Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on September 30, 2019

Transcript

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.

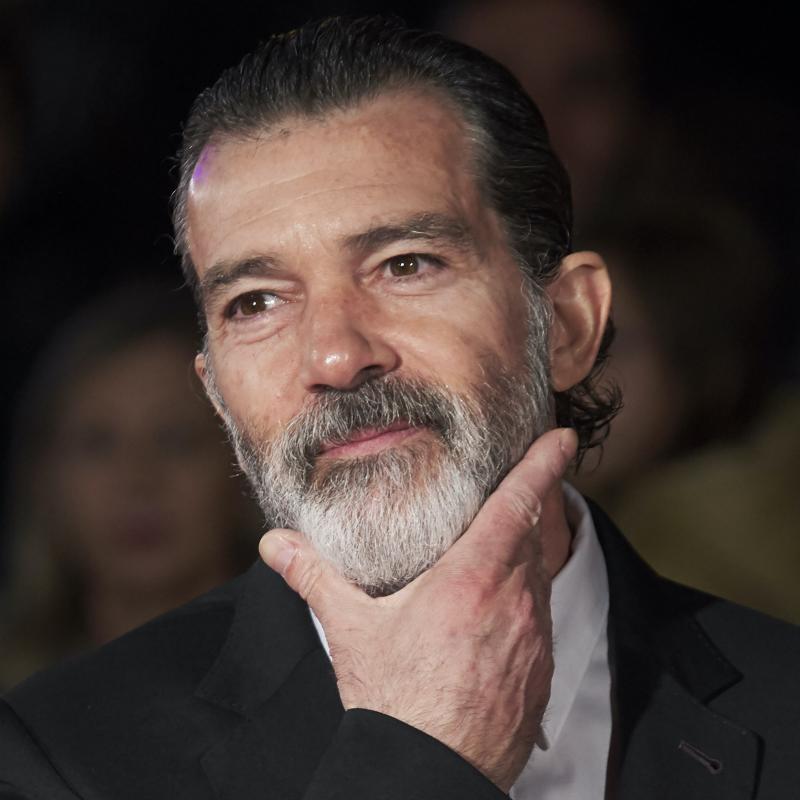

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, editor of the website TV Worth Watching, sitting in for Terry Gross. Today's guest is Antonio Banderas, who was nominated for an Oscar for his starring role in "Pain And Glory," written and directed by his old friend, the Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodovar. "Pain And Glory" also is nominated as best foreign language film. The Oscars are awarded next month, but Banderas has already has won best actor awards at the Cannes Film Festival and from several critics associations.

In "Pain And Glory," Banderas plays a screenwriter and director who lives to make movies but has stopped working because he's suffering from physical pain and pain of the soul. His character, whom filmmaker Almodovar modeled on himself, suffers from insomnia, ulcers, reflux, tendinitis, depression and more. Banderas and Almodovar started making movies together in Spain in the 1980s after the long, repressive regime of General Francisco Franco had ended. Banderas started acting in American films before he could even speak English. In 1992, he costarred in the movie "The Mambo Kings." The following year, he starred opposite Tom Hanks in "Philadelphia." He went on to star in many films, including the "El Mariachi" trilogy, "Spy Kids" and "The Mask Of Zorro." Terry Gross spoke with Antonio Banderas last September.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

TERRY GROSS, BYLINE: Antonio Banderas, welcome to FRESH AIR. You're so good in this new film (laughter), in Almodovar's...

ANTONIO BANDERAS: Thank you.

GROSS: ...New film. It's really a pleasure to have you on our show.

BANDERAS: Thank you. My pleasure to be here.

GROSS: Early in the film, there's a part where you, as - in your role as a director who is afflicted with all kinds of symptoms - is recounting his symptoms. And I know Almodovar suffers from a lot of physical pain. Can we talk about that first? Did he talk to you about why he wrote those lines and the pain that the character he created that you play resonates for him?

BANDERAS: Yes, absolutely. Well, you know, this is a man that actually suffered practically with each one of those physical problems. And so when he's trying just to put part of his life, you know, at front on the screen, tell his story, he needs to just say all of these things, you know, as establishing a physical map of who he is, you know, in terms of pain.

Now, as an actor, when I got in the movie - we actors, we use practically everything that happened in our life in order to create the characters that we create. I suffered a heart attack about 2 1/2 years ago and was an alert in my life. And when I say this, people may just think that I am crazy, but it's one of the best things that ever happened in my life because it just gave me a perspective of who I was. And it just make the important things being on the surface and everything that was not important that I thought was important but it was not important just sunk.

