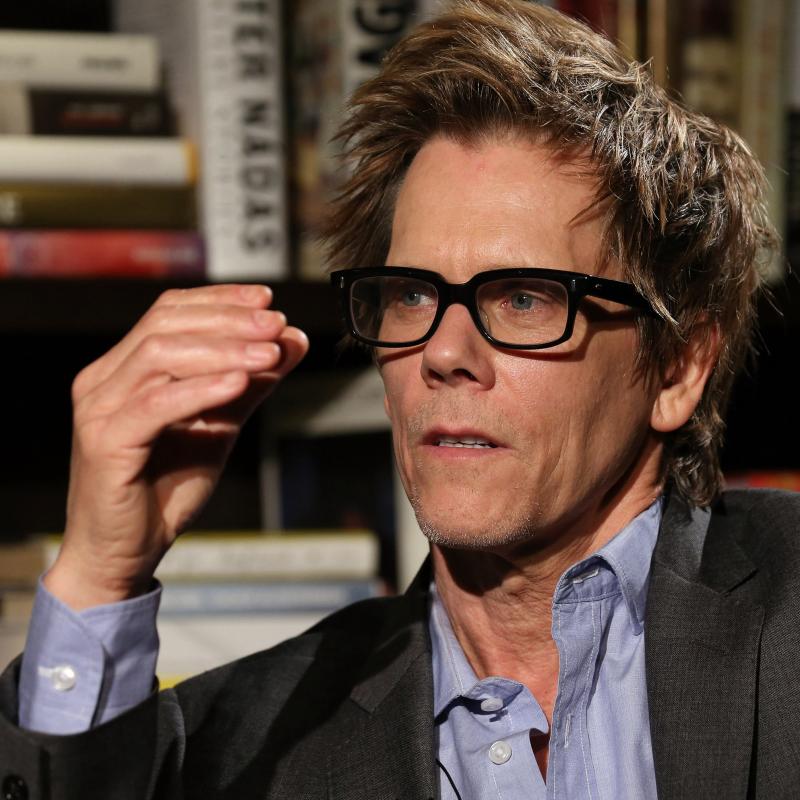

Kevin Bacon's Serious Turn

In the new film, The Woodsman, Kevin Bacon plays a sex offender just released from prison. Bacon was first recognized in the 1982 film Diner, and went on to roles in Mystic River, A Few Good Men, Flatliners, and Footloose. He's made over 50 films and inspired the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon game, in which players try to link another actor with Bacon in as few steps as possible. He is married to the actress Kyra Sedgwick, who also co-stars in The Woodsman.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on January 18, 2005

Transcript

DATE January 18, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Kevin Bacon discusses his career and his latest film,

"The Woodsman"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Kevin Bacon, is starring in the new movie "The Woodsman." He plays

a sex offender who has just gotten out of prison after serving 12 years for

molesting young girls. The movie follows him as he tries to re-enter society

and keep control of his own impulses. New York Times film critic A.O. Scott

described Bacon as giving `a complex, unsettling performance, a reminder of

the power of screen acting to illuminate even the darkest of souls and to

bring us closer to people we might otherwise do everything possible to avoid.'

Bacon got his start in movies like "Footloose" and "Diner." He's since

starred in many films, including "Apollo 13," "Murder in the First," "The

River Wild" and "Mystic River." We're going to look back on some of his roles

a little later. Let's start with a short scene from "The Woodsman." Bacon's

character, Walter, is meeting with his psychiatrist and has confided that he

just followed a young girl in a shopping mall, but he didn't touch her or talk

with her.

(Soundbite of "The Woodsman")

Unidentified Man: What did you think would happen?

Mr. KEVIN BACON: (As Walter) I don't know.

Unidentified Man: What did you want to happen?

Mr. BACON: (As Walter) I don't know. Would you please stop writing on the

(censored) pad? You know that if anything happens to me, I go back to prison,

no parole, no nothing, for life.

Unidentified Man: Is this the first one?

Mr. BACON: (As Walter) Of course it is. Why do you think I'm telling you?

Unidentified Man: I want you to calm down. You followed a girl. Perhaps you

wanted to see what it felt like after so many years. Maybe subconsciously you

were testing yourself, and here you are, talking about it with me. This is

positive. Walter, we'll pick up here next week.

Mr. BACON: (As Walter) Remember when you asked me what my idea of normal was?

Normal is when I can see a girl, be near a girl, even talk to a girl and not

think about--that's my idea of normal.

GROSS: I asked Kevin Bacon about preparing for his role in "The Woodsman."

Mr. BACON: You know, I didn't spend time hanging out with child molesters. I

did do a lot of reading and a lot of research. There's a lot of research that

the director had done about people that have this affliction, but it was

important for me to make him an Everyman, because one of the things that's

most frightening about this, you know, sickness is that it cuts across all

kind of, you know, racial, socioeconomic, even international boundaries. You

cannot look at a crowd of people and pick out the sex offender. So it was

important for me to make Walter an Everyman.

