Letterman And 'Tonight' Vet Go Behind The Scenes Of Late Night

Fresh Air kicks off its late night TV theme week with a 1981 David Letterman interview, in which the host describes how late night TV changed the comedy business, and a 1988 interview with one-time Tonight Show executive producer Fred de Cordova.

Guests

Contributor

Related Topics

Transcript

August 26, 2013

Guests: David Bianculli (co-host) - David Letterman - Fred de Cordova

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Today, we start a special, week-long series with some of the stars of late-night TV. We'll feature interviews from our archive with Jay Leno, who retires from "The Tonight Show" early next year; Jimmy Fallon, who will become the new host; Questlove, whose band The Roots is moving with Fallon from "Late Night" to "The Tonight Show"; Jimmy Kimmel, who Fallon will soon be competing against at 11:35; and Conan O'Brien, who hosted "Late Night" and "The Tonight Show," then moved to TBS.

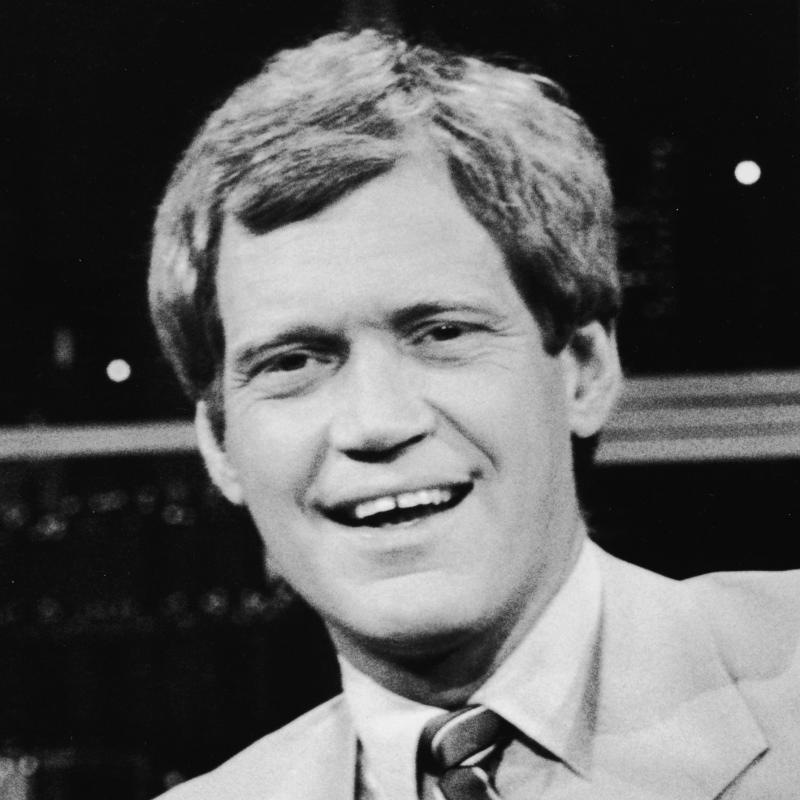

On this first day of our series, we're going deep into our archive for an interview I recorded with David Letterman back in 1981, when FRESH AIR was a local radio show in Philadelphia, and Letterman was in town to perform at a club. This was an in-between period of his life. It was the year after his morning show was canceled, and the year before he started "Late Night with David Letterman."

At the time, he was best-known as one of Johnny Carson's guest hosts on "The Tonight Show," which is one of the things we talked about. I wish I could say we'll also feature an interview from the archive with Johnny Carson. I can't. But we will hear a 1988 interview with Carson's longtime producer, the late Fred de Cordova. Our TV critic David Bianculli is with me for today's show and to start us off, he's going to tell us about the early days of late-night TV. And he's brought some great clips.

Welcome, David, and thank you for helping us kick off our late-night week. Late-night is such a staple of television now. Let's go back to a period where it wasn't. Like, where does late-night actually start?

DAVID BIANCULLI, BYLINE: It started with local shows out of New York, one during the war on a DuMont station, and that was hosted by a vaudevillian named Jerry Lester. And then in 1950 or thereabouts, Steve Allen had a local show. And Jerry Lester got the first network show, which was "Broadway Open House." And that went from 1950 to 1952, when there wasn't anything else on late at night. And then that was replaced a couple of years later by "The Tonight Show" in 1954, when Steve Allen went from local New York to national.

GROSS: So let's hear the tape that you've brought with you of the opening night of "The Tonight Show"; the very first broadcast, with Steve Allen as the host.

BIANCULLI: OK.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST, "THE TONIGHT SHOW")

UNIDENTIFIED ANNOUNCER: From New York City, the National Broadcasting Co. presents "Tonight," starring Steve Allen.

(AUDIENCE APPLAUSE)

STEVE ALLEN: This is "Tonight," and I can't think of too much to tell you about it, except I want to give you the bad news first. This program is going to go on forever.