Now, by the time that I start working with Almodovar in this movie, it was very close to this event, this cardiac event that I had. And Pedro said to me, you know, I don't know how to describe it, but since you have the heart attack, there is something different in you. And I don't want you to hide it. I don't want you to just go because if you just show it, it's going to be very close to all of these pains that I describe in the movie. And I want you there in that universe that is absolutely new to me and probably is going to be new, you know, for the spectator, for the public to see you in a completely different context.

GROSS: Did he know...

BANDERAS: So...

GROSS: ...That you had had a heart attack when he asked you to do the role?

BANDERAS: Yes, yes. He knew. He knew from the beginning that I had that, you know, cardiac event.

GROSS: Do you think that's part of the reason why he asked you to do the role, knowing that you...

BANDERAS: I don't know.

GROSS: ...Would really understand what it means to feel vulnerable and to have pain?

BANDERAS: I never asked him that question. But during the period of rehearsals, you know, this is one of the first thing that he said to me. So it was in his mind probably. It was - anyway the eighth movie that I do with Pedro Almodovar. We know each other from 40 years ago. We have done different type of works during all these four decades.

But probably, you know, maybe that event that I had probably played - you know, it was a factor for him to make a decision because he was very, very clear in that aspect. You know, you should just - don't hide that. And in order to do that, I had to left behind - leave behind a number of things because, you know, in reality, I start creating this character in a way nine years ago.

But I didn't know. I didn't know. He called me after 22 years that we didn't work together to play a character in a movie called "The Skin I Live In." And after 22 years that basically I worked in Hollywood, in America, I went there to my first rehearsals with him, you know, all proud of all the work that I have done all of these years, the new things that I have learned as an actor. You know, I have new techniques. I am more secure in front of the camera. I can use my voice in this way and this, blah, blah, blah.

And I put all of those things on the table. And after we were rehearsing for about a week, he said to me, Antonio, you know, all of those things that you have learned in America that may be very useful for the things that you do in America, but they are not useful for me (laughter). And he says something. He made a question that was pretty much like, where are you? And at another point, I kind of, you know, I couldn't understand really him. He says, what - you know, he's just trying to play this kind of power game. You know, he's my friend. So I'm going to defend my position.

And so I went into the shooting defending my position. It was kind of a tense shooting, never dramatic because we are friends. We have been friends for a long time. But, you know, I was, you know, seeing my kind of thing in a very specific way, and he was seeing the kind of thing in another.

Now, what happened is that, at the end of the process, I saw for the first time the movie in the Toronto Film Festival. And, of course, you know, he was director, so he just put in the movie his version, you know, the one that I gave him, you know. And I was so surprised and - that he managed to get out of me a character that I didn't even know I had inside. So at that point, I started, you know, a reflection in my mind that has to do with humility...

(LAUGHTER)

BANDERAS: ...To be humble, to open your ears and to open your eyes to especially those people that, actually, you trust. And I trusted him for many years. He's the first director, really - movie director - that I ever worked with. I admire him. I respect him. I love him. So why I close myself into that kind of thing? So I was just praying that life would give me another opportunity to work with him.

GROSS: Your character is holding everything in. He's holding in his pain. He's holding in a lot of his emotions...

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...While also digging deep into the memories of the past. And because of the pain, he's unable to make films, or at least he thinks he's unable to make films. So you have to communicate a lot just by the way you hold your body and your face and your eyes.

BANDERAS: Correct, yeah.

GROSS: And that's - it's a very - I would imagine that's a very hard thing to do. Within the movie, we eventually learn that your character, the director, has been writing a monologue, and he wants an actor friend of his to perform it. And this actor friend, they had a falling out, like - I don't know - 20 years ago or more. And they had a falling out while this actor was being directed by your character.

And when they come together after your character asks him to perform the monologue, they're talking about, like, how to convey the drama and the pain that is going to be expressed. And I forget whether the director says to the actor or the actor says that another director had told him this, but it was basically, don't overdo it with the sadness. Hold back the tears...

BANDERAS: Correct.

GROSS: ...That's the best way of expressing it. Was that advice Almodovar gave to you or that another director had given to you?

BANDERAS: Yeah. Yeah. He calls that a humid emotion (laughter).

GROSS: Humid?

BANDERAS: Wet emotions.

GROSS: OK, wet.

