Doug Sahm's '60s Quintet

Few musicians are as identified with Texas as the late Doug Sahm. But Sahm also spent five years in exile in California, where rock historian Ed Ward got to know him. Ed takes a look at this period, in which he says Sahm and his band, the Sir Douglas Quintet, did some of their most lasting work.

Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on May 25, 2006

Transcript

DATE May 25, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

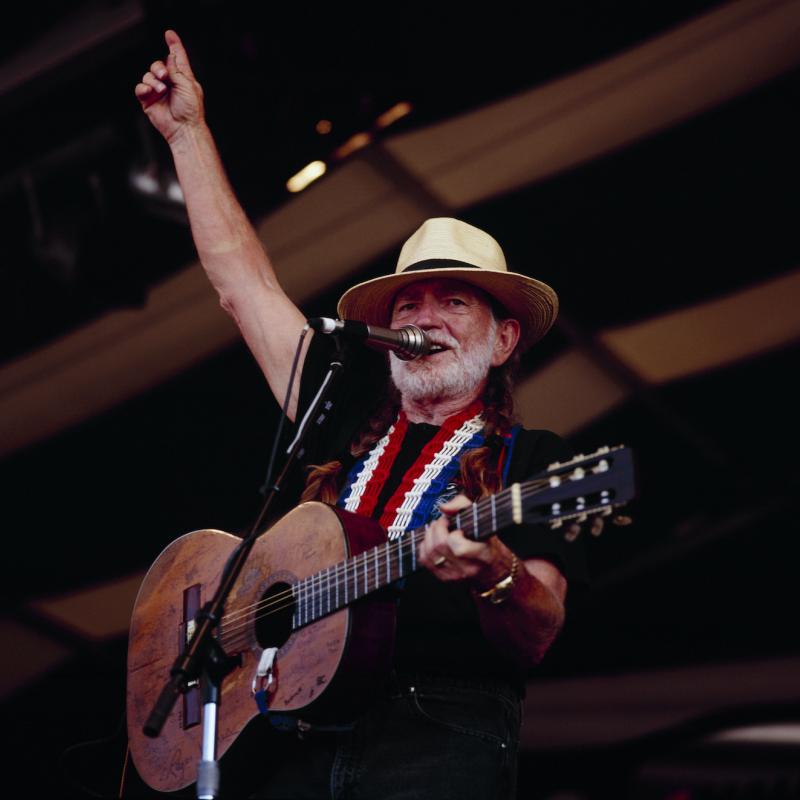

Interview: Willie Nelson talks about his new book "The Tao of

Willie" and his music

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Willie Nelson has written over 2,500 songs. We're going to talk about just a

few of them. The occasion for his visit is his new book, "The Tao of Willie,"

which he describes as his way of sharing a little of what he's learned in his

72 years of making music and friends. Nelson is famous for many things, from

writing songs like "Crazy," "Night Life," "Hello Walls," and "Funny How Time

Slips Away," to organizing farm aid and touring on his bus powered by

biofuels. Three of his CDs from the '70s--"Shotgun Willie," "Phases and

Stages" and "Live at the Texas Opry House"--will be released with extras next

month in a collection called ""The Complete Atlantic Sessions." It includes

this song, "Local Memory."

(Soundbite from Willie Nelson's "Local Memory")

Mr. WILLIE NELSON: (Singing) "The lights go out each evening at eleven, and

up and down our block, there's not a sound. I close my eyes and search for

peaceful slumber, and just then the local mem'ry comes around. Piles of blues

against the door make sure sleep will come no more. She's the hardest working

mem'ry in this town. Turns out happiness again and then lets loneliness back

in, and each night the local mem'ry comes around. Each day I say tonight I

may escape her. I pretend I'm happy and never even frown. But at night I

close my eyes and pray sleep finds me, but again the local mem'ry comes

around. Rids the house of all good news, then sets out my crying shoes. What

a faithful mem'ry never lets me down. We're both up till light of day,

chasing happiness away. And each night the local mem'ry comes around."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Willie Nelson, a track from his album "Shotgun Willie," and

that's one of three albums about to be reissued on "Willie Nelson: The

Complete Atlantic Sessions."

Willie Nelson, welcome back to FRESH AIR. It's such a pleasure to have you

back.

Mr. NELSON: Thank you very much. Good to be back.