GROSS: Now you're dealing with a character who knows his impulses are wrong.

He understands that. But knowing that they're wrong doesn't make them any

less strong. And so throughout the movie, your character is fighting his

impulses, and even, you know, whether he's in an area where there's a child in

sight or not, he's keeping himself in check and that's constantly registering

on your face. It's a very kind of withdrawn, introverted performance, because

you're always--you're--aside from couple of moments, you're always holding

back and holding it in. Can you talk a little bit about doing that?

Mr. BACON: I think that the driving force for me is shame. He's a very

shameful character, and I think that all of us have things in our life that we

can feel ashamed of. You know, you have to go to work and take that shame and

put it in your gut every day and make sure that you keep staying in touch with

it and hope that it comes out through your eyes. I think that you have to--it

has to be there in any kind of situation.

For instance, if I look on the schedule and I see that there's a day where I'm

just riding the bus all day, normally in a movie, you go, `That's going to be

an easy day,' you know? I don't have to beat anybody up, I don't have to cry,

I don't have to, you know, yell and scream, you know. I'm just riding on the

bus. But they're all hard, 'cause it's a day--he's riding on the bus with a

lot of shame, you know. It's got to be there all the time in everything that

he does, walks and talks and, you know, sits there and eats a bowl of cereal,

you know.

I felt really strongly that I wanted Walter to be a person that we would see

how he was feeling rather than hear how he was feeling. There are--just like

in life, there's people who are more verbose or demonstrative and wear their

heart on their sleeve, you know? Walter is someone who has tried to

disappear. He spent 12 years in prison and to be a child molester in prison

is the lowest person on the totem pole and it would make someone want to hide.

GROSS: The one character in the movie who is really kind of sympathetic

towards you and understanding of you is a woman who you work with, who is

played by your real wife, Kyra Sedgwick. And I'm wondering if it's--what it's

like to work with someone who you actually know really intimately, and you

have to be in this acting situation where you're getting to know each other.

Of course, the people you're getting to know aren't who you really are. But

no one knows you better than a spouse, so is it harder to establish these

characters who are mysteries to each other?

Mr. BACON: Well, it's a difficult acting exercise because you have to erase

16 years of marriage of 16 years of familiarity. So often as actors we're

asked to do the exact opposite. I can't tell you how many times I've met

somebody, you know, at 6:30 in the morning in the makeup trailer, and they

say, `OK, this is--she's playing your mother.'

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BACON: And then 15 hour--half an hour later you're on the set, and you

have to bring everything, all the complexities of that relationship through

this complete stranger you have no relationship with at all and no history

with. It's difficult. And this is like the opposite problem where you have

to kind of erase the history.

GROSS: And what happens when the movie's over? You know, I hear so much from

actors that it's hard sometimes to shake a character. That might be

particularly true when you're playing a pedophile like you are in "The

Woodsman," and then you go home with the main character who you're acting

opposite, who is your wife, and so if you stayed in character at all when you

got home, or if the roles kind of came home with you, that would really be a

problem.

Mr. BACON: Yeah. Well, I can say that people have sort of looked sometimes

mistakenly at the idea of the two of us working together, that it would

somehow make the process easier for either one of us emotionally, and it's

just--it couldn't be farther from the truth. I mean, the fact is that when

you have two people that are actors, in our case what we tend to do is I'll go

to work and she becomes kind of a support system, you know, for me, in terms

of taking care of the kids and the house and being a shoulder to cry on. Then

she goes to work and I take over that job, and I become the support system for

her. When we're both working together, we're really not there so much for

each other as husband and wife, and so it is difficult.

In terms of leaving it at home, you know, I did a movie called "Murder in the

First" where I was playing this prisoner and I was getting beaten and

shackled, and I was covered in bugs and dirt, and I had lost a whole bunch of

weight and was in a very, very dark space emotionally, a similar kind of space

to where I was when I was doing "The Woodsman." But I have this picture of me

about two days after I wrapped the picture, and I'm on a beach in Hawaii. My

head's shaved and I'm still gaunt and pale, but I'm holding my little girl and

you can see on my face that that guy is behind me, that it couldn't be farther

from my thoughts. So it's not so much that I carry it over as it is I know

that I have to go back into that place the next morning. That's the thing

that's difficult, not leaving it behind, but knowing what's ahead of you. So

on Friday night, you know, when you wrap on a Friday night, you know, you have

a beer. You know that Monday morning, I gotta be Walter again, and so it

makes the weekend, you know, a little bit rough.

GROSS: Kevin Bacon is my guest, and he's starring in the new movie "The

Woodsman," in which he plays a child molester.

Do you prefer child molester or pedophile in the context of your character?

Mr. BACON: I prefer sex offender.

