a substantive change involved the torture of--the use of

torture of detainees. Remind us of that congressional debate. What happened

there?

Mr. SAVAGE: Last year Senator John McCain led a long fight in Congress to

pass a law that would make clear in US law that it is illegal for US

interrogators to use torture, cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment when

interrogating a detainee, no matter where in the world that detainee is held.

President Bush and Vice President Cheney lobbied vigorously against that

change in US law, which some people thought was not a change at all but merely

a clarification of a pre-existing anti-assault ban, and they threatened to

veto it. But, at the end of the day, overwhelming majorities in both houses

passed it, and President Bush called a press conference and told the world he

was accepting this restriction, in fact, maybe it was a good idea. It would

help us, you know, with our image. But when he signed the bill a few days

later, President Bush quietly attached a signing statement to the bill, and

one of the reservations he made in the signing statement was that this new

law, the detainee treatment act which banned cruelty, could not bind his hands

because he was the commander-in-chief and the Constitution gave him the power

to fight wars as he saw fit. And so Congress could not absolutely ban torture

in a no-exceptions way as Congress had intended to do, because it was up to

him as commander-in-chief.

DAVIES: How did congressional leaders react after such a vigorous debate on

this issue?

Mr. SAVAGE: Well, initially they didn't know it had happened because no one

was used to reading these statements. They were being quietly filed in the

Federal Register and never heard from again outside the executive branch.

When I wrote a story about this signing statement, there was anger from the

Republican senators who had been the primary sponsors of that torture ban.

Senator McCain, Senator John Warner, who's the chairman of Senate Armed

Services Committee, and Senator Lindsey Graham--all Republicans--put out

statements saying, `Wait a minute, you know, you knew--you asked us for a

waiver, if you thought that there was some need to use harsher techniques, and

we considered it and we chose not to give that to you. This law means what it

means and we're going to try to--we going to make sure through oversight that

it's enforced as we wrote it.' And then after that flurry, there wasn't a lot

of discussion again about it for a while.

DAVIES: Now Senator Arlen Specter has also been interested in this. He has

held hearings and introduced legislation affecting signing statements. What

would that legislation do?

Mr. SAVAGE: Senator Specter held a hearing on signing statements and grilled

a Bush administration attorney to justify this extensive use of them, and he

subsequently introduced a bill called the Presidential Signing Statements Act

of 2006. The main thing that the bill would do is it would enable Congress as

an institution to sue the president if the president issues a signing

statement raising some claim about a bill that the Congress has passed so that

a court could review those legal claims, because the great problem with these

signing statements in particular is that no one has legal standing to file a

lawsuit over them and therefore there's no way for the judicial branch to

review them. Senator Specter is trying to solve that problem by saying that

it's Congress itself which is damaged in some way when its ability and its

right to write the law is being compromised in this measure. And so Congress

as an institution ought to be able to file a lawsuit and then get the issue

before a judge so that the courts could undertake a substantive review of the

merits of whatever the legal claim the president is making about this bill

that Congress just passed.

DAVIES: Now the American Bar Association has also expressed its sentiments on

the issue of signing statements. What did they conclude?

Mr. SAVAGE: The American Bar Association appointed a blue ribbon panel of

Republicans and Democrats, retired judges, law school deans, former Reagan

officials, former Clinton officials to study the issue of signing statements,

and they issued a unanimous report last month, which called on all presidents

to no longer use signing statements to say that some part of a bill they're

signing need not be enforced.

Earlier this month the American Bar Association's House of Delegates voted to

endorse that finding, so it is now the policy position of the world's largest

body of legal professionals. Essentially this position says that presidents

do not have the power to sign a bill into law and then not enforce some

components of that bill on the grounds that those components are

unconstitutional. The ABA is saying that presidents only have the power to

veto a bill and then give Congress a chance to fix it or override the veto.

Or if they choose to sign the bill, the president has to enforce all of it.

This position has been both praised and criticized. It's been praised because

it's not an attack on President Bush per se, but a bipartisan, above-the-fray

institutional argument, which sweeps in other presidents, including Bill

Clinton, who also used signing statements to challenge laws, albeit not as

intensely as the current one has. But it's also been criticized, including by

a group of former Clinton administration attorneys, who say that it's getting

it wrong, it's focusing on the wrong issue. They say that presidents need the

power to not enforce a component of a law that's unconstitutional but still

sign the legislation because Congress lumps so many laws together in a single

bill these days that it's just impractical to veto it. The problem they say

is that President Bush is pushing an extreme view of his own powers, but a

president who has a more mainstream view about what is and is not

unconstitutional ought to still be able to use signing statements.

