Horror Legend George Romero

Romero made his first film, "Night of the Living Dead," on a shoestring budget on the weekends. The film, about a cadre of flesh eating zombies, became a cult classic and a copy is now in the archives of the New York Museum of Modern Art. Romero's subsequent successes included "Dawn of the Dead," "Day of the Dead," "Martin""Creepshow," and "Monkey Shines." Four of his movies have just been reissued on video. Originally aired 7/18/88.

Other segments from the episode on July 17, 1998

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: JULY 17, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 071701np.217

Type: FEATURE

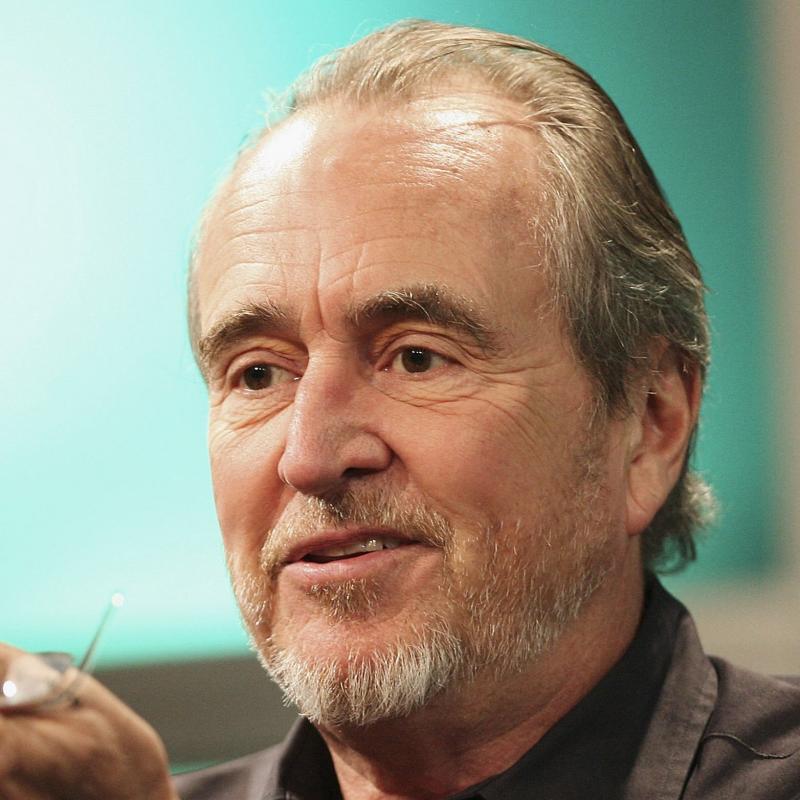

Head: Wes Craven

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "SCREAM")

SOUNDBITE OF TELEPHONE RINGING

ACTRESS: Tatum, just get in the car.

ACTOR: Hello, Sidney.

ACTRESS: Hi. Who is this?

ACTOR: You tell me.

ACTRESS: Well, I -- I have no idea.

ACTOR: Scary night, isn't it? With the murders and all, it's like right out of a horror movie or something.

ACTRESS: Randy, you gave yourself away. Are you calling from work, 'cause Tatum's on her way over.

ACTOR: Do you like scary movies, Sidney?

ACTRESS: I like that thing you're doing with your voice, Randy. It's sexy.

ACTOR: What's your favorite scary movie?

ACTRESS: Oh, come on. You know I don't watch such (EXPLETIVE DELETED).

ACTOR: Why not? Too scared?

ACTRESS: No, no, it's just what's the point? They're all the same -- some stupid killer stalking some big-breasted girl who can't act, who's always running up the stairs when she should be going out the front door. It's insulting.

ACTOR: Are you alone in the house?

ACTRESS: Randy, that's so unoriginal. I'm disappointed in you.

ACTOR: Maybe that's because I'm not Randy.

ACTRESS: So, who are you?

ACTOR: The question isn't "who am I?" The question is: "Where am I?"

ACTRESS: So where are you?

ACTOR: Your front porch.

GROSS: Well, that's how the "Scream" phenomenon started. Scream and its popular sequel "Scream 2," which just came out on video, are horror films that also satirize the cliches of the genre. It's a winning combination, judging from the film's box office success.