GROSS: Sex offender, because he was locked up, so he's officially an

offender?

Mr. BACON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And why do you choose that over pedophile or child molester?

Mr. BACON: Well, I think that it's a difficult subject matter and it's a

difficult movie to want to get people to see. However, people are amazed at

what they feel about the movie, and the reactions that we've gotten as we've

traveled all over the world and all over the country and done countless

screenings have been incredibly positive. And I just think that `child

molester' and `pedophile' are two words that are even more repulsive, you

know, in some ways, and I mean, I think it's one of the things that I've tried

to put out there as much as possible, and you don't go to this movie and run

the risk of seeing bad things happen to children. As disturbing as the film

is, and as tense as the film is, it's not--there's nothing in it that is

gratuitous or sensationalized.

GROSS: My guest is Kevin Bacon. He's starring in "The Woodsman." We'll talk

more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Kevin Bacon. He's starring in the new film "The

Woodsman." Let's hear a scene from his 2003 movie "Mystic River." He played

a state trooper investigating the murder of a young woman who was the daughter

of his childhood friend. In this scene, he's questioning a couple of the

girl's friends.

(Soundbite of "Mystic River")

Mr. BACON: (As Sean) You guys were having a goodbye dinner, right?

Unidentified Woman #1: What?

Mr. BACON: (As Sean) Well, she was leaving town, wasn't she, going to Las

Vegas?

Unidentified Woman #2: How do you know?

Mr. BACON: (As Sean) She closed her bank account, she had hotel phone

numbers.

Unidentified Woman #2: She wanted out of this dump. She wanted to start a

new life.

Mr. BACON: (As Sean) Well, a 19-year-old girl doesn't go to Las Vegas alone,

so who was she going with? Come on, girls. Who was she going with?

Unidentified Woman #1: Brendan.

Mr. BACON: (As Sean) Excuse me?

Unidentified Woman #1: Brendan.

Mr. BACON: (As Sean) Brendan Harris?

Unidentified Woman #1: Brendan Harris, yeah.

GROSS: Now "Mystic River" was directed by Clint Eastwood. I just saw him on

the "Actors Studio" on Bravo, the series in which he's--of interviews with

actors and directors, and he said in his interview that he likes to have a

very quiet set and that some actors--some directors like to holler `Action!'

but he likes to say, `OK, let's start the scene now,' or just doesn't...

Mr. BACON: (Imitating Clint Eastwood) `OK, you guys, go ahead.'

GROSS: Yeah, OK. Is that what it was like?

Mr. BACON: That's what he says, yeah. Then he says--and when he says cut, he

goes, (imitating Eastwood), `That's enough of that.'

GROSS: Does that work for you, to not have like the clanging--what do you

call it, the...

Mr. BACON: Slate.

GROSS: The slate, the clanging slate and to not have somebody crying

`Action'?

Mr. BACON: Well...

GROSS: Did it make a difference?

Mr. BACON: It makes a huge difference. You know, a long time ago, actually

when I was working with John Hughes, I came to the realization that part of

what--part of the setup for movies is to create this very, very tense time

between `Action' and `Cut,' which is the time when things should be the most

relaxed. It's when an actor should be the most relaxed. And you know, what

happens is, you've been thinking as an actor all day about what you're going

to do, and someone pounds on your door and gives you a 10-minute warning, and

then they give you a five-minute warning. Then they say, `OK, we're ready for

you.' You're already getting nervous, like you're going to jump out of a

helicopter, you know, into the Mekong delta or something.

And now you're on the set and people start screaming, `Quiet! Quiet! Cell

phones off! Quiet! Rolling! Speed! Marker!' The sound guy's usually so

far away that he's screaming, you know, when he's got speed on the knocker,

and then the guy hits the slate, and you're like a deer in the headlights.

And now you gotta act. And then you say, `Cut!' and all the tension goes out

of the room, and everyone's on the phone and they're talking about lunch and

dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah.

When Clint was doing television, Westerns, he realized that he'd get six

horses lined up, and they would start screaming and they'd hit the slate, and

the horses would all take off. And he figured that if that was true for

horses, it's gotta be the same for actors. So he has no open walkie-talkies,

and the camera assistant just barely taps the slate. He doesn't say,

`Action.' So instead of jumping into some kind of acting head, you just are

kind of there and you just inhabit the scene, and then you inhabit your way

out of the scene, and you do another take, and it becomes the actor's time as

opposed to--you know, we only have these 10-second bits that are about us.

And it's very, very helpful and very, very powerful.

GROSS: Is he a non-intrusive director in other ways, too?

Mr. BACON: He's very non-intrusive, yeah. You know, he does not rehearse.

He doesn't give you, you know, long kind of suggestions about your character.

You know, I was playing a state trooper and I had to go out and, you know,

find some state troopers to ride around with. You know, it's not like, you

know, he demanded that of me. I'd worked on a Boston dialect that I worked on

by myself. There was no machine in place to, you know, kind of take care of

that.