DAVIES: Have any disputes or litigation reached the Supreme Court, which

might test the legal validity of signing statements?

Mr. SAVAGE: Courts have very rarely mentioned signing statements. And,

again, this gets into the question of whether the signing statement as a

mechanism or the legal views being advanced in a particular set of signing

statements is the issue. Interestingly, in the most recent high-profile

Guantanomo case that was decided in June, where the Supreme Court struck down

President Bush's military commission trials, both of these aspects did come

into play. First of all, in their dissent to a portion of the decision,

Justice Antonin Scalia, who was joined by Alito and Thomas, mentioned

President Bush's signing statement on the Detainee Treatment Act, and that was

a rare instance in which it was being brought up, although he was doing it in

the context of legislative history, `What does this law mean and what does it

not mean?'

DAVIES: And did they mention it in such a way that suggested they thought it

was a guiding legal authority?

Mr. SAVAGE: Well, certainly to bring it up as relevant evidence does suggest

that. On the other hand, Justice Scalia generally is very skeptical about the

use of legislative history in general, and was using it to rebut the--how the

majority had come up with their interpretation of what the law meant. And so

it's difficult to know what to make of that.

But the other thing that happened in that opinion was that--in the majority

opinion--was that they struck down President Bush's military commission trials

because Congress had already passed a law that had governed military

commissions and President Bush had ignored it and gone off and created a

different system under his own desires, and that sort of action by the

president is at the heart of a lot of the claims that he has been making in

the signing statements, essentially Congress--he's beyond the reach of

Congress when it comes to especially matters of national security, that

statutes cannot bind him, that he's going to fight the war the way he sees

best, and because he's commander-in-chief, the Constitution gives him the

power to do that. The Supreme Court majority said, `No, Congress has spoken

here. You've got to obey this law, or you have to ask Congress for permission

to depart from it, and so you need to go back to the drawing board.' That is a

repudiation of a lot of the claims of executive power that President Bush is

making.

DAVIES: Since your piece this spring sparked this controversy, we've had a

number of groups weigh in on it. We've had, you know, one piece of

legislation introduced. What happens next on this issue, do you think?

Mr. SAVAGE: Well, one thing that we'll have to watch to see is whether the

legislation that Senator Specter has filed goes anywhere. Does he try to push

it through in the sort of late towards-the-election climate, or does it just

sort of die on the vine, as it were? And we'll also have to watch for what

signing statements come out of the White House next when the more major

legislation goes through. And we'll have to see to what extent this becomes

an issue in the '06 and even the '08 campaigns.

DAVIES: We're speaking with Charlie Savage. He is the legal affairs

correspondent for the Boston Globe. We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, my guest is Charlie Savage, legal affairs

correspondent for the Boston Globe. He recently took a look at the Justice

Department's civil rights division, examining its hiring practices and how

they've affected the unit's operation. I asked him to describe how the

department historically evaluated job applicants and how that's changed.

Mr. SAVAGE: Up until 2002, when there was a vacancy in career lawyer ranks

of the civil rights division at the justice department, hiring committees

composed of other career professionals would come together and go through

thousands of resumes, decide whom to interview, conduct the interviews and

recommend who to hire to fill that vacancy. And the political appointees in

the front office would have to give final approval to that, but only rarely

were the recommendations turned down. And that's how it worked for decades

under both Republican and Democratic administrations. In the fall of 2002,

then Attorney General Ashcroft changed those rules. The hiring committees of

other career attorneys were essentially disbanded, and the entire process from

start to finish was put under the control of political appointees. And from

that point on, the profile of the type of attorney who's being hired to

enforce the nation's civil rights laws and who--in a career position that will

stay on after the next presidential election changed dramatically.

DAVIES: And what did you find, in terms of the kinds of lawyers hired, both

in terms of their professional experience and in terms of their political

history or ideological profile?

