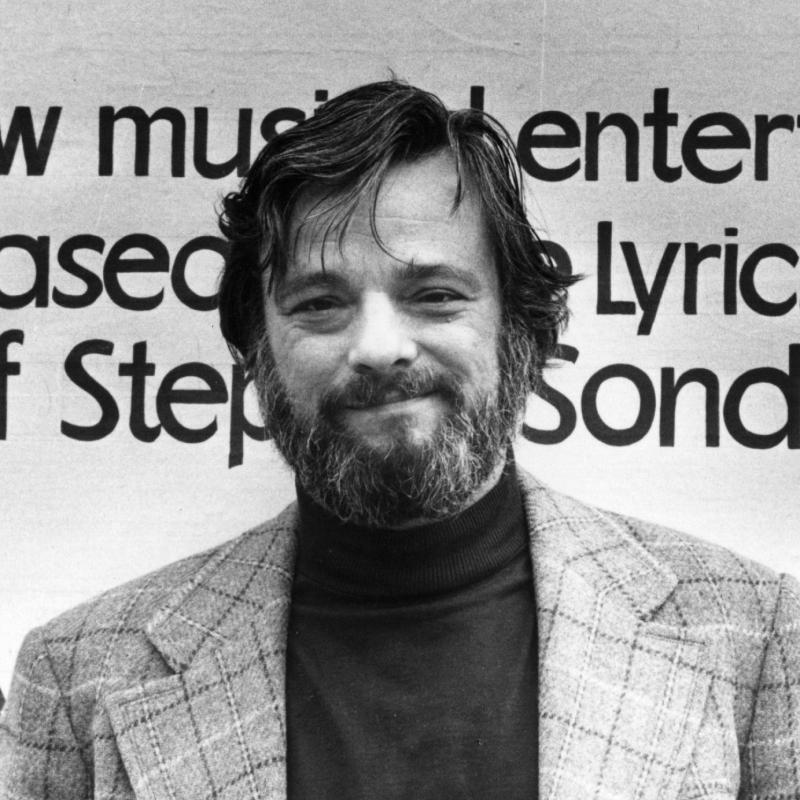

Composer and Lyricist Stephen Sondheim Returns to Fresh Air.

Composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim. He was mentored by Oscar Hammerstein, and went on to revolutionize musical theatre. His first major success was writing lyrics for “West Side Story.” Sondheim wrote the lyrics for “Gypsy.” He composed the music and wrote the lyrics for “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” “Follies,” “A Little Night Music,” “Sweeny Todd,” “Sunday in the park with George,” and “Into the Woods.” In 1954 he wrote the musical “Saturday Night” but it wasn’t performed for 40 years. There’s a new cast recording of it.

Other segments from the episode on September 14, 2000

Transcript

DATE September 14, 2000 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Stephen Sondheim, composer and lyricist, discusses

his career

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest is the most important composer writing for the theater today, Stephen

Sondheim.

(Soundbite of music from "Saturday Night")

GROSS: You're listening to the overture from Stephen Sondheim's first

musical, "Saturday Night." He wrote it in the mid-'50s, before writing the

lyrics to "West Side Story" and "Gypsy," before writing words and music for "A

Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum," "Company," "Follies," "A Little

Night Music," "Sweeney Todd," "Sunday in the Park With George," "Into the

Woods" and "Passion."

Although Sondheim expected to make his Broadway debut with "Saturday Night,"

it wasn't staged until 1997. In the interim, this neglected musical became

something of a legend. Singers who love Sondheim managed to get their hands

on some of the songs from the show and performed them. Now we can finally

hear all the songs, as recorded by the cast of a production that opened last

January in New York. The show is set on three consecutive Saturday nights in

1929. On the first night, a group of male friends in their early 20s share

their frustration at not having dates.

(Soundbite of music from "Saturday Night")

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) So what can you do on a Saturday night alone?

Unidentified Man #2: (Singing) Who needs a view on a Saturday night alone?

Unidentified Man #3: (Singing) If it's a Saturday night and you are single,

you sit with a paper and fight the urge to mingle.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) And home is a place where you got to go back

alone.

Unidentified Man #3: (Singing) Home is a place where the future looks black

alone.

Unidentified Man #2: (Singing) I like The Sunday Times all right, but not in

bed.

Unidentified Men: (Singing in unison) Alive and alone on Saturday night is

dead.

Unidentified Man #1: You know...

Unidentified Man #3: Will you knock it off already?

Unidentified Man #2: Oh, give it a rest.

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Man #1: Here's a revival of "Ben Hur" goes in at 9:15 at the

Cushman.

