Hugh Laurie's 'House': No Pain, No Gain.

For the past eight seasons, the English actor has played Dr. Gregory House on the Fox medical series. During that time, Laurie's character has diagnosed dozens of patients suffering from rare ailments, while maintaining a serious addiction to Vicodin.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on April 25, 2012

Transcript

April 25, 2012

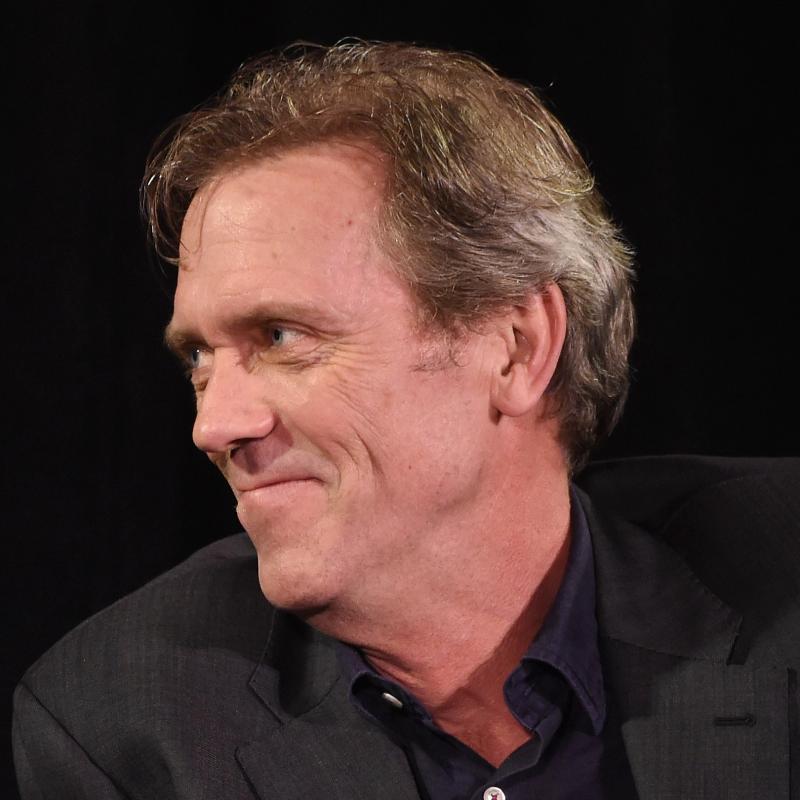

Guest: Hugh Laurie

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. After eight seasons, the medical mystery series "House" will show its final episode May 21st. My guest is the star, Hugh Laurie. He directed the episode that will be shown next Monday. Laurie is a British actor who first became known to Americans for his work in the British comedy series "Black Adder" and "Jeeves and Wooster."

As Dr. Gregory House, Laurie plays a brilliant diagnostician who consults on the most mysterious cases at a teaching hospital in Princeton, New Jersey. The doctors and patients pay a big price for his genius: House is abrasive and condescending. His own medical problem is unsolvable. He's in constant leg pain, and walks with a cane. It's led to serious problems with a dependency on Vicodin.

At the heart of each episode of "House" is a patient stricken with a mysterious, life-threatening problem which is misdiagnosed until House figures out the cause. Some of the cases are comic, like this one from the 2004 series premiere, when House was sent to diagnose a man at the hospital clinic who had turned orange. Here's the patient.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "HOUSE")

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) I was playing golf, and my cleats got stuck. I mean, it hurt a little, but I kept playing. The next morning, I could barely stand up. Well, you're smiling, so I take it that means this isn't serious. What's that? What are you doing?

HUGH LAURIE: (As Gregory House) Painkillers.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) Oh, for you, for your leg.

LAURIE: (As House) No, because they're yummy. You want one? It'll make your back feel better. Unfortunately, you have a deeper problem. Your wife is having an affair.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) What?

LAURIE: (As House) You're orange, you moron. It's one thing for you not to notice, but your wife hasn't picked up on the fact that her husband has changed color. She's just not paying attention. By the way, do you consume just a ridiculous amount of carrots and mega-dose vitamins? Carrots turn you yellow. The niacin turns you red. Find some finger-paint and do the math, and get a good lawyer.