Mr. SAVAGE: What I found was that after the change--the rules for hiring

were changed to give political appointees greater control over the hiring

decisions, the attorneys who were being hired into the civil rights division

career positions were much less likely to have a traditional civil rights

background and much more likely to have strong, conservative credentials. For

example, prior to the change, 77 percent of those who were hired had civil

rights backgrounds, which means either they had been litigators on civil

rights issues, especially for groups like the NAACP and so forth, or if they

were fresh out of law school, they'd been members of civil rights clubs and

they had worked on civil rights issues as summer interns.

After the change, only 42 percent of the lawyers hired had any kind of civil

rights law background. And almost half of those had not gained their

experience by working to enforce traditional civil rights causes but rather to

resist them by defending employers against discrimination lawsuits, by working

against affirmative action programs, by working against minority/majority

voting districts, which are designed to help minorities.

DAVIES: Clearly this is an administration with a different ideological

orientation than the last one. Is it possible that it simply got different

kinds of applicants, that lawyers with a different kind of political and

ideological bent were inclined to apply?

Mr. SAVAGE: That's certainly possible and no doubt is one of the factors

here. However, when you talk to career people who've been there for quite a

long time, they point out that previous conservative administrations, such as

the Reagan administration, also had a different perspective on civil rights.

But during those periods when the old hiring procedures were still in place,

the people who joined the division were still by and large interested in

enforcing civil rights in a traditional way, and the political appointees at

the top of the division may have been redirecting the priorities in certain

ways that ended when that term was up and those appointees moved on. But

there was not this wholesale change in the character of--or the profile of the

attorney, such that people who had no civil rights experience at all were

suddenly flooding the division and who instead were members of the Federal

Society, members of the National Republican Lawyers, and so forth.

DAVIES: You said earlier that hiring practices had changed and that career

professionals had taken more of a role in reviewing candidates and

recommending them for hiring decisions. What is the Bush administration's

defense of their hiring practices and litigation approach?

Mr. SAVAGE: Well, the official line from the Justice department is that

there are no political overtones to the changes in the hiring procedures, that

there is no political litmus test. Other defenders of the administration who

are no longer working for the government, and are perhaps a little bit freer

to speak candidly, have a little different approach. They say that the civil

rights division permanent bureaucracy was an entrenched group of liberal

lawyers who did not necessarily share the president's view of how civil rights

laws ought to be enforced, and that it's appropriate to bring in more

conservatives who can maybe offer some balance to this bureaucracy.

DAVIES: How has the work of the civil rights division changed under this

administration, in terms of the actual cases they pursue and the way they

function?

Mr. SAVAGE: There's no doubt that there's been a shift in priorities of the

kinds of civil rights cases that this division has been bringing at the same

time as the types of attorneys that it's been hiring to develop cases has

shifted. Under the Bush administration, the civil rights division is filing

fewer lawsuits alleging ferreting out systematic discrimination against, for

example, African-Americans, and at the same time it's instead hiring--filing

more cases intended to protect white people from reverse discrimination and to

protect religious groups, particularly Christian groups, from religious

discrimination.

DAVIES: How are those cases doing in the courts? I mean, presumably, if

those represent, you know, bona fide applications of the nation's

anti-discrimination statutes, the courts might smile on them. How are they

succeeding in these reverse discrimination cases?

Mr. SAVAGE: Some of them are being settled without going to court. For

example, the civil rights division threatened to sue Southern Illinois

University over some fellowships that had had which were to help women and

minorities get graduate degrees, and they threatened to sue the university

over that saying that that was reverse discrimination against white men. And

rather than fight the case, the university just agreed to scrap the program.

I think, in general, it's fair to say that these cases are doing fine.

They're not illegitimate cases. It's a question of priorities. Traditional

civil rights enforcement advocates would prefer to see this division working

on behalf of women and especially racial minorities, which was the purpose of

the division when it was first founded, and conservatives think it's better to

focus on these other kinds of cases.

DAVIES: Well, Charlie Savage, thanks so much for speaking with us.

Mr. SAVAGE: Thanks for having me on.

DAVIES: Charlie Savage is legal affairs correspondent for the Boston Globe.