(AUDIENCE LAUGHTER)

ALLEN: Boy, you think you're tired now. (Laughter) Wait till you see 1 o'clock roll around. It's a long show, goes on from 11:30 - here in the East, that is - from 11:30 to 1 in the morning. And we especially selected this particular theater. This is a New York theater called the Hudson, and we especially selected this for this very late show because this theater, oh, I think it sleeps about 800 people.

(AUDIENCE LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That was the opening of Steve Allen's first night hosting "The Tonight Show" in 1954.

BIANCULLI: Yeah, the first national show.

GROSS: Wow. And it's like he's explaining to the audience you're going to have to be up really late, like 1 a.m.

BIANCULLI: Well, it was all new. I mean, the territory was new. Asking people to stay up until 1 o'clock was new. And I think of Steve Allen the way I think of, you know, Ernie Kovacs. These were guys who saw TV as a toy and wanted to play with them. And Steve Allen was interested in so many things, and had so many talents that a lot of what he did became the templates for the talk shows to come. I mean...

GROSS: Like what?

BIANCULLI: Well, he had a really insatiable thirst for doing some serious interviews, as well as being straight man when a comic would come on. And so you think of, like, Johnny Carson doing, you know, Carl Sagan, that sort of thing. That was started by Steve Allen. And then you have the repertory comics, the different recurring sketches that he would have.

And he was a jazz musician, and he loved jazz and loved music and had all sorts of acts on. And he also showcased young comics. Lenny Bruce was on his show. It was a true variety program. You know, it wasn't quite so structured as what we think of as a Johnny Carson "Tonight Show," but the elements were there.

GROSS: Did Steve Allen do an opening monologue?

BIANCULLI: Not always, and not in that way. He had the show for three years, and then Jack Paar took it over. Jack Paar was the first to really do what we think of as a monologue. But his was more stream-of-consciousness.

GROSS: More anecdotal.

BIANCULLI: Yeah, yeah. Jack Paar was all about how he felt, and what had he done that day, and what was irritating him. But he was like a raw nerve. You know, Jack Paar was amazing.

GROSS: So what year does he take it over?

UNIDENTIFIED ANNOUNCER: Jack Paar comes over in '57, and takes it over until '62.

GROSS: I want our listeners to hear a clip that you brought with you of a couple of guests on Jack Paar's "Tonight Show."

BIANCULLI: Oh, yeah. I'm so glad this exists, because it shows - you know, one of the things that Jack Paar was famous for was bringing on funny people, and just having them do things for him, you know, as his guests. But what he loved to do also was bring on a guest and then bring on another guest and have the mix. You know, that was a big core of his show.

And there's a show where it's Liberace and Muhammad Ali back when he was still Cassius Clay, very early in his career, and Jack Paar talks Liberace and Cassius Clay into doing a duet, and it was totally spontaneous.

GROSS: Are you sure of that?

BIANCULLI: Yes. I mean, they didn't know they were going to do it together. But, I mean, of course, Liberace can fake anything on the piano, and Cassius Clay, you know, just used one of his prepared pieces. He's like the world's first rapper out there, you know.

GROSS: Absolutely.

BIANCULLI: You know, but together they're great.

GROSS: Except rappers usually have beats behind them and not, like, really, like, frilly arpeggios and Liberace.

(LAUGHTER)

BIANCULLI: Yeah, not too many candelabras as bling.

GROSS: No, and I've just got to say, I watched David's clip. It's - before we play it, I just want to set the scene that Liberace's wearing one of his sequined jackets, and Cassius Clay is wearing this, like, beautiful suit.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: What a pair. OK, so...

BIANCULLI: The other thing is, there's no videotape in terms of you can't see these again the next day on YouTube. So this was one reason to stay up for Jack Paar, is because you either saw this sort of stuff, or you didn't.

GROSS: Good point. OK, so here's a dip into the past.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE TONIGHT SHOW")

JACK PAAR: Why don't you play for him? You'd rather play than fight with him, wouldn't you?

LIBERACE: Oh, that sounds - I'm a lover, not a fighter.

PAAR: Well, why don't you play and let Cassius - because if you don't - if you can't fight, you know, if it doesn't work out, you can always get a job with Burma Shave, I think, the way with this rhyming.

LIBERACE: Would you like me to play?

CASSIUS CLAY: Yeah, that would be a beautiful combination, Liberace and Cassius Clay.

LIBERACE: Move that way a little bit. You're standing in front of my candelabra. Well, you recite something, and I'll make up the music to it. For a change, do the one about you.

CLAY: This is the legend of Cassius Clay, the most beautiful fighter in the world today. He talks a great deal and brags indeedy of a muscular punch that's incredibly speedy. The fistic world was dull and weary. With a champ like Liston, had to be dreary. Then someone will color, someone with dash brought fight fans a-running with cash.

This brash young boxer is something to see, and the heavyweight championship is his destiny. This kid fights great. He's got speed and endurance. But if you sign to fight him, increase your insurance.

GROSS: That's really great. That's Cassius Clay, before he was Muhammad Ali, and Liberace with Jack Paar, when Jack Paar hosted "The Tonight Show." I just love it when Liberace says I'm a lover, not a fighter.

So how long did Jack Paar host "The Tonight Show"?