GROSS: In this season's premiere episode, House was in prison for having driven his car into the home of the woman who had just left him, his boss Dr. Lisa Cuddy. But even in prison, he's diagnosing a mysterious illness. A fellow inmate seems to have had an allergic reaction that left him unable to breathe until House performed an on-the-spot, unauthorized tracheotomy. In this scene, House has finagled his way into the prison clinic to see the patient after figuring out the cause was not a food allergy.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "HOUSE")

LAURIE: (As House) It wasn't the food. It was the heat. It's mastocytosis. It can be set off by hot liquids, like the coffee he just drank.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) Masto is usually a skin disease.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: (As character) Usually? It can hit any organ: joint pain, osteopenia, and anaphylaxis, eyebrow loss. It fits.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) It's a possibility. I'll run some blood tests. Thank you.

LAURIE: (As House) No, no. It's almost impossible to confirm masto with blood work. Just give him five aspirin.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) If he has masto, he'll go into anaphylactic shock and won't be able to breathe again.

LAURIE: (As House) You do understand the meaning of the word confirm?

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) I'll do it. I almost died in that cell.

(As character) House, you're in here because you think you can do whatever you want, whenever you want. You can't, and neither can I. The ACLU would have my job, my license, maybe even my house if I do an unauthorized experiment...

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: (As character) Yeah, but if it is masto...

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) It's not.

LAURIE: (As House) Well, then, what do you have to lose by giving him the aspirin?

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) I'm not taking the risk.

LAURIE: (As House) It's his risk to take. If he has another attack and there isn't a doctor in the next cell, he could die. So for one second, will you stop covering your ass and do the test?

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: (As character) I think House is right.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) No.

LAURIE: (As House) You're a moron and a coward. I'll do it myself.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: (As character) Guard. You're done here, just like every other place you've ever set foot in your life.

GROSS: Hugh Laurie, welcome to FRESH AIR. I love that even in prison...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: ...you're treating patients and calling people morons.

LAURIE: I am calling people morons wherever I can, yes.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So it's going to be weird - I'm sure everybody tells you this in America. It's going to be weird hearing you in your own voice, because I'm so used to you as House, with the American accent. The first time I heard you in your own voice, I just - I couldn't believe it.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: Well, thank you. I suppose that's a good thing, but yes, I am - I'm not playing House today, so I am dressed as an Englishman, speaking as an Englishman. I'm wearing a bowler hat, if anyone's interested, and carrying a frilled umbrella.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: Yes, it is - it's nice to have a day every now and then.

GROSS: So if you wanted to do this interview in American - and I'm not suggesting that you do that - could you do that? Do you know American well enough to just improvise your way through it?

LAURIE: Yes, I think I do, but I have - I have to have all sorts of emergency backup plans. If I see a word coming along that I know I can't do well, I have to find an alternative very, very quickly. I read the other day that people - stammerers, people who stutter and stammer, have the same - have to have the same mechanism, where they see a problematic word hoving(ph) into view, and they have to line up three or four alternatives to go to if it doesn't come out right the first time. And I have to do the same thing if I'm just sort of ad-libbing.

GROSS: Are there certain words that you know will trip you up in American?

LAURIE: Yes, I can't say New York. So, I don't go there.

GROSS: Because I would say it New York, with an N-O-O, as opposed to N-Y-O-O.

LAURIE: Yes, I don't know if it's the New or the York, or the two of them together. I don't know what it is, but it just scares me silly. So I can't say it, and I don't go there. Murder I can't say, and I don't do it. I tend to avoid murder. What are other ones? Court orders. I don't issue them or receive them because they also scare me silly.

I suppose it's R's. R's are the problematic letters. But I do find there is - I can't think of a single word or even a syllable that really comes out the same in English and American.

GROSS: You directed the episode of "House" that will be shown next week. It's the second time you've directed an episode. Why did you want to direct it?

LAURIE: Well, it's - directing is the best job going. I don't really understand why everybody doesn't want to direct. It's an absolutely fascinating combination of skills required and puzzles set on every possible level, emotional and practical and technical. It calls upon such a wide variety of skills. I find it completely absorbing. And the only thing that had held me back was that I - it obviously - there's a worry that it compromises my ability to do my main job, which is to play the role of House.

GROSS: So do you direct yourself any differently than other directors do? Is there anything you're going to be doing under your own direction that is different?

LAURIE: No. Well, usually, I suppose I, as an actor, then pay the price of getting behind on time. Whereas I might demand of another director, I don't feel - I feel as if I need more time to do this again and again and again. When I'm directing and I've got to have an eye on the clock, I won't give myself that time. I'll see if I can get it right once or maybe twice, and then we have to move on because I need - I want to devote time elsewhere. So I'm sort of shortchanging myself, in a way.

