Ebert & Coppola, Live from Cannes

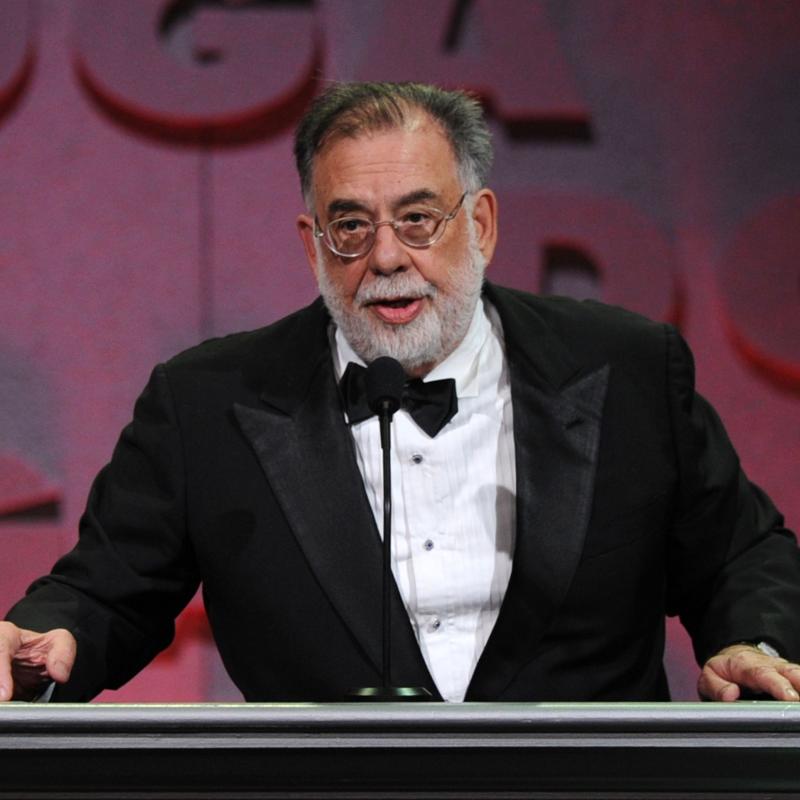

An interview with film director Francis Ford Coppola, recorded at this year's Cannes Film Festival.

Film critic Roger Ebert talks with Coppola about the re-edited version of his 1979 epic Apocalypse Now. The new cut includes an additional 49 minutes of material. It is currently showing in New York and L.A., and opens in other cities over the next couple of weeks.

Other segments from the episode on August 6, 2001

Transcript

DATE August 6, 2001 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Filler: By policy of WHYY, this information is restricted and has

been omitted from this transcript

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Francis Ford Coppola discusses his career

NEAL CONAN, host:

Today, we're talking about Francis Ford Coppola and his movie "Apocalypse Now

Redux." Terry Gross spoke with the filmmaker in 1997.

TERRY GROSS, host:

I'm interested in some things about your family. I think it was your maternal

grandfather who actually owned several movie theaters. What years did he own

them? Were you alive?

Mr. FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: No. This would be really in the '20s, I would

guess, and in fact, they not only owned some theaters--and theaters that

catered pretty much to Italian-American audiences, but they lived on top of

it. And so all the family would have different jobs. My grandmother would

take the tickets and the younger, mischievous brother, Victor--you know,

people in those days used to put their babies in the lobby and so that--he

would walk through and say, `Baby crying. Baby crying.' And you know, they

would really run these little theaters.

And then from that, he actually began to go to Italy and acquire some films

for Italian-American distribution and his company--also he did music rolls,

'cause primarily, he was a songwriter and a composer and a wonderful one I

think. And his music roll company was called Paramount Music Rolls and some

of his friends in that time, in the '20s, were becoming involved in a movie

studio and as the story goes, they were talking to him and looking for a name

and he suggested, `We'll call it Paramount,' `(Italian spoken).' And that was

Balaban and Katz, who later were the partners in what later became Paramount.

GROSS: That's quite a brush with early movie history.

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, I have on the other side, another interesting story. My

other grandfather--Carmine Coppola's grandfather, Augustino, was a very fine,

you know, engineer and tool and die maker, made mechanical things. And he was

called upon to engineer and build a new device that turned out to be the

Vitaphone, which was the first sound talkie movie that when they made "The

Jazz Singer" with Al Jolson it was ...(unintelligible) in our museum. There's

a beautiful museum in the winery and there's a picture of him with the

Vitaphone that he's just built.