BIANCULLI: Jack Paar hosted it from '57 to '62, and then Johnny Carson took over for 30 years.

GROSS: Tell the story about how Jack Paar left, and how he left again.

BIANCULLI: Oh, "The Tonight Show" under Jack Paar used to be - once it went from, you know, live to pre-taped a few hours before, he told a joke one night, a water closet joke that I don't even need to go into here. It was not obscene or anything like that, but the network took umbrage and cut it out of his monologue and put a little news summary thing instead, and...

GROSS: So he used the word water closet and not bathroom?

BIANCULLI: Well, it was W - the whole joke was about there was a church in England and that there was a mistake between this chapel WC and water closet WC, and it was rules of what to do in each one, dumb series of jokes. But when they got cut, then Jack Parr was getting news reports the next day that he had said something that was improper, and he didn't want to have that reputation on him.

So he told NBC let me say the joke tonight, let them hear that it was OK because NBC apologized and said, well, we shouldn't have done it. And he goes, well, let me do it. And NBC said, well, no because then that makes it look like you're running the network.

So Jack Parr went on the show the next night, and during the pre-tape, he walked off his own show. He just said, you know, there must be a better way of making a living than this. And he walked off. And he stayed off for, you know, more than a month before they finally convinced him to come back. And when he did, boy, that was entertaining television.

GROSS: You have that clip with you.

BIANCULLI: I love this clip. Jack Parr's timing, his comic timing in coming back, it's just so good. I really hope you enjoy this.

GROSS: All right.

(SOUNDBITE OF TELEVISION SHOW, "THE TONIGHT SHOW")

(APPLAUSE)

JACK PARR: As I was saying before I was interrupted...

(LAUGHTER)

PARR: I believe my last words were that there must be a better way of making a living than this. Well, I have looked.

(LAUGHTER)

PARR: And there isn't.

GROSS: So that was Jack Parr returning after walking off of his own show, "The Tonight Show." How did he end up leaving for good?

BIANCULLI: He just decided that he was, after a certain number of years, starting to repeat himself and not liking it so much, and maybe it was time for a younger man to come in. And so he left, and there was this little hunt, and Johnny Carson got the job.

GROSS: I'll be back with our TV critic David Bianculli and a 1988 interview with Johnny Carson's longtime producer, Fred de Cordova, after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: It's late-night week on FRESH AIR. We're about to hear about "The Tonight Show" with Johnny Carson from its longtime producer. My partner on today's show is our TV critic David Bianculli. Carson really, like, owned "The Tonight Show" for so long. What were some of the late-night conventions that he created?

BIANCULLI: Well, whether he created them or not, he solidified them. So, the monologue, where it was where you came at the end of the day to find out what had happened that day and what Johnny's reaction to it was. You know, the monologue became important and sort of a national pulse.

The desk, there didn't always used to be a desk previously. Sometimes there were chairs, sometimes there were different setups. But it was the desk and the guests. The announcer was a holdover from Jack Parr's program, but Ed McMahon just stayed there forever. The house band, in terms of playing with the bandleader, another convention, and then all of the sketches.

Even if the stuff wasn't original to Johnny Carson, he made it his by dint of repetition and monopoly.

GROSS: Did he catch on right away?

BIANCULLI: Not right away but within a couple of months. He was actually nervous the first couple of weeks, and then he eased into it. But another thing to remember is he had no competition. So he really didn't have to lose as much as he had to just not, you know, go backwards. He was - and then by the time anybody thought of going up against him - I think the first significant one was Joey Bishop in 1967 - he'd already been there for five years, and he was already, you know, Johnny Carson.

GROSS: Well, I wish I could say at this point that now we're going to hear my interview with Johnny Carson, but as you can guess, I never interviewed Johnny Carson. But I did interview his longtime producer Fred de Cordova, who worked with him from 1970, I think, to when Carson left in '92.

BIANCULLI: He was there for decades.

GROSS: Yeah, and he was 60 when he got the job, which I found kind of surprising. And nice factoid about him, before becoming the producer of "The Tonight Show," one of the things he did was direct "Bedtime for Bonzo," the famous movie with Ronald Reagan.

BIANCULLI: Well there you go.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: OK, so here's my interview with Johnny Carson's "Tonight Show" producer Fred de Cordova, recorded in 1988, and I asked him where he sat during the tapings of "The Tonight Show."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED INTERVIEW)

FRED DE CORDOVA: Well, Johnny sits behind the desk that you've all seen often, and then there's the couch, and at the end of the couch in a chair, an uncomfortable chair, which gives me a perfect view of Johnny's eyes and vice versa, I am there about 12 feet away from his nibs.

GROSS: So you're really sitting very close.

CORDOVA: Right.

GROSS: Now you say in your book that you function as a sounding board when the going gets rough. Would you explain?

CORDOVA: Well, I think after all the years that Johnny and I have worked together, I have a pretty good read on his reactions to what's going on. And he sometimes looks at me for verification, like it's going well or not, and these are just little minor eye (Foreign language spoken). And I also have on my left, which is one of the most vital and compelling parts of television - a button - which means it's time to go to commercial.