The director of both films, Wes Craven, has created, subverted and lampooned the rules of the horror genre. He's made his name directing horror films, such as "Nightmare on Elm Street," "Vampire in Brooklyn," "The Hills Have Eyes," and "Last House on the Left."

Last winter, when Scream 2 was in theaters, we called Wes Craven and asked him why he thinks the hybrid of horror and satire works so well.

WES CRAVEN, DIRECTOR, "SCREAM 2": I think the fact was that horror had reached one of its sort of classical, cyclical stages of ennui on the part of the audience. You know, it just had gone so far along the same lines that people were bored with it and kind of knew what to expect.

And it kind of was in that place where it needed to be satirized, at least before you went on and did something new. You had to sort of acknowledge "this is where we've been and I know you're all bored and I know you're thinking you know what's going to happen."

So that became kind of the charm of it. In that sense, it's kind of a release, you know. It's like a joke about anything, and there's kind of a rush of relief that it's being talked about very frankly, you know. So in the sense that you say "we know horror films have been either boring or stupid or predictable" -- that there's kind of a rush of relief because they know at least they're in the presence of somebody who is smart enough to figure that much out. Now, let's see if they can do something new.

GROSS: Tell me what -- what you found most predictable. Your characters have some opinions on that. What -- what's your opinions?

CRAVEN: Well, you know, you could quote some of the characters, you know, the big-breasted girl who runs upstairs instead of out the front door when there's a threat. And you know, who always goes to investigate and you know sort of does the stupid thing, rather than the smart thing; the classic situation of the girl running away from the monastery and always falling down. You know, there's all those cliches in horror films that, you know, we wanted to avoid and also acknowledge -- or stand on their head.

So I think it was -- it was a large part of that; just the sort of stupidity; a sort of a built-in sexism quite often; a sense of gore for gore's sake. And also, a very heavy emphasis on the sort of killer at the expense of any characterization of, you know, of the more normal people, if you will.

And also a complete lack of recognition of the fact that these were events that were happening within the context of a society that had movies about these subjects. You know, people in the movies of this sort had never commented on the fact that they were in a situation very similar to movies that we all know and could easily talk about.

GROSS: Right. And that they could use that knowledge to help them.

LAUGHTER

CRAVEN: Exactly.

GROSS: In the press kit for Scream 2, one of the producers is quoted as saying that she is awed by your ability to evoke terror from the actors you work with. She says: "He can make an actor so terrified that you actually believe these things were happening to that person." What is she referring to?

LAUGHTER

CRAVEN: Well, I -- you know, I don't know exactly. You'd have to ask her. I mean, you know, part of the job is to -- to get that sense of the reality of situations when actors and actresses are surrounded by crew and cameras and not much is really happening, you know, in the actual, physical space they're in.

You know, try to remind them of things that they might have filmed three weeks before in a, you know, totally different environment that will cut immediately either to or from the moment they're in now. So you -- you kind of -- you know, you're kind of their ally in putting them into context of that sort of ephemeral thing which is the movie that's going to be, but is not right at the moment.

You know, it -- that -- that's to me one of the biggest tricks of directing is just trying to -- trying to make them see the movie that isn't done yet or isn't, you know, is hardly begun.

GROSS: 'Cause they're just seeing the moment that they're shooting right now and you want them to see what happened just before and what's about to happen.

CRAVEN: Right. And what's happened to the character and -- and, you know, what it means personally and -- and, you know, what might have frightened her 10 minutes before in the movie that the actress might have completely forgotten about. I mean -- and it's sometimes just -- you know, in conversations with the actor or actress.

For instance -- what's the specific example? I'd be working with Drew Barrymore. When she first came on the location, she and I stayed up late one night and just talked about our lives. And from that I learned a lot of personal things.

Her extreme connection to animal threats that I was able to use. So quite often, it was -- when she was reacting to things that are in the script where -- let's say, somebody breaking a window and trying to get at her, it was -- she and I were talking about what was happening to a puppy in a news article about somebody who had tortured a dog.