GROSS: Can you sing a verse of a song that your grandfather wrote?

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, sure, I will sing for you. In "The Godfather" there was

a whole sequence in a little Italian-American music hall where they sang a

song that was called "Senza Mamma" and it went sort of like, (singing in

Italian). It's all about crying because he ran off with sort of a woman of no

account and then his mother died.

GROSS: So that was your grandfather's song?

Mr. COPPOLA: Yeah.

GROSS: Oh, that's great.

Mr. COPPOLA: That's a Neapolitan song.

GROSS: Huh. So I think it was your grandfather who gave you--What?--a

16-millimeter projector when you were a boy?

Mr. COPPOLA: That's right. In '49, I had polio and I was paralyzed for a

year and he did bring me, you know, a kind of 16-millimeter projector. It was

a young people's projector. It wasn't a, you know, serious--I mean, it was a

real working 16-millimeter projector, but it was of, you know, toy quality.

But I certainly loved that.

GROSS: So what did you project in it?

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, unfortunately, 'cause it was 16-millimeter, there were

only the couple of little film clips that I had. Most of what film I could

play with was in 8-millimeter and there I had a number of cartoons and some

home movies. And also, my father had one of the very early tape recorders,

the Ekor(ph) home tape recorder, and I had it by my bed when I was in that

period of being paralyzed. And I used to try to make soundtracks and

synchronize them to make them play in sync with the movies.

GROSS: And what would be on the soundtracks?

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, it would be stuff like, `Well, here we go. Yeah.

Da-da-da-da-da-da-da. Hi, Mickey. No, no, no, watch out. The fire.' Things

like that.

GROSS: So how paralyzed were you?

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, I couldn't walk and I couldn't move my left arm.

GROSS: So you spent a year basically away from the rest of the world?

Mr. COPPOLA: I was in a bedroom on the second floor. You know, in those

days, people were very, very frightened of polio as a children's contagious

disease, so I didn't certainly see any kids. I saw my brother and my sister

and I had a television. One of my great frustrations, of course, this is

before remote control, was that I wasn't able to get up to change the channel.

But I had my favorite shows. There was one called "The Children's Hour(ph),"

that Hornan Harduck(ph) used to do with lots of talented kids singing and

dancing. And I loved that. And some puppet shows.

GROSS: So did you have any sense at this age that you actually were getting

serious about movies?

Mr. COPPOLA: No, I didn't have a very, you know, important view of myself.

I was--you know, I had been always moved--many, many schools, so I always kind

of was a little bit of a loner and I had an extraordinarily talented and, you

know, really a kind of winner older brother who was very kind to me, but

pretty much was the star of the family. And so I never thought of myself

as--I wasn't good at school and I wasn't particularly as--you know, my family

was very good-looking, all of them, and you know, I was sort of the

affectionate one. I wasn't as good-looking as the others.

GROSS: Must have been interesting for you to eventually go from, you know,

being paralyzed for a year alone at home in bed, you know, to being such the

center of attention and so famous.

Mr. COPPOLA: It was totally an accident. It happened because I, you know,

sort of was a little bit of a boy scientist and I was very interest--I used to

stay up by myself in the basement of the garage, whatever--since we moved a

lot, whatever little shop I could set up. And it was my interest in science

and electricity and--you know, that got me kind of working on lights and on

theater, and then I think my older brother was a writer and because of him, I

heard about things related to literature and, you know, I pretty much wanted

to emulate him. So the combination of being interested in stories and

literature and lights and theater, and I must say girls--because the girls

were at the theater department, or the football team.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COPPOLA: So I wanted to--you know, I always was a little bit of an

outcast socially because I was the new kid, and I felt if I could hang out at

the theater and--of course, theater always needs volunteers, and if I was

willing to, you know, work and unravel the cable, or help build the sets, I

could be included in the group.

GROSS: Your father, Carmine Coppola, who wrote music for "The Godfather" and

for "The Restoration of Napoleon" was, you know, a professional musician

throughout his life, and certainly, you know, while you were growing up. He

was a flutist with an orchestra, he played for a while with Radio City Music

Hall, accompanying The Rockettes. What were some of the things that seemed

really exciting to you about his work?