And although most of the world loves to get up and go to the bathroom, it's my ability to get up and go over to Johnny and say this is going great, or why don't we go to the next guest.

GROSS: So when you press that button to go to a commercial, are you sometimes doing that to bail out of a tough spot?

CORDOVA: Yes, I think that's - let's not say a tough spot but one that isn't going quite as well as we hoped it would.

GROSS: Now you're making this all sound very calm and organized. I want to read a quote from what Robert Blake said to Kenneth Tynan for the Kenneth Tynan profile of Johnny Carson in The New Yorker some years ago. So this is Blake talking about what it's like to be a guest on "The Tonight Show."

He says: You better be good, or they'll go the commercial after two minutes. The producer, all the federales, are sitting like six feet away from that couch, and they're right on top of you, man, just watching you. And when they go to a break, they get on the phone, they talk upstairs, they to talk to Christ, who knows, they talk all over the place about how this person's going over, how that person's going over.

They whisper in John's ear. John gets on the phone and he talks. And you're sitting there watching, thinking what, are they going to hang somebody? And then when the camera comes back again, John will either ask you something else, or he'll say our next guest is.... It sounds crazy.

CORDOVA: Well, it's not - it's a little more controlled than that. There is a phone, me to the booth. There is no phone next to Johnny. We have to do evaluating and as you do in your business or anybody else, whether something is good enough or exciting - amuses Johnny and amuses the audience, those are our two goals, whether it's going well enough to go to the next guest or to say let's go a little longer with this man or woman.

And then there is also the terrible problem that if you go too long with a couple of your guests, you have to say that, oh, we're terribly sorry that so-and-so isn't with the show tonight, we hope we'll have time the next time. So you don't like to bump people, but that again is dependent on how much the audience and how much Johnny are being amused.

GROSS: Well, no guest gets on the show without your approval. What's the pecking order in terms of the lineup for the evening? How do you schedule what the lineup is?

CORDOVA: I think you try - if you go way back to vaudeville or even in a book, you try to mix your show so that there aren't all musicians, all authors, all camera freaks or all civilians. You try to mix it so that the audience, and we know it's a vast one, gets a little bit of each possible area of entertainment.

The normal running order would be the star, the comedian, the musician, and that goes sometimes in another area. We have...

GROSS: And then the book author, right?

(LAUGHTER)

CORDOVA: The book author is the bumpee, ordinarily.

(LAUGHTER)

CORDOVA: We've - I've bumped myself twice in the last two weeks.

GROSS: You know, I was wondering if you were going to go on and plug your book on the show.

CORDOVA: I certainly put my name up there, and since those guests are chosen by me, there that name was. But then the writers went on strike, and I've had to bump myself twice.

GROSS: No, you know, "The Tonight Show" has all these rituals that accompany it. I mean, the show opens exactly the same all the time, and it has for years and years. You know, Ed McMahon, if he's there, starts. He does the whole here's Johnny, does the whole hi-yo, and then, you know, bows to Carson.

And then there's the banter between Carson and the bandleader and Ed McMahon. Do you know how any of that started?

CORDOVA: Well, I was a young child at the time.

(LAUGHTER)

CORDOVA: But I believe it was, what, all - you want to acknowledge the fact that Johnny is there, that Ed is that person and that Doc is that person, and the band is available. I think you do what people - and I don't want to sound being psychologically involved with "The Tonight Show," but I do think that people have learned that "The Tonight Show" is what it has been the night before and the night before, not necessarily in the subject matter but that they, as they get into bed and turn out the light, ending that day, they see what they have seen and what they've enjoyed seeing for so long.

I also believe that the people, the shows that have tried to scramble the format, the talk variety format, are among the quickest to leave.

GROSS: Are there any shows that haunt you?

CORDOVA: No, and I think I can explain why, and not take too long in doing it. Our show is kind of like a baseball team in a baseball season. If you do one show a year or one show every three months or one show every four months, you have an awful lot of time to realize what a failure you've been.

But we do kind of a baseball season. We do a show one night, and then that we hope it's wonderful, and if not that, we hope it's good, and we hope it isn't bad. But even if it's a great show, or even if it's not such a good show, we do another show the next night, and we have no time, except in self-analysis to decide why it wasn't good or even why it was very good. We just do the next show and hope that that'll be a good one.

GROSS: My interview with Fred de Cordova was recorded in 1988. De Cordova died in 2001. Our late-night series continues in the second half of the show. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: Coming up, an interview with David Letterman, recorded in 1981. After his short-lived morning show was cancelled and before he took over "The Late Night" spot. Back then, he as best known as one of Johnny Carson's substitute hosts on "The Tonight Show." Our TV critic David Bianculli will play a clip from Letterman's first appearance on "The Tonight Show."

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR, I'm Terry Gross. It's late-night week on FRESH AIR. This week we'll be hearing from Jay Leno, Conan O'Brien, Jimmy Kimmel, Jimmy Fallon and Questlove, the leader of the band The Roots, which is moving with Fallon from "Late Night" to "The Tonight Show."