But I also do - I defer to others. You know, if I'm doing a scene with Robert Sean Leonard - he's a man I would put my life in his hands, and almost have on occasion. And I would say to him, you know, did that seem all right to you, and he will definitely say not quite, or he'll say yes. You know, that was great. You've got it. So, you know, I'm - I defer to others around me. They're a fantastic bunch of people, and I trust them completely.

GROSS: So, "House" is ending at the end of this season. Why is it ending, and did you have a vote in that?

LAURIE: Yes, I did have a vote, although it never really came to that, you know, the paper, scissors, stone moment. It was a sort of consensus that we had run our course. And it occurred to me the other day that I suppose one of the problems is that the character is so inherently self-destructive, to the point of being virtually suicidal.

A person cannot be a character - a fictional character cannot sustain that suicidal tension indefinitely. You can't have a man on a window ledge threatening to jump forever. At some point, he's either got to jump or get back into the building because the crowd below, who are either urging him to jump or not jump, eventually will lose interest.

And I think that - because the tension must dissipate, eventually. And in actual fact, at the point we're going to leave the show, at the moment, it's to be or not to be. It's House deciding whether to embrace life or death. But having made that decision - and I won't tell you what that decision is - having made it, I think it's time for us to move on. I think that's - it is the right time.

GROSS: Wow. So House is either going to take his life, or be resigned to life as he knows it, and maybe even cheer up.

LAURIE: Oh, have I said too much?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Nah, he's not going to cheer up.

LAURIE: Right. Well, cheering up, I don't know. He's obviously - there are some obstacles to that. But, you know, all things are relative. There's a relatively cheerful House. I've always enjoyed the sort of playfulness of the character. I've always found that there is - there is a playful child in there somewhere, for all his cynicism and sarcasm. I think there is a child there who delights in silly wordplay and pranks and practical jokes and things...

GROSS: Making people squirm.

LAURIE: Yes.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: And, you know, it's sometimes obnoxious, but it's sort of - I find it quite endearing sometimes. In someone of such manifest intelligence, so obviously gifted, that to see someone behaving in such a plainly childish fashion I find rather endearing.

GROSS: So you've spent the better part of the last eight years playing someone in constant physical pain, and the pain has affected how you walk, with a limp and a cane. It's affected your personality, which is just kind of bitter, cynical, grudging, resentful. So let's talk about that for a moment. Did you feel like you needed to really understand the exact nature of House's injury, know exactly what movements would increase the pain and exactly how severe the pain was in order to play it?

LAURIE: I did the best that I could. I think pain is a very - it's an extremely hard thing to empathize moment to moment. And you often don't remember your own pain, you know, that moment that you broke a limb or you burned yourself or, I think, this is a common thing that women talk about with childbirth, that the memory of the pain is hard to summon up and relive, thankfully.

But then, of course, that very quickly has to take the backseat to the more pressing demands of how do you stage a scene, what is the best thing for a scene. And sometimes, you know, it has just been necessary for House to be more nimble than other times. It is just dramatically more important that he can skip over that desk with a certain amount of agility and brio, never mind the fact that he's obviously dragging a severely damaged leg with him.

So it's a strange - it's a constant mixture of things from moment to moment, trying to make a judgment about what is believable, what is an accurate presentation of this, the pain that he's suffering, but also what actually plays a scene in the best possible way.

GROSS: What impact has it had on your spine and your leg to walk with a limp so much?

LAURIE: I am horribly, horribly damaged, and let that be my opening statement in a massive lawsuit, which I am plotting. But my sport of choice when I was a young man was rowing, or crew as I think you call it over here, and I always - I rowed with the oar on one side, on the stroke side, which meant my body was twisting in the same direction many, many thousands of times a day, under stress for about 15 years.

And I think that's given me a permanent sort of kink. I do remember, though, the first time I did an acting - I had an acting engagement outside of "House," it was actually - it was a film called "Street Kings." And the first scene I did, oddly enough, was set in a hospital. And the director called action, and I started limping.

And I think that's a bigger problem for me now, is that I just have a Pavlovian response to cameras. If I see a camera, or if someone says action, I will start limping.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: I don't think I'll be able to walk straight now...

GROSS: I just hope you have a good chiropractor to undo favoring one leg for so long.

LAURIE: Yes, and they've got their work cut out for them, I think.

GROSS: My guest is Hugh Laurie, the star of the medical mystery series "House," which will show its final episode May 21st. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Hugh Laurie, who stars in the series "House." And this is the last season, and next week's episode is directed by Hugh Laurie, as well as starring him. So you wrote a novel in 1996 called "The Gun Seller," and there's a paragraph all about pain that I want you to read for us. And you have that paragraph with you, right?

LAURIE: I do. I travel with my novel with me.