GROSS: Should there have been one?

Mr. BACON: No. I mean, I feel like you--I like to do my own homework, you

know. I come to the set having made very clear decisions. I'll ask a

director for suggestions if I feel like I need them, and I'm certainly willing

to hear them or, you know, I'm open to any kind of input, but, you know, I

also want to go away and figure out who my guy is and come ready to go. And I

think all of us kind of knew that was the drill with Clint. And so all of us

came wearing our game jerseys and, you know, we were ready to step up to the

plate. That's sort of what you want to do for him, you know. And that works

really well for me, because I don't discover my character in the course

of--between, you know, take two and take 25, you know. I know who he is and I

also don't want to talk about it that much. Do you know what I mean? I don't

need to discuss it, and...

GROSS: Does it make it too schematic if you do?

Mr. BACON: Well, I think it can--I don't know. I think it can get in the

way. You know, that's not to say that there aren't directors that I've worked

with that have been helpful, but honestly there haven't been many times where

someone has come over--and this is--I think, generally the public's perception

of the great director is the guy who comes over and whispers some gem of a

piece of information in the actor's ear and all of a sudden, you know, they're

"Sophie's Choice," you know what I mean? You know, I think that's not usually

the case.

GROSS: Can you pinpoint a time where you realized you were no longer, like,

the teen star or the new young star, that you were established and you were,

like, a full-fledged adult not only in person but in terms of the kind of

roles you were going to get?

Mr. BACON: Well, now I can't really pinpoint a time. I mean, I think it's

kind of a process. I mean, there have been moments in my career that have

felt like a turning point. Certainly, you know, "Footloose," you know,

obviously changed kind of the landscape for me in a way that I was not really

all that comfortable with, frankly. I mean, I was kind of--I thought I was

ready for it, but I really wasn't, and in a lot of ways I sort of rejected

that kind of stardom. And all of a sudden I didn't really want to be on

magazines, and I didn't really want to, you know, sign autographs and...

GROSS: But why not? Everybody--so many actors seem to really want--in

addition to good roles, they want the fame.

Mr. BACON: Well, I know. I have to say that I always have said that there's

two kinds of actors, actors that want to be famous and liars. You don't go

into this business because you want to fade into the background.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BACON: That's not the nature of an actor. It was just that that kind of

pop stardom is not the kind of stardom that I was looking for. I wanted to

be, you know, a legitimate New York, you know, actor, you know. I don't know.

GROSS: Admired for the craft and the dramatic roles...

Mr. BACON: Right, like...

GROSS: ...not, like, `He's cute! He's cute!' Yeah.

Mr. BACON: Exactly. Exactly. Exactly. And now I was, you know, on the

cover of whatever, Tiger Beat, you know, that kind of stuff.

GROSS: Right. Right.

Mr. BACON: So I rejected that in my own way and was kind of spinning my

wheels for a long time, many years. A lot of movies that I believed in that

didn't pan out, and then, you know, I'd sort of go into independent films and

smaller films, and they weren't seeming to break out and, you know, doing some

plays. But "JFK" was a movie that really turned things around for me, because

I worked for four days on the movie, and it was a very extreme

characterization of this kind of fascist, gay sociopath, and I--the movie came

out and the phone started to ring. It started to lead the way to much more

serious and complex and kind of edgier sort of stuff, and it was a great

turning point for me.

GROSS: Kevin Bacon is starring in the new film "The Woodsman." He'll be back

in the second half of the show. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of "Footloose")

Mr. KENNY LOGGINS: (Singing) Now I gotta cut loose, footloose. Kick off your

Sunday shoes.

GROSS: Coming up, getting the lead in "Footloose," then finding out he has to

dance in it. We continue our conversation with Kevin Bacon. And Maureen

Corrigan reviews Pete Hamill's new book "Downtown: My Manhattan."

(Soundbite of "Footloose")

Mr. LOGGINS: (Singing) Come on before we crack. Lose your blues. Everybody

cut footloose. You're playing so cool. Obeying every rule. Dig way down

into your heart. You're burning, yearning for some, somebody to tell you that

life ain't passing you by. I'm trying to tell you, it will if you don't even

try. You can fly if you'd only cut loose, footloose. Kick off your Sunday

shoes. Oo-wee, Marie. Shake it, shake it for me. Oh, Milo, come on, come on

let's go. Lose your blues. Everybody cut footloose.

Backup Singers: Cut footloose. Cut footloose.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Kevin Bacon. He's

starring in the new film "The Woodsman." Let's hear a scene from his 1984

film "Footloose," which helped make him a star. He played a city boy who

moves with his family to small town, where rock music and public dancing are

banned. In this scene Bacon's character, Ren McCormack, is asking the town

council to allow his high school to have a dance. The minister has strongly

opposed the idea. Ren decides to beat him at his own game by turning to the

Bible.