Coming up, we go deep into the FRESH AIR archive for a 1981 interview with David Letterman. But first, let's get back to my conversation with my partner on today's show, our TV critic, David Bianculli.

There are a lot of comics who became famous by doing their bit on "The Tonight Show" and a lot of comics who became even more famous by guest hosting...

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...for Johnny. Who were some of those people?

BIANCULLI: Well, the one who became the permanent guest host for a while was Joan Rivers and then eventually got her own show. Gary Shandling was another one who was very, very good at that. The big joke is that everybody hated it no matter who the guest host was most of the time because everybody wanted Johnny.

GROSS: Well, one of the people who substituted for Johnny Carson was David Letterman. And before we hear the interview with David Letterman, you brought with you a clip of Letterman on "The Tonight Show" because he is one of the people who got his start in terms of national fame...

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...by performing on "The Tonight Show." What did you bring with you?

BIANCULLI: This is a clip where you can tell how much the audience is responding to him the very first time and how he's taking his time, rather than being nervous. It's just his first clip on "The Tonight Show" and he has a routine about what his dog eats. And it's as simple but as easy to connect with as that.

GROSS: Here it is.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE TONIGHT SHOW")

DAVID LETTERMAN: ...was a Belgian airhead, beautiful animal. And a...

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: ...smart as a whip too. I'm feeding him that dog food, it's numbered. I'm not sure what it is but they got it for everything. One for the puppy, two for the middle dog, you know, three for the gay dog, four for the whatever, on up.

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: The site - I'm looking at this can and it says on there: for the dog that suffers constipation. You know, the way I look at it, if your dog is constipated, why screw up a good thing, huh?

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: Sure. So...

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: Sleep in in the morning. Let him bloat. What do you care?

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: So I'm buying the animal dog food and this one, I'm not sure the brand, but it says: all beef. Not a speck of cereal. Not a speck of cereal. It's a point of pride here. Not a speck of cereal. My dog spends his day rooting through garbage and drinking out of the toilet.

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: Chances are he's not going to mind a speck of cereal, you know?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That's David Letterman. His first appearance doing comedy on "The Tonight Show."

BIANCULLI: Yeah. I believe so. I think that '78 or '79.

GROSS: And it's still funny.

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And he still has the same kind of delivery. And you hear the laugh that he does, as people are laughing, he's laughing too. He still got that.

BIANCULLI: Yeah.

GROSS: That's great. He's like stayed himself.

BIANCULLI: But even the few seconds, just the little bit of space between the jokes. I mean, when you only have two or three minutes to score, to take the time to be at ease enough to enjoy the crowd enjoying the joke, I think that shows exactly why Letterman ended up being behind the desk himself.

GROSS: Let's talk about what Letterman brought to late-night because he started off doing the late night show.

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: You know, the late - what's it called? "Late Night with David Letterman."

BIANCULLI: "Late Night." Yeah.

GROSS: Yes. And it was after "The Tonight Show" and then he moved to another network.

(LAUGHTER)

BIANCULLI: Yes. Yeah. No. He...

GROSS: He's got the 11:30 slot.

BIANCULLI: Yeah. He started - if you think about that, he started "Late Night" in 1982, which means he's now been a late-night host longer than Johnny Carson was.

GROSS: Wow.

BIANCULLI: You know, for two different networks and two different shows.

GROSS: Yeah.

BIANCULLI: But he's been doing it for what, 31 years now.

GROSS: So what do he bring to late-night?

BIANCULLI: When he wants to, he can be a great interviewer and can also just be a genuine - what I call a genuine broadcaster, someone who can speak one-on-one as though the camera is just a friend.

GROSS: It's late-night week on FRESH AIR. I'll be back with our TV critic David Bianculli. And we'll hear my 1981 interview with David Letterman after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: It's late-night week on FRESH AIR. Before we hear my 1981 interview with David Letterman, let's get back to my conversation with our TV critic David Bianculli, my partner on today's show.

I think Letterman brought irony in a way that it hadn't been in late-night before. You know, like Johnny Carson told jokes.

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: He was funny. Steve Allen was very funny. But Letterman brought this kind of irony where a lot of things were in quotes. His relationship with Paul Schaffer was always, there was always irony there...

BIANCULLI: Do you remember...

GROSS: And a lot of pranks.

BIANCULLI: Yeah. You remember this syndicated show that Norman Lear did after "Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman" as a spinoff? It was "Fernwood Tonight."

GROSS: Absolutely.

BIANCULLI: Yeah. That's the show where all this irony really came from, where it's like we're putting on a show that we know is bad, that we now really isn't a show and we've got the conventions. And, you know, you had Fred Willard instead of Ed McMahon. You had Martin Mull instead of Johnny Carson. But they knew what they were doing. And Letterman sort of said well, OK, I can sort of mix these two things. And, of course, Gary Shandling did the same thing in a comedic context. But it's all look at turning it like a prism and saying, OK, Johnny Carson did it straight and you can't do it better than that but here's a little twisted way to do it. And I think Conan O'Brien was very big on twisting the conventions as well.