GROSS: You know, there's a couple of people who have been on FRESH AIR in the

past year who talked about how you changed their lives. And one of them was

the songwriter and singer Billy Joe Shaver, who talked about how you helped

him the day his son died. What he said was he was told his son died in a

heroin overdose but Shaver says that his son had fallen in with some bad

companions, and he wasn't sure what really happened. And I want to play an

excerpt of the tape here. I'd like you to hear this. In this part, Shaver

told me the police took him to the hospital where his son was, and I'll let

Billy Joe Shaver take the story from here. It's the story of the day of his

son's death and how you helped him.

Mr. BILLY JOE SHAVER: I don't know what happened. I really still to this

day don't know what happened, and I tried to stay in there with him while they

were checking him to see if he was brain dead, and the police ran me off and

they wouldn't let me back in. Told me they were going to arrest me. Oh, my

God! And Willie Nelson--I've got to give him credit--he's the one that talked

me back out into the world. He said, `Come on, Billy.' He says, `You're

supposed to play tonight. It's New Year's night.' He said, `I'll throw

something together.' And Willie stayed up there and played all night long and

I'd go up and sing every once in a while.

I owe Willie a lot. He's been such a good friend. And he took me down to his

house, and we spent the night there and hadn't talked in quite a long time.

And he told me a lot of things because he knew a lot. He's a wise man, and he

gave me some money. And you know it's hard to be broke when you're in a

situation like that, and then he paid for my son's burial. I didn't have any

money at the time.

GROSS: Mmm.

Mr. SHAVER: I later got some money from Sony and tried to pay him back, and

he wouldn't take it.

GROSS: That was Billy Joe Shaver on FRESH AIR, the songwriter and singer, and

my guest is Willie Nelson.

Willie Nelson, when Billy Joe Shaver told that story, he talked about how on

the day his son died, you got together a band, and they simply forced him to

perform that night. It made me wonder if part of the reason that you did that

was because you thought the stage was the only safe place for him that night

because it sounds like he was so upset about his son's death that he might

have, like, drunk himself into a bad place or done something, taken some

action that he might have lived to regret.

Mr. NELSON: Well, I always find that on the stage is the safest place for

me, no matter what I've been into. If I get up there for a couple of hours, I

can sometimes work it out. Most of the time during the show I can sort of

clear my mind of whatever, so I knew that at this particular time, Billy Joe

needed to be working. This wasn't a good time to be laying around thinking

about things.

GROSS: So, how do you put together a concert? On the night of his son's

death--I mean, what kind of music seemed appropriate for him and for you? I

don't know if you even remember.

Mr. NELSON: Oh, I do remember very well, and it wasn't the music. It wasn't

anything out of the ordinary. I did some of my songs, and then occasionally

Billy Joe would come up and do one of his, but it was mainly the fact that we

were out there, we were at this club, and we were trying to make the best of a

really bad situation, and I figured that that was the best way that I could

help Billy Joe was just to get him back on the stage, singing and playing and

sort of living in the moment again and forgetting about what just happened if

he could.

GROSS: Did the audience know what had happened?

Mr. NELSON: I think most everyone there knew what had happened, and they

were happy to see Billy Joe there because they also knew that this was where

he needed to be, out with friends, fans, rather than trying to hole up

somewhere.

GROSS: I figure you must have known something about what Billy Joe Shaver was

going through because you lost a son, too. Did you perform after that? Did

the stage seem like the best place for you?

Mr. NELSON: Yeah, right after my son died, I had a gig booked in Branson,

Missouri, and it was around New Year's Eve, and he died on Christmas. So it

would have been really easy for me to cancel and go off somewhere and you

know, grieve alone somewhere for month or a long time. I could have done it.

It was--it would have been the easiest thing to do. But I didn't. I just

knew instinctively that my best place to be was somewhere on the stage. And

it just so happened that I had a six-month gig there in Branson, Missouri, so

I had six months, and I think it was the best place for me, especially at that

time.

GROSS: You have so many great records, it was really hard to narrow down what

songs I wanted to play during your FRESH AIR visit today, but here's one I

know I want to play. There's a great album that came out, oh, about three

years ago called "Crazy: The Demo Sessions," and it's demo recordings that

you made after you were a DJ, when you got to Nashville, and these are--some

of them are from the early 1960s. This one is. It's from 1961, and the song

is called "Opportunity to Cry." It's just voice and guitar. Do you remember

making this?

Mr. NELSON: Sure. Was this the cut that we did in Nashville? Or is this a

later cut?