BANDERAS: Yeah. And he said - he always said to me, you know, I don't want wet emotions. You know, actors, we - you guys love to cry because you think that it's a demonstration that you are real. And - but he said, that's another trick sometimes, too, you know. There are - (laughter). He said to me once that he knew an actress, that she can cry from her right eye or from her left eye.

(LAUGHTER)

BANDERAS: So that's a trick. You can do that, and you can apply all the realities that you want to that, but it's not true. I prefer actors who actually hold back the tears, hold the emotions, you know, that they are more - less busy, more transparent, more economic. That's probably the word, you know, more economic in the emotions.

And he - that's being a constant in Almodovar, which is sometimes a contradiction because people think that Almodovar is a little bit bigger than life, you know, in his expressions and narrative and even colors, for example, in the framing. But then he is very measured with the actors. He likes the actors to be, you know, in a way, more in the way that he direct movies and he has to do with the movies that were done in the '40s and in the '50s.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Antonio Banderas. We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Antonio Banderas. He stars in the new Pedro Almodovar movie "Pain And Glory." He also stars in Steven Soderbergh's film "The Laundromat" based on the story of the Panama Papers, the papers that revealed all the shell companies laundering money in Panama.

You know, whenever I see an Almodovar movie, I always walk away thinking, I wish I lived in the visual world that Almodovar creates for his films because everything, from the way walls are painted in the interiors of houses to the patterns people are wearing in their clothes and the way it's lit, everything is just so, like, visually alive and vibrant, and the colors are all perfect with each other. Whether they're meant to, like, clash or match, they're all just vivid and jumping off the screen and - but seeing this movie, "Pain And Glory," I was thinking, OK, that's the visual life that Almodovar creates on screen, but his interior, he talks about - you know, he writes about how depressed he is and the pain of the soul that he has. And so I - I'm assuming that the interior that he lives in isn't always so brightly decorated.

BANDERAS: No. No, it was a certain point when we met each other at the beginning of the '80s. We were almost like a theater company or like a rock-and-roll group because he loved to work with the same actors. And so we made a number of movies together - "Law Of Desire," "Matador," "Women On The Verge," "Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!" - movies like that, you know. We were all the same people. You know, he used to go out a lot. We all did at that time in the '80s, in the Madrid of the '80s, in what we called The Movement, La Movida, you know, which was a kind of an opposition to the regime of Franco, which just finished at the - 1975, right?

But at some point, I remember I went to America. And I was just calling friends of ours, common friends. And I was saying, how is Almodovar? They said, we don't see him. And I - what do you mean? Said, yeah, no. He's got problems with his back, and he got these migraines. And he got this photophobia. And so he's home, basically. So he doesn't see anybody. So little by little, he started getting totally isolated.

Now, during the process of making this movie, art can be - you know, when you go through a process like this, can be therapeutical (ph) in a way. And I saw Pedro getting out of a hole. And he was saying things that he wanted to say. He was just becoming lighter as the movie was progressing. And by the time that we finished, I have never seen Pedro Almodovar happier than he was at the beginning of this shooting. It was spectacular. We finished the movie a little bit more than one week before we were supposed to, which is unheard of in movies. Believe me.

GROSS: (Laughter) Definitely. Yeah.

BANDERAS: We always finish after. But I think because everything was swell. Everything was going so fluently and so beautiful.

GROSS: So I just want to get back to the fact that you had a heart attack a couple of years before making the movie.

BANDERAS: OK.

GROSS: And you said a nurse in the hospital told you the heart not only pumps blood throughout your body; the heart is a warehouse for feelings and that you should expect to be sad for a few weeks or for a few months following the heart attack and having stents put in. And I'm wondering if that happened, if you were sad and if having been told in advance to expect being sad was helpful to you.

BANDERAS: Yeah. I can tell you about mine because there are thousands of way that you can have a heart attack. In my particular case, you know, yes, that woman that came to me was a nurse at the hospital. And she said that she totally - she was right on. Yeah, I (laughter) became not only very sad but very sensitive to anything. I am not a crier. I was never a crier (laughter). I was, you know, a tough guy, you know? And suddenly I was watching movies, and I was listening to music, and suddenly I got all teary.

And yeah, it's - I don't know. You feel very vulnerable. And you totally understand that there is only one thing that is absolutely perfect, which is death, and that is certain. And everything else is relative, including taxes, as "Laundromat," the other movie with Steven Soderbergh, will demonstrate (laughter).

GROSS: (Laughter) Taxes and laundering money.

BANDERAS: Right (laughter).