GROSS: We faxed it to you, yes. We did fax it to you.

LAURIE: I don't, I don't carry my own novel around with me. That would be obnoxious, I think.

GROSS: Just in case. And I should say here, just to set it up, that there's a really large man in this section who is trying to break your arm, and he's trying to do it really, really slowly to increase the length of pain and the intensity of your pain.

LAURIE: (Reading) A one-armed combat instructor called Cliff - yes, I know, he taught unarmed combat, and he only had one arm, very occasionally life is like that - once told me that pain was a thing you did to yourself. Other people did things to you. They hit you or stabbed you or tried to break your arm, but pain was of your own making.

(Reading) Therefore, said Cliff, who'd spent two weeks in Japan and so felt entitled to unload manure of this sort of his eager charges, it was always within your power to stop your own pain. Cliff was killed in a pub brawl three months later by a 55-year-old widow, so I don't suppose I'll ever have a change to set him straight. Pain is an event. It happens to you, and you deal with it in whatever way you can.

GROSS: So that's Hugh Laurie reading from his 1996 novel "The Gun Seller." You know, reading that and thinking about how much pain House is in all the time made me wonder, like, what's the worst physical pain you ever experienced?

LAURIE: When I was about, I think, 10 years old, I made a petrol bomb. Well, I thought of it then, a friend - there were two of us, and we thought of it at the time as a Molotov cocktail. That sounded so exotic and exciting. And it went wrong, and I got burning petrol on myself and burnt my leg quite badly. And my father, who was a doctor, and he treated me - he treated me, it was one of those rare times.

He was massively unsympathetic because I think he was so furious at the idea that I'd been playing with burning petrol, and it's a fair point. And I kept - I can remember sort of yelling at the top of my voice, it hurts, it hurts. And he said yes, it will, and that was a lesson learned.

I think that was the most extreme pain I've been - burns are - well, as is commonly known, burns can generate quite extraordinary degrees of pain, and that was the worst that I can remember.

Then there are other kinds of pain. I suppose the pain of rowing, I think, which is something you deliberately submit to, you try and load upon yourself, because the more you can endure, the further ahead of your opponent you'll get. That would probably come second in my litany of pain.

GROSS: Did being a rower help teach you how to put pain aside and just focus on what you wanted to do?

LAURIE: I don't know. Maybe it did, or maybe I already had that sort of slightly masochistic caste of mind, and therefore that suited me to the sport because I do - I can remember at school, I used to sit in class, and just to while away an idle hour, I would induce cramp in my - I still to this day can do it. I can induce cramp in my feet and legs - just to see how long I could stand it. I don't know why. That's rather odd, isn't it?

GROSS: That is really, really odd. Cramps in feet and legs are so uncomfortable.

LAURIE: Yes, well, I can and do induce it.

GROSS: You still do that?

LAURIE: I do.

GROSS: Wow, that's really weird, if you don't mind my saying.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: No, it is a bit weird, yes. It is. And sometimes, if there's a bucket of ice about - and occasionally in life there is. If I see a bucket of ice, I'm quite tempted to give it a go and see if I can put a stopwatch on it. I am a bit twisted, as I mentioned earlier. But I'm sure it'll all be all right in the end.

GROSS: Because House is in constant pain, he's had really bad problems with Vicodin addiction. Did you do research on Vicodin and the long-term effects it would have?

LAURIE: I did research into the short-term effects, which were very pleasurable. And by the way, this was not within the borders of the United States. I'm just making that perfectly plain. But I took it for recreational purposes - well, that's to say, I was not in pain when I took it. So that counts, I suppose, as recreational. And the effects on the body are quite different if you're not actually suffering pain, so I understand.

It's just a sort of pleasant, wafty feeling, extremely pleasant, and I can imagine highly addictive. But it's quite different, I think, if you're suffering extreme pain, and you take it for analgesic reasons. I think it behaves quite differently. And, of course, its long-term effects, I obviously couldn't research that without doing serious damage to my internal organs. So...

GROSS: There's always the Internet.

LAURIE: Although I love my craft, I don't love it that much. There is, yes, and there are many stories to be told. But it is obviously a very serious problem in his life, and many people's lives. I mean, it is alarmingly easy for people to stumble into a dependence on painkillers, you know, from the most trivial surgical procedures. Somebody might take a couple of pills, and then their life is never the same again.

GROSS: Hugh Laurie will be back in the second half of the show. He stars in the serious "House" and directed next week's episode. There's just a few episodes left. The serious concludes May 21st. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with Hugh Laurie, the star of the medical mystery series "House," which will show its final episode May 21st. Hugh Laurie directed next week's episode. As Dr. Gregory House, Laurie portrays a brilliant diagnostician at a hospital who deals with patients who will die unless he can figure out the cause of their mysterious problems.