GROSS: Well, you know on the liner note, I think it says that all they know

is that--they think it's recorded in your office.

Mr. NELSON: It probably was because I did a lot of recording downtown--or

not--actually it was out in Goodrichville, a place called Pampered Music,

where the publishing company was. And I did a lot of writing and playing,

sitting around in a garage back there that had been converted into a studio.

So that's probably where I was.

GROSS: OK. Let's hear it. This is Willie Nelson, recorded in 1961. It's a

demo of his song "Opportunity to Cry."

(Soundbite of "Opportunity to Cry" by Willie Nelson)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "Just watch the sun rise on the other side of town.

Once more I've waited and once more you've let me down. This would be a

perfect time for me to die. I'd like to take this opportunity to cry. You

gave your word, I'll return it to you with this suggestion as to what you can

do. Just exchange the word `I love you' to `Goodbye' while I take this

opportunity to cry. I'd like to see you but I'm afraid that I..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Willie Nelson and a demo recording he made of his own song in

1961 when he was trying to interest people in recording his songs.

What was the fate of that song? Did anybody ever do it?

Mr. NELSON: I don't think everybody--anybody done it but me. I've recorded

it maybe a couple of times since then on, you know, various, a couple

different albums. I don't remember what they were right at the moment, but it

was one of those really sad, almost pitiful songs.

GROSS: In your new book, you write, `I've always had my own way of singing,

and it was nothing like the way other Nashville stars sang.' What did people

think of your singing on the demo before you recorded yourself?

Mr. NELSON: Well, I think a lot of the musicians understood what I was doing

and my phrasing was a little different and my chords were a little strange,

too. They weren't your normal three-chord country songs, and that was a

little strange for a lot of the people in the industry at that time because

country and pop hadn't really melted together like they have today in some

instances. So a song with a lot of chords in it wasn't considered to be that

commercial. So I had fun trying to get those songs done in that kind of

atmosphere.

GROSS: When you said that your singing was different and your chords were

different, do you think that the chords and the singing were more

jazz-inflected in some ways, and had you listened to a lot of jazz?

Mr. NELSON: Well, I have listened to a lot of different kinds of music and I

grew up listening to everything from Frank Sinatra to Hank Williams, so I'm

sure I picked up a lot from, you know, every one of those guys. I lived

across the street from a whole gang of great Mexican friends of mine who

played music all the time, so I was influenced by all that music. I worked in

the fields with all kinds of people who sang and played in practically every

language from Bohemian to Czechos to Spanish, so I heard all kinds of music.

It was like being in an opera out there in the cotton fields and hearing all

that music coming at you all day long. So it was--picking cotton wasn't all

that fun but the music out there was incredible.

GROSS: Did you sing when you were picking cotton?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, at the top of my voice.

GROSS: Yeah. What would you like to sing?

Mr. NELSON: Well, I would sing what they were singing, you know. I'd--they

would be singing over there singing some blues, and I would sing some blues

with them. I had no idea what I was doing but I was trying to sing and I

would sing songs that I knew back then. I didn't know many songs other than

gospel songs back then. I'd sing "Amazing Grace" and songs like that.

GROSS: My guest is Willie Nelson. He has a new book called "The Tao of

Willie." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Willie Nelson.

Now in your new book "The Tao of Willie," you say you wrote your first

cheating song when you were seven, long before you knew firsthand anything

about broken hearts and cheating. When you started writing songs when you

were older, did you know anything about, like, the structure of a 32-bar

bri--song or what a bridge was like, you know, how to write the bridge to a

song? Did you think of the song in technical terms when you started seriously

writing them?

Mr. NELSON: No, I never did and I still really don't. I just kind of write

and sing and--of what I feel like writing, and my timing is pretty good so I,

you know, don't break meter that much, and ear is pretty good so I don't play

a lot of wrong chords. But you know, as far as the lyrics and the singing

itself, everybody has to judge that for themselves, but back in those days I

was writing about things I had, you know, like you say, at that age I couldn't

have possibly known what I was writing about, unless you happen to believe in

reincarnation, which I do. And I probably--I come here knowing some things

that I wrote about before I knew I knew.

GROSS: You know, in talking about country songs, like country songs have

certain conventions in a way. You know, a lot of country songs are about

cheating or drinking too much or falling in love. I guess you could say the

same thing about rock songs, but there's also like a subcategory of country

songs where like you're feeling so bad, you're just overwhelmed with

self-pity, and one of the most self-pitying of the self-pitying songs is a

song that you wrote that's included on your demo sessions that I really want

to play and hear the story behind, and so here it comes. This is Willie

Nelson singing a very self-pitying song.