Unidentified Man #2: So when I got my mind on sex, who gives a damn for

Francis X. Cushman(ph)?

Unidentified Men: (In unison) The moon's like an overloaded marquee sign, it

shines at you friendly and bright. I got my buddies and my buddies are fine,

but not on a Saturday night.

Unidentified Man #2: Johnny Mack Brown and Bessie Love...

Unidentified Man #1: Love...

Unidentified Man #2: ...Love...

Unidentified Man #1: ...Love...

Unidentified Man #2: ...Love...

GROSS: "Saturday Night" never made it to Broadway in the '50s because the

producer, Lemuel Ayers, died after a few backers' auditions were held. I

asked Stephen Sondheim if he had to perform his songs at the auditions.

Mr. STEPHEN SONDHEIM: I performed at the first one. I did the whole score by

myself. We didn't raise one cent. And the producer, Lem Ayers, was so

discouraged, he almost dropped the show, but he said, `Why don't we get a

professional cast, and you just play the piano and let professionals sing it?'

And I said, `Fine.' And so we did, and we had quite a sterling cast: Jack

Cassidy to play Gene, the lead, and Alice Ghostley to play Celeste, and Artie

Johnson to play Bobby, a girl named Leila Martin to play the female lead,

Helen. And Jay Harnick, Sheldon Harnick's brother, was one of the cast. And

we did, I guess, four auditions and raised about a quarter of the money. And

then Artie left and was replaced by Joel Grey. And we did four more auditions

and raised about half the money, and then that's when Lem died.

GROSS: I know that you hate to perform. Was it an awful position to have to

do the first backers' audition?

Mr. SONDHEIM: No. It was nervous-making. But, you know, I was proud of what

I'd written, and I wanted to show off. So it was fun, although very

nervous-making. I was very discouraged when it didn't raise any money, but,

you know, it was a good lesson because it was the first time people started to

sort of sneer at me. And all young composers go through this where, you know,

you're condescended to or looked down on because nobody's ever heard of you.

And it was a kind of an annealing process, and it was helped a lot--or my hurt

was helped a lot when I got professionals, like Jack and Leila and Alice, in

to do the auditions from then on, because the whole show then took on a kind

of professional sheen, and the audiences were a little less condescending.

GROSS: When the producer of the show died of leukemia and the show didn't

make it to Broadway because of that, how did you deal with the disappointment?

I mean, was that something that was really crushing, or did you feel, `Well,

you know, I'll just go on and have another opportunity'?

Mr. SONDHEIM: I don't honestly remember. I don't remember being supremely

crushed, and I think it's because probably I had the hope that somebody else

would pick it up or that Shirley, Lem's widow, would be able to get it on. I

think she was trying to get a co-producer. So the show wasn't dead, per se,

just because the producer was, at least in my head. I guess that's what

happened, and it was that very same year that I got the job of writing "West

Side Story." So, you know, I was quickly at work again on something new,

which is, you know, the best kind of healing for such a situation.

GROSS: I really like the singing on the new CD of "Saturday Night." And

I'm...

Mr. SONDHEIM: Oh, me, too.

GROSS: ...wondering if you think it's difficult to find good Broadway singers

now. It sometimes strikes me as a form of singing that's almost dying out, I

think, in part, because most people don't grow up listening to Broadway

singing; they grow up listening to pop or rock, hip-hop. And it's just a

different approach to singing.

Mr. SONDHEIM: You're absolutely right. When people come in to audition, we

often have to ask, particularly younger people, to just sing the song straight

instead of stylizing them, instead of bending the notes, instead of doing the

kinds of styles you're talking about. They tend to sing mostly very loud and

all at one level of expression, which is pretty boring on a stage and fine for

a concert. And, also, it's inhuman; that is to say, it has nothing to do with

characters since they stylize so much when they sing that the character is

lost.

So we often have to ask them, please, to sing it straight, meaning--and for

some of them, that's very hard to do. They can't just sing the notes, they

can only fool around with the notes. And a lot of them have a faulty sense of

pitch, and it's revealed when they have to sing the songs straight. But since

most Broadway shows require a much more straightforward kind of vocal sound

and vocal production and vocal style than pop and rock, you're absolutely

right, it's harder to find them. On the other hand, there are plenty of good

voices and a lot of good talent around.

GROSS: Did you find that there are certain intervals that you have in your

songs or anything else that gives singers a lot of trouble, that they're not

used to it?

Mr. SONDHEIM: No. No. I hear second-hand complaints my songs are difficult

to sing, but very few firsthand complaints from people who actually sing them.