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, you know, the most dramatic part of that period, as a

child, was that he was the solo flutist for Toscanini and the NBC Symphony

Orchestra. So all during the time that I was a small child, it was a very

prestigious, and occasionally there'd be articles in the newspaper about him,

and so we knew there was something important going on, although when I was

really little, I used to go around telling everyone that my father was a

magician, because I'd heard he was a magician, but I got it wrong. He was a

musician.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COPPOLA: I remember one incident that is very vivid in my mind. They

took me to the studio and--or radio--in RCA Studio 8H(ph), where the big

orchestra and Toscanini with his white hair and black turtleneck was, and I

was brought as a five-year-old in a little glass booth. And I was very

intrigued because there was a knob in the booth, and when you turned it all

the way to the left, you would hear the orchestra, and when you turned it to

the right, you couldn't hear the orchestra. I think that's when I first

realized as a concept that sound and picture are not necessarily connected.

GROSS: Two of your movies have been war movies, "Patton" and "Apocalypse

Now." Were you ever drafted?

Mr. COPPOLA: No, but one of my school experiences was at a military school.

I was at New York Military Academy and High School for a couple of years and,

of course, I played in the military band, but I was a full-out cadet, and so I

knew a lot about, you know, really, in a funny way, cadet life, which, of

course--it was a place--that place up there right next to West Point and I was

very good at drill and I knew all about military organization and stuff like

that.

GROSS: So you liked it.

Mr. COPPOLA: I did like it. After awhile I felt a little isolated there

when an older roommate graduated. He was someone who was, you know, reading

James Joyce, "Ulysses" and he was a kind of pretty interesting fellow. He was

also the only Jewish guy in the school, and I admired him. And the next year

I kind of felt very isolated and wanted to do interesting things with the

theater group there, and they didn't want me to, and I finally ran away.

GROSS: Ran away from school?

Mr. COPPOLA: Ran away from military school.

GROSS: Oh, my gosh. Were you caught?

Mr. COPPOLA: Well, I did it very effectively. I just called a cab.

GROSS: Well, what happened?

Mr. COPPOLA: I wandered around New York, scared to go home, because my

father was on the road with a Broadway show, with a touring show. And I

wandered around New York, and I had sold my uniforms to some guy whose brother

was going to come the next year, and I had a couple hundred dollars. And I

just sort of lived this very strange--wandering around New York and seeing

things I'd never seen before. And then when I got home to where my brother

was living with his wife, he said--I told him what had happened. He said,

`Here, read this book.' And I read "The Catcher in the Rye." And I said, `I

just did this.' I wrote a letter to J.D. Salinger after reading it and I

said in the letter, you know, `I'm 16 and I want to be a filmmaker, and I've

just lived something so much like your book that I know I would do a good job.

I wish you would please let me have the rights to make "Catcher in the Rye."'

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Oh, that's a scream. I'm sure you got a lot of response from J.D.

Salinger.

Mr. COPPOLA: Yeah, zero.

GROSS: Yeah.

CONAN: Terry Gross spoke with filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola in 1997.

Coming up, Lloyd Schwartz reviews "Three Mo' Tenors," the PBS broadcast and CD

featuring African-American tenors. We'll be back after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Three Mo' Tenors' CD and PBS show

NEAL CONAN, host:

First there were Three Tenors, then Three Irish Tenors. Now three

African-American performers, known as Three Mo' Tenors, are featured on a PBS

program airing this month. They also have a new CD. Classical music critic

Lloyd Schwartz recently went to a Three Mo' Tenors concert in Boston. He has

this review.

LLOYD SCHWARTZ reporting:

African-American women singers didn't have it easy getting into opera. Marian

Anderson broke the color barrier at the Met only in 1955. Since then, there's

been a steady stream of superstars, from Leontyne Price to Shirley Verrett, to

Jessye Norman. Black male singers have had an even harder time. And though

things are changing, they're changing slowly.

The telecast and CD of "Three Mo' Tenors," attempts to remedy that situation,

though the versatility of the three stars gets more emphasis than actual opera

singing, and frankly, only one of them excels in opera. The tenors are

Rodrick Dixon, Victor Trent Cook, who is nominated for a Tony award in "Smokey

Joe's Cafe," and the marvelous veteran, Thomas Young. He's so admired by

contemporary composers like John Adams and Anthony Davis that numerous roles

have been written for him; sometimes even more than one in the same opera. He

was chilling, for example, as both black Muslim spiritual leader Elijah

Muhammad and the seductive hustler named Street in Davis' "Life and Times of

Malcolm X."

Three Mo' Tenors mixes opera with Broadway, sizzling jazz, blues, soul--the

tenors do a terrific send-up of Gladys Knight & The Pips--gospel, and

spirituals. Crammed into an hour, the TV version doesn't have quite the free

spirit exuberance that got the small, but wildly enthusiastic audience singing

and clapping along when the tenors kicked off their tour in Boston. Still,

it's an entertaining, relatively ungimmicky hour. Even watching the rehearsed

participation of the audience at New York's Hammerstein Ballroom is fun,

though it's not as much fun as actually being there.