GROSS: So when you started working in theater and when you started working with Pedro Almodovar, it was in the decade after Spain's longtime dictator, Francisco Franco, had died. He ruled from 1939 to 1975. The Spanish Civil War was to stop fascist rule, but Spain got fascist rule for a long time. So when Franco died and the restraints and the fear were removed, that's when the counterculture - the artistic counterculture came alive...

BANDERAS: Right.

GROSS: ...In Spain. And you were a part of that, as was Almodovar. Tell us a little bit about what it was like to be making art during that period when, you know, fascism had ended and there was a new generation coming of age without fascism who could express themselves and who could be transgressive in their art if they wanted to be.

BANDERAS: Yeah. Well, when Franco died, I was 15 years old. I was a kid. And I was living in a new Spain that basically, more than repressive - and then my perception at that time as a child, almost, is that we were in kind of an anesthesia. That was the feeling, like, nothing happened. Everything was fine (laughter) in a very kind of eerie way - you know, fine. This guy was there in power. And he was like your uncle. You know, he was always Franco. Yeah, this is what we have.

And so when he died, I start growing into being a man almost in a parallel way that my country was going from a dictatorship to a democracy. And at that time, you start discovering what the dictatorship was. Then you start seeing what freedom is all about. And then you start just looking back and saying, oh, my God, how could I have lived there without knowing that this thing exist? So it was a time for the whole entire Spanish people to discover a new world, to adapt, to prove ourselves that we can be a democratic country, that we can actually decide for our own future.

And there was a group of people - among them Pedro Almodovar and some musicians and fashion designers and photographers and people in the world of art of all kind - that decide to just break with the past and just create something new. So it was a time of a lot of color, a lot of hope and fun and no restrictions in every possible way and about breaking a lot of, you know, morality rules that were monolithic and very conservative in our country. And it was a beautiful time. It was really a beautiful time because we were conscious of that, conscious that we were actually creating a path for the future, something that breaks with the past. And we started establishing another set of rules.

GROSS: What were some of the rules that you most enjoyed breaking in your life or in your art?

BANDERAS: Sexual rules, for example (laughter). I remember 1985, you know, only 10 years after the death of Franco, we did "Law Of Desire." And to that point, you know, not only in the Spanish cinematography field, worldwide cinematography, to just show a relationship between two people from the same sex was almost, you know, anathema. It was forbidden on the screen. But a very interesting reflection I started in that movie to me because my character, who was a homosexual, he killed a guy - early scenes in the movie. And nobody was putting attention to that. That scene was fine. I mean, to kill in a movie is absolutely accepted. Nobody is scandalized about that. In terms of morality, we totally accept that fact. Even in movies for kids, it's fine.

But if you see two people from the same sex just kissing each other on the screen, there was a scandal behind. So there was something wrong about that. (Laughter) And, you know, at the time in 1985, this got in my mind. And I said, no, there is something wrong here in our society. It shouldn't be like this. You know, two people from the same sex can absolutely love each other (laughter). It was very simple.

BIANCULLI: Antonio Banderas speaking to Terry Gross in 2019. He's nominated for a best actor Oscar for his role in "Pain And Glory." After a break, we'll continue their conversation, and critic-at-large John Powers reviews the British series "Giri/Haji" - now available on Netflix.

I’m David Bianculli, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, in for Terry Gross, back with more of Terry's 2019 interview with Antonio Banderas. He's nominated for a best actor Oscar this year for his role in "Pain And Glory," the new film written and directed by Spanish filmmaker Pedro "Pain And Glory" is also nominated in the best foreign language film category. Banderas and Almodovar collaborated frequently earlier in their careers, beginning in the '80s, less than a decade after the death of the fascist dictator Francisco Franco. Franco's rule ended in 1975, ushering in a new era of cultural and artistic freedom in Spain.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: Well, and then you started making movies with Almodovar in the '80s. And there's gay characters and trans characters and straight characters. So coming to Hollywood, where a gay kiss is going to be a huge, big deal (laughter) must have been kind of interesting for you after having opened up the box to all of these possibilities during the countercultural movement after Franco.

BANDERAS: It was very curious because for me, America was the, you know, always the country of freedom. And I was coming from a country that it was not that. And so suddenly I just detected that we took steps into the future (unintelligible) you know, when more ahead of this Hollywood that I found at the beginning of the '90s (laughter). You know, but these things at the end, this is a battle that is going to be won always.

Society and the way that society moves is going to impose, you know, how that is going to be reflected by art. And sometimes, you know, art goes ahead and just propose things before. So it was a matter of time. Now, little by little, you know, you start accepting all of these sexual rules, for example. We were talking about sex - all the, you know, aspects - politics and many other things, you know. But it's very interesting.