I think what happens is that I write a lot of dissonance in the

accompaniments, and though it's mild dissonance, it's still dissonance. And

there will be a chord or a line of counterpoint in the music that will clash

directly with the note being sung, and a lot of people have trouble hearing

the note they're supposed to sing when the chord that's being played or the

contrapuntal line that's being played clashes. There's never any problem with

a trained singer, but with untrained singers, that often happens.

On the other hand, once they get used to it and see the reason I've chosen

those notes, which often has to do with inflection and sometimes with harmonic

resolution, the difficulties usually melt away. The people who have

difficulty when they're in rehearsal usually have difficulty with lyrics,

particularly with some of the faster lyrics I write and some the patter

lyrics. And if I see that the singer's in difficulty, sometimes it's my

fault, and I will take a word out or change a phrase to make it easier on the

teeth and the tongue or the lungs.

GROSS: Well, a good example of that patter song is "Not Getting Married,"

which is maybe one of the wordiest songs ever written. It's amazing somebody

could do it.

Mr. SONDHEIM: It's wordy but it's not hard to sing. And what's hard is the

melody because the melody is comprised mainly of half steps. And unless the

voice and the ear are good, the singer gets into a kind of schpreshdom(ph), a

kind of semi-talking. But the patter itself is written pretty carefully. The

last section I think there are some breathing problems. That's a lyric I

should improve, but most of it sings very well. And what most singers don't

understand is that the faster you sing it, the easier it is.

GROSS: Why is that?

Mr. SONDHEIM: Well, because less breathe is required. And when people

sing it slower, they tend to punch certain of the heavy consonants like P's

and B's and expend breathe that should be better preserved for finishing the

phrase in one breathe. If you listen to Veanne Cox singing "Getting Married

Today" on the recording of the show that was done by the Roundabout Theatre in

New York, you'll hear absolutely split-second timing and she sings it faster

than I guess anybody else has ever sung it. And you get every word, and she

has no trouble at all.

GROSS: Why don't we hear it. Here it is.

Ms. VEANNE COX: (Singing) Listen, everybody, look, I don't know what you're

waiting for. A wedding was a wedding is a prehistoric ritual where everybody

promises fidelity forever which is maybe the most horrifying word I ever heard

which is followed by a honeymoon where suddenly you realize you're saddled

with a nut and want to kill me but you shouldn't. Listen, thanks very much,

but I'm not getting married. Go have lunch because I'm not getting married.

You've been grand, but I'm not getting married. Don't just stand there, I'm

not getting married. And don't tell Paul, but I'm not getting married today.

So can't you go. Why is nobody listening? Goodbye. Go and cry at another

person's wake. If you're quick for a kick and you could pick up a christening

but please on my knees there's a human life at stake.

Listen, everybody, I'm afraid you didn't hear. Do you want to see a crazy

lady fall apart in front of you. It isn't only Paul. I may be ruining his

life and both of us may be losing our identities. I telephoned my analyst

about it and he said to see him Monday, but by Monday I'll be floating in the

Hudson with the carnage. I'm not well, so I'm not getting married. You've

been swell, but I'm not getting married. Clear the halls, 'cause I'm not

getting married. Thank you, all, but I'm not getting married. And don't tell

Paul, but I'm not getting married today.

GROSS: We'll hear more from Stephen Sondheim after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Stephen Sondheim. There's a new cast recording of his

first musical "Saturday Night." It was written in the mid-'50s but wasn't

staged until 1997.

Your mentor was Oscar Hammerstein. And I've read several young composers

quoted as saying that you were their mentor. I'm not sure whether that meant

on a more conceptual level that your records mentored them or whether you

personally mentored them. But what's some of the advice you've most often

given to young composers?

Mr. SONDHEIM: Oh, I don't give advice. I talk about the specifics at hand.

I rarely deal in generalizations. I have sort of three principles of writing

which are all classical principles that have been applied to art throughout

many--well, some of them have only been articulated in the 20th century, but

less is more and content dictates form. And those are two principles. And

the third one, I guess, would be God is in the details. And I think in terms

of lyric writing, I know that clarity is the most important principle:

clarity of thought, clarity of words, clarity for the singer, clarity of

intention. But I think that those three principles will serve any art form

and particularly songwriting.

GROSS: Well, let's talk a little bit about content dictates form. I know you

really like to look closely at the book of a play and sometimes even take

lines from it and use that in a song. Talk a little bit more about how

content suggests what the lyric and what the music should be like.

Mr. SONDHEIM: Well, I mean, it's obvious if you take, let's say, the content

of--oh, I don't know, let's say the content of "Company." It dictates the

style and the form of the songs. The content is about urban living and about

what used to be called relationships and there's a kind of nervous energy in

the script. It's impossible to talk about these things without...