(Soundbite of "Footloose")

Mr. BACON: (As Ren McCormack) And it was King David--King David--who we read

about in Samuel. And what did David do? What did David do? What did David

do?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. BACON: (As Ren McCormack) David danced before the Lord with all his

might, leaping--leaping and dancing before the Lord; leaping and dancing.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BACON: (As Ren McCormack) And Ecclesiastes assures us that there is a

time to every purpose under heaven, a time to laugh and a time to weep, a time

to mourn. And there is a time to dance.

GROSS: Let me ask you about "Footloose." The role that you played was so

different, I think, than who you were and what your life had been. You grew

up in the city. This is about a kid who, you know, moves to a small town.

You know, the preacher hates dancing and frivolity, and you, of course, teach

the kids how to dance, and you have to dance in it. And it's such a teen

film. And you'd been, I think, like, the youngest actor in Circle in the

Square, a kind of long-respected theater company in Greenwich Village. I

mean, the sensibilities seem, like, so different. Did you feel like you were

cast in a movie that was almost alien to what you knew?

Mr. BACON: Well, I mean, first off, I was about 23, I think, or 24 when I

did the movie.

GROSS: Which is about five years older than your character?

Mr. BACON: Yeah, yeah. So playing a high school kid, you know, was a little

bit difficult for me. I felt like I was so kind of beyond high school in my

mind, and I'd been living essentially on my own since I was 17. So it was,

you know--yeah, there was something that was kind of alien about it. I didn't

really even realize that it was a dance movie. I figured that I would just

dance, you know. And then all of a sudden I saw that there were

choreographers and dance doubles and all this kind of stuff.

GROSS: They didn't audition your dancing?

Mr. BACON: They did, but it was just kind of like a class. I just took a

class, and they watched me do this dance class. I had no idea that it was

really a dance movie per se. But I said to Herb Ross that--I said, `You don't

really need a choreographer, man. You can just turn on the music, I love to

dance. I'll just dance around for you.' You know, I didn't get it.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. BACON: I didn't get it. But all that being said, you know, I took the

character very seriously. I thought about him as, you know, coming from a big

city and what it would be like to be in a small town and to feel alien to this

environment. And, you know, I did all the same work that I would do for

anything else. In fact, I went--I got the local high school in Provo, Utah,

which is a very heavily Mormon community, to enroll me as an exchange student.

And I was concerned--I wanted to see if they would think I looked too old

because I was very concerned about playing someone 17. And I also wanted to

see what it would feel like to be an outsider. Although I had done soaps and

I'd done "Diner," nobody recognized me. And the teachers, in fact, didn't

know--were not in on the scam. It was just the principal of the school and I

think maybe the guidance counselor or something. They introduced me as Ren

McCormack and...

GROSS: That's your name in the movie.

Mr. BACON: Yeah, and that I was, you know, just like the kid--and it was

actually very, very helpful and interesting; terrifying, in a lot of ways,

you know. I had big guys, you know, threatening to beat me up and girls...

GROSS: Seriously?

Mr. BACON: Yeah. And girls, like, you know, giggling and laughing and, you

know--I mean, just--it was very much like the movie. And one kid sort of

befriended me, you know, and took me around. And I remember that in the--I

think in the script I was going to go to school, and the mother said to me,

`If you're going to go to school, you have to put a tie on.' And I said, `No,

Mom, I'm not going to wear a tie.' And I knew that that was crazy, that kids

in high school didn't wear ties, so that wasn't something I needed to--so we

kind of switched it around and I put the tie on. She says, `You're not going

to wear that tie, are you?' And when I went to the school, you know, these

kids were all farmers and, you know, jocks and dressed accordingly. And I had

sort of like a, you know, punk kind of hairdo and a skinny tie and, you know,

kind of a funky-looking jacket and stuff like that. And I remember just them

looking at me like I was a freak.

GROSS: You know, when you're in a movie, your face is blown up on a big

screen, you're on the cover of magazines, and you have to look at yourself

because I'm sure you have to watch some of the rushes or the movies, if for no

other reason than to analyze your performance and see how you did. Does that

experience--for you, has that experience made you any more or less physically

self-conscious? And I don't know if you're prone to self-consciousness or not

in the first place. Some people are, some people aren't.

Mr. BACON: Well, let me first say that if you ever left your outgoing

message and then played it back and you just cringe, you multiply that by

about a thousand, and that's what it's like watching yourself on a movie

screen because it's not just your voice. It's your face, it's your eyes, it's

your hair, you know, it's your body. It's very hard to look at yourself in

that kind of way.