(Soundbite of a Willie Nelson song)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "If I only had one arm to hold you, better yet if I

had none at all. Then I wouldn't have two arms that ached for you, and

there'd be one less memory to recall. If I'd only had one ear..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: And then in the next verse, you imagine only having one eye, so you'd

have only one eye to cry. Did you think...

Mr. NELSON: That's pitiful, isn't it?

GROSS: Yes, so self-pitying. Did you think that--when you sat down to write

this, that you would write the ultimate self-pitying song?

Mr. NELSON: Actually, I didn't sit down to write that one. The way that

song happened, I was lying in bed with Shirley, and I woke up in the middle of

the night wanting a cigarette and her head was on my arm, so I had to reach

over on the side of the bed and get a cigarette and put it in my mouth and

then get a match with that one hand and then try to strike that one match. So

it all started from that.

GROSS: Oh, because you only had one arm. Really? Is this really what

happened?

Mr. NELSON: It's true. That's a true story. And so from the one arm, I

went into the one eye, one ear, one leg.

GROSS: That's really funny. And what was the fate of this song?

Mr. NELSON: I recorded it a couple of times. Other people have recorded it.

Merle Haggard recorded it, I think. George Jones did. So it's got a pretty

good history.

GROSS: Now you have a very recent CD, I guess I could call it a new CD, of

songs by Cindy Walker who's most famous for "You Don't Know Me" and "Bubbles

in My Beer." Did you know her well? She died just at about the time your CD

was released.

Mr. NELSON: Yeah, and at the time we started doing this album I'd, yeah, I'd

known her a long time. She was a very good friend, and I had talked to her

and we'd talked about doing an album of her songs for years. And she had sent

me songs, and I had quite an accumulation of Cindy's songs, and I knew a lot

of them. But I just hadn't got into the studio to do it for one reason or

another. And I'm glad I did it when I did because Cindy's health was

deteriorating pretty well at that time, and I was just hoping that I could get

the album completed and out while she was still here to listen to it. And as

it happened, she did get to hear it before she died.

GROSS: What did she have to say?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, she loved it. She called me up and told me, you know, lot

of great things about how she enjoyed it. And she really made me feel good

about getting it done.

GROSS: I'd like to play a song from that CD, and I'm going to give you your

choice of one of her two most famous songs, "You Don't Know Me" or "Bubbles in

My Beer."

Mr. NELSON: Well, you know "Bubbles in My Beer" is a great up-tempo song

that I had first learned from Bob Wheels and the Texas Playboys. I had no

idea who wrote the song when I started singing it. But I was a huge Bob

Wheels fan, and I just tried to sing and play every song that they recorded,

so when "Bubbles in My Beer" came out, it was a natural because I was, you

know, a beer joint operator--I mean, beer joint club player, so naturally it

was a good song where I would play it, and it still is. It's a great piece of

literature. So let's play "Bubbles in My Beer."

GROSS: Good enough. And this is from Willie Nelson's CD of songs by Cindy

Walker.

(Soundbite of "Bubbles in My Beer" by Willie Nelson)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "Tonight in a bar alone I'm sitting, apart from the

laughter and the cheer. While scenes from the past rise before me just

watching the bubbles in my beer. And I'm seeing the road that I've traveled,

a road paved with heartaches and tears. And I'm seeing the past that I've

wasted while watching the bubbles in my beer. A vision of someone who loved

me brings a long silent tear to my eye. As I think of a heart that I've

broken And of the golden chances that have passed me by. Oh, I know that my

life's been a failure, and I've lost everything that made life dear. And the

dreams I once dreamed now are empty, as empty as the bubbles in my beer."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Willie Nelson will be back in the second half of the show. His CD of

Cindy Walker songs is called "You Don't Know Me." His new book is called "The

Tao of Willie."

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "Bubbles in My Beer" by Willie Nelson)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "A vision of someone who loved me brings a long silent

tear to my eye. As I think of a heart that I've broken And of the golden

chances that have passed me by. Oh, I know that my life's..."

(End of soundbite)

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR.

I'm Terry Gross back with Willie Nelson. He has a new book called "The Tao of

Willie." Three of his CDs from the '70s--"Shotgun Willie," "Phases and Stages"

and "Live at the Texas Opry House"--will be released next month on a

collection called "The Complete Atlantic Sessions." From the live recording,

here's Nelson singing a song he cowrote with Waylon Jennings.