GROSS: So in 1981, when I spoke to him, the show, FRESH AIR was a local show in Philadelphia and he was performing at one of the local clubs. So he came to the studio and he was so not quite famous yet that he was sitting in our waiting room and like no one recognized him. People weren't going up and asking for autographs. And it was a really interesting place in Letterman's life, a time in his life because he had hosted a morning show...

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...before doing late-night. But it was a late-night sensibility but in the morning, which was really odd. And the show didn't last very long, it just lasted a few months. And he was so afraid that the show was going to get canceled before Christmas that he did his Christmas show in the fall.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And he was right. They canceled it before Christmas.

BIANCULLI: Yeah. Right.

GROSS: So this was just like a few months after that morning show was canceled and it was, I don't know, probably about a year before he took over the late-night spot. So an interesting place in his life. And one other thing I want to mention before we hear this is that our listeners will notice Letterman sounds kind of different than he does now speaking, and I certainly do.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So here's me and David Letterman, recorded in 1981.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED INTERVIEW)

GROSS: You sub frequently for Johnny Carson and the audience always seems so giddy during, you know, during a monologue. I wonder what the warm-up is like for "The Tonight Show" audience.

LETTERMAN: Well, the warm-up for "The Tonight Show" audience is the 19 years that that show has been on the air...

GROSS: Oh.

LETTERMAN: ...and has become part of American television and probably more typifies American TV than any other entity. And that's why it's that way. It's largely tourists and people who save their nickels and dimes and they're ready for an event. And if you see something going awry on "The Tonight Show," it is certainly never the fault of the audience because the audience will give you every benefit of the doubt. And I've lost a few battles, so I know what it's like. But they're always terrific.

GROSS: When you do one of those asides about how a joke's not working or something do you usually feel 'cause it's not?

LETTERMAN: Oh, sure. It's very difficult to do. Johnny Carson has made the monologue on "The Tonight Show" an art form and he does it better than anyone will ever do it. So by filling in for him, the comparison is always obvious and you always come up second best. Now the kind of material he does not after night after night is not the kind of material that a comedian necessarily develops for his act. They are two different kinds of things. He can come out and make jokes about the band. He can come out and make jokes about Burbank. And this sort of stuff is fine, but chances are it would not work to a random audience of folks in Las Vegas or Philadelphia or whatever. So when I started as a standup comedian, I developed that kind of material as opposed to "Tonight Show" kind of material. Now when you do "The Tonight Show," you suddenly have to find yourself coming up with just something that'll get by and it's always a very difficult task for me to assemble it.

GROSS: Well, how much do you come up with for your, you know, by yourself for the monologue and how much is done by writers?

LETTERMAN: It depends. I use some writers and it just depends. Sometimes the writers supply a lot if they are on a hot streak. And if not, you've paid several hundred dollars for typing paper. And the same is true with me. Sometimes, like the last time I had a funny idea was in the late '50s. So it's been a cold season for me.

GROSS: Is it on a teleprompter or anything? There's times I swear when not you, but Carson, when I could swear that I see him reading his jokes when he gets on there.

LETTERMAN: This is a way I do it. I'll show you here. I'm diagramming something for her. There is a art card. The dimensions of this would be roughly that way. And there would be, say I was going to do a joke about you. T-E-R-R-I?

GROSS: If it's a joke with a Y.

LETTERMAN: OK. Then I was going to do a joke about Philadelphia. So I've put Terry's name on top, then I put Philadelphia. Then say I was going to do a joke about my dog, I would put Bob. And that's what I work on. Just...

GROSS: So you just have our - the names there.

LETTERMAN: Yeah. And then I would have a gentleman hold that up for me and so on.

GROSS: What if you forget the joke?

LETTERMAN: Doesn't make any difference. It's just television.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: You had mentioned that Carson always can make jokes about the band and everything. One of your running gags on your show was, the band is cooking joke, in which they'd walk out with like shish kebabs and the piano and things.

LETTERMAN: Mm-hmm. It was and I'm not proud of that. From a humor standpoint it was...

GROSS: Why?

LETTERMAN: It was so stupid. I was proud that we did it. I was generally proud of the show because we'd try it once. And it was such a silly joke. It was just the lowest pun and we compounded it by doing it three or four times and - but it was fun. And that's the thing that I most proud of, is we created an atmosphere, I think, that where you'd really didn't - although, it was an allusion more than an atmosphere - where we're not sure what was going to do happen next. And so that was fun.

GROSS: Is there a generation gap between comedians? And I'm thinking about the kinds of comedians who make jokes like: hey, nowadays you can't tell the difference between the boys and the girls.

LETTERMAN: Mm-hmm.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And my wife, she's so stupid. And jokes like that.

LETTERMAN: Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: Well, there seems to be. But then again, I think there is an arena for each of those styles of comedy. And the people who are doing - it's very unusual, for example, to see a 19 or a 20-year-old guy doing jokes about my wife is so fat that when she sits around the house her head explodes - or whatever that joke is. But it's not unusual to see someone in their mid-60s still doing jokes about these kids today. And...

GROSS: Did any comedians from that school ever give you advice about, you know, how to polish your routine and what kind of jokes to include?