I'm Dave Davies and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

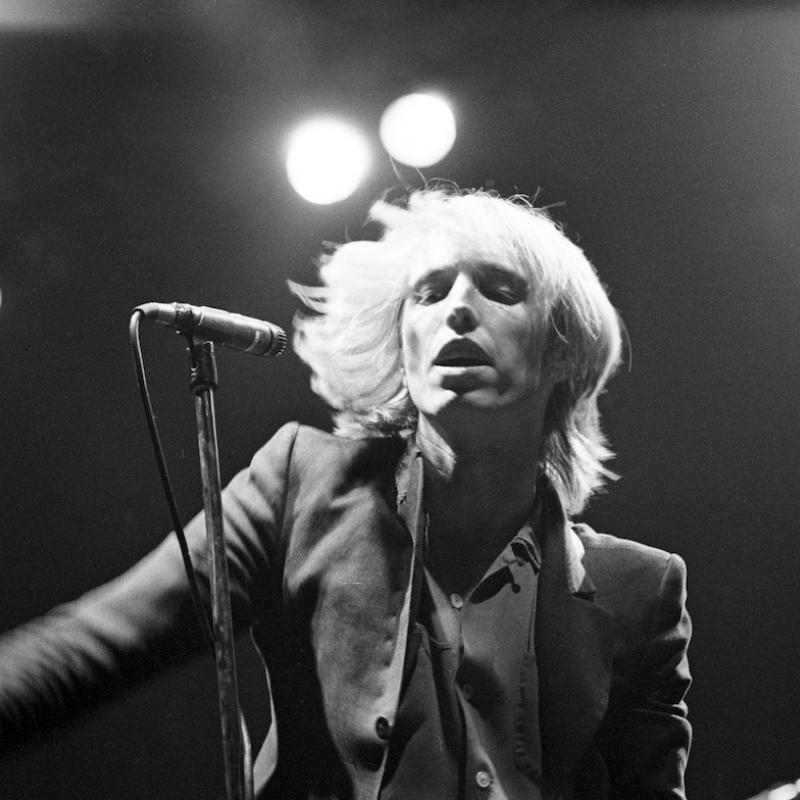

Interview: Author Jerry Schilling discusses new book "Me and a

Guy Named Elvis: My Lifelong Friendship with Elvis Presley"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies filling in for Terry Gross.

Jerry Schilling was a poor 12-year-old kid in north Memphis when he first met

Elvis Presley, then a 19-year-old truck driver who was just beginning the

singing career that would make him an American music legend. Schilling became

friends with Elvis and eventually joined the crew known as the "Memphis Mafia"

that traveled with Elvis through years of concerts, movie shoots, and

recording sessions, and plenty of downtime in Hollywood, at Graceland, and at

movie theaters and amusement parts that Elvis would rent for get togethers.

Now, 29 years after Elvis's death, Schilling has written a memoir of their

friendship. He describes an Elvis who was a voracious reader and a spiritual

seeker, a man who was both temperamental and extravagantly generous with his

friends, and a performer who was artistically frustrated. His book is called

"Me and a Guy Named Elvis: My Lifelong Friendship with Elvis Presley." Before

we get to our conversation with Schilling, let's hear Elvis's first hit,

"That's All Right."

(Soundbite of "That's All Right")

Mr. ELVIS PRESLEY: (Singing)

Well, that's all right, Mama,

That's all right for you

That's all right, Mama,

Just anyway you do.

That's all right

That's all right

That's all right now, Mama

Anyway do

Well, Mama she done told me

Papa done told me too

`Son, that gal you're fooling with,

she ain't no good for you.'

But that's all right

That's all right

That's all right now, Mama

Anyway do

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: Your relationship with Elvis began in the most ordinary of ways.

When I first read this in the notes, I couldn't believe this could actually be

true. But you really did meet him playing touch football, right?

Mr. JERRY SCHILLING: Yeah, in north Memphis, our local playground. I was a

kind of lonely kid, just--not even a teenager. I was 12 years old. And I

went to the park one Sunday afternoon, and there were five older guys trying

to get up a football game. This is how unpopular Elvis Presley was in July of

1954. And one of the older boys who was a friend of my older brother said,

`Jerry, you want to play with us?' And I said, `Sure.' And I went in the

huddle and the other player was Elvis Presley, a 19-year-old who had just

recorded. His record had been played locally two nights before on Dewey

Phillips "Red, Hot and Blue Show" in Memphis. And when I looked at this guy,

I went, `Oh, that's the guy I heard on the radio the night before last.'