Your father is a doctor, or I'm actually not sure if he's still...

LAURIE: He's not still alive. No. And he was a doctor. Yes.

GROSS: He was a doctor.

LAURIE: Yeah.

GROSS: So he passed before "House"?

LAURIE: Yes.

GROSS: Do you think about him when you play House, because you grew up with a genuine doctor?

LAURIE: Many times. Many times. I think - well, first of all, with great affection obviously, but also I think my father gave me, bequeathed to me a great reverence for medical science. He was about as opposite to the personality of House as one could imagine. He was the most polite and gentle and easygoing of men, and would have gone to great lengths to make his patients feel attended to and heard and sympathized with. And he probably would have been somewhat horrified at House's behavior, but at the same time he had a sort of steely honesty about medical and psychological truth, that there are certain things - one must be humble in the face of facts. And he was not someone who would allow sentiment to cloud an issue.

And if a truth had to be spoken, he would speak it. And he would, I think he would've approved of House's scientific courage, if not his social skills. I think he would've approved of some elements of House. As I think a lot of doctors do, actually. I think some, of course, feel that House has given them a bad name, but most I think feel, well, yes, actually, those are on occasion things that we have wanted to say or felt but cannot say because we are constrained by, you know, the possibility of lawsuits or being punched in the face or whatever it might be. But sometimes patients can drive you absolutely insane with the way that they withhold information or they won't take medication that you've given them or they won't follow their instructions, and that sort of thing.

GROSS: So what was your audition like when you were auditioning to play House?

LAURIE: Well, it's one of the very rare times I've actually got a role from auditioning. I'm not a good auditioner. But this was a role I did, I knew - even though I only had a couple of scenes, I felt that there was something in this, something very substantial in this and I wanted to do it well and I worked very hard at it. And I came to Los Angeles and I booked into a hotel room and I paced up and down in that hotel room for a couple of days just doing these two scenes over and over and over and over and adjusting, because I was determined that this was not going to be one of those auditions where I walked out and smacked my forehead and said, oh dammit, why did I do it like that? I wanted to do - I wanted to do what I wanted to do and at least leave and say, well, that's how I think it should be and if they don't like that, then that's their business but at least I did what I wanted to do. So I tried to buy a cane. You can't, of course, buy a cane in Los Angeles because there are intimations of mortality there, and a cane's...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: Oddly enough, you can buy an umbrella, which you would think would be even less appropriate in Los Angeles, but that I did buy. I bought an umbrella and used it as a cane and I hobbled up and down in my hotel room for days and days, until I knew that no matter how scared I was, they couldn't - I couldn't be beaten out of doing it the way I wanted to do it. I rehearsed myself into the ground, as it were.

GROSS: So, you know, I've been listening to your voice. We started off talking about how surprising it was the first time I heard you with your own British voice. You know, we're so used to hearing you on "House" with an American accent. But, you know, as you've spoken, one of the things I've noticed about your voice is that I think it's like, it's higher than House's voice and House's voice tends to get more trapped in his throat than your voice. Can you talk about working up the voice for House and did you do that in the audition?

LAURIE: I think I did in the audition - although I noticed that there was a very different tone in the clips you played that were separated by eight years, I think. Well, the voice arrived sort of as a consequence of my attempt to relax. The great trap for non-American actors trying to play Americans, I think, is to start thinking of American-ness as a characteristic. It isn't. It is no more a character trait than height. It is just a physical fact and that's all there is to it. It says nothing about the psychology of a character, and you therefore have to not let it overpower the character and walk - you know, I'm going to walk around in an American way. That's obviously absurd. So my most deliberate and conscious effort was to relax and not push the accent, and the consequence of that was that I think it went down in pitch, not because I wanted it to go down in pitch but I think when I stopped pushing it, the accent, it just sort of came out that way, and pretty soon I was sort of stuck with it. It varies a bit as the show varies a lot, I think. One of the things I've always loved about "House" is that it skips through tones very quickly and, you know, one's voice has to follow that to a degree.

GROSS: So you know, with House, the way you do House's voice, it's, you know, it's as if a lot of his dialogue was muttered under his breath or said between clenched teeth, you know, said as an aside, even when it's not really an aside. But sometimes it is an aside, it's just a very sarcastic aside that everybody hears...

LAURIE: Right.

GROSS: ...because he's saying it loud enough for everybody. But - so is that intentional on your part? And can you talk about like placing your voice and maybe demonstrate that a little bit?