I have spent a lot of time looking at rushes. I started on "Footloose," and

Herb Ross was very resistant of letting me, as most directors are actually

very resistant to letting their actors see their dailies. In fact, I put it

in my contract now so that I don't have to have an argument with the director

over this. And he finally let me in to, you know, see dailies. And I was,

you know, kind of horrified. And I figured that what I needed to do was learn

how to get past that and to watch enough footage, so that if there was

something that I wanted to play, I could learn how to play it, you know. And

I could learn things about camera and learn things about camera angles and

what plays and what doesn't because a lot of times as an actor you think

you're doing something, then you see it, and it doesn't come across that way.

You go, `God I could've sworn I was playing it like this, and it's just not

that at all.' I prefer to have some kind of control over that. I don't want

to just kind throw myself out there and let it turn into whatever it turns

into. So I watched and I watched and I watched and I watched . And it did

make me, to a certain extent, numb to seeing myself and hearing myself.

GROSS: My guest is Kevin Bacon. He's starring in the new movie "The

Woodsman." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Kevin Bacon, and he's starring in the new movie "The

Woodsman," in which he plays a sex offender.

You grew up in Philadelphia.

Mr. BACON: Yes.

GROSS: And your father, Edmund Bacon, is a very important person in the city

of Philadelphia, and I live in Philly, so I can say that with some authority.

I think he was the head of the Planning Commission for several years.

Mr. BACON: Yeah.

GROSS: He designed part of the Center City of Philadelphia, and there's even

a street named after him now. And, you know, I interviewed him several times

when I first got here in the '70s. I'm wondering how it affected your

connection to the city of Philadelphia when you were growing up, knowing that

your father designed part of it and that his sensibility was an integral part

of your environment.

Mr. BACON: Yeah, that's true, but that's not something that necessarily you

think about all the time when you're a kid. I mean, my dad used to take me on

walks and say, `OK, this is going to be'--he called them field trips. You

know, `This area used to be, you know, whatever, burned down. Now there's

houses here, and we're going to put a greenway through here,' yeah. I think

that certainly, as a kid, I was proud of him, and there was an element of

celebrity that he had in Philadelphia--and still has--that I probably aspire

to. And it was, in some ways, formulative to me because, you know, I think a

lot of boys want to beat their father, and, you know, in a way I think I

wanted to beat him at the fame game, you know. But...

GROSS: Check, accomplished?

Mr. BACON: Yeah, but not in Philadelphia, though.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. BACON: It's still, `Hey, Ed, Ed, Ed, Ed.' But, you know, that wasn't

really a part of my day-to-day life. I mean, I was--whatever--going to school

and hanging out with my friends. And the interesting thing is also that my

mother, while she lived here with my father, was a New Yorker. And I think

that in her own kind of subtle ways, she used to talk to us a lot about New

York and how magical it was for her when she was a little girl. And, you

know, out of six of us, there's three of us there now. So...

GROSS: You didn't go to college. You, after high school, moved to New York,

so that you could join the Circle in the Square School. And that's a theater

and school in New York.

Mr. BACON: Yeah, it's an acting school. It's a--well, I was in a two-year

program, and I stayed for a year and then started working.

GROSS: Did your parents approve of that, or did they think you should go to a

school where you'd get your BA?

Mr. BACON: No. My parents had, you know, five kids before me, and they were

all around two years apart, and eight, nine years later, you know, I was born.

I think they'd pretty much seen it all and done it all and, you know, kind

of--I think their attitude was, you know, `Whatever you want to do, you know,

you'll be all right.' And I was a very, very independent kid. I mean, I

remember from earliest memories thinking to myself, `I gotta get out of here

and start making my own money and start living on my own, and I don't need

help.'

Came my senior year in high school and I hadn't really applied to any

colleges, and no one had really noticed, and I was able to get out of high

school half a year early because of, you know, doing some accelerated thing.

And I was working in a book-packing warehouse, and I was going to do a play

here in Philadelphia for the bicentennial. It was kind of like a--we were

sort of getting together with this group to, I don't know, kind of write this

musical. And it didn't feel like it was going in a good direction, and I

heard about a summer program with Circle in the Square. So I went up and

auditioned for that. And I was too young to go to their professional

workshop, but I begged them if they would just let--consider me 'cause I think

most of the kids were out of college. And they said, `OK, you know, we'll let

you audition.' I had the audition, I got in. My dad gave me tuition and some

money to, you know, look for an apartment, and that was it; I was off to the

races. And they never said anything about, `You need to go to college to have

something to fall back on.' It wasn't even discussed.

GROSS: Were you the youngest kid in the school?

Mr. BACON: Yes.

GROSS: Was that a good thing, a bad thing?

Mr. BACON: It was good.

GROSS: Why?

Mr. BACON: I'm not sure why, but I think it was good (laughs).

GROSS: It must have been comfortable in the sense you'd been the youngest kid

at home.

Mr. BACON: I'd been the youngest kid at home. I'd been...

GROSS: It was a role you were familiar with.