LETTERMAN: Well, there are certain of those guys and women that - see they - I think I do know what the difference is. Those people never had the benefit of working toward a media goal. They were working in cheap bars and Greyhound depots. There's certainly nothing wrong with Greyhound depots, but they had to work everywhere, and this is how they made their living. They had no hope of getting on "The Merv Griffin Show" because "The Merv Griffin Show" was not around. So if you wanted to be a comic, you did what would get you over under 99 percent of the conditions. And as a result, they selected the lowest common denominator.

Now, it's different. A comedian will - a guy thinks he's funny, he drops out of high school, moves to Los Angeles, prepares five minutes, appears on "The Merv Griffin Show" and thinks he'll get a situation comedy. And it's happened and it will continue to happen. So the gap I think is a result of the guys who began were doing it to survive. These were real fighters. They were in it for the long haul and they would do the kind of material that would quickly establish themselves as being funny and they couldn't sustain it and it could go on forever because they were really doing it for, you know, for a living. The other guys are looking to get into television situations, and I think maybe that's the difference.

GROSS: Did you ever have to write for comedians whose sensibility you didn't feel really in sync with?

LETTERMAN: The first, the gentleman I actually worked for was Jimmy Walker, who was a comic who was the star of a television show called "The Good Times," and who is black. And I think he may have been the first black person I ever saw. So it was difficult for me to - we would go to meetings and Jimmy was quite generous because I just moved from Los Angeles and had no money to speak of and he hired me to write with him and some other people, and it was funny. And sitting there pretending that I knew the first thing about what it's like to grow up in a ghetto situation was silly in itself. But it wasn't so much that our sensibilities were out of sync as it was he wanted personal anecdotes from his past to get his laughs with and it was tough for me to, you know, I had grown up in the middle of Indianapolis and, so that was interesting.

GROSS: Did you ever have to write for someone like Bob Hope who's probably always in search of young talent?

LETTERMAN: I did write for Bob Hope once. It was a wonderful experience. I wrote for a show that he was doing from Perth, Australia. And he had about a half a dozen writers, the mean age of whom I guess would be about 90. And Perth, Australia, in all the research that I did - and the producer of the show was actually an Australian.

And for three weeks everybody told me how great it was in Perth in the summertime because they said the beaches are the most spectacular places in the world and they're just covered with lovely women. So I was looking forward to going to Perth. Well, they took the three or four 90 year old writers who mentioned that they probably wouldn't be leaving the hotel room and left me back in L.A.

And I wrote and wrote for days and days and days, and never knew what became of the show. I was in Canada the night that it aired and I turned it on and actually heard Bob doing one of my jokes. And I thought, well, this is really a milestone, I have Bob Hope do a joke that I have written.

GROSS: What was the joke?

LETTERMAN: I don't remember. It was a Bob Hope joke, which I think was probably prefaced with: But I want to tell you. And I think may have ended up with: But, seriously, you know. And in between I'm not sure what the joke was.

GROSS: Who were your favorite comedians when you were becoming aware of comedy?

LETTERMAN: Well, there was a - you know, when I was really a young person I liked Jonathan Winters. He could just make me laugh under any circumstance. And Johnny Carson I thought was very funny. He used to do an afternoon show where he'd make fun of all odd manner of folks. Steve Allen, I thought was wonderful. I still think both of these guys are wonderful.

Richard Pryor at the time, I liked him and still like. The best person in a nightclub situation now is Bill Cosby. It's just unbelievable what this man is capable of doing. And he doesn't really tell jokes, per se, but he comes out on a stage and sits down in a chair and this is interesting because the purpose of your appearance here, you have to dominate this group. And to dominate and control from a seated position is interesting. And he does it.

And he is unbelievable. And I would guess he would be the best in a nightclub situation. And then there are, you know, the newer guys. Steve Martin is just a phenomenon. And, you know, it goes on and on. And then I have my own peers that I think are great. There's a guy, Jay Leno, who I think is probably the best new - not so new - but best at really observational material. And there's others, you know.

GROSS: Let me change the subject completely for a moment. I've always really admired your teeth because they are imperfect teeth and people are rarely allowed on TV unless they can do toothpaste commercials or something.

LETTERMAN: That's right. It's...

GROSS: And it's really distinctive to...

LETTERMAN: It's a federal code, actually. Your teeth have to meet certain minimum dental standards. Yeah. It was one of those deals where my parents, although not poor, did not have enough money - I don't know why I'm even telling this because it's just what happens in everybody's family. My sister had worse teeth than I and they thought, well, if we don't fix her teeth we're never going to unload her.

That sounds terrible. I don't mean it that way. But she was more conscious of her dental situation than I so they had her teeth fixed. Now, people who have never seen me probably think, gee, the man just must be - must look like a backhoe or something. I have spaces between my teeth and an overbite.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: OK. That's David Letterman recorded in 1981 when FRESH AIR was a local program in Philadelphia and David Letterman was in town to perform at a Philadelphia club. Do you have any thoughts listening back to how David Letterman sounded in '81?