GROSS: A specific...

Mr. SONDHEIM: ...referring to the script, I mean, because it's the librettos

that give rise to all these principles--what the characters are, what the

author's style is. The style of "Sweeney Todd" is obviously quite different

than style of "Company," and therefore, the content, in other words, what it's

about, one is about revenge, the other's about, as I say, relationships,

dictates kind of the semi-operatic or operetta forms that are used in "Sweeney

Todd" as opposed to the absolute musical comedy forms that are used in

"Company." It's what arises from the content of the libretto, and then the

specifics of the situation and the song that dictate form and style, too.

GROSS: How about a song like "What More Do I Need?" which is a song from

"Saturday Night"?

Mr. SONDHEIM: Oh, "What More Do I Need?"--first of all, it was added after

Lemuel died.

GROSS: Oh, OK. Right.

Mr. SONDHEIM: But there again--all right, sure. "Saturday Night" is a

standard '50s music comedy. It's lighthearted and light in--the content is

that of musical comedy. What it's about namely--you know, about the market

and about a fellow whose values are wrong, etc., etc., is much less important

than the general style of libretto. The libretto is wisecracks, swift

character drawing. It was kind of standard, light playwriting, what they used

to call light comedies, of the '30s, '40s and into the '50s before the '60s

revolution in playwriting. And so the music--I hope the songs--mirror that,

imitate it. They're 32-bar songs. They're standard forms the way the play is

a standard form.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear "What More Do I Need?" I think this has a

really great lyric and a really catchy melody. This is from the new cast

recording of "Saturday Night."

(Soundbite of recording from "Saturday Night")

Unidentified Man: (Singing) Once I hated this city. Now it can't get me

down. Slushy, humid and gritty, what a pretty town. What? But I could be

duller, more depressing, risque. Now my favorite color is gray. Oh, wall of

rain as it turns to sleet, a rack of sun on a one-way street. I love the grim

all the time and what more do I need? My window pane has a lovely view, an

inch of sky and a fly or two. Why, I can't see half a tree and what more do I

need.

Unidentified Woman: (Singing) The dust is thick and it's calling. It simply

can't be excused. In winter even the falling snow looks used.

Unidentified Man: (Singing) My window pane may not give much light. But I

see you, so the view is right. If I can love you, I'll pay the dirt no heed

with your love, what more do I need? Someone shouting for quiet...

GROSS: This is the song from the new cast recording of Stephen Sondheim's

musical "Saturday Night."

The musical theater is becoming more and more devoted to repertory and several

of your shows have had, I'm glad to say, new productions. What do you think

of that trend? I mean, it's been great for your shows 'cause it's enabled us

to go see them again or see them for the first time if we missed them the

first time around. And it's, I think, been particularly good 'cause some

musicals like "Merrily We Roll Along," which didn't stay on Broadway for long,

the new productions have been a great opportunity to actually see it. But,

you know, in the larger scheme of things, what do you think of the emphasis

now on revivals?

Mr. SONDHEIM: Oh, it's deplorable because young writers aren't getting a

chance to get their work heard, at least on Broadway, but that's been going on

for years. It isn't just the revivals. Producers, because musicals are so

expensive, are very unwilling to take chances on unknown writers unless the

project that they're writing for is a presold project, meaning a hit movie

or...

GROSS: Like "The Lion King" or something.

Mr. SONDHEIM: Yeah, exactly or "The Full Monty" that's coming along which is

a writer new to Broadway. And I doubt if he had written a show, the title of

which nobody had ever heard of that he would have gotten a chance. Producers

just are unwilling. I can understand why, 'cause musicals are so expensive to

put on. But it's terrible because the only way you learn to write is by

writing a show and writing songs and having the show put on and then writing

another one and putting it on and writing another one and putting it on.

That's the only way you learn, and you get better through experience, not

through theory. And even the writers who manage to get a show on don't get

another show on for years afterwards. And so they improve themselves very

slowly, if they get a chance at all. That's what's terrible about it.

GROSS: Stephen Sondheim, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. SONDHEIM: OK.

GROSS: And I wish you good luck with your musical "Wise Guys" when it opens

in a few months.

Mr. SONDHEIM: Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: The new recording of Stephen Sondheim's first musical, "Saturday

Night," features the cast of New York production, which opened last January.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR. Here's another song from "Saturday

Night."