DAVIES: What was the record?

Mr. SCHILLING: "That's All Right, Mama." That was the--he had recorded it

that week, I think around the first part of the week. And I--this was a

Sunday afternoon. I had heard the record Friday-Saturday night or

Thursday-Friday night, and it was 7/11, July 11th, 1954, when I met Elvis and

we played touch football.

DAVIS: So you met Elvis on the football field. He was the quarterback in the

huddle. Did you have any particular impression of him? You obviously were a

starstruck kid and fascinated by the fact that he had made this great record.

Did he have any particular presence as a quarterback?

Mr. SCHILLING: Well, you know, he was--he had a presence that was

approachable and unapproachable at the same time. Something like a presence

that when people develop as a star, you kind of get that thing, you know,

where, you know, you hope they like you but you're not sure. Elvis had that

before he was a star. He was just--I kind of think of him as this lovable

rebel, if you will. He wasn't somebody I was going to run up and slap on the

back as a buddy, and yet, you know, he also--there was a kind of a

friendliness that showed through and then an edginess on the other side.

DAVIES: It was fascinating to read the description of your book how as his

popularity grew, he continued to show up on Sundays and play touch football.

And people began to come and watch because they heard this hot young guy,

Elvis Presley, was out here playing touch football. And he was controversial

at the time, because, you know, he touched some hot buttons. Some people

didn't like some of the stuff that was in his music. And you tell a

fascinating story of some semi-pro football players who come up and want to

mess with Elvis. Tell us that story.

Mr. SCHILLING: We were playing--we were probably into about our first year,

still playing at the same little park in north Memphis. Elvis was a creature

of habit. We played every Sunday he was home. And these two big semi-pro

guys came over to play. And everybody kind of stood back a little bit, and

Elvis said, `Yeah, sure, you guys can play.' And so we got into the huddle, we

came out, and Elvis would switch from quarterback from time to time, and he

was on the line and this guy just ran right over him. We were all like, you

know, `Come on. I mean, the guy's, you know, he's got a recording career,'

we're thinking to ourselves. So Red West--one of the other guys with us,

tough guy, the guy that called me over to play football that first day. Said

Red, `Elvis, I'll take him this time.' And Elvis said, `No, no, no. Just go

on and play your position, Red.' He got run over again. And finally about the

third time, Elvis said something to the effect, `You want to try the other

side?' And the guy said, `What do you mean?' He said, `Well, all my bones are

broken on this side.' And the guy started laughing and they realized that

Elvis wasn't some guy who was going to, you know, try to be something special

or whatever. He'd get down nose-to-nose with you. So these two guys who had

given us so much trouble--I mean, we were ready to fight them. And Elvis kind

of knew what he had to do.

DAVIES: My guest is Jerry Schilling. His new book is "Me and a Guy Named

Elvis." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: If you're just joining me, my guest is Jerry Schilling. He has a new

book out "Me and a Guy Named Elvis." It's the story of his many years

friendship with Elvis Presley.

Eventually he hires you to come and work for him, and it's a fascinating

moment. By this point you're a little older. You've finished high school, I

believe, and had done some college. And he says, `I want you to come and work

for me.' And I guess it was the first day or two that they're packing up

to--from Graceland to head out to California to make Elvis's next movie, and

the traveling arrangements I found fascinating. Describe how Elvis traveled

to California to film.

Mr. SCHILLING: Well, first of all, you know, Elvis never was a cross-country

truck driver. He drove a little panel truck in Memphis at an electrician

company that he worked for. But, boy, when it was time to travel to

California, we had this Dodge mobile home, and Elvis drove every mile of it.

He would, you know, he put his driver's gloves on. He'd have this scarf on,

and kind of this motorcycle hat that, if you will, kind of like out of "The

Wild Ones," with Brando. He would have a reel-to-reel tape player with

whatever music he was into at the time. And I loved those trips.

And this first trip--there was one thing. I had known Elvis for 10 years,

prior to going to work for him in 1964, which was my senior year in college.

And I was just getting ready to be a history teacher and I was to practice

teach when he asked me to go to work for him. And that one trip from Memphis

to Los Angeles, which took us about nine or 10 days--we stopped at truck stops

and played football. We were in hotel rooms talking all night. But I got to

know Elvis more in that one week and a half than the 10 years I had known him

before.