(Soundbite of song by Willie Nelson)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "A longtime forgotten are dreams that just felt by the

way. And the good life he promised ain't what she's living today. But she

never complains of the bad times or the bad things he'd done. She just talks

about the good times they've had and all the good times to come. She's a

good-hearted woman in love with a good-timin' man. She loves him in spite of

his ways that she don't understand. And throughout teardrops and laughter,

they going to pass through his world hand in hand. This good-hearted woman in

love with a good-timin' man."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: In your new book, "The Tao of Willie," you write in praise of

marijuana. You write, `The highest killer on this planet is stress and there

aren't many people in America who don't medicate themselves one way or

another. Some people choose an occasional beer or a little pill the doctor

prescribes, and I'm not knocking that, but the best medicine for stress is

pot.' Then you go on to say that alcohol and a lot of prescription drugs don't

agree with you but marijuana does. Are you afraid to talk that way, afraid

that, like, you'll be busted.

Mr. NELSON: Oh, I have been busted, more than once, you know, it's just,

minor amounts, so, a fine, whatever. It's--there was a time, though,

especially in the state of Texas when a couple of C's could get you life. But

things have lightened up a little bit. You have people out there who are

sharper now who realize that that there's a slight difference between

marijuana and heroin. But the fact that you can use it for fuel--I drove a

Cadillac across Kentucky one time on hemp oil.

GROSS: You're full of surprises when it comes to biofuels. What are you

driving with now?

Mr. NELSON: I think we're driving soybeans right now. I think we buy

biodiesel wherever we can find it, and usually most of the biodiesel that we

find is made from soybeans.

GROSS: How did you start doing that? Like using alternative fuels?

Mr. NELSON: My...

GROSS: It's become one of the things that you're famous for.

Mr. NELSON: It hadn't been that long ago, maybe three years ago, my wife

came to me and said, `I want to buy this car that runs on biodiesel,' and I

said, `What the hell is that?' And she said, `Well, it's vegetable oil.' And I

thought she was--you know, been on that Maui-wowie again, you know, so I

said--I said, `You better make sure you're right on this one.' She bought a

brand-new Volkswagen Jetta, and she--there's a business on Maui and has been

for many years now where they go around to all the restaurants and they

collect the grease from the grease traps and they recycle it and turn it back

into 100 percent pure vegetable oil, and you can put it right into your diesel

car. So she bought her car, I drove it, the tailpipe smelled like french

fries. I said, `Wait a minute. We may be onto something here.'

So I bought a Mercedes, a brand-new one, and I filled it right up with

vegetable oil, and I think the Mercedes people shuddered a little bit when

they first heard about that because they wasn't sure themselves what this

would do to their $60,000 automobile, but it has run perfectly, it runs

cleaner, I get better gas mileage. You know, the president said we're

addicted to oil. I don't think we're addicted. I just think that's the only

thing we have had. So we're glad to find alternatives. So along with ethanol

biodiesel, your hydrogen, your windmills, all these different ways of making

fuel combined, will help us reduce our dependency on foreign oil.

GROSS: Now the last couple of summers you've been touring minor league

baseball parks with Bob Dylan. Are you going to do that this summer, too?

Mr. NELSON: No, actually I'm working with Fogerty through the summer and

we're working some...

GROSS: With John Fogerty?

Mr. NELSON: Yeah. We worked a couple of years there in a row with Bob

Dylan, and we did work a lot of those minor league ballparks which has turned

out to be a great idea.

GROSS: What do you feel you and Bob Dylan have most in common? As friends or

songwriters or lovers of music?

Mr. NELSON: Well, I think all those things. He enjoys touring and playing

probably as much as I do because I--he's always out here somewhere. And I

enjoy his friendship because he's a great guy. He's a little shy and reserved

but, you know, so am I in a lot of ways, so I understand that. We've written

a song together one time. We wrote a song called "The American Dream," and it

was written in sort of a different way, I guess, because he sent me the

melody, a track that he'd already recorded where he just hummed a melody, and

so the whole thing was like `hm-hm-hm-hm-hm-hm-hm.' So it was kind of a

strange demo but the track was great, so I wrote lyrics to the--to his

instrumental, and it turned out, I thought, pretty good. We recorded it here

in New York, maybe just a month or so after we finished it.