You know, so's there's all sorts of tricks. You're just trying to find these sort of, you know, the commensurate place in their -- in their subconscious, in their real life, and connect it to the imaginary events in a way that's meaningful to them. And it's different for every single actor and actress.

GROSS: Hmm. Wes Craven is my guest.

You know, in the opening of Scream 2, Jada Pinkett (ph) and Omar Aves (ph) play -- play two people who are going to the movies. They're on a date and they're going to see a horror film called "Stab." And Stab is the film version of the murders that had taken place in their town. And actually, these were the murders depicted in Scream 1.

CRAVEN: Uh-huh.

GROSS: And Jada Pinkett is at this horror film very reluctantly. I mean, she doesn't like horror films. She thinks they're kind of racist, too, because if there's an African-American in it, they're going to get killed off right away. But you know, she -- she doesn't -- she doesn't like these horror films.

And everything that's happening in the theater is really her worst nightmare. There's -- the teenagers are dressed in the masks that the killer wears in the movie. They've obviously seen the movie like dozens of times and they're back again. And they're -- they're kind of chanting in race -- and, you know, there's a lot of bloodlust in the theater.

CRAVEN: Uh-huh.

GROSS: And I'm wondering if you've ever seen strange reactions to your films -- reactions that you might have not been very comfortable with; where -- where the audience is getting more into the bloodlust than in identifying with -- more into identifying with the killer than the victim.

CRAVEN: Right. I'd be a liar if I said I had not been in that situation, because I have. And when I have, it's been very disturbing. And certainly that scene was designed to reflect that, you know.

To the extent that I -- it sort of says to the audience: to the extent that you're enjoying somebody suffering and dying on Scream, you are out of touch with reality. And obviously, that whole scene is, you know, designed to juxtapose a screen death with a natural death within the theater, and the shock of the audience when they finally realize that what they thought was a big publicity joke was an actual murder.

So, there is a condemnation of that reaction to that kind of film at that moment, and I think it's quite shocking. And it was a -- you know, it was a wake-up call in a way. The entire film has that theme running throughout it -- the theme of: Do these films encourage, cause, or, you know, such behavior? Or do they, if nothing else, sort of trivialize suffering?

GROSS: I know when I was growing up in the '50s and '60s, "horror film" meant usually a supernatural film -- you know, "Frankenstein," "Dracula," "Wolfman." You're one of the people who made the horror film more about teen anxieties and you know, slashers who prey on teenagers. Sometimes those slashers are fellow teenagers; sometimes they're more supernatural kind of figures, like Freddie Kruger.

So tell me a little bit about how you think the meaning of horror films became transformed.

CRAVEN: Well, it's -- I think they're quite profound films. You know, they -- are dealing with fear, which is certainly one of the primal, emotions, and one of the most immediate signals of danger and the necessity for taking action or else not surviving. You know, so you can't get much more basic than that.

And they always sort of perceive, you know, where sort of that sub-cutaneous subconscious fear that's in the culture at the time. You know, there were lots of films in the '50s about, you know, the effects of atomic energy.

GROSS: Mmm-hm.

CRAVEN: There were early-on films, I think, even at he dawning of science about, you know, the effects of science on human conduct, for instance, like Frankenstein, you know, where you have -- it's all based on what can be done medically, you know, to this person, and how that is either in control or not in control.

Then there was a long period of sort of psychosis as, you know, sort of the key element of fear because it seemed like there were so many things that had happened in society. I think even post-World War II, where you had culture coming out of the sort of, you know, coming out of shock of what they had just seen, of an entire world at war and these sort of horrendous events being perpetrated by, you know, by the Nazis, and in a sense by everybody that, you know, went to war against each other.

GROSS: "Psycho" would be a good example of that.

CRAVEN: Psycho was a great example of that, and I wanted to mention that, you know, because that is a pure case of not a monster in the sense of a, you know, "Godzilla" or something, but it's -- it's a human monster. I think, you know, horror films like Godzilla and "King Kong" are kind of a relief in a way because they are so removed from our reality. They're a little bit more of a popular entertainment, although I think in some ways that they speak often to a sort of a subconscious tread that we use -- botched nature so much or offended it so much that it's going to come back and get us.