Unidentified Woman: (Singing) So many people in the world and what can they

do? They'll never know love like my love for you. So many people laugh at

what they don't know. Well, that's their concern. If just a few, say half a

million or so, could see us, they'd learn. So many people in the world don't

know what they've missed. They'd never believe such joy could exist. And if

they tell us it's a thing we'll outgrow, as jealous as they can be, that with

so many people in the world you love me.

Unidentified Man: (Singing) So many people in the world don't know what

they...

(Credits)

GROSS: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Greg Kinnear on his new movie "Nurse Betty," his

career and his childhood experience in Beirut

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Greg Kinnear, stars with Renee Zellweger, Morgan Freeman and Chris

Rock in the new comedy "Nurse Betty." When Kinnear made his acting debut in

the 1995 film "Sabrina," there were a lot of skeptics. Who was this guy? His

only credentials were hosting the late-night talk show "Later" and "Talk

Soup," E! TV's comic wrap-up of the most absurd moments of the day's TV talk

shows. But soon after Kinnear started acting, he was nominated for an Academy

Award for his supporting role in the film "As Good As It Gets."

In "Nurse Betty," Renee Zellweger plays Betty, a lovely, naive woman married

to a lying, obnoxious, used-car dealer who secretly sells drugs. She

accidentally witnesses the gruesome murder of her husband by two hit men.

She's so traumatized that she has a breakdown. She confuses her favorite soap

opera with reality and believes that she is the lost love of the soap opera's

main character, the brilliant surgeon, Dr. David Ravell. The soap opera star

is played by Greg Kinnear. Here he is in a scene from the soap talking with

one of the nurses.

(Soundbite from "Nurse Betty")

Ms. SUNG HI LEE: ("Jasmine") You know, you can't keep going like this, David.

It's not good for you or anybody else.

Mr. GREG KINNEAR: ("Dr. David Ravell") Do I have a choice, Jasmine?

Ms. LEE: You know you do. Sometimes it seems that you're...

Mr. KINNEAR: What?

Ms. LEE: ...running away from something.

Mr. KINNEAR: I'm not running from anything. I'm trying to live with it, with

the moment, and it won't leave me alone. Why did I let her go by herself that

night? Why did I have to play racquetball with Lonnie? She'd still be here if

it weren't for that.

Ms. LEE: Now you listen to me, no matter how many procedures you take on,

it's not going to bring her back.

Mr. KINNEAR: I know that, or at least I thought I did. Lately I just feel

so disconnected. The only time I really feel alive is when I'm working on a

patient. Then I can forget.

Ms. LEE: And the rest of the time?

Mr. KINNEAR: You ever feel like something really special's about to happen

to you, Jasmine? You don't know what it is or where it'll come from, but you

know that it's coming.

GROSS: Greg Kinnear, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. KINNEAR: Well, thank you for having me.

GROSS: In this movie, you play an actor who plays a doctor in a soap opera.

So in those soap opera episodes, when you're the doctor, do you play the

doctor differently as this actor being the doctor than you would as Greg

Kinnear playing a doctor?

Mr. KINNEAR: I certainly hope so.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. KINNEAR: I think the character I play--you know, the actor George

McCord, in this particular movie, is not necessarily a great actor. I don't

think he's necessarily mastered much in the way of subtlety in terms of his

performance ability. And I would hope to perhaps underplay some of the

emoting that...

GROSS: Yes.

Mr. KINNEAR: ...he tends to take to the nth degree. But, you know, there is

a--in fairness, too, we have some fun with, you know, the soap opera element

in this movie. But in fairness to actors that are on these shows, you know,

I've worked with, you know, some amazing actors who come from soap operas,

including Meg Ryan, and Morgan Freeman was on a soap opera for a few years.

And there are a lot of great actors in soap operas right now who, undoubtedly,

are going to be big film stars down the line.

I think the reason they kind of get the rap that they do as `soap stars' is

just the context with which they have to work. I mean, there's an enormous

amount of technical detail involved in what these people do. I went down to

"General Hospital" for a couple of days and watched this, and it's so specific

in terms of the marks that they have to hit, the huge amount of pages that

they have to cover in a single day. We do maybe a page, maybe two pages a day

in movies. They do about 35, 40.

And, of course, lastly, they have to say this preposterous dialogue that must

fall from their mouths, somewhat not so gracefully, and all of it has to, you

know, be kind of oversold because it's a show that comes on in the middle of

the day when a lot of people are kind of working, kind of half-watching the

television, one eye on it. So the big looks, the big music, the big vocal

exchanges and the lines all sort of create this little bit of comic element to

a soap opera. But I don't think it's necessarily bad actors. Again, that

being said, I don't think the actor I play in this movie is a particularly

good one.

GROSS: What are some of your favorite lines from the soap opera that you had

to not only do, but overdo?