But the night that we passed "Pain And Glory" in the Cannes Film Festival, and there, you know, it's 3,000 people in the Palais - basically, the intellectuality of this cinema from all around the world. In the moment that I kiss with another man in the movie - and it's a very strong kiss - there was a gasp (laughter) in the audience that, you know, you detect that it still, you know, is just rare, even in our times - just to see two people from the same sex to kiss on the screen.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Antonio Banderas.

Your father was a police officer. Had he been a police officer under Franco, too?

BANDERAS: Yeah, he was. He was. He was actually chief of police of Malaga, which is the place where I was born.

GROSS: Wow. That's a big position.

BANDERAS: Yeah. Yeah (laughter).

GROSS: So did - that must have - well, what was that like in your family, to have your father be a police officer under a dictator?

BANDERAS: It was good because Franco - police was divided in different, you know, levels. And the level that was really, really political was the Social Brigade. But my father didn't belong to the Social Brigade. He was just a kind of a normal detective, you know, the kind you may find here. He was not under the political boot of the regime. He was just more in frontiers, customs - stuff like that. You know, he used to go to Morocco. It was basically, you know, that customs.

GROSS: Was he afraid that your art and your behavior during the countercultural period in Spain would reflect badly on him and would make him look compromised?

BANDERAS: I don't know because my father, believe it or not - he was a big supporter of me. He helped me, actually. He helped me with funds when I didn't have one penny, and I was living in Madrid, and I didn't have work or anything. And then I started working in the national theater. And somebody said to me - I didn't even know that - you know that you father comes every night, and he sits in the last seat of the orchestra to watch you performing every night? And I said, really? And he says, yeah. Every night he comes here, and he sees you. And then he goes away because he doesn't want you to see him (laughter).

GROSS: Wow. Did you tell him that you knew?

BANDERAS: No, I never did because if he didn't want it, he didn't want it - just to disappoint him.

GROSS: Is he still alive?

BANDERAS: No. My father died in February 2008.

GROSS: So he never knew that you knew.

BANDERAS: Yeah, never knew.

GROSS: So you grew up in Spain. You started your acting career in Spain in theater and in film. Then you decided to move to America, I guess, to make movies here. Problem was you didn't speak any English. And when I think about that, I just can't imagine - it's hard enough to go to any country where you don't speak the language. But to go to that country looking for a job acting in a language that you don't speak, I can't imagine what that must have been like for you. That took a lot of - chutzpah is a word that comes to mind...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: ...To do that.

BANDERAS: Yeah. Well, I - it was kind of an accident, in a way, because we were nominated for an Academy Award at the time for best with "Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown." That's the first time I went to Los Angeles. And then, you know, there was a guy there - we visit a place called ICM - it's an agency for actors - just a visit. You know, they invite us. And there was a person there that was literally taking coffees to the agent. He was not even an agent. And he said to me, do you mind if I represent you here in America? And, as you know, these kind of things that you say, yeah, sure, whatever. I didn't know, I said yeah.

So I went back to Spain after the ceremony and the whole thing. And this guy was actually very perseverant. And at some point, he said to me, listen; you should go to London to have an interview with a man called Arne Glimcher. He wanted to direct this movie called "The Mambo Kings." And it's a movie based on a novel that won the Pulitzer Prize by Oscar Hijuelos. He may have a character for you in that movie. And I say, OK. So he speaks Spanish. And he says, no, he doesn't speak Spanish. He speaks English. I say, so how are we going to do this interview? Said, well, you just manage. And it's like, well, how am I going to manage?

(LAUGHTER)

BANDERAS: So they put me on a plane. And I ended up in London in a restaurant in front of this very elegant man, you know? And I just kind of faked that I was shy, and I speak very little (laughter) And he just talk and talk, and I couldn't understand a word that he said, really. I was just saying yeses and yeah, yeah and of course, of course - things like that.

You know, but I think towards the end of the first dish, he just realized that I couldn't speak a word of English because, I mean, he started just laughing - and this whole - the whole situation became very funny. But for whatever reason, he said to me, OK - very slowly, he explained to me that I should go to New York and do a screen test learning my lines phonetically. And I said to him, yeah, I can do that. I can learn that I - as I learn a song from The Beatles. Yeah, I can do that. So that's how I got into American movies.

I came here to New York. And I did a screen test - several, actually, in a period of time of three or four days. And I learned my lines phonetically. And at the end, they decided, you know, that they were going to take the risk of using me in the movie as an actor. So that was the beginning of my American career.