DAVIES: It was also on those trips that you realized he was taking pills and

the rest of you started taking them, too, right? What kinds of drugs were

going on then?

Mr. SCHILLING: Well, you know, I was considered the health fanatic of the

group. They used to call me "Mr. Milk" because I was playing college

football and I was working out all the time. And as we took these all night

trips across country, I think, to stay awake for Elvis. Something that he had

picked up in the army over in Germany, Dexedrine pills would keep you awake

and, you know, you could play some pretty damn good football games with that

as well. And then, you know, so somebody slipped me one once and I tried it,

and I think I was going out for passes for about three days. And then you get

to a point where you can't sleep, and then you get a sleeping pill, and that's

basically what it was in that period. We would take Dexedrine to keep going,

because Elvis never wanted to quit, especially when he was having a good time.

Whether it was on the road, playing football, or if we were in Vegas, he would

want to go to show, to show, to show. And, you know, you can go 24 hours.

Sometimes we would stay up two or three days. And then you crash and then you

sleep for two or three days. It's not anything I would recommend to anybody

and--but, you know, it was before we knew a lot and it was prescribed

medication from our doctors. And, you know, I looked at it like this, `Hey,

this guy's the best good-looking guy I've ever seen. He's the most talented

guy. He's fun to be around, it's got to be good for you.'

DAVIES: You describe a lot of time hanging out in Los Angeles, in Graceland,

before, after shows. Mostly guys hanging out. There must have been a lot of

women in Elvis's life, I mean, certainly stories of that. Where do they fit

into the picture?

Mr. SCHILLING: Well, normally when we hung out, there was women there with

us. If not our girlfriends, then later on our wives and whatever. But even

when we were by ourselves, coming out to Los Angeles to do movies, there was a

group of girls that--they were really friends, not dates--that Elvis enjoyed

their company. They were included a lot. And then, of course, the people

that we were dating. But there were a lot of girls, trust me.

DAVIES: And some, I mean, was Elvis a philanderer? Did he fool around?

Mr. SCHILLING: You know, Elvis basically was a one-on-one guy in a

relationship in general. And then you take that he was Elvis Presley, yeah,

of course, I mean, if his girlfriend was living in Memphis and we were on the

West Coast, he would have a girlfriend here. He was, you know, he was Elvis

Presley. I mean, it was very tempting. I mean, I can't just blame him. We

were all that way to a certain degree. I just think if I had been Elvis

Presley, in his shoes, I would have probably even had more girlfriends.

Just--he liked to have relationships, you know.

DAVIES: Relatively restrained, given the opportunities.

Mr. SCHILLING: Yeah.

DAVIES: You know, you grow a lot after you get out of high school. I mean,

that's a time in people's lives when they undergo a lot of change, whether,

you know, you're going to college and stretching your mind or entering the

working world and, you know, understanding what that requires living as an

adult. And here you have Elvis Presley who, immediately after high school,

becomes incredibly rich, incredibly famous, and inevitably then surrounded by

relationships of any quality, even with friends, like you, you know. There's

also an employer-employee relationship. And he's in a situation where he can

indulge, you know, any annoyance or grudge. He never has to kind of humble

himself and take the guff that most people do, and he grows up this way in his

20s. And I'm wondering if you've ever thought what the effect was on Elvis's

personality of sort of--at such a young age to be so, kind of, entitled to

indulge his moods?

Mr. SCHILLING: You know, I have thought about that a lot, even when I was

with him, and I've thought about it since. You mature real fast. What

happens when you're in that position, you're the center of attraction, not

just when you're on stage or in front of a camera, when you wake up in the

morning. Everybody else is your friend, they're your employee, and their

whole life centers on your mood that day. And Elvis handled that pretty damn

well. I never felt--when I lived at Graceland and worked with Elvis--I never

felt that I wasn't a part of it. Push come to shove, and every great once in

a while when he'd be upset, you know, you realize, `OK, I work for this guy

and this is how it's going to be.' But on a day-to-day basis, we truly lived

as brothers. And that was because he understood. He wanted--first of all, he

was a loner as a kid. When you move at 12 years old, 13 years old, from one

state, like Mississippi--and he was in rural poverty Mississippi--and he moved

to our neighborhood, which was poor north Memphis. If you look at "Hustle &

Flow..."