GROSS: My guest is Wes Craven. He directed Scream, Scream 2 and A Nightmare on Elm Street. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Back with horror film director Wes Craven. His films include Scream and Scream 2.

Now, I know you didn't see many movies as a kid. I think your parents were very religious?

CRAVEN: Right.

GROSS: And what were their fears about movies?

CRAVEN: Well, I think that -- as much as I can put it together, because it was never expressed so much as it just was a fait accompli, when you know, we just didn't go to movies -- was that they were just too worldly, using that term that is used in that fundamentalist world. And that basically, I think, meant they were too sexual and too -- I think probably the sexuality of it more than anything else was what disturbed them.

But you know, the fact of the themes and the subjects were too -- too risque, too sexual, too whatever for -- to be of any good to the mind and body, which was considered the tabernacle of the Holy Spirit. So you know, there was -- it was kind of a panoply of things that were not done or allowed, you know -- smoking, drinking, playing cards, dancing. All of those things were -- were forbidden; that simply were not part of my life.

And it wasn't a huge problem for me. I mean, I -- you know, if you're not aware of something, it's simply not there in a way. And I was...

GROSS: Well, where -- where did you grow up? I mean, and how -- how...

CRAVEN: Cleveland, Ohio. It's -- you know, it wasn't like I was living out in the middle of, you know, Holy Roller territory. It was just a fundamentalist Baptist Church and my mother was very, very involved in the church, and the church was virtually the core of our social lives. You know, we went all day Sundays and then Wednesdays for prayer meetings, and church camps and church daily vacation bible schools and everything else. It was -- it was my world until I broke out of it. So ...

GROSS: Do you feel that any of your horror films have addressed your innermost fears?

CRAVEN: Oh, I think they all have. You know, I think there's a great deal in there that -- that has to do with that. And you know, I know that Freddie Kruger -- and this is not to be -- you know, this is the sort of thing that, you know, one's mother in Cleveland can hear by third-hand and be horrified by -- but I think there was -- there's a certain -- a fear that I had for my father, for instance, that comes out in, you know, in a grotesque form in, like, a Freddie Kruger, who is like the ultimate patriarchal nefarious character, you know -- who is dangerous and takes delight in sort of scaring the younger.

That -- not that my father chased me around with a glove full of knives, but it was just like to me he was a scary person. I -- he was not around a great deal and he had a sharp anger, you know, a bad temper. And I remember being quite -- quite afraid of him. I'm sure I translated some of that -- those feelings as a small child into those kinds of characters.

And a lot of my films have to do with sons facing -- for instance, in "Shocker," you know, facing a father who was a killer, and who says basically you're gonna be the same thing.

So you know, I don't think they would be anywhere nearly as -- as strong as they have been if they were not in some way reflecting issues that were, you know, from deep inside myself.

GROSS: Speaking of Freddie Kruger, do you remember how you came up with that image of a glove full of knives?

CRAVEN: It was -- it was a pretty methodical sort of intellectual process. I mean, I was trying to work off of primal and ancient sort of atavistic images and themes, you know, since I figured I was dealing basically with dreams which were some sort of primal theater; you know, some sort of brain theater, if you will -- brain cinema.

I was trying to go back to the very beginnings of everything. So it -- you know, it was the father figure and it was -- the weapon was, you know, what I thought was the epitome of human ability was the hand, you know, the human hand, which is so -- so remarkable and so far advanced from any other animal.

And going back beyond that, the primal threat that I, you know, surmised -- must have faced primitive man was, first of all, edged and pointed weapons of tooth and fang and claw and talon -- and just put that onto the -- attached that to the -- to that extraordinary instrument of good and evil of the human hand.

GROSS: Your last couple of horror films, Scream and Scream 2, have been so successful. Do you want to use that success to keep making more horror films? Or, would you like to get away from the genre and -- and do only other things now, or mix it up?

CRAVEN: Very much like to mix it up. I mean, I feel like, you know, I've had really an interesting career in that genre, partially from choice, partially from the fact that it was very difficult to get work outside. With the two Screams, I've had a tremendous amount of feedback now from studios and from producers saying, you know, we can see you can do just about anything, because there is comedy in there and there is -- there is real relationships and really great performances.