LAURIE: Well, it's, of course it's a sort of a dance you do with the sound recordist. You have to know that the sound recordist is working on the same - well, literally the same wavelength as your radio transmitter, but also on a sort of artistic wavelength. They're very, very good at what they do and it's a good partnership. They have to know how you're going to place your voice and the two of you are really working together.

GROSS: But just in terms of lowering your voice and making it a little like more in your throat for the part.

LAURIE: Well, I suppose when I'm really relaxing and not trying to - actually, really is one of the words - is one of my sort of warm-up American words because it has an R and L's. And R and L's are the, those are the two, the twin demons for anyone trying to do an American accent.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: And yes, when I start to do that, the only way I can do it is to just completely let my throat go floppy and sort of wind up down here. I don't know why. But I suppose - but it somehow seemed appropriate for House. I felt it was right. I felt that he had a sort of confidence, a physical confidence and a physical command that would mean that he never needed to be shrill in any way. I was actually thinking the other day that in eight years and 180 shows that we've done, I can only think of about four occasions when House actually deliberately raised his voice. There was nothing shrill about him. He has a sort of physical confidence and a physical - he occupies a physical space in a very - in a very firm, firm and confident way.

GROSS: My guest is Hugh Laurie, the star of the medical mystery series "House," which will show its final episode May 21st. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Hugh Laurie, the star of "House." And next week he directs the episode.

So let's talk a little bit about your British comedy. In the late '80s, I think it was the late '80s, you did a series called "Blackadder," which is a comedy, and each season was a different historical period.

LAURIE: Yeah.

GROSS: So I want to play a clip from "Blackadder." This is a scene in which you're the Prince Regent, so you're like heir to the throne. And Blackadder at this point is your butler, played by Rowan Atkinson. And you're really dressed like I think a fop, is the right period word to use here.

LAURIE: Yes.

GROSS: You've got like a powdered wig, the cape. You're kind of like the man about town, or at least want to be seen that way. And so here's the scene.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SERIES, "BLACKADDER")

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Ah, Blackadder, notice anything unusual?

ROWAN ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) Yes, sir. It's 11:30 in the morning and you're moving about.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) Is the bed on fire?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Well, I wouldn't know. I've been out all night. Guess what I've been doing. Waaaaaahh!

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) Beagling, sir?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Better even than that. Sink me, Blackadder, if I haven't just had the most wonderful evening of my life.

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) Tell me all, sir.

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Well, as you know, when I set out I looked divine. At the party, as I passed, all eyes turned.

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) And I daresay, quite a few stomachs.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Well, that's right. And then these two ravishing beauties came up to me and whispered in my ear that they loved me.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) And what happened after you woke up, sir?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) This was no dream, Blackadder. Five minutes later I was in a coach, flying through the London night, bound for the lady's home.

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) Oh, and which lady's home is this? A home for the elderly or home for the mentally disadvantaged?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) No, no, no, no, no, no, no. This was Apsley House. Do you know it?

ATKINSON: (as Edmund Blackadder) Yes, sir. It is the seat of the Duke of Wellington. Those ladies I fancy, would be his nieces.

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Oh, so you fancy them too. Well, I don't blame you.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: (as The Prince Regent) Bravo. Oh, I spent a night of ecstasy with a pair of Wellingtons and I loved it.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: OK. So that's my guest, Hugh Laurie, in an episode of "Blackadder" with Rowan Atkinson. You know, even there you don't sound like yourself exactly, like you're doing a different voice. And there's hardly a character who would be more opposite than House than this kind of like, you know, brainless, vain, shallow character.

LAURIE: Yes. It's true. It's about as far away as you could get, except for this, that it became a common - or maybe it always was a common tactic of House, a strategy that House used, to demonstrate the vacuity of his opponent's argument, was to mimic what he - in his eyes was their stupidity and he would play the fool in order to demonstrate how absurd their arguments are. And sometimes I found myself sort of calling upon that same idiotic set of notes that I played as Prince George, because I've always found it quite comfortable playing stupid people. Now, why would that be? I don't know. But it's felt like a natural thing for me. But it's something House does too, in a sarcastic fashion. He plays stupid sarcastically and does it very well, I think, does it successfully in terms of winning arguments.

GROSS: So I've read that you love motorcycles.

LAURIE: I do. I love them very dearly.

GROSS: And that could be a risky endeavor. You've probably had an accident or two.