While opera gets short shrift, the shadow of one of the original Three Tenors,

Luciano Pavarotti, looms especially large in the programming here. Beginning

with the inevitable Three Tenors version of Verdi's most famous tenor aria.

(Soundbite of music)

THREE MO' TENORS: (Singing in Italian)

SCHWARTZ: There's also Pavarotti's theme song Puccini's "Nessun Dorma," which

Young sings with an unshowy seriousness. And the aria with the nine high C's

from Donizetti's "Daughter of the Regiment," the one that first brought

Pavarotti to international attention. Rodrick Dixon sings it accurately, but

not without effort. He's no serious competition for the master. His strong

voice is well suited for Broadway, though. The one show song left in the

telecast is the high-minded, but sentimental anthem, "Make Them Hear You" from

"Ragtime," which Dixon appeared in.

(Soundbite from "Three Mo' Tenors")

Mr. RODRICK DIXON (Three Mo' Tenors): The lyrics of the next song echo the

sentiments of African American tenors past, present, and future.

(Singing) Oh, I often tell the story, let it echo far and wide. Make them

hear you. Make them hear you. How justice was our battle and our justice was

denied. Make them hear you. Make them hear you. And say to those who blame

us for the way we chose to fight that sometimes there are battles that are

more than black or white. And I cannot put down my sword, when justice was my

right. Make them hear you. Go out and tell the...

SCHWARTZ: Victor Trent Cook, more a counter tenor than a tenor, is most at

home singing in a jazzy falsetto. His rendition of the spiritual "Were you

there" is too over the top to feel genuine. But his live wire, zoot-suited,

hip-swiveling impersonation of Cab Calloway in "Minnie the Moocher" is a

showstopper.

(Soundbite from "Three Mo' Tenors")

Mr. VICTOR TRENT COOK (Three Mo' Tenors): Hello! How ya doin' New York?

Unidentified Audience: Whoo!

Mr. COOK: We're so happy you came out tonight. This is a song made famous

by the late, great Cab Calloway.

A one, a two, a one, two, three and now here's a story about Minnie the

Moocher. She was a low-down hoochie koocher. She was the roughest, toughest

rail. But Minnie had a heart as big as a whale. Hidey, hidey, ho!

THREE MO' TENORS and Unidentified Audience: Hidey, hidey, ho!

Mr. COOK: Hidey, hidey, hidey, hidey, hey!

THREE MO' TENORS and Unidentified Audience: Hidey, hidey, hidey, hidey, hey!

Mr. COOK: Ohh, ayy!

THREE MO' TENORS and Unidentified Audience: Ohh, ayy!

Mr. COOK: Ah doo-bah, dee-bah, doo-bah, day.

THREE MO' TENORS and Unidentified Audience: Ah doo-bah, dee-bah, doo-bah,

day.

(End of soundbite)

SCHWARTZ: On stage Three Mo' Tenors was primarily, and rightly, a showcase

for Thomas Young's phenomenal versatility. He's the real artist. On TV he's

more like one of the guys. There's still a glimpse of his wide range, though,

which encompasses, along with opera, "America the Beautiful," astonishing

scat, and his own arrangement of Annie Ross and Wardell Gray's deranged

"Twisted."

(Soundbite of "Twisted")

Mr. THOMAS YOUNG (Three Mo' Tenors): (Scatting)

(Unintelligible) told me that I was right out of my head...

SCHWARTZ: Three Mo' Tenors is the brainchild of Marion J. Caffey, who starred

as Jelly Roll Morton on Broadway. His official bio says he is now, quote,

"completely dedicated to conception, writing, and directing." I hope his

future conceptions include lots more Thomas Young.

CONAN: Lloyd Schwartz is classical music editor of The Boston Phoenix and

director of the creative writing program at the University of Massachusetts,

Boston. He reviewed the Three Mo' Tenors' CD and their concert, which is

being broadcast this month on the PBS "Great Performances Series."

For Terry Gross, I'm Neal Conan.

(Soundbite of song)

Unidentified Chorus: Are you ready for your miracle?

THREE MO' TENORS: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah! Here we are. Let's get up on the

floor. Leave all your problems on the outside. Jesus was born with the Holy

Ghost fire. Open up your mouth and lift the name of Jesus higher.

(Credits)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.