So we're developing other projects that are, you know, out of the genre. I would like to do "Scream 3" because first of all it was a great challenge doing a sequel that has done as well as the first one -- that rarely, rarely is done.

GROSS: Yes, even your characters know how hard it is to make a good sequel.

CRAVEN: Yeah, it really is. And then, you know, it's now virtually at the same mark that the first one was at. And I can't think of anybody that's done three in a row really, really well. So that's a great challenge.

After that, I wouldn't mind saying good-bye forever to horror. If I could, I think that would be my choice, and just to go on into other -- other sorts of films.

GROSS: Thank you so much for talking with us. I should let you get back to work.

CRAVEN: OK, Terry.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, SCENE FROM "SCREAM 2")

ACTOR: OK, let's get down to business. The way I see it, someone's out to make a sequel. You know, cash in on all the movie murder hoopla. So it's our job to observe the rules of the sequel.

Number one: the body count is always bigger. Number two: Death scenes always much more elaborate -- more blood, more gore, carnage candy. Your core audience just expects it. And number three: If you want your sequel to become a franchise, never ever ...

ACTOR: How do we find the killer, Randy? That's what I want to know.

ACTOR: Hmmm. Let's look at the suspects. There's Derek, the obvious boyfriend. Hello, Billy Loomis (ph) -- the guy's premed and his (unintelligible) service won't conveniently miss every major vein and artery.

ACTOR: So you think it's Derek.

ACTOR: Not so fast. Let's assume the killer or (s) has half a brain. He's not a Nick at Night rerun type of guy. He wants to break some new ground. Right?

ACTOR: Right.

ACTOR: So forget the boyfriend. It's tired. Who else do we got?

ACTOR: There's ...

ACTOR: Mickey, the freaky Tarantino film student.

ACTOR: But if he's a suspect, so am I. So let's move on.

ACTOR: Well, let's not move on. Maybe you are a suspect.

ACTOR: Well, if I'm a suspect, you're a suspect.

ACTOR: You have a point. OK. Let's move on.

GROSS: A scene from Scream 2, which has just come out on video. Our interview with Wes Craven was recorded last winter. He's now working on "Hollyweird," a new TV show premiering this fall on Fox and he's directing the film "Fifty Violins" starring Madonna.

Coming up, a review of the new film "There's Something About Mary."

This is FRESH AIR.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Wes Craven

High: Wes Craven, one of the foremost directors of horror films. His credits include "Last House on the Left," "The Hills Have Eyes," and "Nightmare on Elm Street." His latest film is "Scream 2" the sequel to his 1996 film "Scream." Both are horror films that poke fun at the genre.

Spec: Movie Industry; Horror Films; Wes Craven; Culture; Post-Modernism

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Wes Craven

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: JULY 17, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 071702NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: There's Something About Mary

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:55

TERRY GROSS, HOST: "There's Something About Mary" is a new comedy by the guys who made "Dumb and Dumber."

Our film critic John Powers says it's smarter than you think.

JOHN POWERS, FRESH AIR COMMENTATOR: We live in age of gleeful bad taste, from the racial jibes of Howard Stern to the barrage of toilet jokes on the overrated TV show South Park. If anyone would seem genetically engineered to thrive in this era, it's the Farrelly Brothers, Peter and Bobby, who made their name with the international hit Dumb and Dumber.

The Farrellys have a genuine gift for gross, rollicking comedy, and in their new movie, There's Something About Mary, they've concocted outrages so memorable, they're certain to become cultural touchstones. The movie begins with a prologue set in 1985 Rhode Island.

Ben Stiller plays Ted, a high school geek with braces and Rod Stewart hair, who lucks into a prom date with the most desirable girl in school. Her name is, you guessed it, Mary, and she's played by Cameron Diaz.

But on prom night, Ted accidentally gets his privates caught on his pants zipper, and in the ensuing chaos, which involves more and more people, he appears to lose Mary forever.