Mr. BACON: Yeah. I'd been the youngest kid at home. I was working in a bar

where I was by far the youngest person who was in the bar hanging out. When I

was younger, I had--almost all of my relationships with women were with women

15, 20 years older than me, and it was just what felt right to me. I don't

know.

GROSS: First film was "Animal House." Would you describe your role in it?

Mr. BACON: I was a frat boy from the bad guys, the preppy kind of fraternity

in the movie. They're sort of like the jerks, the elite fraternity.

GROSS: And what was it like to be on the set? Did you hang out with Belushi?

Did you have fun and meet people you wanted to? Did you feel like an

outsider?

Mr. BACON: Well, it was my first movie, and, I mean, I was so overwhelmed by

the process and seeing what actually went in to make a movie. And here I was,

and I was living in a hotel. And they had this thing called per diem, where

they just give you cash every week. And there was a lot of kids 'cause we

were on a campus, so there was, you know, fraternities and girls. And, I

mean, it was kind of great, like, in that way. But there was also this

dividing line that happened off camera between the actual guys who were in the

"Animal House" and those who weren't, and they had a great sort of fraternity

kind of thing going on that was very much like the movie and very exclusive.

Belushi wasn't so much a part of that because he was actually shooting for a

few days and then flying back and doing "Saturday Night Live" and then getting

back on a plane and shooting for a few days and going back. You know, we were

out in Oregon, so it was a long, crazy kind of trip for him back and forth

from the set. Yeah, I mean, I did feel quite a bit like an outsider.

And then when the movie opened, I was working; I was back waiting tables, you

know. I mean, I took my money after--you know, came back to New York feeling

like a movie star, and I spent all my money in about a week or two weeks

and...

GROSS: I know there are so many actors, particularly in New York and probably

also in LA, who are there taking the order, and you know that they're

thinking, `I'm not really a waiter. I'm an actor.'

Mr. BACON: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you go through that?

Mr. BACON: Well, yes and no. I mean, the restaurant that I worked at, it was

an unusual place in that it was not like a real service kind of establishment.

It was a place where regulars would go for a shot and a beer and a hamburger.

And if you were expecting to, you know, get some ass-kissing, you were in the

wrong place. And the boss really looked out for the staff, and we looked

after each other. And it was kind of like my first family away from home.

You know, it was a family of cops and pimps and drunks and, you know, Wall

Street bankers and doctors and lawyers. And you know what I mean? It was a

very kind of diverse group.

GROSS: Oh, it sounds great. You were lucky.

My guest is Kevin Bacon.

I hope you don't mind my asking this, but when was the first time--'cause

you're probably tired of talking about it--when was the first time you found

out about the existence of the game Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon?

Mr. BACON: I don't remember the first time, but I do remember that, you know,

it was a long time ago. I mean, it's been around a really long time...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BACON: ...at least 10 years, 15 years. I don't know. And people would

say to me, `I played this drinking game the other day, and, you know, you had

to take a shot--booze--every time for every degree of separation from you.'

GROSS: I didn't know that was part of it.

Mr. BACON: Yeah. Or they said, `Yeah, a friend of mine's cousin came up with

a game about you,' you know--I mean, a lot of very, like, diverse kind of

things. And then it was one of the first things that really spread on the

Internet, you know. It was really the beginning of the In--I'm not saying the

game started the Internet, but when the Internet really started to begin, we

weren't used to these kind of concepts that exponentially, you know, would

spread. And Six Degrees was like that. People started talking about it and

playing it.

It was actually started by these guys down in--it was the University of

Virginia or something like that. They were sitting around in their college

dorm room and came up with this concept. A movie of mine was on the TV. And

Jon Stewart used to have a show--yeah, a nighttime show, and he had those guys

on. And, you know, I remember going to the show with my publicist, and it was

like, `OK, you know, I hope you're not too freaked out about this, but those

guys that, you know, say they came up with the game are, you know, going to be

on there.' And I thought it was a joke at my expense; that's the way I

perceived it being, you know, having a bout of low self-esteem, you know. I

felt, `Well, they're'--the ideas that, you know, they say, `Can you believe

that this jackass can be connected to Marlon Brando or, you know, Laurence

Olivier,' or something like that, you know. `Isn't that ironic?' I thought

that was kind of the joke. When I actually met the guys, they were--that

wasn't true. I mean, they actually were, you know, fans of the movies and

stuff like that. So...

GROSS: One more question. What else do you have in the works now?

Mr. BACON: Well, I have a picture called "Loverboy" that I directed that

Kyra is also in, and it's a book that we optioned and developed a screenplay

and...

GROSS: By who?