And I thought it was going to be the exception of the rule, that I was going to go back to Spain and continue doing my movies in Spain, my activities there. But then the movie came out. And Jonathan Demme saw it, and they called me again. And I did screen test with Tom Hanks for "Philadelphia." And I did another movie. And then it was back and forth like this until I met Melanie Griffith. And that changed my life because we fell in love. And the rest is history, you know? And I decided just to move to America.

GROSS: How did you learn how to speak and comprehend English?

BANDERAS: Well, living with people that only spoke that language, you have to actually accelerate the whole entire process - watching television, watching movies, putting attention. And it was very frustrating at the beginning because you may just learn the basic things so you can live, and you can go to the market. You can do the things that are, you know, everyday things. But in - if you're getting a dinner, for example, and people get into a very profound conversation, then you're out.

So you - for two, three, four years, you feel like an idiot. (Laughter) You feel handicap. You cannot actually totally show who you are or what is the way that you think because the complexity of the ideas require of a better, you know, use of the language. And I didn't have it at the time. And even now, you know, I am shy - yeah, still (laughter).

GROSS: I can understand why you feel that way, but I find you very easy to understand, so I want to...

BANDERAS: OK.

GROSS: ...(Laughter) Reassure you on that.

BANDERAS: (Laughter) Right.

GROSS: You've done a lot of action roles...

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...During your career. Is that in part because action films are less dependent on - like, there's usually not, like, long, reflective conversations and voiceovers...

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...In action films.

BANDERAS: Maybe, yeah. I suppose at some point, you know, because I did movies that were very successful, like "Zorro" or "The 13th Warrior" or "Desperado," you know, Hollywood has a way to label you.

GROSS: Yes (laughter).

BANDERAS: You know, that's what you are.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Antonio Banderas. We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JULIAN LAGE'S "SUPERA")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Antonio Banderas. He stars in Pedro Almodovar's new movie "Pain And Glory." He won the best actor award at Cannes Film Festival for his role in this film.

So one of your early action roles in Hollywood - or in America, I should say - was "Desperado." It's part of Robert Rodriguez's Mariachi trilogy. And there's an action scene where you and Salma Hayek are on a roof. And to get away from the bad guys, you have to jump from that roof across a pretty big distance to another roof (laughter).

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: And from what I read, it sounds like there was a construction worker around the corner with a crane. And the director or somebody got the construction worker and the crane to help you with that scene. I really wanted to know what that was like. I want you to describe that experience because it sounds really dangerous to me.

BANDERAS: Yeah. Just - I will just start my explanation saying that I would never do that again.

GROSS: (Laughter).

BANDERAS: (Laughter) It was crazy. We did a movie with practically no money. We did a movie with $3 million. For an action movie, that's practically nothing. There was a guy in the movie, a stunt guy, that I kill, like, nine times. I killed the guy with beard, without a beard, with a mustache, with blond hair, with glasses, without glasses. I mean, I think he's the guy who made more money in the movie, was the stunt guy (laughter).

GROSS: Because there wasn't enough money to hire other people to play each of the parts?

BANDERAS: No. We had only one.

GROSS: So he plays lot of the parts. Yeah.

BANDERAS: All of them (laughter).

GROSS: OK.

BANDERAS: But that scene, yeah. We were hung on a cable that was on a crane. There was not a movie crane or nothing prepared for the movie. And that guy who was - you know, construction worker that was working building a house very close was transporting Salma first and then me from one roof to the other.

GROSS: Like, so you were hanging from a cable...

BANDERAS: That's right.

GROSS: ...As you jumped...

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...From one roof to another.

BANDERAS: That's right. That cable was attached to a harness that we had under our, you know, costume. But it was not very precise because the guy never rehearse it. He never did anything like this. You know, he's not a safety...

GROSS: He's not a movie guy. He's a construction worker.

BANDERAS: No. This is a guy who's just bringing bricks on top of a roof (laughter) but not people. And so I remember the first time I jumped backwards, I - the guy just dropped the cable a little bit too heavy. And I hit with my head the next building. So (laughter)...

GROSS: Oh.

BANDERAS: It was just crazy. So we repeat that many times until the man actually got it. But we were playing with our lives right then. And then there was an explosion behind us, a fire that has to fill the whole entire screen. There was no CGI. That was for real. And I remember the smell of, you know, burned hair (laughter).

GROSS: Oh, no. Your hair?

BANDERAS: Yeah - my hair, Salma's hair and everybody that was behind the camera's hair.