Mr. KINNEAR: `I just know that there's something special out there for me

somewhere.' I don't know--there were a series of great lines. Some of these

were penned by the original screenwriters, you know, John Richards and James

Flamberg. And Neil LeBute, who was our great director in this movie, also

wrote a series of pages for the soap opera so that as you watch the movie, the

soap opera story plays out kind of on the sidelines of this film. So you're

seeing a movie and, within the movie, a soap opera story that is being closely

watched by all the real-life characters in the movie.

GROSS: What are the secrets to bad acting? What are the secrets to playing

an actor who's a bad actor?

Mr. KINNEAR: I just think it's...

GROSS: Timing. Timing's everything.

Mr. KINNEAR: Yeah. I guess timing or something. It was just like, you

know--for me, I think it's saying things at the wrong pitch, at the wrong

volume, at the wrong time with the wrong kind of--I mean, anything that didn't

feel organic was absolutely right on for certainly what we were going for.

And, you know, at the same time, you know, we were trying to not really send

up soap operas or spoof them, because that would have distracted from our main

story in the movie, but we were certainly trying to exploit a little bit what

that world is and have some fun with it.

GROSS: Now we're talking about playing a not-very-good actor. You didn't go

to, like, acting school and everything. You really kind of stumbled into

acting in a way after being on TV. You got a really good part in "Sabrina."

And then in one of your early movies--you know, 1997, this is your second

really big part in "As Good As It Gets." You started with Jack Nicholson.

You won a National Board of Review's best supporting actor award, nomination

for an Academy Award, and that's all pretty good for, you know, early acting

career for somebody who didn't even study acting. What was it like for you to

get started in movies without that kind of background?

Mr. KINNEAR: You know, it was very scary and very intimidating. My first,

you know, experience was, you know, "Sabrina" with Sydney Pollack directing,

and Harrison Ford was in it, like you said. And it was, you know, a bit

overwhelming. I certainly tried to, you know, not bring any sense of

confidence lacking or moping around the set. I tried to act like, `Yeah,

sure, I belong here. I know what I'm doing here.'

But, you know, to be sure, I was definitely a little overwhelmed by the

circumstances. But I had, in Sydney, a great director and somebody who walked

me through the process and kind of, you know, helped me find my way through

all of this. And it's been something that I've tried to employ since then. I

really do believe that the director, although not always successful in

realizing the outcome of the movie, is your best bet as an actor. They're the

person who will most challenge you and most help you solve the problems of who

your character is and finding a performance that's hopefully interesting.

GROSS: My guest is Greg Kinnear. He's one of the stars of the new film

"Nurse Betty." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Greg Kinnear's my guest, and he's starring in the new movie "Nurse

Betty."

When you were a kid, your father was a diplomat with the State Department, so

the family lived overseas for a while. And you moved to Beirut, I believe,

just before the civil war and were there during part of the civil war. Did

your father not realize what you'd all be getting into? What year was this?

Mr. KINNEAR: This was 1975. When we went over there earlier in the year, you

know, the civil war had not broken out. There was certainly some tensions

building up there, and, you know, the Muslim and Christian factions were

beginning to--their relationship, which was kind of loosely structured to

begin with, was sort of falling apart, but it wasn't listed as like a danger

zone on their, you know, State Department warning thing that they put out or

anything like that. So this was his assignment, and I remember them, you

know, pulling all of us kids together and saying, `Hey, we're going to

Lebanon.' So it sounded interesting, and I don't think that, at the time we

went over there, there was any real scare. It was only after we got there

that the war broke out.

GROSS: What are some of the things that you witnessed in the fighting when

you were there?

Mr. KINNEAR: Less things that I witnessed and more things that I heard, which

was, you know, primarily just gunfire and an enormous amount of, you know,

gunfire and shelling. They were shelling the city when we left in the last

week there. I crossed the street one day to go see a friend, and I saw--you

know, there was always a couple of people selling apples and stuff from their

carts. And I crossed the street one day and noticed that everyone suddenly

was not tending their various fruit carts and realized there were two groups

of guys coming down from opposite ends of the street armed, and they started

firing. And, you know, I ran across the street, went to my friend's house and

kind of waited it out while that happened.

But, you know, that was pretty exciting. But, you know, I was 12 years old.

It was like that John Boorman film "Hope and Glory," where you're just kind of

watching it all with wondrous eyes.

GROSS: So you weren't traumatized?