GROSS: My guest is Willie Nelson. Here he is with Bob Dylan, singing

"Heartland," which they co-wrote.

(Soundbite of "Heartland" by Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "There's a home place under fire tonight in the

heartland. And the bankers are taking my home and my land from me. There's a

big gapin' hole in my chest now where my heart was. And a hole in the sky

where God used to be."

Mr. BOB DYLAN: (Singing) "There's a home place under fire tonight in the

heartland, with a well where the water's so bitter nobody can drink. Ain't no

way to get high and my mouth is so dry that I can't speak. Don't they know

that I'm dyin' why ain't nobody crying' for me."

Mr. NELSON and Mr. DYLAN: (Singing in unison) "My American dream fell apart

at the seams. You tell me what it means, you tell me what it means."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: We'll continue our interview with Willie Nelson after a break. This

is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Willie Nelson. He has a new book called "The Tao of

Willie."

I want to ask you about somebody else who you were very close to, and that's

Johnny Cash. You knew him for years, you played together, and "The

Highwayman." How would you describe him as a friend?

Mr. NELSON: Well, a friend is a friend. You know, a friend is with you

through good or bad any time, so John and I have always been friends.

Whenever--you know, he'd call me up several times whenever he was having a bad

day just to hear a joke, and so I'd tell him the latest dirty joke, and I'd

try to make it as dirty as possible so he would laugh louder.

GROSS: You actually must collect jokes because your new book is filled with

jokes, literally jokes.

Mr. NELSON: Well, I believe in jokes, you know. Jokes are important, a

necessity. You need to laugh at yourself, other people, life, death. You

need to figure out a way to laugh at everything.

GROSS: Do you tell a lot of jokes on stage?

Mr. NELSON: No, I don't tell any jokes on stage.

GROSS: How come?

Mr. NELSON: I'm afraid that if I quit singing, people will leave. I don't

think they came to hear me tell jokes.

GROSS: That's funny. Did someone in your family tell jokes when you were

growing up.

Mr. NELSON: You know, that was, you know, our entertainment. That was

before TV. We'd just sit around and tell jokes to each other and play

dominos, and tell more jokes and play dominos.

GROSS: And sing too?

Mr. NELSON: And sing, yeah.

GROSS: Did the family sing together?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, yeah. My grandfather was a great singer and my grandmother

sang. My mother and dad were both singers, too. But I sang quite a bit in my

early life with my sister. We played the guitar and piano, and I would sing.

My--but, you know, my grandfather died when I was six years old. So after

that, we'd sit around and play piano, and my grandmother would teach sister

how to play the piano. And I'd sit there on the piano stool and try to learn

the chords along with her as she was reading the music.

GROSS: You know, for some of us, singing is an incredibly self-conscious

experience. It must be so natural to you having grown up in a house where

what people did was they got together and they sang together.

Mr. NELSON: Yeah, it is natural. And they were voice teachers, so, you

know, we talked about singing...

GROSS: Who? Your parents? Your parents were voice teachers?

Mr. NELSON: Yeah, my grandparents--they were great voice teachers, and my

grandmother was great in teaching you deep breathing and breathing, singing

from way down in the diaphragm, and these were just natural things that we

were taught growing up, was how do you breathe and the better your lungs are,

the more you can hold a note and the more control you have.

GROSS: Wow? So you didn't even have to break bad habits. You just started

off with the right ones.

Mr. NELSON: I was--I was a very fortunate young guy.

GROSS: How did your grandparents communicate breathing from the diaphragm

when you were a child?

Mr. NELSON: Well, they just said, `Breathe from the diaphragm.' And then

they would hold their hand down around their lower abdomen there where I

suppose that's where your diaphragm is, and so I would sing from as low down

there as I could.

GROSS: I want to ask you a little bit. You know, your new book is called

"The Tao of Willie," referring to the Tao-te-ching which is, you know, an

ancient book of Chinese wisdom. I think the first song that you ever sold was

"The Family Bible." Do I have that right?

Mr. NELSON: Right. Right.

GROSS: So, you know, the Bible has literally played a role in your

songwriting career. What kind of role did it play, like, in your home growing

up?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, you know, it was a great role that it played. My

grandparents were huge gospel singers and writers, and they--Sunday School

teachers and they, you know, always had gospel music, singing it and playing

it, listening to it on the radio, singing it in church. And the Bible was

there, and it was read all the time. I turned--I was a Sunday School teacher,

so I, you know, started reading the Bible more and more and teaching it in

class. So, yeah, I grew up reading the Bible.