GROSS: Oh.

BANDERAS: (Laughter) Yeah. You know, I...

GROSS: But it's an iconic shot. I mean, like, you throw these, like, grenades down from the roof...

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: And they explode. And they...

BANDERAS: Yeah.

GROSS: They Kill the bad guys, and there's this huge conflagration.

BANDERAS: Correct.

GROSS: And you and Salma Hayek are kind of heroically walking away, facing the camera with a screen full of flame behind you. And it's a very iconic shot. People who've seen the movie will remember it. I think it was on the poster for the movies, too.

BANDERAS: Yeah, it was. Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

BANDERAS: For the video, something like that was on the cover of the video at some point. Yeah. Well, that was very intense (laughter).

GROSS: So you've been in several musicals. You've done the movie adaptation of "Evita," where you played Che. Madonna starred in that movie. You were in "Mambo Kings," where you had to do some singing. That was the film "Mambo Kings." You did "Nine" - a revival of the musical "Nine" on Broadway. And now you're starting a theater in Malaga, the city where you're from in Spain. Why did you do that?

BANDERAS: Because - also because of my heart attack (laughter). After the heart attack, I just - one of the things that came to be very stupid is money. And I just realized that money is nothing but an intellectual, diabolic process in your brain (laughter). And - but a theater is something that you can touch, that you can see, that you can use. You can have people there expressing things.

And so I bought a theater. I don't want to make money with it. It's a nonprofit organization that I put together. It's linked to a school where I have 600 students that they do not only just the academics, their normal studies, but at the same time - in the afternoons, evenings, they do scenic arts. They learn how to dance, how to sing, how to perform and act.

And so we are going to have a second theater there. And I chose "A Chorus Line" because "A Chorus Line" reflect about us - reflect about dreams and the sacrifice to obtain those dreams. And it changed the paradigm of Broadway in 1975. When Broadway reflected, until that time, about itself, the reflection was more, you know, "A Star Has Been Born" (ph), "42nd Street," "Singin' In The Rain." I mean, somebody comes to town and, at the end, is triumphant - you know, comes from nothing to be triumphant.

But "A Chorus Line" changed and just focused on those people that are behind that are not stars, but they are the ones who sustain the industry. And it was beautiful. Since I saw it for the first time, it produced a very interesting effect on me, emotional and also cerebral - you know? - something that I can actually see as being helpful not only just for performers and for people who dedicate their time and their lives to the arts but for anybody, anybody who is looking for excellence.

GROSS: Antonio Banderas, it's been a pleasure to talk with you. Congratulations on "Pain And Glory." Your performance is so good. Thank you for coming on our show.

BANDERAS: Thank you. My pleasure, really.

BIANCULLI: Antonio Banderas speaking to Terry Gross in 2019. He's nominated for a best actor Oscar for his role in "Pain and Glory." The Oscars will be awarded next month. After a break, our critic-at-large John Powers reviews "Giri/Haji," a British TV series now available for streaming on Netflix. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF BOB MARLEY AND THE WAILERS' "MEMPHIS")

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. The new British TV series "Giri/Haji," which is streaming on Netflix, centers on a Tokyo policeman who goes to London to bring home a murderer. While this may sound like a familiar storyline, our critic-at-large John Powers says the show is an offbeat original that kept him hooked from beginning to end.

JOHN POWERS, BYLINE: Back in the salad days of cable TV, Bruce Springsteen wrote an uncharacteristically flippant song called "57 Channels (And Nothin' On)." Three decades later, we're all singing a different tune. There's so much on TV that it's overwhelming. I sigh each time a friend tells me that I just got to watch some show that I've never even heard of. Feel free to start sighing because I'm about to do that to you. You've just got to watch "Giri/Haji," an entertaining BBC series that's been available on Netflix for a few weeks now but hasn't gotten nearly the attention it deserves.

Created and written by Joe Barton, "Giri/Haji" is a story of cultural cross-pollination. The show is in both English and subtitled Japanese that also cross-pollinates genres - mixing cop show, yakuza thriller, love story, anime and hokey family melodrama, all spiked with bits of offbeat comedy. "Giri/Haji" is unlike anything else on TV.