Mr. KINNEAR: Oh, yes, I was traumatized. Maybe wondrous eyes is the wrong

word. No, I was--you know, how it affected me, I don't know. I don't have

any other experience to compare it with. I don't like loud noises to this

day; maybe that's some sort of residual effect of that. I don't like gun

battles that I'm in the middle of, I know, so yeah, I guess maybe it did have

some sort of effect on me.

GROSS: It must have been so confusing to be in a different culture with a

different language, and everybody around you is fighting.

Mr. KINNEAR: Yeah. You know, the Lebanese people are wonderful, wonderful

people. They really--it was a tragedy what happened there, and I'm not sure

it was really avoidable. It was very sad to watch because, you know, our

family had many friends who were Lebanese who certainly were going to stay

behind after we were evacuated. And the hope, I think, for everybody there,

and even after we left, was that this would be a short-lived conflict. And I

just never imagined it dragging on for, you know, the 15 or 18 years that it

did.

But while we were there--when we arrived, it was beautiful, it was wonderful,

and all those cliches of Beirut being the Paris of the Middle East is

absolutely true. It was a gorgeous city and full of, you know, life and color

and these great-spirited people. And what happened in that short time, when

things started to break down, was awful to watch.

GROSS: My guest is Greg Kinnear, and he's one of the stars of the new movie

"Nurse Betty."

Let's talk a little bit about the "Talk Soup" era. Why don't you describe the

show for our listeners who haven't seen it.

Mr. KINNEAR: It's a half-hour program. It's very loose in its format and,

you know, had very little scripted, and it was looking at the highlights of

the daytime talk shows, which, at the time, were just being discovered, I

think. You know, it's very commonplace to talk about cross-dressing

transsexuals now around the dinner table, but back then, "Jerry Springer" was

just being born and unleashed, as was, you know, "Geraldo" and, you know,

"Richard Bey" and, you know, "Jenny Jones" and "Montel" and some of these

other programs that were doing that kind of outrageous programming at the

time.

And our show would take the highlight of, you know, nine to 12 different shows

and put them together in this half-hour, kind of wacky format. And people

started catching on to it in the evening as they watched it, and it grew. And

yet, you know, it was on E!, which was not in that many homes at the time, I

mean, by television standards, and I've always been kind of baffled at

people's awareness of it and how they discovered it, because it certainly was

on E! a lot, but at the time E! wasn't really in much of the public

consciousness.

GROSS: Let's hear a clip from "Talk Soup," and this is from a 1994 edition of

the show. Here's Greg Kinnear.

(Soundbite of "Talk Soup" theme music)

Mr. KINNEAR: If you don't mind. We're back. You're watching "Talk Soup."

We're continuing now. This highlight from the "Richard Bey Show" tests the

laws of gravity and the bounds of good taste. You're about to meet an

impressionably endowed stripper who goes by the name Candy Apples.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. KINNEAR: She'll be going chest to chest with a more modestly proportioned

young lady, who we'll simply call Miss Jersey.

GROSS: That's Greg Kinnear from the "Talk Soup." What was it like for you to

watch all of--did you actually sit down and watch all of these shows, or did

your producers just bring you clips to watch so that you could dish the clips?

Mr. KINNEAR: Well, I had, I don't know, like the little mental timer built

into my head telling me to be late to the studio. We would be kicked out at

the same time every single day, and I would just be lingering around my

apartment as late as I could possibly be so that when I got there, it was just

whirlwind insanity. I was not one of the viewers. We had about five

screeners, these poor souls, who would sit around for hours and hours and

hours--and I'm going to say it one more time--and hours, and watch highlights

of daytime talk shows. And after they had watched the hour, they would go

find the most potent 60 seconds that they could, the nectar if you will.

And they would take that, and they would have these, you know, kind of all set

up in the control room. And, you know, after we watched maybe, you know, 13

or 14 of them--we only could fit about nine or 10 on the show, and I'd select

the nine or 10 we were going to use. And then I'd run into the studio. You

know, we'd slap on some, you know, clothes and we'd figure out a couple of

gags we could do with the material that we had. And then we just kind of let

her go. And we tried to do it, basically, you know, live. We would stop down

sometimes because of technical problems, but, generally, the idea was to just

keep it going and keep it kind of feeling, you know, very edgy. And we really

felt like we could do anything because we--when the show came on, for the

first year and a half, I don't even think the network knew it was on the air.

GROSS: My guest is Greg Kinnear. He's one of the stars of the new film

"Nurse Betty." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with Greg Kinnear. He's now starring

in the film "Nurse Betty."