DAVIES: Mm-hm.

Mr. SCHILLING: ...that's where it was filmed, right there in our

neighborhood, same houses and everything still there. And so Elvis's dream,

like a lot of lonely kids, was to have friends and to share things with. And

Elvis got that pretty good. I think it was harder for the people, the family,

the uncles, and whatever, and the aunts and cousins, and us guys, to get used

to living that kind of life, and accepting that. I mean, some of the guys

didn't make it, some of the families didn't make it. It's--Elvis....

DAVIES: What do you mean by didn't make it, Jerry?

Mr. SCHILLING: I think, well, there was a couple of the cousins right in the

early days that went off the deep end, took too many pills, died at early 20s.

It blew a lot of people's minds who were close to Elvis, what happened to

Elvis.

Elvis was a pretty constant force. When you're in that position, too, you

have a tremendous amount of power. You can look at somebody wrong and really

do some damage, and Elvis never abused that. He didn't abuse that power. He

understood, you know, what he had. When you did see--at times, he was a human

being, and at times, with us that knew him, he let it flow. I'd never see a

temper. I'd never seen a more angry guy in my life. So I've always said, one

of the reasons why I love him even that much more, he just wasn't a

good-looking guy with a good voice, the boy next door. He had all of those

other traits and he chose 90 percent of the time to be a nice guy.

DAVIES: Jerry Schilling, you know, one of the most important influences in

Elvis's professional life was his relationship with Colonel Tom Parker, who's

been criticized for, you know, manipulating him and making him do far too many

shows, far too many records, and doing a lot of weak material. I mean, people

sort of--some blame him for sort of driving Elvis to an early grave. I mean,

you saw that relationship a lot. What did you observe of Elvis? What was

your sense of Elvis's relationship with Colonel Parker?

Mr. SCHILLING: Overall, the Elvis Presley-Colonel Parker relationship was a

very successful, very special relationship. I think there was a period where

Elvis outgrew the colonel, mostly in creativity. I think, as great as Elvis's

career was, I think, the people in charge always looked at him as a short-term

artist. They thought maybe long-term. But Elvis always knew. I mean, he was

a genius at what the public wanted, and he knew that if the movies were the

same thing, you know, with different songs and different locations, that

people would get tired. But he predicted way before it happened. And he was

a genius that needed creative challenges, and he would come up with them

himself from time to time.

And then it was, you know, whether it was the studios or record companies or

whatever, they didn't want to pay. They paid top dollar for Elvis Presley,

and they didn't really want to pay top dollar for co-stars, for scripts. And

Elvis creatively suffered from that

Elvis on creative disappointment. The drugs were the Band-Aids, but I go back

to the cause of--and I put specific examples. And I was in meetings--I was in

between Elvis and the Colonel about overseas touring. I observed a

heavyweight meeting when Elvis would not do this movie because the script was

so lame. I was in a walk-in dressing room closet when Barbra Streisand

offered Elvis "A Star Is Born," and I knew what that meant to him creatively.

I think the Colonel truly had a love and respect for Elvis. I just think at a

point it was too old school. He probably would have liked Elvis to be closer

to Bing Crosby than the rock star that he was. You know, the Colonel is an

easy target. He probably did most of the things right and some of the stuff

that--you can't blame a guy for what they don't know. The Colonel was not a

creative genius. He was a business genius.

DAVIES: Jerry Schilling's book about his friendship with Elvis Presley is

called "Me and a Guy Named Elvis." We'll be back after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: My guest is Jerry Schilling. He's written a new book called "Me and

a Guy Named Elvis" about his long-time friendship with Elvis Presley.

In Elvis's later years, when he was doing his Vegas act a lot, there are a lot

of stories about him getting sloppy, forgetting or improvising lyrics and, you

know, rambling monologues. How accurate is that picture? What did you

observe?

Mr. SCHILLING: You know, again, it goes to the creativity challenges, and

unfortunately there was a period in the last couple of years of Elvis's career

where he was bored out of his mind playing the same room, all these shows.

And he started kind of entertaining himself or working to one audience or

whatever, and the shows really did suffer for it. I--one night, actually,

about 300 people walked out. I never thought I'd ever see that, people walk

out of an Elvis show.