BIANCULLI: Well, I love that he was so smart about the changes that were going on in the medium of television then, that the new comics could aim at something that a generation before, it didn't even exist. And that also he's talking about comedians shooting for getting sitcoms. And this is - he' saying it three years before Bill Cosby, whom he just said great things about, got "The Cosby Show."

And then after that, you know, there's "Roseanne" and there's just about every comic on television got on television with a sitcom. So he was ahead of that curve.

GROSS: It's Late Night week on FRESH AIR. I'll be back with our TV critic David Bianculli after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: It's Late Night week on FRESH AIR. My partner on today's show is our TV critic David Bianculli who just listened back with us to my 1981 interview with David Letterman. One of the things David Letterman brought to late night television was irony, but you brought a clip with you of the broadcast - the first broadcast that he did after 9/11. And of course, as everyone knows, he broadcasts from New York.

And he was still really shaken up when he returned. And it was not a night for irony. And do you want to introduce this clip, David?

BIANCULLI: Yeah. He was not only - it was his first night back, but it was anybody's first night back out of New York. And he was just talking. And as honestly as somebody at that moment, I think, could have.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "LATE SHOW WITH DAVID LETTERMAN")

LETTERMAN: Welcome to the "Late Show." This is our first show on the air since New York and Washington were attacked. And I need to ask your patience and indulgence here because I want to say a few things and, believe me, sadly, I'm not going to be saying anything new. And in the past week others have said what I will be saying tonight far more eloquently than I'm equipped to do.

But if we are going to continue to do shows, I just need to hear myself talk for a couple of minutes. And so that's what I'm going to do here. It's terribly sad here in New York City. We've lost 5,000 fellow New Yorkers and you can feel it. You can feel it. You can see it. It's terribly sad. Terribly, terribly sad. And watching all of this, I wasn't sure that I should be doing a television show.

Because for 20 years we've been in the city making fun of everything, making fun of the city, making fun of my hair. Making fun of Paul, well...

(LAUGHTER)

LETTERMAN: So to come to this circumstance that is so desperately sad - and I don't trust my judgment in matters like this, but I'll tell you the reason that I am doing a show. And the reason I am back to work is because of Mayor Giuliani. Very early on after the attack - and how strange does it sound to invoke that phrase, after the attack? - Mayor Giuliani encouraged us, and here lately, implored us to go back to our lives, go on living.

GROSS: That was David Letterman recorded on his first broadcast after 9/11. And this was, you know, he was already doing the 11:30 CBS show.

BIANCULLI: Mm-hmm. Yes.

GROSS: And it's just nice to be reminded that when the time comes to be really sober he does it very well.

BIANCULLI: Yeah. And I think it's also good to remind ourselves we're losing this. The idea - the whole idea of broadcasting, people watching these shows at the same time and it meaning something, whether it's the comedy of a Johnny Carson monologue or the seriousness of David Letterman doing that, the newest generation of late night hosts, they're making their impact with viral videos, with little pieces.

People aren't really watching the shows in anywhere near the numbers they used to.

GROSS: Well, David, before you go, since this is the first day of FRESH AIR's Late Night week, just give us a quite chronology to remind us of some of the permutations in the history of late night television.

BIANCULLI: OK. Well, you've got basically the "Tonight Shows" with start with Steve Allen, then Jack Parr, then Johnny Carson. And then you have that whole mess where it goes to Jay Leno instead of Letterman and then it goes to Conan and then back to Leno. And we're going to have another change next year.

That's the "Tonight Show." That's the key one. But the interlopers, there were so many that went up against Johnny. Dick Cavett was probably the best of them over the decades. But there was Pat Sajak. Near the end there was Joan Rivers. There was - oh, my god, there was Chevy Chase for, like, seven or nine weeks of terrible stuff.

And then you had Jimmy Kimmel coming on to ABC and doing some really good things. You had - later at night you had Tom Snyder, you had Craig Ferguson, two more solid pure broadcasters, I think, in what they were doing. And then Jimmy Fallon and, you know, we're going to have next year Seth Meyers joining the mix.

GROSS: So let me just put you on the spot. Favorite late night host ever?

BIANCULLI: Jack Parr, oddly enough, I think for me because he was so incredibly unpredictable. I think Johnny Carson is the king of late night. Ferguson is the most pure in terms of being a broadcaster. I think Jimmy Fallon is the most talented and Jimmy Kimmel may have the quickest comedy mind. That may change when Seth Meyers shows up. But they each have something. They're all doing something interesting.

GROSS: Well, David, I want to thank you so much for helping us begin our Late Night week on FRESH AIR. David Bianculli is FRESH AIR's TV critic. Can you come back and be with us again tomorrow?

BIANCULLI: Oh, sure.

GROSS: Terrific. Here's what we have coming up for you later this week. On our Late Night week we have interviews with Jay Leno, Conan O'Brien, Jimmy Kimmel, Jimmy Fallon, and QuestLove. So it's going to be a really fun week. I hope you can be with us for it.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: You can download podcasts of our show on our website freshair.npr.org. And you can follow us on Twitter at nprfreshair. Our blog is on Tumblr at nprfreshair.tumblr.com.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.