Let me play a clip from your 1997 movie "As Good As It Gets." And you played

an artist who was gay. Jack Nicholson played your homophobic next-door

neighbor, who's also a writer and an obsessive-compulsive. Early in the film,

your studio is robbed and you're badly beaten. And in this scene that we're

going to hear, you're in a wheelchair. You've just found out that you're also

completely broke, and you have nobody to help you. But Nicholson has at least

been helping out a little bit by walking your dog, even though he hates dogs.

Here's the scene.

(Soundbite from "As Good As It Gets")

Mr. KINNEAR ("Simon"): Thank you for walking him.

(Soundbite of dog barking)

Mr. KINNEAR: If you'll excuse me, I'm not feeling so well.

Mr. JACK NICHOLSON ("Melvin"): Eww, this place smells like (censored).

Mr. KINNEAR: Go away.

Mr. NICHOLSON: This--this cleaning lady doesn't...

Mr. KINNEAR: Please just leave!

Mr. NICHOLSON: What happened to your queer party friends?

Mr. KINNEAR: Get out of here! Nothing worse than having to feel this way in

front of you.

Mr. NICHOLSON: Nellie, you're a disgrace to depression.

(Soundbite of door opening)

Mr. KINNEAR: Rot in hell, Melvin.

Mr. NICHOLSON: No need to stop being a lady. Quit worrying. You'll be back

on your knees in no time.

(Soundbite of scuffle and dog barking)

Mr. KINNEAR: Is this fun for you? Hmm? You lucky devil, it just keeps

getting better and better, doesn't it? I'm losing my apartment, Melvin, and

Frank, he wants me to beg my parents, who haven't called me, for help, and I

won't. And I--I don't want to paint anymore. So the life that I was trying

for is over. The life that I had is gone, and I'm feeling so damned sorry for

myself that it's difficult to breathe. It's high times for you, isn't it,

Melvin? `The gay neighbor is terrified.' Terrified!

GROSS: That's Greg Kinnear with Jack Nicholson in a scene from "As Good As It

Gets."

Tell me how you decided to play this character, this artist who is gay--how

weak and how strong, how serious and how funny. Because the character's a mix

of that. There's scenes where he's really weak, scenes where he's strong,

scenes where he's really sad or serious and scenes where he's very funny.

Mr. KINNEAR: Mm-hmm. Well, I've always--you know, when I first read the

script, I was just amazed at the potential of what that character could be.

And to me, he seemed to have many things, you know, materialistically and a

certain amount of that kind of those unstable friendships, those shell

associations that we have around us sometimes, who they're there for you, but

they're not really there for you. And he had a lot of those types of things

that weren't built on very solid ground initially in the movie. And, of

course, he goes through that beating.

And I think he really loses everything. He loses everything. He loses all of

those things around him and even his own sense of worth and his own sense of

who he is. And for him, the journey is rediscovering what those things are.

And his having done that, through the help of this odd waitress, complete

stranger in his life, and this, you know, what he calls horrible, you know,

beast of a human being, or whatever the quote is, are the things that actually

help him find what it is that he really is. And I think that, you know, he's

better off. He's not going to need probably any of the things that he did at

the beginning of the story line.

So that's, you know, a great arc for any character, and it's, you know--what I

look for in scripts is: Is there some sort of journey here? Is there some

line? And some movies provide the opportunity to do that, some don't. But

the ones that do, the ones that allow for some sort of circle to take place or

some sort of emotional journey, either up or down, are what's most interesting

to me.

GROSS: You know, after doing daily shows for years, what's it like to do

movies where you're working really intensively for a few weeks or a few

months, then there may be a stretch where there's nothing until your next

movie?

Mr. KINNEAR: Hardest thing I've had to deal with, hardest thing. The rhythms

of having a real job or a daily experience, where you go in and you are, you

know, heading back to work every single day and, you know, working in this

kind of family environment was just such a different energy than movies, which

are nothing in between jobs--nothing. And then when you get one, an intense

amount of work that's very sporadic. It's throughout the day. You're up,

you're down, you're up, you're down. And it's just an odd little graph of

insanity mixed with lulls like you can't believe. And that's been very

difficult for me, as well as the idea of you're doing a movie and now you're

not doing a movie. And you've got to wait until you find the right script,

and, `Is this the right script?' And, `Is that the right movie?' And if it's

not, you may wait a little bit longer. And how much longer will you wait? So

it's a very strange, little game that's hard to adapt to.

GROSS: Well, Greg Kinnear, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. KINNEAR: Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: Greg Kinnear is currently starring in the film "Nurse Betty."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross. We'll close with a 1965 recording by tenor

saxophonist Stanley Turrentine. He had a stroke on Sunday and died Tuesday.

He was 66.

(Soundbite of recording with Stanley Turrentine)

GROSS: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.