GROSS: And has it inspired any songs other than "The Family Bible"?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, I don't--I guess, probably, maybe in some way or another.

Maybe it inspired all songs. I believe every song is gospel, so everything I

write I hope is gospel.

GROSS: How did you start reading books of Chinese wisdom and start

meditating?

Mr. NELSON: One of the things that I was wondering about in--when I was

going to church and teaching Sunday School was I knew that I was a Christian

but I knew that there was millions of people out there who were other

religions, and I wanted to find out about those other religions, so I did a

lot of research in the Bible--I mean, in the library and read about different

religions. I read about all the religions I could find and also read things

by Kahlil Gibran, Edgar Cayce, and they talked about reincarnation, and it

made so much sense to me to believe that, you know, this one time through,

there's no way you could get it right. It's kind of like going to school.

You pass the first grade, you go to the second grade, and I--you know, I'm

probably somewhere around the fourth grade, right now, still coming back, and

so I believe that's the only thing that makes sense, that you do get a chance

to come back. It's not a chance, you are forced to come back and learn the

lessons that you didn't learn the last time.

GROSS: Let me bring this back to your songwriting. Are you still writing a

lot of songs?

Mr. NELSON: I'm probably writing a quantity as many as I--well, back in the

'60s I was writing a whole lot more songs than I do now. But I still write,

you know, a few songs every year.

GROSS: And...

Mr. NELSON: I have a new song now. The one I just wrote now sort of goes

along with the book. It's called "It's Always Now," and "nothing really goes

away and everything's here to stay and it's always now."

GROSS: When you write songs, are you sitting down and working in a

craftman--craftsman-like way on a song or are they just kind of coming to you

while you're doing things?

Mr. NELSON: It used to when I was driving myself to different gigs around

the country, I would do a lot of writing just driving down the highway. And I

still think, you know, that that's the best way for me to write. I can get in

my car, I believe, and take off driving and head anywhere and start thinking

about something, and then if I'm--if I'm lucky, I'll write a song, but I have

to get somewhere by myself to do it. There's a lot of things going on, a lot

of interruptions and things, that makes it difficult to do and just, you know,

riding the bus.

GROSS: And what about writing the music part, like the chords for instance.

Do you need a piano or a guitar when you do that?

Mr. NELSON: If there's a guitar or piano around, I would use it, but I can

usually write it all in my head, and then I'll get a guitar when I find one

and go over the lyrics and the melodies and probably wind up changing it

several times before I finally decide this is the way I want it.

GROSS: But from what you said before, it sounds like--I mean, do you ever

like actually write it down?

Mr. NELSON: I do now more than I used to. I used to have this theory that,

`Well, if you don't remember it, it ain't worth remembering,' but later on in

life, I figured out, `Well, maybe I--maybe I should jot down this one because

I don't want to forget it.'

GROSS: Willie Nelson, it's been a pleasure to talk with you. Thank you very

much.

Mr. NELSON: Well, thank you. It's nice to talk to you again.

GROSS: Willie Nelson's new book is called "The Tao of Willie."

(Soundbite of "Crazy" by Willie Nelson)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing) "Crazy, crazy for feeling so lonely. I'm crazy, crazy

for feeling so blue. I knew you'd love me as long as you wanted, and then

someday, you'd leave me for somebody new. Worry, why do I let myself worry?

Wonderin' what in the world did I do? Crazy..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Coming up, rock historian Ed Ward on Doug Sahm and what happened when

this Texas musician showed up in San Francisco just in time for the summer of

love.

This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Rock historian Ed Ward discusses Doug Sahm, a Texas

musician from the 1960s

TERRY GROSS, host:

Although few musicians are as identified with Texas as the late Doug Sahm, he

also spent five years in exile in California where rock historian Ed Ward got

to know him. Ed takes a look at this period in which he says Sahm and his

band, the Sir Douglas Quintet, did some of their most lasting work.

(Soundbite of music by Sir Douglas Quintet)

Unidentified Singer #1: (Singing) "When there's nothing left to say and all

the clouds have faded away and my mind wanders out across the bridge, just to

be there in the morning with the sun coming through the trees, well, you know

there's no other place I'd rather be. Sunday, sun and me, valley blue days,

you can feel the magic in the air."