Fourteen years later though, Ted's still thinking of Mary, so he hires a sleazy private detective named Pat Healey (ph), played by Matt Dillon. Healey finds Mary in Miami, but he falls for her too. Soon, he and Ted and a couple of others are all vying for this gorgeous blonde dream girl, who's inclined to say things like: "let's go upstairs and watch SportsCenter."

Of course, to talk about a Farrelly movie in terms of its story line is to miss the point. For what There's Something About Mary is really about is bombarding us with jokes, many that taste the limits of good taste -- gags about masturbation, slapstick with mistreated animals, schtick about crippled men writhing on their metal canes, and greasy mayhem with retarded people, included Mary's brother Warren (ph).

Yet the Farrellys have developed since Dumb and Dumber and Kingpin, and what keeps their movie from being truly offensive is that its outrages are never mean-spirited.

In fact, the whole thing's sweet-natured, as in the scene when Ted and Mary, having just remet, go out and corn dogs.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "THERE'S SOMETHING ABOUT MARY")

CAMERON DIAZ, ACTRESS, AS MARY: Do you want another one?

BEN STILLER, ACTOR, AS TED: Sure, yeah. Hey Dockie, couple more nitrate-sicles, please.

ACTOR: Two corn dogs, coming up.

DIAZ: You know, I don't think that they have enough meats on stick. No, seriously...

STILLER: Really.

DIAZ: I mean, if you think about it, they have plenty of sweets, right?

STILLER: Yes.

DIAZ: They have lollipops, they have fudgesicles, they have popscicles, but they don't have any other meat on stick.

STILLER: Meats. Yes. You don't see that many meats on sticks. And that's...

DIAZ: No, absolutely not.

STILLER: Do you know what -- do you know what I'd like to see? I'd like to see more meats in a cone. You don't hardly ever see that. You know, just that...

DIAZ: That's clever.

STILLER: ... that's an idea that I think is waiting to pop.

LAUGHTER

Just like a nice, you know, nice big oversized waffle cone stuffed full of chopped liver...

DIAZ: Chopped liver.

DIAZ AND STILLER: Exactly.

LAUGHTER

DIAZ: It's too bad you don't live here, Ted.

STILLER: Yeah?

DIAZ: Yeah. We have a lot in common.

POWERS: The movie's most hilarious bits can't be played on the radio, either because they're too visual, like the uproarious scenes involving a dog that's first sedated, then plied with speed, or because they're so obscene, like the zipper scene, or a latter gag involving a strange sort of hair gel.

These set pieces had me laughing out loud, and made it easy to ignore that many of the Farrellys' jokes don't come off, and their shooting style, while more polished than in Dumb and Dumber, is still painfully slobby. At times, the movie is barely in focus.

But as "The Wedding Singer" showed, a comedy doesn't have to be well-made to be a hit, especially when it features likable performers. Diaz brings buoyant innocence to the title role, and frankly that's necessary, since the character of Mary has none of the comic pizzazz of the characters played by Carol Lombard, Katherine Hepburn, or Barbara Stanwick (ph).

Real guys' guys, the Farrellys have yet to write a single female role that's as distinctive or as funny as all their men. That's why the movie's real linchpin is not Mary but Ted. Stiller's not a great actor, but he gives Ted a hapless charm, and wins our affection with his greatest gift as a performer, a slow double take at the unbelievable things that are happening all around him.

There's Something About Mary has enough gross out humor that you'll almost certainly be reading earnest op-ed pieces about the "new obscenity," or the moral decline in American culture. I can already hear Bill Bennett's hard drive whirring.

But while the movie is pointedly crude, it's a dumb comedy made by smart people. There's nothing especially decadent about it. A movie whose aim is to make you laugh, it belongs to the same great tradition of anarchic popular comedy as the Keystone Kops, the Three Stooges, the Marx Brothers, Jerry Lewis, and the National Lampoon movies, which is to say, it's as American as apple pie. An apple pie in the face.

GROSS: John Powers is film critic for Vogue.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: John Powers; Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Film critic John Powers reviews "There's Something About Mary." The new movie from Peter & Bobby Farrelly who made the films "Dumb and Dumber," and Kingpin.

Spec: Movie Industry; There's Something About Mary

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: There's Something About Mary

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.