Takehiro Hira starts as Kenzo Mori, a Tokyo police detective who gets sent to London to bring back his brother Yuto, a Yakuza gang member played by ultra-handsome Yosuke Kubozuka from the Martin Scorsese film "Silence." Yuto murdered a rival yakuza boss' nephew in London, and if he's not returned to Japan, there will be a gang war. To hide his real mission in London, Kenzo pretends to take a criminology course taught by Sarah Weitzmann - that's Scottish actress Kelly Macdonald - a neurotically garrulous London cop. To penetrate the London underworld, Kenzo enlists the aid of Rodney Yamaguchi, a drug-addicted, half-Japanese rent boy, played with fast-talking panache by Will Sharpe. Kenzo's soon dealing with a slew of other characters, from an Afro-British female assassin to a wannabe yakuza thug who seems to have parachuted in from a Guy Ritchie movie.

Meanwhile, Kenzo's rebellious teenage daughter, Taki, has run away from home and flown to join her dad in London. As if that weren't enough, the show's teeming with other characters back in Tokyo. There's Kenzo's super-competent wife Rei, his withholding mom and dying father, his trustworthy partner, his slippery boss, a gangster's beautiful daughter, plus assorted yakuza who are preparing for war. They're all waiting for Kenzo to catch up with Yuto before he's arrested by the British cops, who have a CCTV photo of him at the murder scene.

Here, Sarah finds Kenzo napping in the corridor outside Rodney's flat and suggests that he knows more about the murder than he's letting on.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "GIRI/HAJI")

KELLY MACDONALD: (As Sarah Weitzmann) So here's what I think. I think you know the man in the mug shot. I think you're looking for him. And I think he killed Saburo.

TAKEHIRO HIRA: (As Kenzo Mori) His name is Yuto. He's my brother.

MACDONALD: (As Sarah Weitzmann) You're close with your brother?

HIRA: (As Kenzo Mori) We were long ago, when we were not fighting. What are you going to do, Mrs. Weitzmann?

MACDONALD: (As Sarah Weitzmann) Sarah.

HIRA: (As Kenzo Mori) Sarah, what are you going to do about Yuto?

MACDONALD: (As Sarah Weitzmann) If we find Yuto, he'll be arrested. And if you try to obstruct that, you'll be arrested too.

HIRA: (As Kenzo Mori) And the fact that you know I'm his brother now?

MACDONALD: (As Sarah Weitzmann) I don't know.

POWERS: Often, when a TV show has scads of plot, what gets lost is our feeling for the characters, who feel like mere ciphers - not so here. Weirdly enough, given the show's weirdness, you find yourself caring about even secondary figures, actively hoping, for instance, that Kenzo's loyal partner won't get killed by the yakuza back in Tokyo. And you worry for Rodney, who, in Sharpe's terrific performance, goes from being an amusingly shallow street cynic to a young man floored by emotional pain.

In English, the words Giri and Haji mean duty and shame, respectively. These concepts are the poles between which all the show's characters move and which often seem to ensnare them, as Rei is trapped by her wifely dutifulness to Kenzo, who ignores her, or Yuto must deal with the shame he's brought on both his own family and his crime family. The characters most caught in this duty-shame thicket turn out to be our heroes. Kenzo seems crushed by the weight of constantly trying to fulfill his duty as a cop, a husband, a father and a brother when many of his deepest desires pull him in directions that he knows he should find shameful. As for the likable Sarah, she discovers that her sense of herself as a good, duty-obeying person may not be as true as she'd like to think.

Now, nobody would ever accuse "Giri/Haji" of Marie Kondo minimalism, and, in truth, its excesses can get a bit silly. But I didn't care, and I suspect you won't either. For as it leapfrogs in time and cuts between London and Tokyo, this is a show positively bursting with compelling scenes. Surprise deaths and illicit trysts, lopped-off fingers and snakes in mailboxes, yakuza gun battles, heartfelt confessions and a stunning rooftop finale that you will not be expecting - I guarantee it. Why, there's even a Yom Kippur dinner. Unabashedly overstuffed, "Giri/Haji" is one show that couldn't care less about the life-changing magic of tidying up.

BIANCULLI: Critic-at-large John Powers reviewed "Giri/Haji," now streaming on Netflix.

On Monday's show, our guests will be filmmakers Julia Reichert and Steve Bognar. Their Oscar-nominated documentary "American Factory" follows what happens when a Chinese glass manufacturer reopens a shuttered GM plant in Ohio. It's the first film distributed by the Obamas' new production company, Higher Ground. I hope you can join us.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE DOGGY CATS' "HAPPY DOG")

BIANCULLI: FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham, with additional engineering support from Joyce Lieberman and Julian Herzfeld. Our associate producer for digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. For Terry Gross, I'm David Bianculli.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE DOGGY CATS' "HAPPY DOG")