Mr. BACON: It's by Victoria Redel. It's a story of a woman and her

six-year-old son, and she has this very, very obsessive kind of relationship

with him and is trying to create this sort of utopian world for the two of

them to live in. And the little boy eventually wants to step out and make

friends and go to school, and we come to find out that she's emotionally

incapable of letting that happen. And we're going to premiere it at Sundance

in about a week. So that'll be nerve-wracking. And then I have "Beauty Shop"

with Queen Latifah; it's coming out in April. And I did a picture called

"Where The Truth Lies" with Atom Egoyan, who's a great Canadian filmmaker, and

Colin Firth is my co-star in that one.

GROSS: Well, great. I'll look forward to seeing those. Thank you so much.

Mr. BACON: Thank you.

GROSS: Kevin Bacon is starring in the new movie "The Woodsman."

Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews Pete Hamill's new book, "Downtown: My

Manhattan." This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Pete Hamill's new book, "Downtown: My Manhattan"

TERRY GROSS, host:

Many of Pete Hamill's devoted readers think that if New York City could speak,

it would sound like Hamill. In his latest book, "Downtown," Hamill reflects

on the city that's given him his best subjects and his distinctive voice.

Book critic Maureen Corrigan has a review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN reporting:

When Pete Hamill is on, I don't think there's a writer in his field to touch

him. A few weeks ago he wrote an essay for The New York Times on the deaths

of actor Jerry Orbach and writer Susan Sontag. And somehow within the

thousand-word or so constraints of that essay, he evoked telling aspects of

their characters and nailed a certain kind of glancing intimacy that New York

offers with people who, as he wrote, `on the surface, are not like you.'

Hamill's forte is nostalgic non-fiction, whether the piece in question is,

like that eulogy, personal journalism or his great autobiography, "A Drinking

Life," or the meditation on Ol' Blue Eyes he wrote a few years ago called "Why

Sinatra Matters." The novels of his that I've read slip slide into bathos.

His elegiac non-fiction knows when to put on the brakes.

Hamill's latest work of non-fiction, "Downtown," is something of a literary

dream date. Match one of our greatest chroniclers of times past with the city

in which he's generated his memories, and you've got a match made in heaven

or, more precisely, made somewhere in the vicinity of 14th Street. In

"Downtown," Hamill takes readers on a walking tour through the part of New

York that he calls home, the part where, throughout his adult life, he's

literally paid rent at 14 separate addresses. Hamill defines his downtown

idiosyncratically. For him, it extends from the Battery all the way up Times

Square.

His ramble sprawls out in time, too. As anyone who's lived in New York for

even a brief space knows, the city is haunted. There are those street names

that summon up the shades of vanished orchards and Dutch settlers. There are

those quintessential New York personalities, like Stanford White, Charlie

Parker, Walter Winchell, Allen Ginsberg and Joey Ramone, who've passed on but

left their trace in what Hamill calls `the city's human alloy.' And there are

the buildings, most of all the buildings, some that have mutated throughout

the decades from robber barons' mansions into Gap stores, while others, like

the New York World Building, the old Penn Station and, above all in this

ethereal skyline, the twin towers that have simply disappeared.

In Hamill's reading of the city, New Yorkers resemble the Dubliners of James

Joyce's immortal short stories. They rush among these ghosts but don't always

understand the signs and wonders of their presence. Indeed, for a native like

me, some of the fun of reading Hamill's book lies in learning the deeper

significance of mundane sights. That red star on the Macy's shopping bag, who

knew that it derived from a tattoo that its 19th century founder, Rowland

Hussey Macy, got when he went to sea at 15? Truth to tell, though, any

cultural historian of middling ability could excavate such epiphanies. The

singular pleasure of Hamill's book is his voice, as suited to this subject as

Sinatra's was to, well, the singing of "New York, New York." Hamill says

that, `As a city, New York's characteristic tone is one of tough nostalgia,

tough because among the many codes spoken and unspoken by the generation of

immigrants who largely make up New York is the one that absolutely forbids

self-pity.'

Surely Hamill must realize that in characterizing New York's distinctive tone,

he's perfectly described his own. When Hamill really hits his stride here, in

the second half of the book that wanders up Fifth Avenue, through Union

Square and down and around The Village, his descriptions and anecdotes are the

tonal equivalent of an Irish wake. They strike just the right balance between

mournfulness and rueful humor. Take this tossed off reminiscence: `I still

go to Abe Lebewohl's Second Avenue Deli, where I used to sit over blintzes or

kasheh varnishkes with Paul O'Dwyer, the tough, laughing, white-haired

defender of almost everybody who needed defense. He was one of the last in a

line of passionate Irish lawyers that started with Thomas Addis Emmet in the

early 19th century. Every time he walked into the Second Avenue Deli, he was

embraced by the owner, the waiters and half the customers. The other half

were from out of town.' That's tough nostalgia for you distilled into a

paragraph toasted with a shmeer. You can't get anything quite like it outside

of New York. And inside of New York, you can't find anybody who does it

better than Pete Hamill.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She

reviewed "Downtown: My Manhattan" by Pete Hamill.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.