LAURIE: I...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: Difficult for me to say, because of course if I own up to haven fallen off, then the insurance company on my next - if I ever have a future employer...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

LAURIE: ...they will start inserting clauses into my contract. But no, Terry, I've never fallen off a motorcycle. I find it in utterly secure and reliable means of transport. Let me put it that way.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: OK. And I've also read that you've had, you know, bouts of depression. And are the two related? Does like a high speed really kind of physical ride do anything to chase away or obscure depression?

LAURIE: I suppose it might. I hadn't thought of that, one as an antidote to the other. I hadn't thought of it, but I suppose that may be true. There's a - the feeling of air rushing over your body at high speed. You can't not think of a sort of cleansing process going on, that things are being swept off you and that may include thoughts, experiences - you know, worries that you may have are being simply almost literally blown off your body, which is - maybe that's a good thing. There could be something to that.

GROSS: So I have to ask you, earlier you were telling me...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: We were talking about pain and House's pain and pain that you experienced. You said that you sometimes - that you used to and still sometimes do induce leg and foot cramps.

LAURIE: Yes.

GROSS: And I'm just sitting here thinking is he pulling my leg about that? Like, did he really do that or is that a joke?

LAURIE: No.

GROSS: So I have to...

LAURIE: I'm really, really not. I could do it for you now.

GROSS: No, no, that's all right.

LAURIE: It just wouldn't make excellent radio, I don't think. Unless I start pounding the desk in agony. Then you might get a sense of it. But, no, I genuinely can do that at a moment's notice and I do. I really do. The strange thing is you can't repeat it. If you induce cramp in your foot or calf you then have to leave it. You can't sort of do it over and over again for some reason.

There must be some physiological reason for that. So I only get sort of four bites at the cherry in a day but I quite often take them. And I just sort of ride it out. And it's a few minutes and it's rather - I know this is making me sound so weird, isn't it?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

GROSS: It is weird. What can I say? It's weird.

LAURIE: It is, isn't it? Yes. Uh, yes. Maybe I should've said that I am actually pulling your leg. I'm not, though, no. This is the truth. This is the truth. I can't explain it. It's just one of them things.

GROSS: So one of the things that you do is play music and piano and some guitar. You sing. So I want to close with "St. James Infirmary" from your recent album of blues and rhythm and blues "Let Them Talk." Just tell us a little bit about what this song means to you and about the kind of piano playing that you like most.

LAURIE: Well, this is, "James Infirmary" is a wonderful old classic song. It's actually much older than the Louie Armstrong version that I, you know, grew up loving. The theory is that it actually comes from and old English folk song and that the St. James Infirmary of the title actually refers to what is now St. James' Palace, oddly enough.

I don't know if that's true or not. It's hard to be sure, but I thought there was something rather appropriate about an old English folk song traveling to America, being reinvented, and then finding some way of bringing it back.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear it. Hugh Laurie, thank you so much for talking with us and good luck with the end of "House" and with the episode that you directed for next week. And do you know what life will be like after "House" for you?

LAURIE: I have no idea. I have absolutely no idea. I still haven't really got used to the - the prospect of not getting up at 4:30, is the first and most delicious thing on my agenda. I'm looking forward to that, but beyond that I have no idea. It's very exciting. Very exciting.

GROSS: Well, good. I wish you the best with that.

LAURIE: Oh, thank you.

GROSS: And thank you again so much.

LAURIE: Thank you, Terry. Thank you very much.

GROSS: Hugh Laurie stars in the Fox TV series "House." He directed next week's episode. The series finale is May 21st. Here's Hugh Laurie at the piano and singing.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "ST. JAMES INFIRMARY")

LAURIE: (Singing) I went down to St. James Infirmary. Saw my baby there. She was stretched out on a long white table. So cold, so sweet, so sweet, so fair. Let her go, let her go. God bless her wherever she may be. She can search this whole wide world over. She won't ever find another man like me.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: A recent DVD release of an imported British drama has all the features of an easily promotable teen movie. It's loaded with sex and violence. It's loaded with tales of epic battles and sinister intrigue. And even the most powerful characters are in danger of being killed at any time. But, says TV critic David Bianculli, this is no new action feature for the younger set - this is a very mature drama for very mature adults.

It's a reissue of a miniseries that was shown on PBS 35 years ago. It's "I, Claudius" starring Derek Jacobi as the most unlikely of Roman emperors.

DAVID BIANCULLI: "I, Claudius" came to American television, imported from the BBC, in 1977 - the same year as another ambitious long-form production, ABC's "Roots," which proved to everyone that miniseries were an exciting and extremely popular new form of television. Of course, "I, Claudius," shown on the PBS series "Masterpiece Theatre," didn't get anything close to the audience that "Roots" did, but it sure got a lot of attention.