(End of soundbite)

Mr. ED WARD: Doug Sahm was doing just fine as 1966 started, with two hit

records with the Sir Douglas Quintet under his belt and as much work as he

could handle. But it all came crashing down at the Corpus Christi airport

when he was busted for pot. Fortunately, he had a good lawyer and a parole

officer who let him serve his sentence in California, and within months, Doug

joined the Texas diaspora to San Francisco. He'd been preceded by a lot of

other folks: Chet Helms, who started the Family Dog concert promotion

business; Bob Simmons, who was helping longtime San Francisco DJ Tom Donahue

start underground FM radio; cartoonist Gilbert Shelton; and numerous

musicians, including Janis Joplin. Doug felt at home and with a new record

deal in hand, set about assembling some new musicians to help him make a

record. As always, Doug had huge ambitions and put together a big band with

horns to help him realize them. In reality, they weren't too different from

the rhythm and blues bands he'd played with as a teenager in San Antonio.

(Soundbite of music by Honkey Blues Band)

Unidentified Singer #2: (Singing) "Never get to big, you sure don't get too

heavy. Don't have to...(unintelligible) blues sometime, yeah. You never get

to big, you sure don't get too heavy. Don't have to...(unintelligible) blues

sometime, yeah. Seems people just don't talk no more. (Unintelligible).

Something I just found out, some things you just can't do without."

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WARD: He called them the Honkey Blues Band and the music they played

wasn't exactly what San Francisco was used to hearing in 1968. He did

however, manage to write one psychedelic gem, very much part of the time and

place.

(Soundbite of music by Honkey Blues Band)

Unidentified Singer #3: (Singing) "The song of everything has something for

somebody. The song of everything has something for somebody. Spend my life

in ecstasy, underneath the redwood trees. It knocks you to your knees. When

you're there, breath air. (Unintelligible)...if you're there. And you know

it's the beat...(unintelligible)."

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WARD: Although Rolling Stone compared it to finding a cheeseburger in

your medicine cabinet, the Honkey Blues album sank like a stone. The record

company wanted another album, and Doug reunited the quintet in the Bay area.

With Augie Meyers' fabled organ back in the sound, Doug found another groove,

one which produced a masterpiece.

(Soundbite of music by Sir Douglas Quintet)

Unidentified Man: The Douglas Quintet is back. We'd like to thank all of our

beautiful friends all over the country and all the beautiful vibrations of

love.

Unidentified Singer #4: (Singing) "Teeny Bopper, my teenage lover, I caught

your waves last night. It send my mind to wonderin'. You're such a groove,

please don't move. Please stay in my love house by the river. Fast talkin'

guys with strange red eyes have put things in your head and started your mind

to wonderin'. I love you so, please don't go. Please stay here with me in

Mendocino. Mendocino, Mendocino, where life's such a groove, you blow your

mind in the morning. We used to walk through the park, make love along the

way in Mendocino."

Man: Ah, play it, Augie!

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WARD: "Mendocino" was also a big hit in Europe, which gave the quintet a

new audience. Furthermore, the album was devastating, filled with Doug's

homesickness and heartbreak.

(Soundbite of music by Sir Douglas Quintet)

Unidentified Singer #5: (Singing) "I left my home in Texas, headed for the

Frisco Bay, counted a lot of hard time through changes all the way. Now I'm

up here...(unintelligible)...wonderin' where I ought to be. And I wondered

what happened to...(unintelligible)."

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WARD: As usual, Doug was going a mile a minute, and he rushed the

quintet back into the studio to record another album immediately. "Together

after Five" wasn't a success despite reuniting the quintet with Huey Meaux,

their original producer.

Late in 1970, he moved to Prunedale, a tiny village near Monterey, right smack

in the middle of the United Farm Workers Union dispute with the lettuce

farmers. There he discovered and produced a remarkable band called Louie &

the Lovers, which sounded like a Chicano California version of the quintet.

(Soundbite of music by Louie & the Lovers)

Unidentified Singers: (Singing in unison) "Rise...

Unidentified Singer #6: (Singing) ...to the sounds of my leaving, won't say

goodbye.

Singers: (Singing in unison) Run...

Singer #6: (Singing) ...yes, my arms weeping, please dry my eyes.

(Unintelligible)...stay, but now you told me to leave, darling, I just can't

stay."

(End of soundbite)

WARD: But in 1971 things in Texas mellowed out, and Doug left California for

Austin. There he produced more great music, although he'd never again have

the commercial success he had with "Mendocino."

GROSS: Ed Ward lives in Berlin.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of music)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.