DAVIES: What did he do that caused them to walk out?

Mr. SCHILLING: I think he played to one table and started joking around, and

this one table loved it, you know. They had the star of the show playing to

them. We were all kind of panicked. He probably did four songs in the whole

hour of this performance. And that's one of the nights where the Memphis

Mafia, afterwards, we all got together and confronted Elvis, and he kind of

laughed at first, like `Well, what do you mean? These people really enjoyed

it.' And Lamar, one of the guys with us, said, `Yeah, Elvis, but 300 people

walked out.' And then Elvis fired back at him. And I said, `Elvis, of course,

the one table you played to is going to like it.' And then he just kind of

froze and said, `Call the Colonel.' That's how bad it got.

DAVIES: There was one episode where a man jumped up on a stage in '73 and

Elvis becomes convinced that he was sent by a karate instructor that his

former wife Priscilla had dated, and then his behavior just got more and more

bizarre, right? What did he do?

Mr. SCHILLING: Yeah. Well, you know, this is a period where I think three

major things was happening to Elvis. His health was getting bad. He didn't

like the idea of being 40. He was going through a divorce--which he wanted

and didn't want--and he was trying to keep his manhood up and his image up.

And he put a lot of that into karate, even incorporating it on stage.

So one night, a couple of guys did jump on--actually four--but one guy jumped

on stage and then another guy. And through all of this--things that were

happening to Elvis, he was convinced that Priscilla's boyfriend, Mike Stone,

who was a really tough karate guy--he'd never lost--had put this into motion.

And we just couldn't convince him differently, after we found out, you know,

the background on the people and everything.

DAVIES: And he started talking about having Mike Stone killed, right? Yeah?

Mr. SCHILLING: Yeah, it came, you know. It--there were calls made. It was

ready to go actually. And I think when Elvis realized he could do this, it

scared him to death. And we were sitting at this table, dinner at Las Vegas,

and I didn't hear the conversation. I knew what the conversation. I was down

at at the other end of the table. And I saw Elvis turn white and go, `Well,

you know, I don't think we have to go that far, you know. Let's forget about

it for right now.' He never mentioned anything like that again.

DAVIES: Well, Jerry Schilling, thanks so much for spending some time with us.

Mr. SCHILLING: My pleasure, Dave. Thank you.

DAVIES: Jerry Schilling. His book "Me and a Guy Named Elvis" comes out

Wednesday, on the 29th anniversary of Elvis Presley's death.

(Credits)

DAVIES: For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

(Soundbite of "A Little Less Conversation")

Mr. PRESLEY: (singing)

A little less conversation, a little more action, please

All this aggravation ain't satisfactioning me

A little more bite and a little less bark

A little less fight and a little more spark

Close your mouth and open up your heart and, baby, satisfy me

Satisfy me, baby

Baby, close your eyes and listen to the music

Drifting through a summer breeze

It's a groovy night and I can show you how to use it

Come along with me and put your mind at ease

Hey

A little less conversation, a little more action

All this aggravation ain't satisfactioning me

A little more bite and a little less bark

A little less fight and a little more spark

Close your mouth and open up your heart and baby satisfy me

Unidentified Backup Singers: Oh, baby.

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me, baby

Singers: Oh, baby.

Mr. PRESLEY: Come on baby, I'm tired of talking

Grab your coat and let's start walking

Come on, come on

Singers: Come on, come on

Mr. PRESLEY: Come on, come on

Singers: Come on, come on

Mr. PRESLEY: Come on, come on

Singers: Come on, come on

Mr. PRESLEY: Don't procrastinate

Don't articulate

Girl, it's getting late

Gettin' upset waitin' around

A little less conversation, a little more action

All this aggravation ain't satisfactioning me

A little more bite and a little less bark

A little less fight and a little more spark

Close your mouth and open up your heart and baby satisfy me

Oh, baby, satisfy me

Singers: Oh baby

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me, baby

Singers: That's my baby

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me, girl

Singers: Come on, come on, come on, come on

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me, baby

Singers: That's my baby

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me

Singers: Come on, come on, come on, come on

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me, baby

Singers: That's my baby

Mr. PRESLEY: Satisfy me, girl

Singers: Come on, come on, come on, come on

(End of soundbite)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.