And a few years later, when the ABC primetime soap opera "Dynasty" was launched, its creators admitted openly that what they had in mind was a modern-day "I, Claudius." The original "I, Claudius," based on the novel by Robert Graves, covers the reigns of several Roman emperors - Augustus, Tiberius, the famously twisted Caligula and the stuttering, limping Claudius, who narrates the entire tale, reading from his own history.

I am not yet born, he says as the TV drama begins, but I will be, soon. The miniseries boasts impressive performances from several key British actors. Patrick Stewart, long before "Star Trek: The Next Generation," shows up here. So does John Hurt, as a memorably unhinged Caligula. And the women, including Sian Phillips as Livia and Sheila White as Messalina, are deadlier, and even more fascinating, than the males.

Except, that is, for Claudius. Played by Derek Jacobi, it's a performance that spans wide-eyed youth and weary old age. At first, while everyone in Rome is falling victim to the treachery of others, he survives, mostly because he's dismissed as a stuttering idiot.

Well, he stutters, but he's no idiot - and the older he gets, and the more Roman purges he survives, the wiser he is at self-preservation. Once the obviously insane emperor Caligula has declared himself a God, for example, the wrong utterance in conversation with him can lead to instant death. But Claudius, despite his stutter, manages to use his wits quickly enough to survive. Here are John Hurt as Caligula and Derek Jacobi in the role that made him a star as Claudius.

Caligula begins by asking Claudius a seemingly simple question.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV MINISERIES, "I, CLAUDIUS")

JOHN HURT: (as Caligula) How many hours a night do you sleep?

DEREK JACOBI: (as Claudius) Sleep? Uh, uh, eight or n-n-nine, I suppose.

HURT: (as Caligula) Why, I sleep barely three.

JACOBI: (as Claudius) D-do g-gods need more?

HURT: (as Caligula) Do you think I'm mad?

JACOBI: (as Claudius) Mad?

HURT: (as Caligula) Yes. Sometimes I think that I'm going mad. I mean, do you - oh, no, be honest with me. Has that thought ever crossed your mind?

JACOBI: (as Claudius) Never. N-n-never. Why, the idea is p-preposterous. You set the standard of s-sanity for the whole world.

HURT: (as Caligula) Well, then why is there always galloping in my head and why do I sleep so little?

JACOBI: (as Claudius) W-w-well, it's all m-mortal disguise, you-you see. The physical b-body is a great strain. If you're not used to it, which a god isn't. And-and that, uh, explains too, I think, the three hours sleep. You see, undisguised gods never sleep at all.

HURT: (as Caligula) Yes. You're probably right. But then if I'm a god - because I am - then why didn't I think of that?

BIANCULLI: Revisiting "I, Claudius" after so many years is quite a treat. It's a strong reminder of how literate and ambitious the miniseries form used to be - and how much we've lost by its overall disappearance. Except that, like so many other entertainment forms, the miniseries hasn't so much gone extinct as been absorbed.

It's alive and well, in season-long story lines on Showtime's "Homeland" and "Dexter," and on the lengthy narratives of AMC's "Mad Men" and "Breaking Bad." But on television, the extended, complicated narrative began in such productions as "I, Claudius."

The new DVD boxed set from Acorn presents this beautifully, and even includes a bonus feature that, to me, is alone worth the purchase price. It's a full-length documentary from 1967, about an unfinished attempt to film "I, Claudius" way back in 1937.

The documentary is called "The Epic That Never Was," and you may have seen it on public TV several decades ago. I did, and never forgot it. It has all the surviving footage of the aborted "I, Claudius," filmed by Josef von Sternberg and starring Charles Laughton, in the title role. Laughton was amazing and you can tell that from even a brief taste.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOCUMENTARY, "THE EPIC THAT NEVER WAS")

CHARLES LAUGHTON: (as Claudius) I, Claudius, will tell you how to frame your laws. Profiteering and bribery will stop. This senate will function only in the name of Roman justice and all of you who have acquired office dishonestly will be replaced by men who love Rome better than their purses.

BIANCULLI: How wonderful is that? And how wonderful is this 35th anniversary "I, Claudius" set? Not only do you get one fantastic Claudius to enjoy - you get two.

GROSS: David Bianculli is founder and editor of the website TV Worth Watching and teaches TV and film history at Rowan University in New Jersey. He reviewed the 35th anniversary DVD edition of "I, Claudius."

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: You can download podcasts of our show on our website: freshair.npr.org. And you can follow us on Twitter at nprfreshair and on Tumblr at nprfreshair.tumblr.com.I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.